Jean-Antoine Watteau (circa 1684–1721) was one of the most influential and prolific artists of the 18th-century French Rococo era. His masterful fusion of genre and mythology with the lightheartedness of Rococo art created a new genre, the "banquet," which influenced generations of French artists.

Watteau often depicted scenes of opulence and elegance, yet these were tinged with a melancholy that evoked the trivialities and frustrations of life. Currently on view at the British Museum (until September 14th), "Color and Line: Drawings by Jean-Antoine Watteau" is an exhibition showcasing his drawings alongside his paintings. Within the chaotic cacophony of lines, one can discern the earliest and freshest bursts of creativity.

Rosalba Carriera, Portrait of Antoine Watteau, circa 1721

Antoine Watteau, Woman in a Striped Dress, 1716–1718, British Museum

In 1712, Watteau was accepted as a member of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. He only needed to submit a single work to confirm his appointment. However, this work ultimately took him five years to complete, during which time the Academy's administrators pressed him ever more harshly. For some artists, this delay might symbolize the slow brewing of genius, but for Watteau, it was likely simply procrastination.

Antoine Watteau, "Setting for Cythera", oil on canvas, 129x194 cm, 1717, now in the Louvre Museum, France

In fact, "The Embarkation for Cythera" (1717, now in the Louvre) was completed in such haste that the paint appears to have been wet when it was handed in. During this period, he continued to sketch. When Watteau died in 1721 (from tuberculosis at the age of 37), he left behind thousands of sketches, all vibrant with black, red, and white lines, a technique derived from Netherlandish art called "trois crayons."

