What should one look for when collecting a seal? Three key elements: material, seal carving, and craftsmanship. A seal possessing all three qualities is a fine piece. The late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China marked a crucial turning point in the art of seal carving, elevating it from a mere "skill" to a "philosophy of mind," with literati deeply involved in its creation. Zhao Zhiqian pioneered a new style, Wu Changshuo founded the "Wu School," Huang Shiling established the "Yishan School," and Qi Baishi, with his bold and unrestrained style, developed a strong personal style, completing the transformation of classical seal carving into modern aesthetics.

The Paper learned that on November 9th, China Guardian's 2025 Autumn Auction will hold two special sessions: "Qingning – Seal Carving Art" and "Essence of Seal Carving". The former focuses on academic context, systematically tracing the development and ideological transformation of seal carving art since the late Qing Dynasty, much like reading a seal carving textbook; the latter, based on the "Yanghetang" collection of Mr. Zhang Tiangen, founder of Hongxi Art Museum, will showcase the academic rationality and humanistic warmth of seal stone collecting.

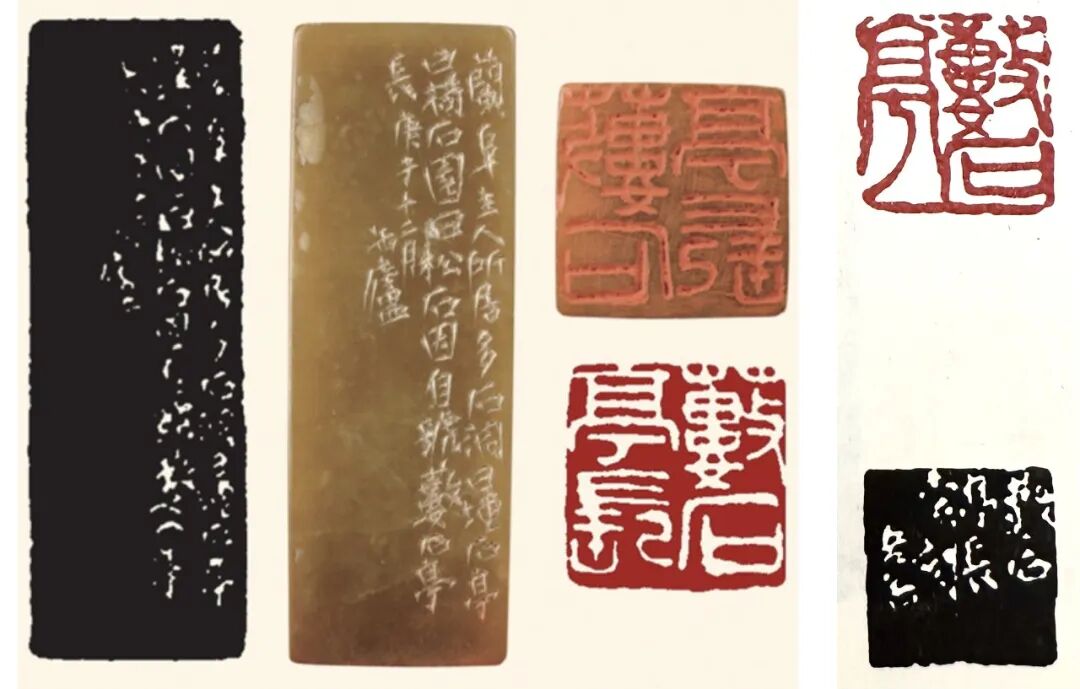

The seals featured at the China Guardian Autumn Auction are as follows: Top left: Zhao Zhiqian's personal seal made of Qingtian stone; Top right: Qi Baishi's Shoushan stone seal with the inscription "Still there are plum blossoms, old friends"; Bottom left: Wu Changshuo's Shoushan hibiscus stone square seal with double dragon knobs, inscribed "The gardener's home is in the bamboo cave, called the bamboo lintel"; Bottom right: Xu Sangeng's Shoushan hibiscus stone dragon knob seal with the inscription "Shangyu Xu Sangeng Youhai".

