Recently, the book "Use and Amusement - Secular Paintings of Qing Dynasty Events", written by the late American scholar Gao Juhan and translated by Yang Duo, was published by Life, Reading and New Knowledge. Through the visual research and style analysis of the secular paintings in the Sheng and Qing Dynasties, this book shows how the secular works in Jiangsu absorbed Western techniques, integrated the painting styles of the Northern and Southern schools, and created new painting methods and procedures. Peng Mei News hereby publishes the chapter "Using Western Factors in Jiangnan Urban Paintings" in this book.

In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, the semi-western painting styles used by artists active in cities in the south of the Yangtze River took on various forms. These forms are not different aspects of a single, self-contained art-historical phenomenon, on the contrary, they are derived from independent and diverse choices, the only thing in common is that the painter draws from foreign stylistic elements and visual techniques Resources useful for its creation. In order to illustrate this observation, some paintings from the Ming and Qing dynasties from Suzhou, Nanjing, and Yangzhou are introduced below. These painters belong to different types, not all of them are secular or workshop painters, and also include some related to the current discussion. Landscape painter.

Suzhou

I have had a lot of discussions about the various techniques used by some Suzhou painters in the Ming season to adopt elements of Western style, especially the painter Zhang Hong (1577-about 1652). Through the method of image comparison, I hope that most readers will be convinced of my point of view. For example, I cite Zhang Hong's "Ten Scenes of Yuezhong" in 1693 or "Zhiyuan Tu" in 1652. Compare with the copperplate illustrations in "Civitates Orbis Terrarum" (Civitates Orbis Terrarum) compiled by Braun and Hogenberg, who were already familiar to Chinese painters during this period. Related discussions and pictures are omitted here.

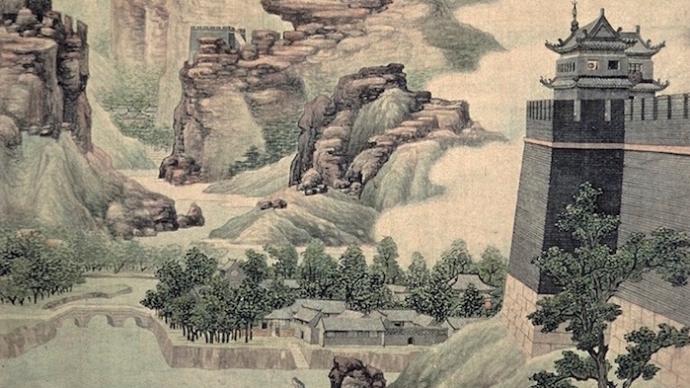

Figure 1: Suzhou Print (or New Year's Picture), 1743, color on wood, 98.2 cm × 53.5 cm, British Museum

The Western-style paintings written by Zhang Hong and some other painters in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties have pioneered the popular urban panorama color woodcut prints in Suzhou. Many of these urban panorama prints representing Suzhou and other towns were made in the 1730s and 1740s. . The exoticism of these prints can only be matched by very few paintings of the same period. The creators of the prints obviously had commercial considerations in adopting the exotic style, but at the same time, it was also to show their excellent skills, and some even stated in the inscription that the painting used Western painting methods. Paintings for tourists and local residents depicting lakes and mountains in and out of Suzhou have been the specialty of Suzhou painters since at least the 16th century. However, throughout the dynasties, the pictures produced for the general public have always coexisted with the works of famous literati painters depicting cityscapes and landmarks. Of course, it is the latter type of paintings that are mostly preserved in China, and the woodcut prints of the 18th century that have survived to this day are mostly hidden in Japan and other overseas countries. The designers of Suzhou prints are just like Ukiyo-e woodcutters. As long as they can bring freshness to the picture and enhance the commercial value of the work, they are willing to accept (the painting critics at that time may use the word "shameless") whatever they can get. method.