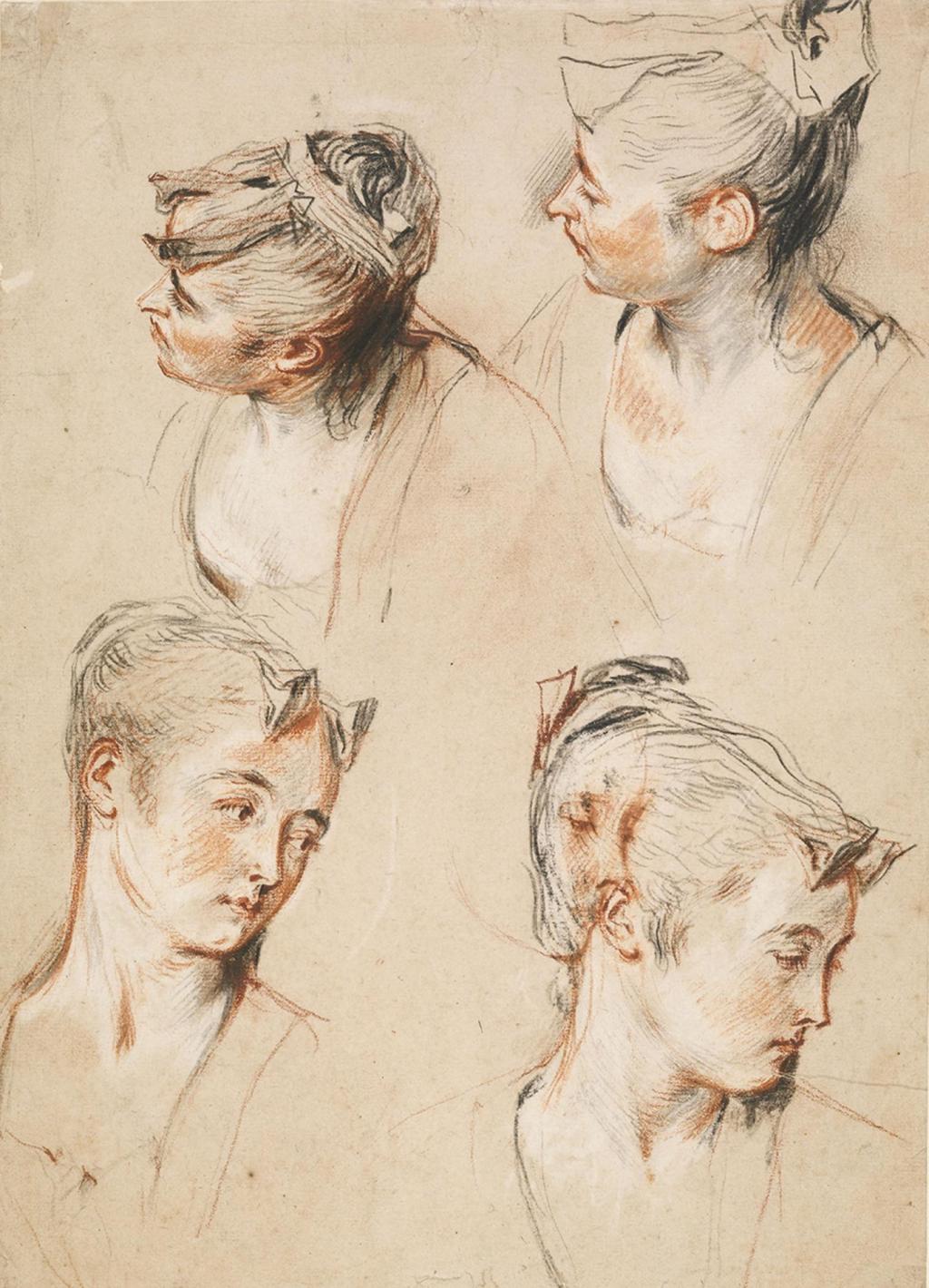

Antoine Watteau, Five Studies of Female Heads, 1716–1717, British Museum

As his contemporaries noted, sketching was his favorite form of creation, bringing him "a pleasure far greater than that of a finished painting." "Color and Line: Drawings by Jean-Antoine Watteau," currently on display at the British Museum in London, includes nearly every authentic Watteau drawing in the museum's collection. This is the first dedicated exhibition of Watteau drawings at the British Museum since 1980.

Obsession with sketching: a creation more pure than oil painting

Watteau's hometown of Valenciennes had been the cultural center of the Netherlands under the Spanish Habsburgs, but by 1700 the city had become part of France. The lack of skilled artists in the area led Watteau to Paris in 1702 to begin his true artistic training.

In 1709, at the age of 25, Watteau won second prize in the Prix de Rome competition held by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in Paris. But like all ambitious young artists of the time, he wanted to study in Rome, and perhaps his disappointment at missing out on first prize forced him to return home.

The early works in the exhibition, dating from the year he returned to his homeland, depict limber soldiers with graceful demeanor, including one drawn in red chalk holding a tray of rations like a snuffbox.