From seals and inscriptions to scholar's refined objects

From official tools to scholarly objects, the evolution of seals has witnessed the transformation of Chinese culture from focusing on social function to caring for the inner world, becoming a unique art that carries a thousand years of cultural sentiment within a small space.

From the pre-Qin period to the Sui and Tang dynasties, the core function of seals was "credential verification." The ancient seals of the Warring States period, with their innocent and unrestrained style, served as carriers of power and credibility, and were widely used in politics and commerce. During the Qin and Han dynasties, the seal system reached its zenith, with Han seals being particularly dignified and robust, setting a model that was difficult for later generations to surpass. At that time, seals were mostly stamped on clay to prevent tampering, making them purely practical objects.

The turning point occurred during the Song and Yuan dynasties. With the widespread use of paper, the method of using seals changed from sealing with clay to applying red ink, providing the conditions for their integration into calligraphy and painting. The rise of literati painting allowed artists to stamp their names and studio names on their works, thus giving seals both decorative and expressive functions. More importantly, the flexible texture of stone replaced the hardness of bronze and jade, allowing literati to carve seals themselves. Yuan dynasty figures like Zhao Mengfu further advocated "learning from the ancients" in theory, laying the aesthetic foundation for seal carving art.

The system is composed of three main parts.

The art of seal carving has undergone several fundamental transformations throughout its long history, the most profound of which occurred from the late Qing Dynasty to the early Republic of China. This period marked a crucial turning point, elevating seal carving from a mere "technique" to a "philosophy of the mind." It established seal carving as a comprehensive literati art integrating epigraphy, calligraphy, painting, and literature. This transformation did not happen out of thin air; its core driving force was the revival of epigraphy. During this period, a large number of ancient artifacts, such as bronzes, inscriptions, clay seals, and roof tiles, were discovered and studied, opening up an unprecedented resource for artists.

Artists were no longer limited to Qin and Han dynasty seals, but turned their attention to all ancient written relics. Zhao Zhiqian was a prime example. He creatively incorporated the textual styles of Qin weights and measures, imperial edicts, Han dynasty brick inscriptions, Wei and Jin dynasty steles, and even votive inscriptions into his seals, proclaiming the slogan "Seek seals beyond seals," thus opening up an infinitely vast new world for seal carving.

Zhao Zhiqian's postscript to Zhang Liu's compilation of "Old Jiang's Seal Collection" shows Zhao Zhiqian's seal in the lower left corner.

This was the period with the most concentrated number of masters and the most distinctive styles in the history of seal carving, forming a clear lineage of schools: Zhao Zhiqian pioneered a new style, Wu Changshuo founded the "Wu School", Huang Shiling founded the "Yishan School", and Qi Baishi formed a strong personal style with his bold strokes, completing the transformation of classical seal carving into modern aesthetics.

The collection of China Guardian's 2025 Autumn Auction "Qingning - Seal Carving Art" can be roughly divided into three parts: seal carvings by famous artists, exquisite stones, and works by master carvers. Following this framework, it's like reading a textbook on seal carving.

[Masterpieces Section]

Since the rise of epigraphy in the late Qing Dynasty, seal carving art broke through the limitations of traditional calligraphy models, pursuing the spirit of ancient seals and the essence of epigraphy. Zhao Zhiqian incorporated calligraphy into seal carving, pioneering a new school; Huang Mufu integrated Han Dynasty techniques into his new style, achieving elegant composition; Xu Sangeng was graceful and elegant, his brushstrokes flowing like the wind; Wu Changshuo excelled in spirit, his works powerful and vigorous; Qi Baishi transformed the ancient into the new, returning to simplicity and authenticity, elevating seal carving beyond mere technique to a realm of spiritual expression. The history of seal carving over the past century is not only an art history of incorporating calligraphy into seal carving, but also a history of literati culture permeated by the spirit of epigraphy.

The portrait of Zhao Zhiqian in "Portraits of Qing Dynasty Scholars" was painted by Yang Pengqiu.