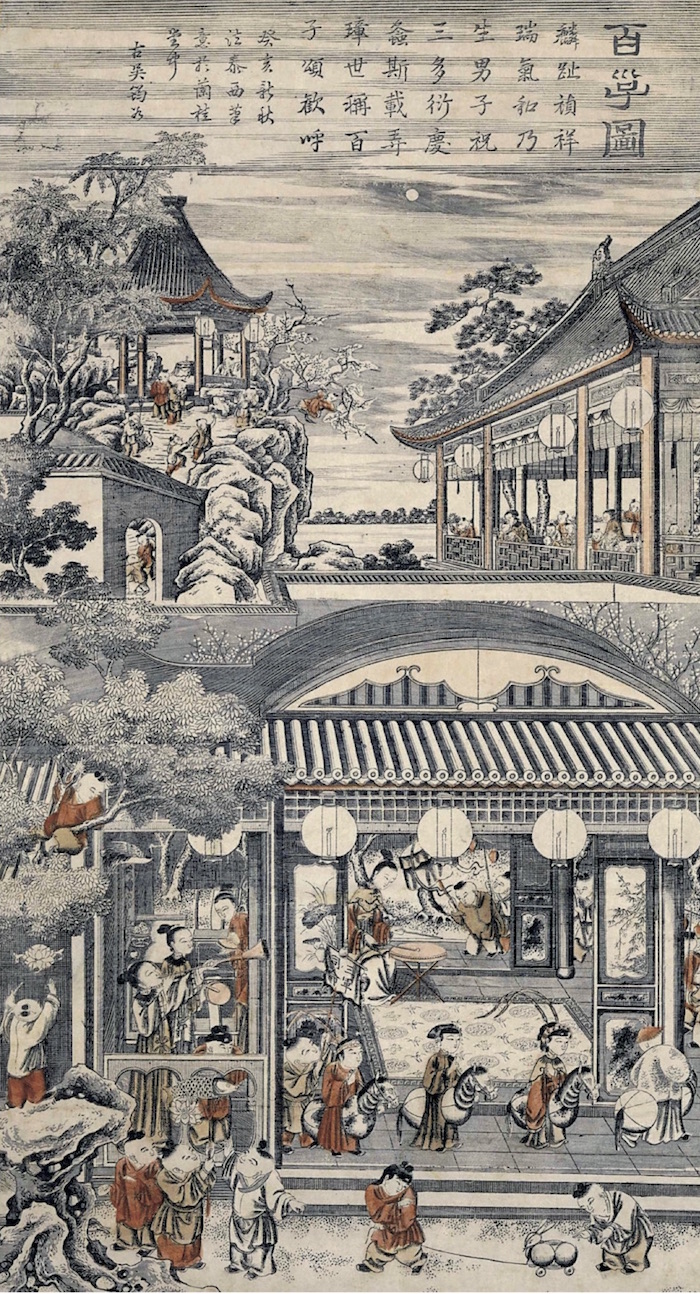

Figure 2: Woodcut prints of Suzhou woodcut "Liantang Xingle", two pieces can be combined into a single composition, one 74.6 cm × 56.3 cm, the other 73.6 cm × 56 cm, Umi-Mori Art Museum, Japan Museum, Hiroshima, Japan)

The Western techniques of visual illusion used in some woodcuts are more certain and intense than those used in all paintings (with a few exceptions): strong chiaroscuro, shadows cast by figures on the ground, or At the same time Japanese uki'e (uki'e) followed the same strict linear perspective (Chinese prints are even the main source of linear perspective for Japanese uki'e) (Figs. 1 and 2). Such woodcut prints are sometimes viewed with a special diorama, and the monocular lens on the diorama box can often enhance the depth of the visual illusion of the picture. Although the vanishing point linear perspective originating from Italy is more suitable for creating visual illusions, when used in the context of Chinese painting, it has a sense of eccentricity and abruptness. Therefore, Chinese painters outside the court painting academy wisely avoided the use of this foreign linear perspective, at least not in such paintings that have been handed down.Nanjing and Jiading

Regarding the influence of Western painting factors on the painting circle in Nanjing, we can start with two painters—Wu Bin (active in 1573-about 1625), a late Ming painter, and Zeng Jing, the leading pictorial painter of the late Ming Dynasty. Both painters started their painting careers in Putian, a coastal city in Fujian, not far from the prosperous port city of Quanzhou, which had been exposed to imported Western paintings since the 16th century due to trade with Portugal. The early painting careers of the two painters of whales must have also been influenced by these Western paintings. Although I have no intention of discussing the reference of late Ming portrait paintings to Western painting factors, it should be noted that the amazing revival of portrait painting during this period was not established as a lively and popular art form. To a large extent, it is inseparable from the nourishment of heterogeneous cultures and the seductive effects created by Western painting. As a Chinese critic at the time put it, the new painting technique allowed the portraits in the paintings to be “like a mirror,” and this observation is particularly applicable to Zeng Jing’s paintings.