Antoine Watteau, Seated Woman, 1716–1717, British Museum

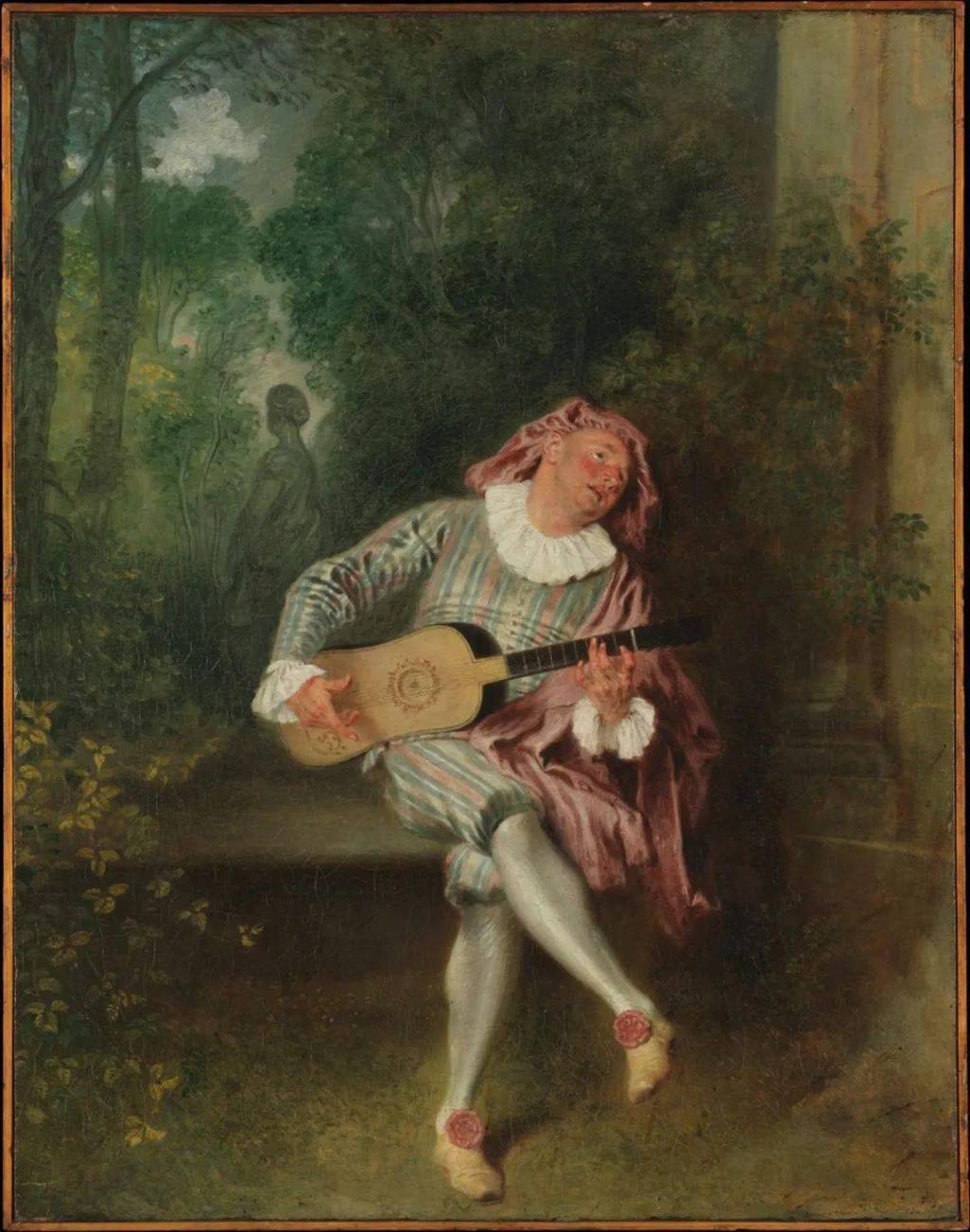

Upon returning to Paris, he also captured the "Savoyardes" (a term typically referring to impoverished people who migrated from the French Alps to Paris and other major cities to seek a living) who frequented the city during the harsh winters, their figures outlined in rough brown lines. A woman sits on a street corner, a wooden box beside her—a marmot, which she can display for a fee. Watteau, always fascinated by sartorial detail, depicts the "Savoyarde" with the same meticulous attention to detail as the sartorial attire of the upper classes, including her headscarf, cane, and thick shoes. Images of refined life, more familiar to contemporary audiences, abound throughout the exhibition: a young woman, dressed in a ruffled collar and riding cape from the previous century, sits leisurely on the grass; a guitarist gently plucks a string with slender fingers; and stacks of anonymous women, their faces painted with exquisite precision, their heads tilted toward an unseen object.

Antoine Watteau, Five Studies of Seated Women, c. 1714-1715, British Museum

In stark contrast to his procrastination on painting, Watteau's devotion to drawing seemed almost obsessive: his friend, the art dealer Edmé-François Gersaint, once described him as devoting nearly every spare moment to his pencil. Even so, what makes Watteau's drawings unique is perhaps not their quantity but his dedication to preserving them—at a time when many artists still viewed them as merely a transition to the higher goal of painting. Watteau's drawings were closely intertwined with his painting practice, with many figures and motifs directly transferred to the canvas: the devoted guitarist in the British Museum exhibition is dressed in pink in The Scale of Love (c. 1717–1718, now in the National Gallery) and in silver in Gallant Recreation (c. 1717–1720, at the Berlin Museum of Fine Arts).