Zhao Zhiqian initially studied the Zhejiang School, later integrating techniques from the Anhui School (Deng Shiru) and the Zhejiang School (Ding Jing). He pioneered the concept of "seeking seals beyond seals," and with his comprehensive artistic talent and bold innovative spirit, he became a pivotal figure in the late Qing Dynasty's art world, a pivotal figure in the transformation of seal carving. He achieved success in calligraphy, painting, and seal carving, but his breakthroughs in seal carving were particularly remarkable. In this China Guardian 2025 Autumn Auction, the Department of Antiques and Classical Furniture presents three items related to Zhao Zhiqian, providing clear clues for observing the evolution and dissemination of his artistic thought. Among them is a seal carved by Zhao Zhiqian for his own use from Qingtian stone, with the inscription on the side: "Upon arriving in the capital, I obtained this stone and happily carved it. Recorded by myself in the summer of Guihai year." This records his initial arrival in the capital and his youthful exuberance. Although small, this seal combines carving and brushwork, with a full structure and lines that are both sharp and resilient, representing an early concrete result of Zhao's concept of "incorporating stele inscriptions into seal carving." This work has been recorded in more than 30 books since then, and it was also stamped on the "Fan with Copy of Liu Mengyang's Stele Inscription" in the collection of the Palace Museum. It has been recorded in numerous books and is quite a remarkable work.

Zhao Zhiqian carved a personal seal from Qingtian stone, 1.4×1.4×5 cm.

Inscription on the side: I acquired this stone as soon as I arrived in the capital, and was delighted to carve it. Recorded by myself in the summer of Guihai year.

Seal inscription: Seal of Zhao Zhiqian.

Zhao Zhiqian's seal carving is primarily characterized by its unprecedented ability to "integrate" styles. He not only harmonized the styles of the Anhui and Zhejiang schools but also drew inspiration from all ancient written relics: starting from the foundation of Qin and Han dynasty seals, he extensively absorbed artistic elements from Qin weights and measures, imperial edicts, coins, mirror inscriptions, Han lamps, Han bricks, clay seals, and even the steles and statues of the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties. Wherever there was writing, it could serve as a teacher; this inclusive approach greatly broadened the resource scope of seal carving art, paving a new and expansive path for the development of seal carving over the past six hundred years.

Zhao Zhiqian's artistic innovations were deeply rooted in the flourishing of epigraphy in the mid-19th century. At that time, the study of epigraphy was prevalent, and the spirit of stele inscription permeated the minds of scholars. Scholarship and art converged here, prompting seal carving and calligraphy to shift from mere imitation of the past to conscious creation. Positioned at this pivotal point of change, he was well-versed in classics, history, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving, completing a magnificent transformation from adhering to ancient methods to establishing a new style. He pushed the concepts of "incorporating calligraphy into seal carving" and "incorporating stele inscriptions into calligraphy" to their extreme, thus becoming a watershed figure in the late Qing dynasty literati art, bridging the past and the future.

A partial view of Zhao Zhiqian's "Copy of Liu Mengyang's Stele Inscription" in the collection of the Palace Museum.

Xu Sangeng, a seal engraver and calligrapher of the Qing Dynasty, was renowned for his unique "Wu-style flowing brushstrokes" seal engraving art, which blended the ancient charm of the Qin and Han dynasties with his personal innovation. In his middle age, his seal engraving style shifted from rustic simplicity to elegant and graceful beauty, with sharp and incisive knife work, exerting a profound influence on the seal engraving world in the late Qing Dynasty and Japan. This time, a Shoushan hibiscus stone dragon-knob seal engraved by Xu Sangeng, inscribed "Shangyu Xu Sangeng Youhai," will be auctioned. The side inscription reads "Old Sleeve Self-Engraved," one of his pseudonyms, reflecting his carefree attitude.

Xu Sangeng carved a Shoushan hibiscus stone dragon-knob seal with the inscription "Shangyu Xu Sangeng Youhai" (3.6×3.6×5 cm).

Inscription on the side: Carved by Lao Xiu himself

Seal

Huang Shiling, courtesy name Mufu, was a master seal engraver who founded the "Yishan School" in the late Qing Dynasty. His seal engraving style was clean and upright, with a sense of danger within its balance, and had a profound influence on the field of calligraphy and seal engraving in the late Qing Dynasty.