Nanjing is an important missionary point for the Jesuits, so the Nanjing painting circle can better reflect the influence of foreign art. The paintings of the so-called "Eight Schools of Jinling" (a group of landscape painters active in the early Qing Dynasty) frequently appeared in the motifs and composition techniques of Western painting, including the effect of light and shadow illusion, the depth of field effect on the plane layer by layer, the clear horizontal plane, and the The boats and small bridges with the effect of perspective shortening, the interior space of the house is clearly readable. Fan Qi's hand scroll, now in the Berlin Museum, vividly embodies the artist's borrowing of Western techniques—horizontal short lines are used to contrast the lake surface with light and shadow effects, and the sailboats at the line between the water and the sky are cut off by thin horizontal lines. The effect of this horizontal plane can be found in a very similar illustration in Nadal's book Declare the Walks of Christ, and may even be derived from Nadal's book. This book had considerable influence in China at that time, so Fan Qi's hand scrolls were probably derived from Nadal's copperplate illustrations. The other painters of the Nanjing School of Painting—Zou Zhe, Gao Cen, Wu Hong, and Ye Xin—the westernized quality in their paintings is not so obvious at a glance, but it is also obvious.

Gong Xian's works

In terms of borrowing Western styles and imagery, the Nanjing masters of painting, Gong Xian (about 1619-1689), were the most innovative and created a mysterious "real" world scene, but as Gong Xian himself said, in the painting, The world is really a place that no one can go to. These paintings by Gong Xian and others are the most impressive masterpieces in the early Qing Dynasty paintings, and they are also another successful example of the perfect fusion of Chinese and foreign painting factors. The skill of these painters in combining Chinese and Western painting methods is exquisite, and unless these Chinese landscape paintings are side-by-side with those Western copperplate engravings that are more or less inspiring, it would be difficult for the viewer to realize that these paintings are not purely rooted in Chinese painting traditions. For example, in his 1923 monograph on Chinese painting, Arthur Waley memorably called Gong Xian "the most original painter in early Qing painting circles", a number of French painters in the late 19th century. Critics have also found the sunset effect or the abrupt depth of field effect in some of Hokusai's Mount Fuji prints to be peculiarly alluring. For these Western audiences, they may not realize that, compared with other Chinese painters' paintings, Gong Xian's landscape paintings are more likely to make them feel close, because the effect of Gong Xian's paintings is borrowed from their own. painting tradition, which explains why they find Gong Xian's painting familiar and easy to understand.

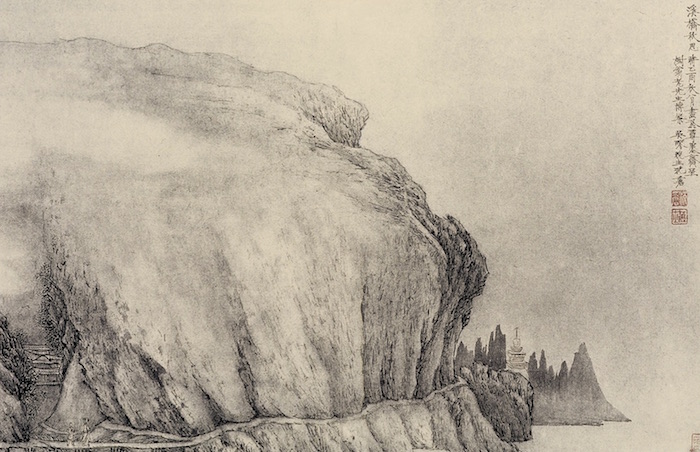

Figure 3: Album of Shen Cang's "Autumn Thoughts on the Bridge of the Stream", ink on paper, 29.8 cm × 45.2 cm, Ostasiatische Knstsammlung Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin inv.no.1960-5

