Ancient paintings and calligraphy have survived countless wars and calamities, which is a great fortune. We have a sense of awe when we face them, and printing on them without making any mistakes is certainly a challenge.

More than 20 years ago, renowned art historian Bai Qianshen was commissioned to affix his collector's seal to the collection of Bada Shanren and other extant paintings and calligraphies in the collection of collector Wang Fangyu. He recently wrote an article recalling this event. This article is published with Bai Qianshen's authorization.

My first encounter with seals was in 1973. It wasn't because of calligraphy or painting, but because my work required the use of my name seal. I graduated from middle school in 1972, during the latter half of the Cultural Revolution. That year, Shanghai didn't recruit high school students, and middle school graduates faced job assignments. My older brother had been sent to the countryside in Heilongjiang in 1969, and according to policy, I could stay in the city to work. I chose to study finance at the Shanghai Finance and Trade School, a two-year program, but in my second year, we started interning at a bank. We worked at the teller's counter in the savings office, serving customers' deposits and withdrawals. After calculating the accounts, I had to stamp my name seal on the customers' passbooks and the bank's ledgers. The seal was a standardized one for all interns, a flat, horizontal seal in regular script carved on a cow horn. From my bank internship in the winter of 1973 until I entered university in the autumn of 1978, I worked at the bank for five years. You can imagine how many times I used that seal. However, it had no connection to calligraphy or painting.

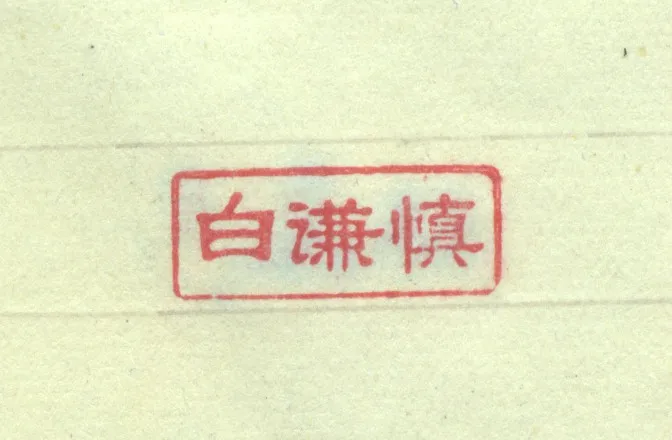

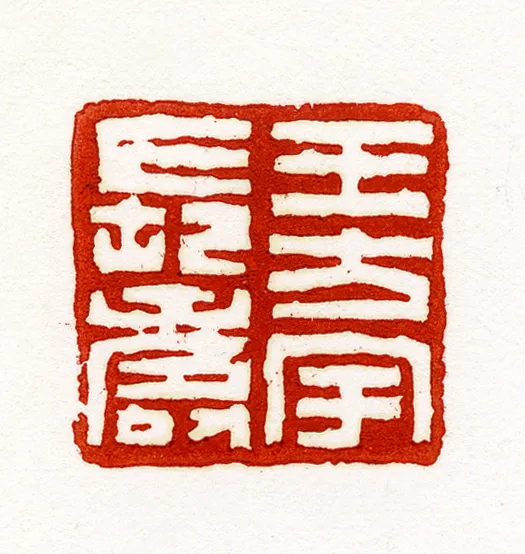

The seal used by Bai Qianshen when he worked at a bank in the 1970s

In 1973, I began learning calligraphy under the guidance of Mr. Xiao Tie. At that time, entertainment was scarce, and after developing a liking for calligraphy, it became an important part of my leisure time. Besides practicing the *Duobao Pagoda Stele*, I would buy some calligraphy publications that seem quite rudimentary today for reference, visit exhibitions, and study the works of others. Seeing people stamping their calligraphy and paintings with seals, I also asked a friend of Mr. Xiao Tie, surnamed Wang, to carve two seals for me. I began to imitate the ancients and my teachers and friends, stamping my name seal on my immature works. More than fifty years have passed, and the habit of stamping my seal on my writing has remained unchanged.

