In 1534, the 59-year-old Michelangelo (1475-1564) left Florence for Rome, where he worked for nearly 30 years, painting "The Last Judgment" and other works.

In May 2024, the special exhibition "Michelangelo: The Last Thirty Years" will be displayed at the British Museum. The exhibition will display many drafts of paintings by Renaissance master Michelangelo, including the sketch of "The Last Judgment" and the newly restored draft of "Theophany", etc., to show the new chapter of his life and his life in the last thirty years of his life. Artistic creativity.

In 1534, Renaissance master Michelangelo Buonarroti was 59 years old and already the most famous artist in Europe. Michelangelo was proficient in the fields of sculpture, painting and architecture, and was also a talented amateur poet. In 1534, he was commissioned by Pope Clement VII to fresco "The Last Judgment" in the Sistine Chapel. When he returned to Rome from his native Florence, he had reason to think that he was ending a long and eventful career. But, as British Museum curator Sarah Vowles explores, it's an exciting new beginning.

In the 16th century, 60 was a respectable age. It was hard for Michelangelo to imagine that he would live another 30 years after returning to Rome. During the last three decades of his life, until his death at nearly 89, he was busier than ever. He used his expertise and imagination to complete demanding projects commissioned by the Pope. And it is his dynamic late artistic period that frames the exhibition "Michelangelo: The Last Thirty Years."

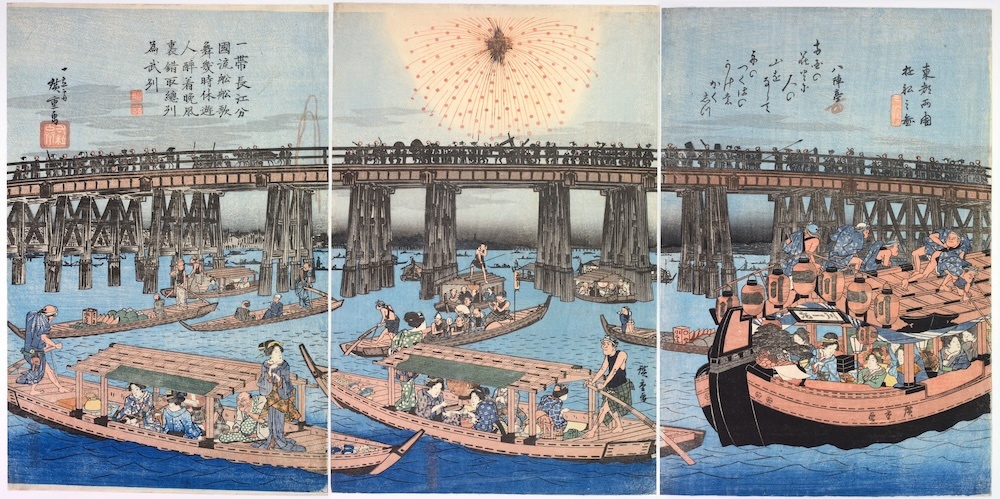

Michelangelo, sketch of The Last Judgment, black chalk on paper, circa 1534-36

Back to Rome

First of all, "The Last Judgment" was painted on the altar wall under the gorgeous dome of the Sistine Chapel. It was the ceiling fresco "Genesis" above it that helped Michelangelo become famous in his thirties. To create a mural, the artist must paint the image onto wet plaster, a day-by-day, careful process that requires extensive preparatory planning and a series of wonderful sketches, ranging from early dynamic composition designs to , to perfecting the study of characters and heads.