Antoine Watteau, Two Studies of Men Playing Guitar and One Study of a Man's Right Arm, c. 1716, British Museum

Antoine Watteau, The Scales of Love, oil on canvas, 50.8×59.7cm, circa 1717-1718, now in the collection of the National Gallery, London

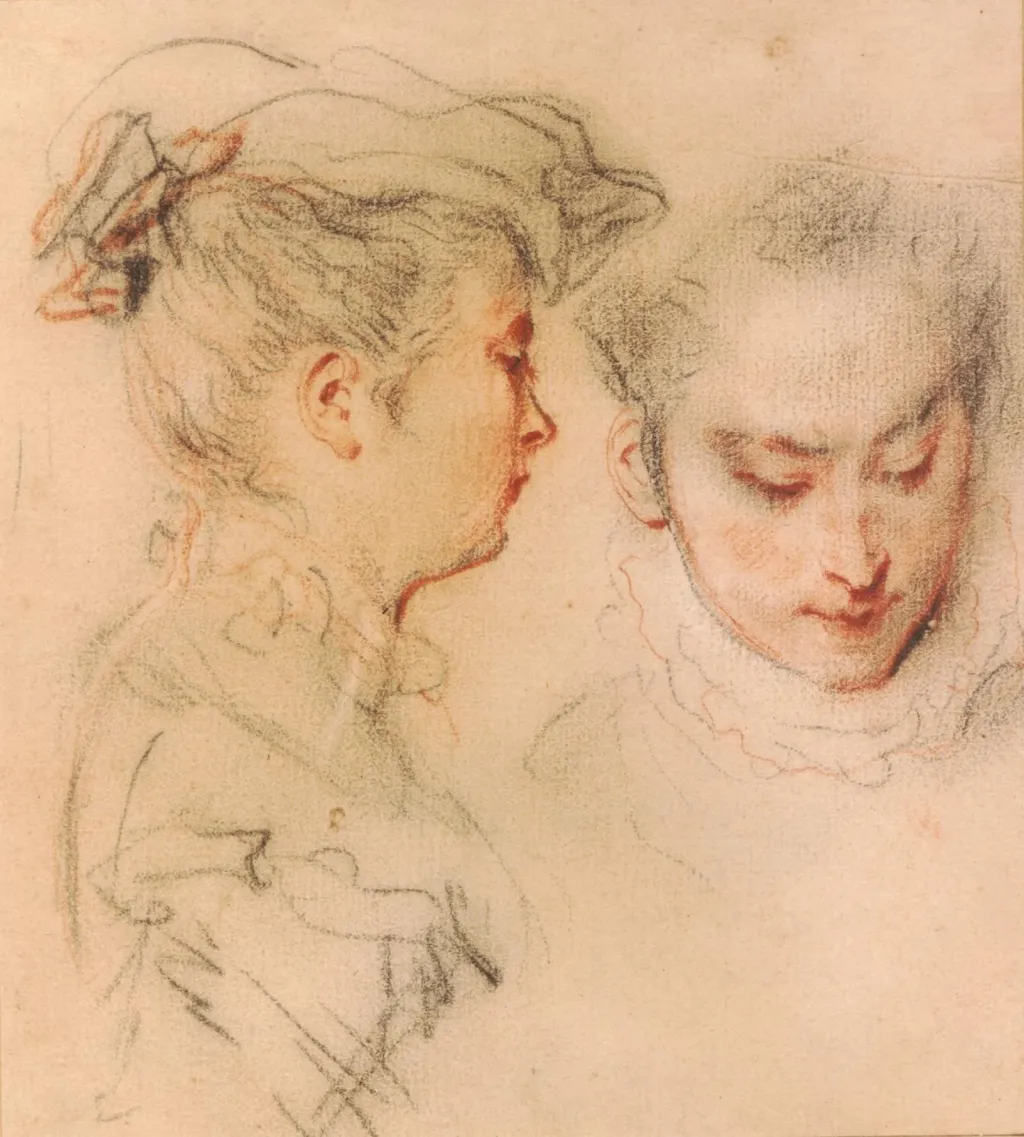

At the same time, Watteau effortlessly isolates and expands upon his figures, imbuing many of his drawings with an almost cinematic, fleeting quality that he could never fully recreate in his paintings. "Three Heads," for example, juxtaposes the same woman's face from three angles, as if we were watching her slowly turn. Here, the drawings are not merely preparatory to the painting; they are the first and freshest bursts of creativity, which Watteau felt were inevitably diminished when translated into oil painting.