The use of seals predates that of China in some civilizations. Early Mesopotamian civilizations used cylinder seals. Ancient Indus Valley civilization, now part of Pakistan, also had seals with inscriptions and images. The exact date of seal use in China is still debated among scholars. Some believe seals appeared and were used before the late Shang Dynasty. Seals as credentials were already quite common during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. From then on, the use of seals in China has never ceased, becoming another example of the enduring continuity of Chinese culture. In the time of Wang Xizhi, the Sage of Calligraphy, skilled calligraphers did not affix their seals after writing. The use of seals on paintings and calligraphy may have initially stemmed from collecting activities. Zhang Yanyuan's *Record of Famous Paintings Through the Ages* records collector's seals. By the Song Dynasty, a small number of literati began to affix their seals after signing their works, a practice known as "signature seal." By the Yuan Dynasty, using signature seals gradually became a common practice, although a few calligraphers and painters still sometimes did not use their seals.

In 1990, I entered the field of art history. Since then, I've had more opportunities to handle ancient artifacts, and I often see the seals of collectors, both past and present, on ancient paintings and calligraphy. The senior Chinese collectors I've met, such as Wang Jiqian, Wang Fangyu, and Weng Wange, all affixed their seals to their collections to indicate that these works had once been in their possession. This practice of using collector's seals also influenced Western collectors of Chinese paintings and calligraphy. On the collection of ancient Chinese paintings and calligraphy by John Crawford, one can see seals bearing the inscriptions "Gu Luofu" and "Han Guang Ge" (Gu's studio name). Robert Ellsworth also frequently affixed his seal "An Siyuan" to his collection of Chinese paintings, calligraphy, and rare rubbings. John Elliott, an alumnus of Princeton University, possessed one of the most extensive collections of ancient Chinese calligraphy in the West, including renowned works such as a Tang Dynasty copy of Wang Xizhi's *Xingrang Tie* and Huang Tingjian's *Zeng Zhang Datong Juan*. His close friend, Ms. Liu Xian (Mrs. Luo Jimei), once asked me to carve a red seal for him. However, Eliot never affixed his seal to his collection of ancient paintings and calligraphy until his death. After his death, his collection of paintings and calligraphy was collected by the Princeton University Art Museum according to his will, and these paintings and calligraphy will never bear his collector's seal.

The inscriptions and collector's seals on ancient paintings and calligraphy have provided numerous research clues for later art historians. My first large-scale, close-up examination and organization of inscriptions and seals on ancient paintings and calligraphy occurred in the early 1990s. In 1992, my teacher, Professor Ban Zonghua, was commissioned by the Yale University Art Museum to curate an exhibition of fine Ming and Qing dynasty paintings and calligraphy from the Wang Nanping family collection. My classmates and I participated in the exhibition's preparation. Professor Ban and his students visited Professor Wang Puren, the son of Mr. Wang Nanping, to select works. After the works were chosen, they were transported to the Yale University Art Museum, where we began studying the collection. Professor Ban invited some senior scholars to write papers, while we wrote entries for the exhibits and created catalogues. Cataloging involved recording the dimensions, materials, labels, introductory sections, inscriptions, seals, etc., of each work in writing and publishing them in the catalogue. Because I could carve seals and identify cursive and seal script, I was primarily responsible for the catalogue work. The entries and records we compiled were later published in the exhibition catalogue "Selected Ming and Qing Dynasty Paintings and Calligraphy from the Yu Zhai Collection," published in 1994. That work of compiling the materials was of great help to my later research. After I became a professor, I often trained my students in this area. Nowadays, there are not many courses in universities that teach this kind of knowledge, and not many young students are proficient in using inscriptions and seals.

Most scholars who study ancient Chinese painting and calligraphy are not collectors. Although they can see many ancient paintings and calligraphy in various exhibitions, warehouses, catalogs, and online, few have the opportunity to write inscriptions or stamps on them. However, due to a special opportunity, I stamped a batch of precious ancient paintings and calligraphy within two days. This happened in 1998 and was related to the collection of Mr. Wang Fangyu (1912-1997).

two

Mr. Wang Fangyu was a native of Beijing, from a wealthy family of merchants. He loved art from a young age, and his interest in collecting likely developed in the 1940s, as evidenced by a seal carved for him by Qi Baishi among his collection. After World War II, he studied in the United States, and after graduating, taught at Yale University and Seton Hall University, becoming a renowned expert in Chinese language teaching. Unlike typical professors, Mr. Wang was very business-minded; in addition to teaching, he also dealt in rare books. He had a deep friendship with Zhang Daqian, and in the 1950s, after purchasing some of Bada Shanren's works from Zhang on installment payments, he scrimped and saved, using his expertise to buy paintings and calligraphy at auctions, gradually building the world's largest private collection of Bada Shanren's works. Besides Bada Shanren, he also collected works by Qi Baishi, Fu Baoshi, and other modern and contemporary painters and calligraphers.