Huang Shiling carved a square seal with a beast-shaped knob on a Shoushan Tianhuang stone, bearing the inscription: "Heaven and earth are but a temporary lodging, time is but a fleeting guest. What use are wealth and honor to my dwelling? Here I am carefree, lively and vibrant." Bo Hui, using the name "Ji Zhai" for Yan Zhai, added these twenty-four lines as an inscription, commissioning Mu Fu to write the calligraphy.

Seal inscription: Jizhai 2.6×2.6×5.1; 54.7g

This "Jizhai" square seal, made of Shoushan Tianhuang stone with a beast-shaped knob, is a complete work of Huang Shiling's seal carving art. Its value lies not only in the inherent nobility of Tianhuang stone itself, known as the "Emperor of Stones," with its warm, condensed texture and restrained luster; but also in its integration of Huang Shiling's seal carving, calligraphy, and literary cultivation. The stone is orange-yellow in color, with a smooth, translucent texture resembling amber; the carved beast knob is refined in its craftsmanship, with strong lines and a majestic form. The "Jizhai" inscription on the seal face is in the style of Han dynasty calligraphy, with a balanced layout and elegant style; the inscription on the side, "Heaven and earth are a temporary lodging, time is a fleeting guest. If wealth and honor are not enough for my dwelling, where can I find true freedom and liveliness?" conveys the sentiment that life is but a temporary sojourn, echoing the inscription on the seal. It is a famous work that has been published and recorded multiple times in Huang Shiling's seal albums.

This seal was carved for my close friend "Bo Hui". Bo Hui is Yu Dan, a native of Wuyuan, Jiangxi Province. He was skilled in poetry, calligraphy and painting, and became acquainted and cherished Huang Shiling through their shared interest in seal carving. Tianhuang stone is extremely rare, and the fact that this stone was used to carve a seal for a friend shows the depth of their friendship and the importance they placed on each other.

Huang Shiling's seal carving principles emphasized "not striking the edges or corners," rejecting the deliberate mottled style common in the late Qing dynasty. His knife work was crisp and precise; his red seals were vigorous and upright, while his white seals drew inspiration from the complete beauty of Han dynasty cast seals, using a thin-bladed chisel to restore the spirit of the original bronze seal carving. His overall style is fluid within its evenness, elegant within its strength. The composition is naturally balanced, seemingly simple yet containing ingenious details; the side inscriptions are written in the Wei style with a chisel stroke, forming a unique style. Like Zhao Zhiqian, he expanded the scope of inspiration for seal carving, especially emphasizing the spirit and charm of bronze inscriptions from the Three Dynasties. His disciple Li Yinsang once commented, "Huang Shiling's learning lies in ancient stone inscriptions, while Huang Shiling's learning lies in bronze inscriptions," demonstrating a deep understanding of his teacher's philosophy.

Wu Changshuo carved a square seal with a double-dragon knob made of Shoushan hibiscus stone, bearing the inscription "The gardener's home is in the bamboo cave, the bamboo lintel is called Bamboo Grove".

Seal inscription: The gardener's family lives in the bamboo cave, their name on the bamboo lintel. 3.5×3.5×7.4cm

Inscription on the side: Carved for the gardener in the second month of Jia Chen year, in a clay pot.

The Qing Dynasty was an era of great development for literati seal carving art, a peak in the history of seal carving besides the Qin and Han Dynasties. There were many famous artists, many schools, and many masterpieces. However, upon careful examination, most of these surviving works are made of ordinary materials, and it is rare to find works that simultaneously possess the beauty of stone, seal, and craftsmanship.