Antoine Watteau, Two Studies of a Woman's Head, 1716–1717, British Museum

Years after painting a page in an apron, Watteau added the drooping head and shoulders of a woman, the rhythm of her skirt echoing the folds of the everyday linen—a dialogue between the artist and his earlier self. This recurrence often makes Watteau's dating difficult to pin down, but it also breeds countless flashes of wit.

Antoine Watteau, Two Studies of a Woman's Head, 1716–1717, British Museum

While Watteau's cherishment of his drawings was unusual at the time, it was not unique. As the art market developed in the early 18th century, collectors increasingly sought works on paper. Drawings were often cheaper than paintings and could be reproduced through counterproofs. In an era that prized spontaneity, drawings also offered a more direct insight into an artist's creative process.

Ultimately, this respect for the drawing became one of Watteau's most significant legacies. Shortly after his death, in 1728, Jean de Jullienne (French textile manufacturer, art collector, and amateur engraver) published his magnificent Figures de différents caractères (Figures of Various Figures), a two-volume collection of drawings dedicated entirely to Watteau's works on paper. Jullienne's choice to reproduce Watteau's works in vivid etchings (rather than the more rigid engravings) was virtually unprecedented at the time, a fitting tribute to the recently deceased artist's works on paper.

From "The Joy of Dance", see the texture of light

The Dulwich Picture Gallery in London houses Watteau's "The Joy of the Dance." While the painting is rich in subtle depictions, describing it solely through the lens of subject matter seems to miss its core. Is figurative painting truly "about" the subject it depicts? Often, the story or the subject serves only as a framework, allowing something more subtle to exist—like a dreamcatcher, capturing only the fleeting traces within, just as Baudelaire saw the flaming, floating butterflies in Watteau's painting: "There, countless noble souls / Like butterflies, blazing and wandering."

The pictorial quality of The Joy of the Ball is exceedingly difficult to capture. When Charles Robert Leslie (1794–1859) showed his copy to his friend John Constable, he remarked, "Yours looks colder than the original, which seems painted with honey, so round, so gentle, so soft, so wonderful... This elusive, exquisite quality would make even Rubens or Veronese seem vulgar." Many Watteau followers, including Nicolas Lancret (1690–1743), attempted to find a "formula," but all failed in the process.

What is this quality? Perhaps it has something to do with balance. While much is happening in this painting—whispers, approaches, embraces, rejections, music (especially heard by a dog)—there's no primary or secondary. The painting is filled with detail, but all distinctions are created by light, and wherever it shines, it seems temporary, not permanent. Light from the front left illuminates the folds of the skirt of the woman facing away from the viewer, the left calf of her partner, the wine glass and silverware, and the knee of a woman to the right.

Light is fair. While most of the figures in the painting appear upper-class, the spirit is democratic. Beneath the Veronese-esque turbaned man, standing behind the railing, are the black-clad musicians and guests, unlit yet still clearly visible. Viewed in isolation, this section of the painting almost evokes Sickert's theater paintings: as the light shifts, those grayish-brown shadows emerge.

At the back of the painting, in the dancer's line of sight, a fountain is depicted as a dazzling beam of light. Further away, tiny human figures appear. A closer look might reveal something as haunting as Giorgione's The Tempest. Like a translucent stage curtain, which can become opaque or transparent depending on the light, revealing deeper layers of the scene, this painting has no clear endpoint, but rather suggests there's always something more. Light can fall here or there.

Antoine Watteau, The Market at Besson, oil on canvas, 106.7 x 142.2 cm, circa 1733, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Antoine Watteau, "Metztin with the Guitar", oil on canvas, 55.2×43.2 cm, circa 1718–1720, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

When looking at Watteau's works, the "tone" and "texture" of the picture are more inspiring than the theme and story. The characters seem to emerge vaguely, like afterimages deep in memory, with a gentle power.