Wang Fangyu and Bai Qianshen attended a Chinese seal engraving seminar at the China Institute in New York in 1992.

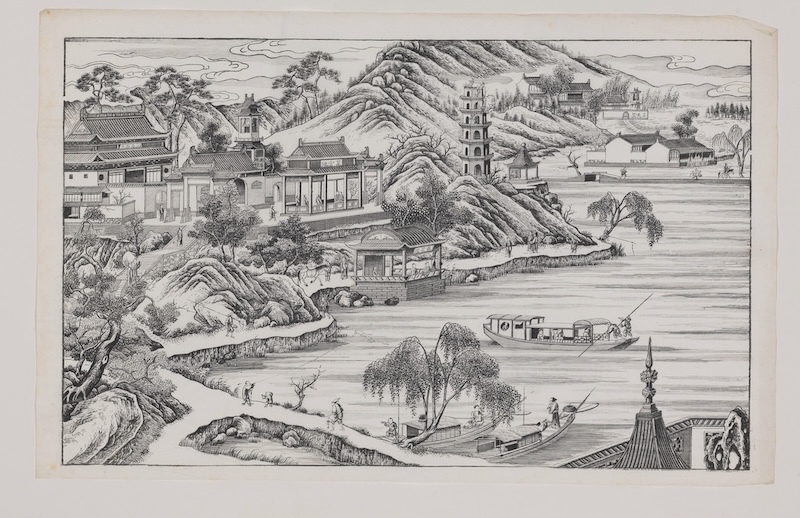

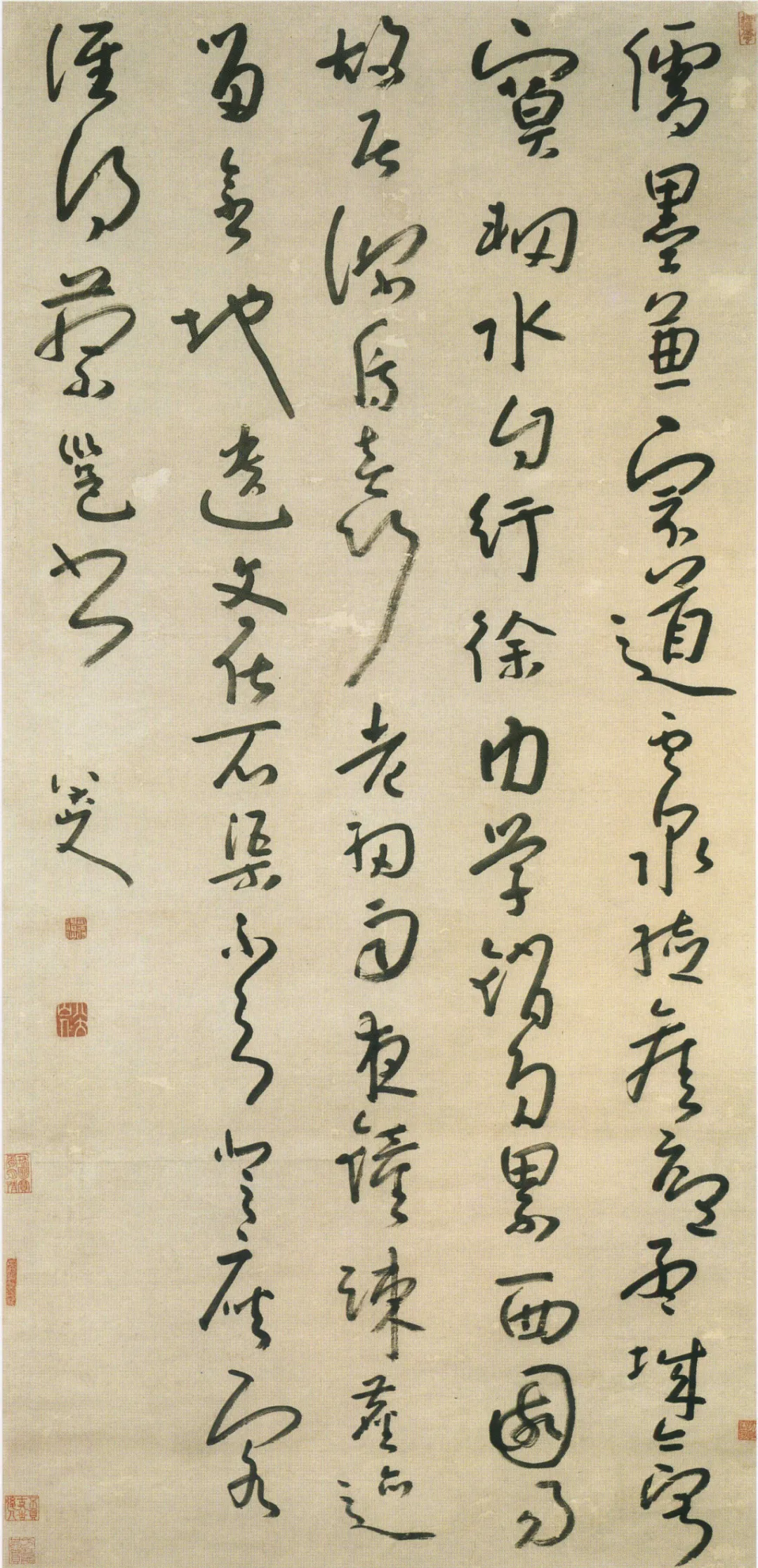

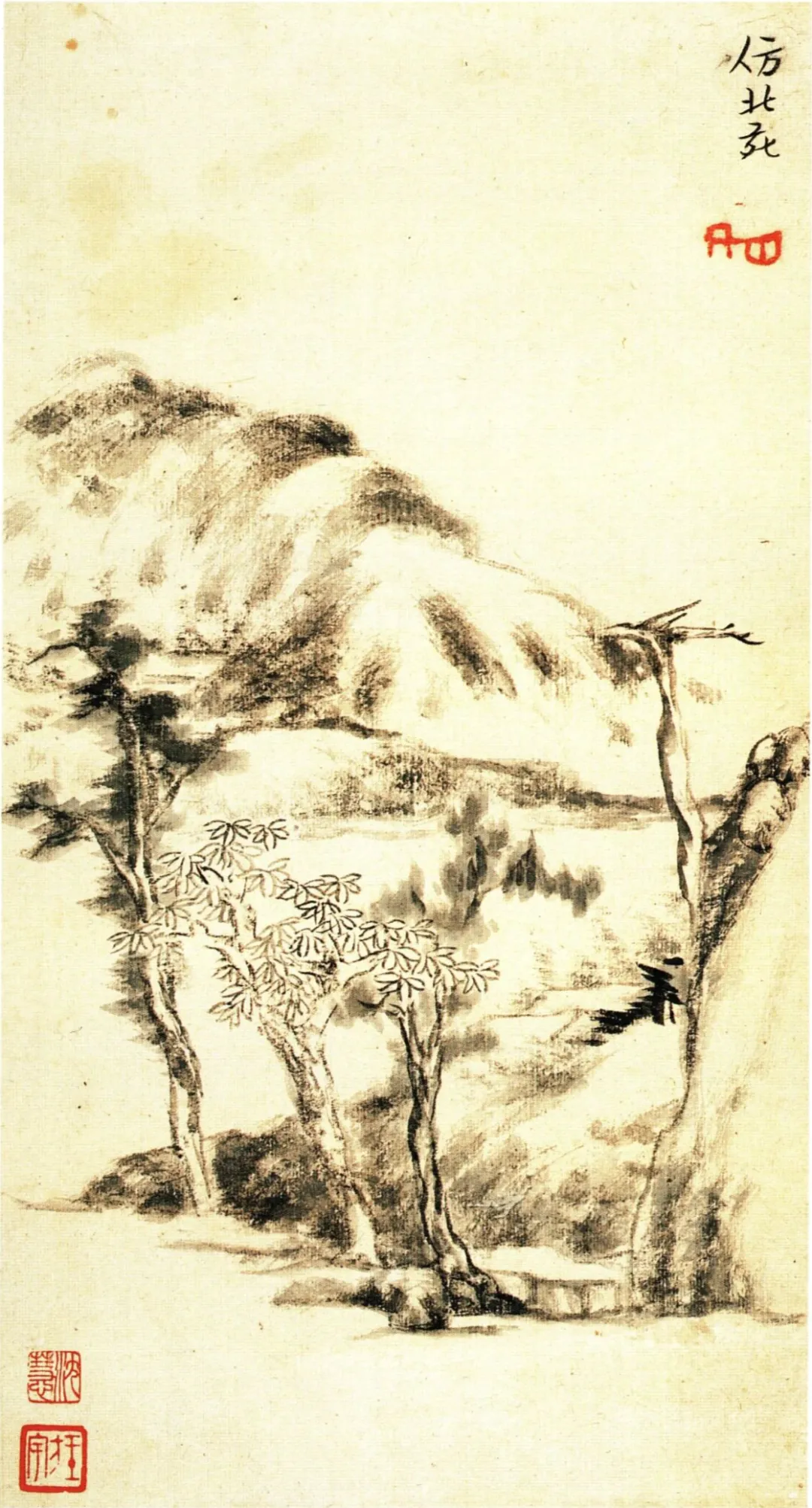

Bada Shanren's running-cursive script hanging scroll by Geng Wei, formerly in the collection of Wang Fangyu.

In 1985, before I went abroad to study, I established correspondence with Mr. Wang Fangyu through the introduction of Ms. Yang Hesong, the wife of Professor Yuan Xingpei. In 1986, I went to Rutgers University in New Jersey to study comparative politics in the Department of Political Science. After arriving in the US, I discovered that Mr. Wang's home was not far from our school. After learning to drive, I would often visit his home to ask him for advice, and gradually we became acquainted. I also got to know his son, Mr. Wang Shaofang. In 1990, I changed my major and went to Yale University to pursue a doctoral degree in art history. Mr. Wang was one of my recommenders.

After the 1990s, Mr. Wang developed some heart problems and underwent surgery. Generally speaking, Mr. Wang was in good health and had a sharp mind. Heart surgery is quite advanced in the United States, so everyone (including Mr. Wang himself) assumed there would be no problem with the surgery. Unexpectedly, a few days after the surgery, while talking to his son in the hospital room, he suddenly suffered arrhythmia and died suddenly. Before