Wu Changshuo carved a square seal with a double-dragon knob made of Shoushan hibiscus stone, inscribed with "The Gardener's Home is in the Bamboo Cave, Named Zhumei." The seal's owner was Min Yong-ik, a Korean nobleman. Wu Changshuo carved over a hundred seals for him throughout his life, making them true confidants. This seal was made in 1904, when Wu was 61 years old. The nine-character inscription, with its grid layout and robust lines, shows the artist's skill in using the knife to strike the seal face at different angles, creating a weathered effect. It is a typical example of Wu Changshuo's imitation of clay seals. The seal material itself is well-proportioned and elegant, with a soft and beautiful color and a simple and ancient carving style. Shoushan hibiscus stone is considered the "Queen of Stones," on par with Tianhuang stone. Its texture is warm and smooth, and its colors include white, yellow, red, and multicolored varieties. Mining increased in the late Qing Dynasty, and its use became more widespread. Many fine stones were produced during this period, leading to the contemporary description: "Like Xi Shi without makeup, her natural beauty is even more captivating."

Wu Changshuo carved a Shoushan hibiscus stone seal with the inscription "Shoushi Pavilion" (薮石亭), measuring 4.3 × 4.3 × 6.6 cm.

Side inscription: Ku Tie

The Shoushan hibiscus stone seal "Shushi Pavilion" was created by Wu Changshuo for Min Yeong-ik, a member of the Korean royal family who was exiled at sea, around 1900. "Shu" means "gathering" or "collection," and the name derives from the abundance of stones at Min Yeong-ik's residence: "The residence of the Master of Lanfu was filled with stones; the cave was called 'Chunshi,' the pavilion 'Yishi,' and the garden 'Songshi,' hence he called himself 'Shushi Pavilion Master.'" Wu Changshuo carved at least four seals related to Shushi Pavilion for Min, and this seal is the largest of them, measuring 4 centimeters square.

Min Yeong-ik (1860-1914), also known as Lan-gai and Yuan-ding, was the nephew of Empress Myeongseong of Joseon and a powerful minister who served as a relative of the empress. He was seriously injured in the Gapsin Coup in 1884 and subsequently fled to China, residing in Shanghai. He was quite wealthy and became an important artistic confidant and patron of Wu Changshuo, especially renowned for his orchid paintings. He, Wu Changshuo, and Gao Yong were collectively known as the "Three Masters of Haiyu" (orchid paintings). Wu Changshuo carved over three hundred seals for him, the most of any collector, showcasing diverse styles and exquisite craftsmanship, demonstrating the depth of their friendship.

However, when Min commissioned a seal, he also had to pay according to the standard rates. According to the "Collection of Seal Carving Rates Since the Late Qing and Republican Periods" appended to Zhu Qi's book "A Small Path to Observation: Seal Carving by Chinese Literati", in 1899, Min Yongyi commissioned Wu Changshuo to carve a seal through the introduction of Pan Xiangsheng. The rate was six cents per character, and for inferior stones, the rate was doubled, which was one yuan and two cents per character. According to the market price at the time, this amount was quite considerable.

Left: The Stele of Sou Shi Pavilion in the collection of Zhejiang Provincial Museum; Right: The Stele of Sou Shi Pavilion carved by Wu Changshuo.

"Shǒu Shī Tǐng" is a representative work of Wu Changshuo's bold red seal script. The left, right, and top edges are all tightly packed, except for the bottom, which is left empty, giving a feeling of being impenetrable. The character "亭" (tíng) stands alone, towering high, especially the vertical stroke at the bottom of the character, which goes straight down like a rainbow, resembling an ancient vine hanging with dew, strong and elastic, instantly invigorating the spirit of the entire seal. The composition of this seal is well-balanced in terms of density and sparseness, with a balance of emptiness and fullness. It is very similar to the smaller "Shǒu Shī Tǐng" in the collection of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, but its momentum is more magnificent. The two seals are like pearls of different sizes, beautifully complementing each other.

Qi Baishi's Shoushan stone seal, inscribed with "The plum blossoms still remain, a testament to old friends," measures 2.9 x 2.9 x 6.7 cm.

Side inscription: Seal of my esteemed brother Zhizhi, printed by your younger brother Qihuang, Renxu year.