The workshop was located in Jiading, a small town about 20 miles southeast of Shanghai. The painter Shen Cang (active in 1697-1714) was only a well-known painter. The records of the local chronicle mention that he once went to the capital in Beijing, where he met "people from the west", and the Western painting techniques used in his paintings may have been learned from these people from the west. If this conjecture is correct, Shen Cang does not belong to the Jiangnan artist who took the Western painting model from Kyoto as discussed above. Taking Shen Cang's Autumn Reflections on the Bridge in 1705 (Fig. 3) as an example, there are many elements of Western painting in the painting: a huge cliff with a rather specific and quantitative shape, and at the bottom left of the picture, under the towering cliff, a pair of small figures are slow. Slowly crossing the stream bridge, that is, the scribes and their book boys. The buildings in the valley behind the two figures and the pagoda-like pavilions beside the mountain road on the right side of the picture (and the needle-shaped peaks echoing them in the distance) show the meticulous style and skill of Shen Cang pavilion painting. The dignified soil blocks occupying the main composition in the painting have uniform highlights and shadows, and clouds and mists pass through the middle. Such compositions have been seen in Wu Bin and Gong Xian's landscape paintings earlier in the era. The reason why these two artists have such characteristics is that in addition to borrowing foreign styles, they also inherited the tradition of the giant mountains and rivers in the Northern Song Dynasty.

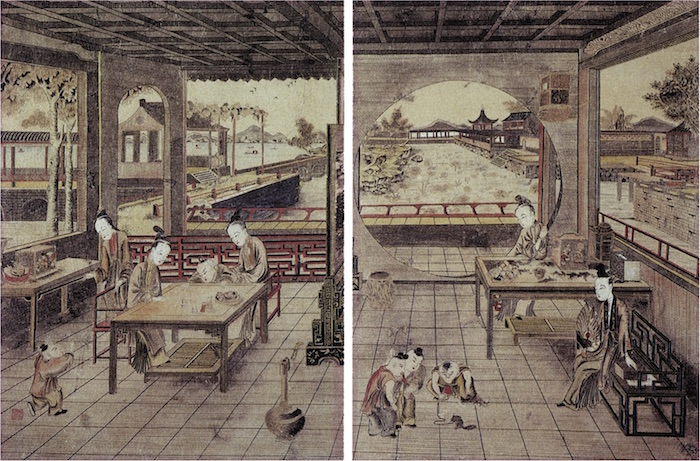

Fig. 4: Album of Shi Daocun (Shizhuang), from "Eight Views from the Roof" 1706, Sotheby's auction catalogue (New York, June 1, 72) See also Sotheby's Hong Kong", Fine Chinese Paintings from the Currier Collection, "May 1, 2000, no. 109. The atlas lists the painting date as 1766 and the painter's death year as 1792

Fig. 5: Album of Shi Daocun (Shizhuang), from Eight Views from the Roof, 1706, ink and colour on silk, 36.2 cm x 28 cm, Sotheby's auction catalogue (New York, June 1, 72) See also Sotheby's Hong Kong, “, Fine Chinese Paintings from the Currier Collection,” May 1, 2000, no. 109. The atlas lists the painting date as 1766 and the painter's death year as 1792

From the end of the 17th century to the beginning of the 18th century, Yangzhou's wealth and cultural attractiveness increased day by day. Gong Xian and other artists from Nanjing, Huizhou and other parts of the south of the Yangtze River all moved to Yangzhou and became active painters here. Another painter who moved from Nanjing to Yangzhou at a later time was Shi Daocun (Shizhuang). His album "Eight Views of the Tiantai" has the Jiazi year, which corresponds to 1706. This album is the most extreme of the semi-western techniques used in landscape paintings. A striking example (Figures 4, 5). This album, like the Suzhou civic prints, should even be considered a hybrid style, as the artist combined Chinese painting traditions with Western visual illusions in strange and eccentric ways. The artist probably wanted to use this to create an effect of alienation, in order to convey the splendid wonders of Tiantai Mountain beyond the world.All of the above are landscape paintings, and these paintings are introduced here only to show that the phenomena tracked in this book are ubiquitous. The figure painting in the Nanjing painting circle in the early Qing Dynasty seems to have not yet formed a climate, the only exception is the painter Zhou who came from the vicinity of Jiangning and was active in Nanjing. Zhou is known for his dragon paintings, but he is also good at figures and pommel horses. Most of his paintings feature prominent chiaroscuro effects, but are otherwise fairly conventional.