the surgery, Mr. Wang was optimistic about his post-operative prognosis and did not leave a will related to his collection. His wife had also passed away several years prior, making the disposal of his father's estate a major problem for his son, Wang Shaofang. Fortunately, Mr. Wang had organized his best paintings before his death and instructed his son to donate this collection to a museum after his passing, benefiting the academic and artistic communities.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Yale University Art Museum, and the Freer Gallery of Art all sought Mr. Wang's donation. Mr. Zhang Zining, then head of the Chinese Painting and Calligraphy Department at the Freer Gallery of Art, was a reliable and scholarly man, trusted by Wang Shaofang. After careful consideration, Wang decided to donate the collection to the Freer Gallery of Art. The Freer Gallery of Art is a public Asian art museum in Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States.

When Wang Shaofang was negotiating the donation with the Freer Gallery of Art, he made a decision: to affix his parents' seals to these works so that future generations would know that these items had once been part of his family's collection. He also preserved a portion of his father's collection, hoping that these works would also be stamped with seals, so that future researchers could understand the complete collection of Bada Shanren by Wang Fangyu and his wife through the seals. Before his death, Mr. Wang Fangyu had affixed his seals to some of the paintings and calligraphy, but most of them only bore his own seal. Wang Shaofang believed that since it was a joint collection of his parents, his mother's seal should also be added.

Bai Qianshen carved a seal for Wang Fangyu.

Who should affix their seals to these ancient paintings and calligraphy? Wang Shaofang thought of me because I knew how to carve seals and had carved seals for Mr. Wang before. I often affix seals to my calligraphy, but I had only done so once before, on ancient paintings and calligraphy. In the early 1990s, Ms. Zhang Chonghe asked me to inscribe a long scroll of Wen Zhengming's running-cursive script in her collection. I affixed my seal after writing the inscription at the end of the scroll, but not on the main painting itself. This time, being asked by Wang Shaofang to affix the seal was different; it would be directly on the painting. Although the pressure was considerable, Mr. Wang had been kind to me, and I felt obligated to do so.

three

Wang Shaofang bought me a plane ticket, and on May 4th I flew to New Jersey and stayed at Wang Shaofang's home. For stamping, one needs good ink, so Mr. Zhang Zining asked the renowned seal engraver Mr. Wu Zijian to buy top-quality ink from the Xiling Inkpad Factory in Shanghai, which was then shipped to the United States. When I arrived in New Jersey, the ink had already arrived a few days earlier.