The Shoushan stone seal bearing the inscription "The plum blossoms remain, a testament to our old friendship" was carved by Qi Baishi in 1922 for his friend Ling Zhizhi. Ling Zhizhi, a graduate of the Jiangsu Normal School, served as a member of the Jiangsu Provincial Assembly in 1909 (the first year of the Xuantong reign of the Qing Dynasty). After the establishment of the Republic of China, he served as a member of the Nanjing Provisional Government Assembly. In 1917, he went to Beijing to serve as a counselor in the Ministry of Finance. Qi Baishi traveled north that year, where he met Ling Zhizhi, and they formed a deep friendship.

The seal is square and upright, exuding an ancient and refined air.

The seal is square and upright, with a spacious and well-balanced layout, exuding an air of antiquity. The inscription, "The plum blossoms remain, a familiar friend," is taken from a poem accompanying a painting, conveying a steadfast and noble spirit and expressing the deep affection between the artist and his friend. The carving technique is fluent and deliberate, with a stable and vigorous structure in the side inscription. This seal is not only one of Qi Baishi's important early works before and after his move to Beijing, but it also testifies to the deep ties between him and his circle of literati, making it an important material example for studying the history of Qi Baishi's seal carving art and social relationships.

[Good Stone Section]

Shoushan, Qingtian, and Changhua are the three major types of seal stones, with Tianhuang stone standing out as the "Emperor of Stones." Its warm texture and clear color have made it a favorite among collectors throughout history. The evaluation of seal stones has always been based on the "three essential elements": the beauty of the material, the exquisite carving technique, and the ingenuity of the design. Only those stones that possess all three qualities can be considered masterpieces in the world of seal carving.

The beauty of literati seal stones lies not only in their composition and grandeur, but also in the purity of their materials and the ingenuity of their carving. Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, using stone as a seal stone has gradually become mainstream, and the materials used for seal stones have become increasingly warm and lustrous, making them easier to carve. Shoushan stone is most admired for its fine texture and rich color, with Tianhuang stone being the most prized among all stones, possessing delicate texture and a lustrous sheen, earning it the title of "Emperor of Stones." Chicken blood stone, with its radiant colors and dignified appearance, has always been treasured by royalty and scholars.

Qing Dynasty Shoushan Tianhuang Stone Auspicious Beast Knob Square Seal

Qing Dynasty Shoushan Tianhuang Stone Auspicious Beast Knob Square Seal

Inscription: A dappled horse, a thousand pieces of gold, call the boy to exchange them for fine wine.

The inscription on the Shoushan Tianhuang stone square seal with a mythical beast knob comes from Li Bai's poem "Bring in the Wine," which includes the lines, "A dappled horse, a thousand pieces of gold, call the boy to exchange them for fine wine," expressing a bold and unrestrained spirit.

Another early Qing dynasty Shoushan Tianhuang stone natural top rectangular seal, with a simple and grand shape.

Early Qing Dynasty, Shoushan Tianhuang Stone Rectangular Seal with Natural Top, 4.7×2.6×6.7cm; 171.7g

This early Qing dynasty Tianhuang stone natural top rectangular seal weighs 170 grams. Its color is like beeswax, its texture is solid, and its radish-like veins are clearly visible. It can be described as a large and high-quality piece, which is quite rare.

A large square seal made of Shoushan Tianhuang stone with a dragon-shaped knob, dating from the early Qing Dynasty. 3.5×3.5×8.1cm; 180.8g

In terms of carving craftsmanship, this large square seal made of early Qing Dynasty Shoushan Tianhuang stone with a dragon-shaped knob showcases the exquisite carving skills of that time. This large square seal weighs 180 grams, with a square and neat body, clean texture, and a deep and rich yellow color with reddish tinge. The knob is carved with a dragon passing through the ring, and the shape is ancient and shows the influence of bronze ware, possessing a solemn atmosphere rarely seen in Qing Dynasty Tianhuang seals.

A rectangular seal made of Shoushan Tianhuang stone with a dragon and tiger knob, dating from the Qing Dynasty. 4.7×2×3.3cm; 58.5g

Mid-Qing Dynasty, Shoushan Hibiscus Stone Pair of Seals with Lion Buttons (4.3×4.2×8.1cm, 4.2×4.2×8.3cm)

In addition, the rectangular seal with a dragon and tiger knob made of Shoushan Tianhuang stone from the Qing Dynasty, and the pair of seals with lion and cub knobs made of Shoushan Furong stone from the mid-Qing Dynasty, are warm in color and simple in shape.