Yangzhou

Yangzhou became the center of painting later than other Jiangnan cities. From the end of the 17th century, the wealth and art patron resources of other Jiangnan cities, especially those in southern Anhui, gradually moved to Yangzhou, and this momentum continued until the end of the 18th century. What attracts artists from all over the world to Yangzhou is its rich art sponsorship resources. The wealthy big salt merchants and their mountain museums and cultural associations are undoubtedly the most important funding centers. In addition, sponsorship also comes from a large number of wealthy urban elites and middle class. class. There are merchants, officials, bartenders, actors, successful artists and other people mixed in the city of Yangzhou. If we can temporarily avoid the so-called Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou and the works of painters with similar styles, we will find that there are still some painters or painters in Yangzhou. More or less devoted to the westernized tendencies of painting. Below, we will choose to discuss a few of them.

Figure 6: Shen Quan, Drinking Cow by the Stream, 1740, 12-open book of animals and birds, ink and color on silk, 20.6 cm x 31 cm, gift of Marilyn and Roy Papp, Phoenix Art Museum

First of all, Yuan Jiang, a professional painter who was active in Yangzhou during the Kangyong period, and Li Yin, Yuan Yao's son or nephew Yuan Yao, who were very close to him, all took it as their job to transform the elements of Western style and make them useful, and their paintings also They are all based on the palace landscape of the "academic body" in the Song Dynasty. Their contemporaries Xiao Chen (about 1680-1710) and Wang Yun (about 1652-1735) were professional painters active in Yangzhou. Their works adopted the traditional style of exquisite workmanship, but mixed with Visual illusion has somewhat enhanced the vitality of the picture. We will pass by these two painters. But they are representative of many, many painters of their kind. Zhejiang painter Shen Quan (Shen Nanping, 1682-circa 1760), who specializes in landscapes, flowers, birds, and animals, was originally from Wuxing. In his later years, he traveled east to Japan in 1733. After living for two years, he returned to China and has been active in Yangzhou. Many of his paintings were circulated in Japan and were highly respected by the Japanese. He was the only respected Chinese painter who lived in Japan before the 19th century. Even during his time in Japan, his activities were restricted and he could not leave Nagasaki, the trading port. In Nagasaki, he taught painting to apprentices. His painting style was based on traditional Chinese painting, but he was also deeply influenced by the newly imported Western painting concepts. More than one recent scholar has attempted to downplay or even deny the Westernized visual illusion in Shen's paintings. However, this type of research has once again gone in the wrong direction, and will ultimately find nothing, because even a cursory review of Shen Quan's paintings will reveal that the birds and beasts in the paintings, although generally based on the Song and Ming courtyard paintings, are But at the same time, it also reveals Shen Quan's unique creation: the prominent light-receiving surface is rendered with a unique Western style, and the way of dealing with light, shadow and space in the depiction of natural scenery is obviously not part of the Chinese painting tradition. An excellent example is Shen's 1740 Landscape Animals and Birds Book, of which the most representative one is the one showing the cow drinking by the stream (Figure 6). Shen Quan's inscription on this album calls this painting "a small scale imitating the people of the Song Dynasty." However, the painters of the Song Dynasty would never create such a visual illusion when smearing animals, nor would they create light and shadow in the treatment of river banks and tree trunks. Flowing light and dark effects. The cultured audience that these paintings are aimed at, mostly have positive reviews of these paintings, which incorporate Western styles (a good testament to the success of these artists and the popularity of this hybrid style). Recognizing this also helps to understand the indifference of the descendants of authentic Shanshui painting to this type of painting from a correct perspective. Not only that, but it also inhibits our urge to "protect" painters by denying them the borrowing of Western art, as if borrowing is a form of borrowing. a disgrace to the artist.

Yu Zhiding's Figure Paintings

Some of the figure paintings of Yu Zhiding, the leader of figure painting in the early Qing Dynasty, inherited Zeng Jing's practice and used Western visual illusion techniques in large numbers. But another part of the works is completely from the Chinese painting tradition, without any foreign influence. As a multi-talented painting master, Yu Zhiding seems to be able to move freely between various artistic styles and painting types.

Gao Juhan, translated by Yang Duo, "Use and Amusement: Secular Paintings of the Great Qing Dynasty", Life·Reading·Xinzhi Sanlian Publishing House

(This article is excerpted from the book Life·Reading·Xinzhi Sanlian Publishing, written by Gao Juhan and translated by Yang Duo, "Use and Amusement: Secular Paintings of the Great Qing Dynasty", the original title is "The Taking of Western Factors in Jiangnan Urban Paintings". use")