Mr. Wang is a calligrapher and has many seals. My first task was to select suitable seals for his ancient paintings and calligraphy. Since some works are large while others are small album leaves, the seals had to be chosen according to the size of the painting. Scholars who study the history of painting and calligraphy know that Emperor Qianlong collected many paintings and calligraphy works and liked to stamp them with his seals. Sometimes he would stamp a huge seal on a very small painting to demonstrate his supreme imperial power, but this disrupted the harmony of the painting and greatly affected the viewing experience, drawing criticism from later generations. Private collectors generally wouldn't do this. I first selected some of Mr. Wang's seals that were suitable for stamping as collector's seals, generally choosing those that were relatively neat and orderly. Mr. Qiao Dazhuang, Mr. Dong Zuobin, Mr. Wang Zhuangwei (a seal engraver from Hebei who traveled to Taiwan), and Mr. Xu Yunshu (a seal engraver from Shanghai residing in New York) all carved seals for Mr. Wang. When stamping collector's seals on ancient paintings and calligraphy, large sizes and bold, unrestrained styles are not advisable; therefore, modern collector's seals are mostly characterized by a steady and orderly style. Although Mr. Wang possessed a seal bearing the name of Qi Baishi, it was not suitable as a collector's seal for his calligraphy and paintings. Mr. Wang's wife, Ms. Shen Hui, had a small red seal, which was quite appropriate for small works. However, it would appear too small for large pieces. Fortunately, Mr. Wang had commissioned a larger round red seal, "Fang Hui Gong Shang," which was perfectly suited for large scrolls.

After selecting the seals, the next step is cleaning them. Many calligraphers don't clean their seals frequently, and the oily ink can stick to the recessed parts of the seal, accumulating over time and making the edges of the stamped seal unclear. When stamping collector's seals on ancient paintings and calligraphy, the stamps should be clean and clear, allowing the exquisite seal carving art to complement the painting. I soaked the seals in warm water for a while, then gently cleaned them with a toothbrush and soap; too much force would damage the seal surface. After cleaning, I dried them and let them air dry for a while before using them for stamping. Normally, I'm not this meticulous when writing or stamping. This time, entrusted with a task, I wanted to do my best, to do justice to Bada Shanren from three hundred years ago, to Mr. Wang Fangyu who has always supported me, and to a public museum.

Ancient paintings and calligraphy have survived countless wars and calamities, a truly fortunate occurrence, inspiring a sense of awe in us. Printing on them is a challenge, allowing no room for error. There are four key aspects to consider when printing on ancient paintings and calligraphy: First, the placement of the seal. Generally, collector's seals are placed in a corner. Since these are ancient paintings and calligraphy, they often bear the marks of previous collectors, which can be placed on top of existing seals. If several seals have already been placed on them, the seal must be placed next to the previous one. In this case, the size of the seal, whether it's in red or white ink, and its harmony with previous collector's seals must all be considered. Second, the seal's orientation must be absolutely correct. Mr. Wang himself once stamped his own piece with the seal upside down. We occasionally see similar examples on ancient paintings and calligraphy. This is the worst-case scenario for stamping. Correcting such an error requires patching during remounting, but this increases the suspicion of forgery. Third, the hand must be exceptionally steady when stamping. Because ink paste is oily, it tends to slip on smooth paper used for calligraphy and painting. Even slight hesitation or trembling of the hand can cause the edges of the ink to overlap or widen, affecting the appearance. Fourth, care must be taken to prevent accidental smearing of ink paste onto other parts of the artwork. Once ink paste adheres to the artwork, it is not easy to remove.

Wang Fangyu and Shen Hui's collection of Bada Shanren's landscape album leaves

I mark the top or side of each stamp to indicate which side is the front, ensuring that the stamp is printed in the correct orientation.

Before stamping each piece of calligraphy and painting, Wang Shaofang and I would unfold the work and carefully choose a suitable location. To prevent the ink from smudging onto the painting, Wang Shaofang bought some waterproof transparent paper beforehand. We used this paper to completely cover the entire painting, leaving only the area for the seal exposed. Sometimes, the exposed area was no more than five square centimeters, or even only two or three square centimeters. This was very safe; if the seal accidentally fell off, it would land on the covering paper and not touch the painting.