Hibiscus stone is known for its warm and elegant texture, and the Hibiscus stone from General Cave is a rare and exquisite piece. This pair of Hibiscus stone seals with lion and lion knobs is white with a hint of yellow, and the shape is large and well-proportioned.

[The Skilled Craftsman's Section]

In terms of carving techniques, Yang Yuxuan of the Qing Dynasty was renowned for his exquisite carving. Starting with him, Shoushan stone carving gradually matured from its initial rudimentary stage, making him widely regarded as the pioneer of this craft. During the Republic of China era, Lin Qingqing was particularly skilled in a shallow relief technique called "boyi," applying painting techniques to stone and combining carving and painting. He could design patterns based on the stone's natural shape and color. It is this craft, passed down through generations, that has transformed seals from mere tools in a study into works of art that integrate carving, stone material, and artistic conception.

Oval seal with cloud and dragon knob made by Yang Yuxuan, 3.9×1.9×6.2cm

Yang Yuxuan made an oval seal with a cloud and dragon knob made of Shoushan stone.

Yang Yuxuan made an oval seal with a cloud and dragon knob made of Shoushan stone.

From the late Ming Dynasty to the end of the Qing Dynasty, there were very few Shoushan stone carvers whose names were recorded. At that time, carving was usually regarded as an auxiliary decoration of seals. In the art circle where literati taste was the mainstream, the identity and contributions of carving craftsmen often did not receive the attention and importance they deserved.

Yang Yuxuan, who is revered as the "founding father" of Shoushan stone carving, is one of the few recognized masters of his generation. Even the scholar Zhou Liangong once praised him.

This "Shoushan Stone Cloud and Dragon Knob Oval Seal" perfectly showcases Yang Yuxuan's comprehensive skills. The knob at the top of the seal depicts a vivid scene of dragons playing in the clouds and water; the sides of the seal are carved in shallow relief (thin relief) to depict the patterns of seawater and boulders. The entire seal is a cohesive whole from top to bottom, clearly a carefully considered layout. The composition is varied in density and sparseness, expansion and contraction, making it a truly ingenious work.

Lin Qingqing's Shoushan deer-eye stone seal with a relief design of magpies on eyebrows, measuring 4.4×2.8×6.2cm.

Lin Qingqing's Shoushan Deer Eye Stone Seal with Relief Design of Magpies on Eyebrows

In Shoushan stone carving, "thin relief" is a very unique technique. This shallow relief carving was pioneered by Yang Yuxuan, Zhou Shangjun, and others. In the late Qing Dynasty, Lin Qingqing further refined it by using his skillful knife work to bring the artistic conception of literati painting onto the stone. He emphasized composing the design according to the shape and color of the stone, cleverly avoiding the flaws and imperfections in the stone, thus elevating thin relief to a true artistic level.

For example, in his Shoushan deer-eye stone seal with a bas-relief design of magpies on plum blossoms, he cleverly used the color variations of the stone to outline the rocks and plum branches. A touch of dark stone skin perfectly colored the old plum branches, creating a clear sense of depth in the picture. His skillful use of color was truly masterful.

Looking back at these small seals today, they are not only a condensation of the lingering charm of metal and stone, but also a microcosm of the character of literati. Just as Wu Changshuo once wrote in a couplet: "Eating the strength of metal and stone, nourishing the heart of grass and trees." Where the blade strikes, reason and emotion arise together; a single seal is enough to observe the heart and the world.

Auction Information

Qingning – The Art of Seal Carving

Preview Dates: November 5-7; Guardian Customer Day: November 8

Auction time: November 9th, Lot 1571-1870, 15:00

Auction Location: Hall B, B1 Floor, Guardian Art Center, Beijing

The Essence of Seal Carving: Important Seal Stones and Engravings from the Yanghetang Collection

Preview Dates: November 5-7; Guardian Customer Day: November 8

Auction Time: November 9th, Lot 1871-1928, 14:00

Auction Location: Hall B, B1 Floor, Guardian Art Center