After everything was ready, I finally began stamping, feeling a little nervous. I thought that if the collection were my own, the pressure would be less. But since I was entrusted with this task, the situation was different. I picked up the chosen seal, gently dipped it in the ink, and repeatedly checked whether the ink had evenly covered the entire surface. Wang Shaofang sat to my left, repeatedly verifying with me that the seal's orientation was correct. Then, I slowly moved my hand to that position and stamped the paper. I paused briefly, then slowly lifted it to avoid unevenly spreading the ink. One paper after another, one after another, I stamped over a hundred times. Of those hundred-plus stamps, only one was slightly thicker at the edge due to a slight tremor in my hand; the rest were perfectly positioned, applied evenly, and the characters were clear—a true success.

Because the whole process was very slow and time-consuming, it took us two days. After completing the final printing, I felt a huge sense of relief. However, the intense concentration was quite tiring. What should have been a relaxing and elegant task had turned into a strenuous activity. I have a habit of keeping a diary, and my entry for May 5th reads: "Getting the seal at Shao Fang's house. Zhang Zining and their director came to sign the contract. The seal is complete. Everything went smoothly, no major problems." On May 6th, I flew back to Boston.

Four

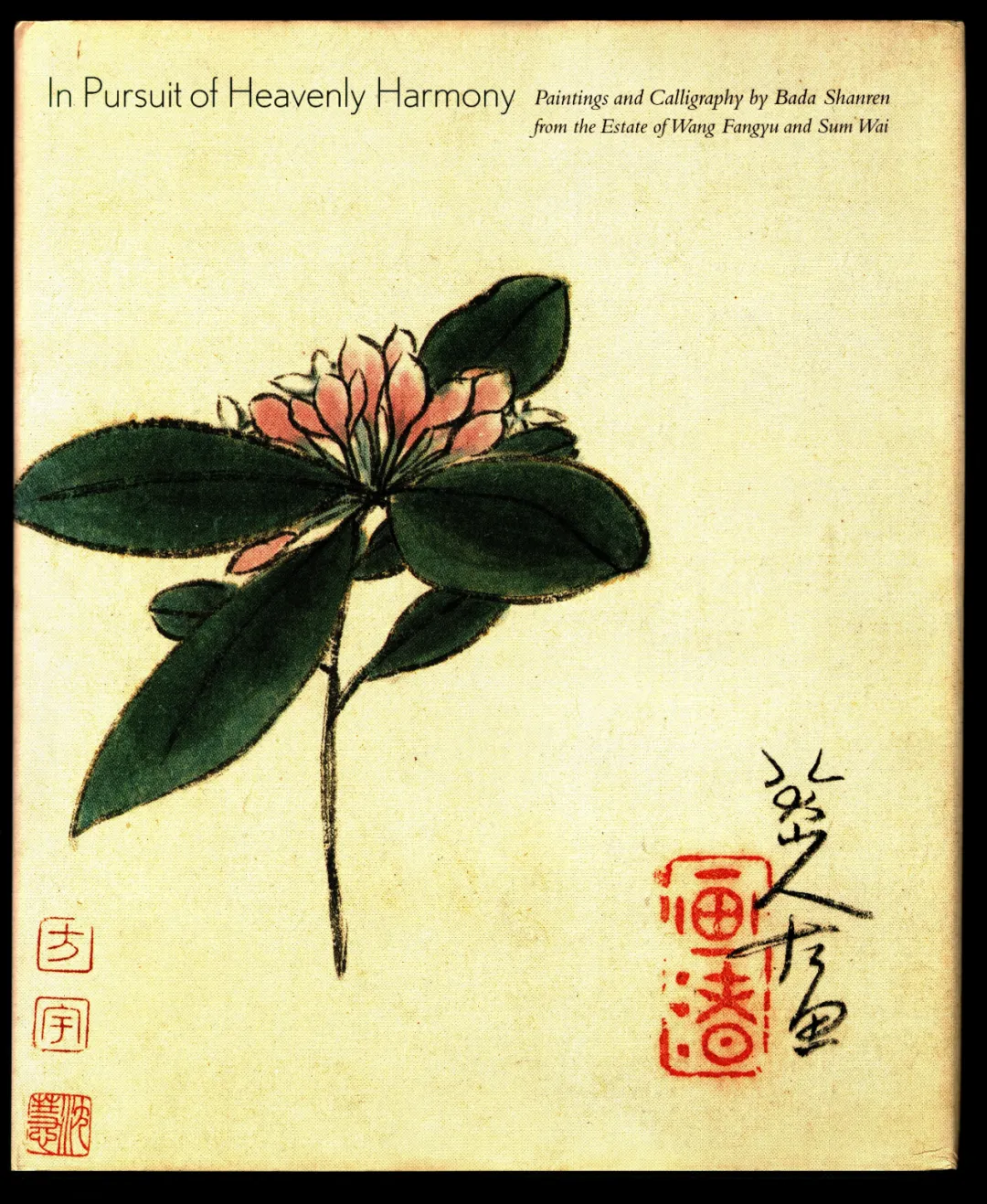

Soon after, some of Bada Shanren's paintings and calligraphy from Mr. Wang Fangyu's collection were successfully acquired by the Freer Gallery of Art. In 2003, after five years of preparation, the exhibition "Tian Ni: Wang Fangyu and Shen Hui's Collection of Bada Shanren's Paintings and Calligraphy" was held at the Freer Gallery of Art. The exhibition catalog of the same name, co-authored by Zhang Zining, Bai Qianshen, and An Mingyuan, was published at the same time, which was a tribute to Mr. Wang Fangyu's contributions to the collection and research of Bada Shanren's paintings and calligraphy.

Catalogue of *Tian Ni: Wang Fangyu and Shen Hui's Collection of Bada Shanren's Calligraphy and Painting*, Zhang Zining, Bai Qianshen, and An Mingyuan, Freer Gallery of Art, 2003.

As mentioned earlier, Zhang Yanyuan's *A Record of Famous Paintings Through the Ages* discusses collector's seals. Collector's seals existed during the Five Dynasties and Song Dynasty, and this tradition continued uninterrupted. However, after 1949, the situation changed significantly. Due to the circumstances at the time, although antique shops still openly sold antiques, and private transfers between collectors occurred, the activity seemed sluggish. In the 1980s, I saw some elderly gentlemen in Shanghai affixing their seals to their collections. For example, in 1985, my teacher, Mr. Jin Yuanzhang, took me to visit the collector Mr. Zheng Meiqing in Shanghai to see his collection of Fu Shan's *Lament for My Son Scroll*, which bore Mr. Zheng's collector's seal. The practice of stamping ancient paintings still exists among a small group of people.

Wang Shaofang asked me to affix my seal to his father's old collection before it entered the museum, because he considered that once cultural relics are in the museum, they cannot be stamped again. However, this is the current rule. On some ancient paintings in the Shanghai Museum's collection, you can still see some seals affixed by the Shanghai Cultural Relics Management Committee after 1949. The placement of the stamps, the artistic quality of the seals, and the ink used are all very particular. It's clear that in the 1950s, it was still permissible to affix seals to publicly owned cultural relics. Our predecessors still valued this. Among the collector's seals I've seen on ancient paintings and calligraphy, Zhang Daqian's are considered very refined. He used good seals with elegant colors, and they looked very vibrant on the ancient paintings.

Nowadays, fewer people possess this level of refinement. We often see collectors' stamps placed improperly. I once saw a newly stamped book in a prestigious university library with a thread-bound book; the effect was less than ideal, detracting from the book's aesthetic appeal. Ancient Chinese books are beautiful and elegant; when stamping them, a thin, sturdy plastic sheet should be placed underneath to ensure even pressure on the paper and a clear imprint.

Since the turn of the millennium, the private collecting and auction markets in mainland China have been very active, with art transactions becoming increasingly frequent, and many paintings and calligraphies entering private collections. These new collectors have also begun to stamp their collections with their seals. For example, Mr. Lin Xiao, the owner of Jinmotang, is renowned at home and abroad for his collection of ancient calligraphy masterpieces, and he often stamps his collection with his seal. However, in the 1990s, the auction market in mainland China was just beginning, and private collecting activities were not yet so active. I stamped a batch of works by a great painter in the history of Chinese art with my collector's seal within two days. This experience was both novel and exciting for me, and I still remember it vividly.

(This article was originally published in Volume 12 of "Anecdotes", published by Zhonghua Book Company in October 2025, and was originally titled "I Printed Seals for Ancient Paintings and Calligraphy")