Michelangelo, sketch of The Last Judgment, black and red chalk on paper, circa 1534-36

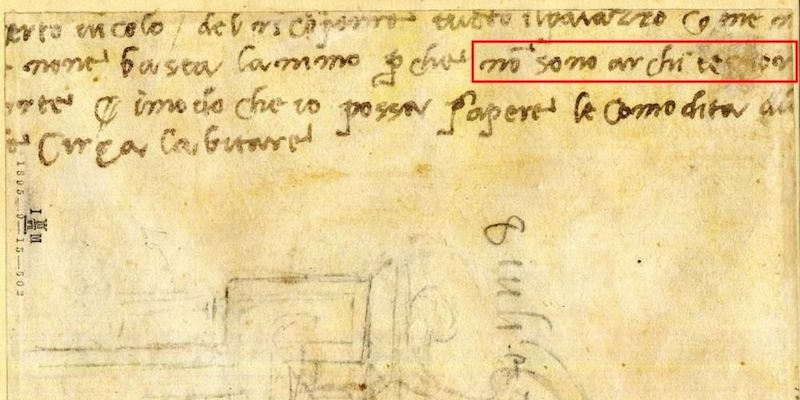

But this was not the end of the papal ambitions, nor was it the last project commissioned from Michelangelo. Next, there are two more frescoes in the adjacent Pauline Chapel. The Pauline Chapel is the Pope's private place of prayer. Next came the greatest and most challenging project of all: supervising the construction site of St Peter’s Basilica. There, the church at the heart of the Catholic world is rising from the ashes of ancient cathedrals. In the 1540s, Michelangelo vented his dissatisfaction in his research notes in the Pauline Chapel. "I'm not an architect," he complained. But his patrons did not listen to his complaints and during the last 20 years of his life he was involved in the construction of Palazzo Farnese, Porta and Piazza Campidoglio. del Campidoglio, and the iconic dome of St. Peter’s Basilica. Ultimately, his artistic vision was imprinted on the fabric of Renaissance Rome.

Michelangelo wrote in his scrawled notes "I am not an architect"

New results of cooperation

In the past, Michelangelo had always preferred to work alone. But now, due to failing health and old age, he has had to learn to adapt to working with others. He systematized a method of working that he had used sporadically in his youth and collaborated with a dedicated panel painter to meet the needs of his non-papal patrons. Michelangelo created the composition first, and then a painter, usually his main collaborator Marcello Venusti, translated the composition onto the canvas and added scenes and other details from his own imagination.

For example, Michelangelo's crescent-shaped form for The Purification of the Temple was adapted by Venusti into an upright painting, placing the figures in striking, In Solomonic columns with twisted axes. This is reminiscent not only of the Temple in Jerusalem, but also of St. Peter's Basilica itself. This collaborative system was a huge success: it enabled patrons to own a work of art that had been conceived, authorized and approved by Michelangelo, who was often overworked for many years, and completed in collaboration with others.

Michelangelo, Christ driving the money-changers from the Temple—, paper, black chalk, circa 1550

Marcello Venusti, The Purification of the Temple, oil on wood, circa 1550

Although Venusti seems to have been Michelangelo's favorite collaborator, Michelangelo also designed or supplied his own works for other artists. The most striking is Epifania, a full-scale sketch. The sketch appears to have been left in Michelangelo's studio after the commission for it failed. This huge painting, more than two meters high and nearly two meters wide, was given to Michelangelo's assistant Ascanio Condivi. The gift may have been in gratitude for Condivi's flattering biography of Michelangelo in 1553. At that time, Condivi himself was at the beginning of his artistic career and needed a major breakthrough, and it was a great honor for him to obtain Michelangelo's design.

Michelangelo, Epifania, paper, black chalk, 1550-53

Condivi's Theophany painting is now in the collection of Casa Buonarroti in Florence, a museum established in Michelangelo's former residence. With the support of the British Museum, the museum carried out restoration and conservation work specifically for this purpose. In the exhibition, the work will be displayed alongside Michelangelo’s drawings of the subject. This is also the first time the two works have been reunited since the 16th century.

personal hobby

The exhibition at the British Museum is not limited to Michelangelo alone, but attempts to give visitors a better understanding of Michelangelo himself. Michelangelo certainly had his moments of rudeness and criticism, and he was easily irritated, as seen in his letters to his long-suffering nephew Leonardo. At the same time, he also has an affectionate and tender side.

Michelangelo, The Fall of Phaeton, black chalk on paper, circa 1533

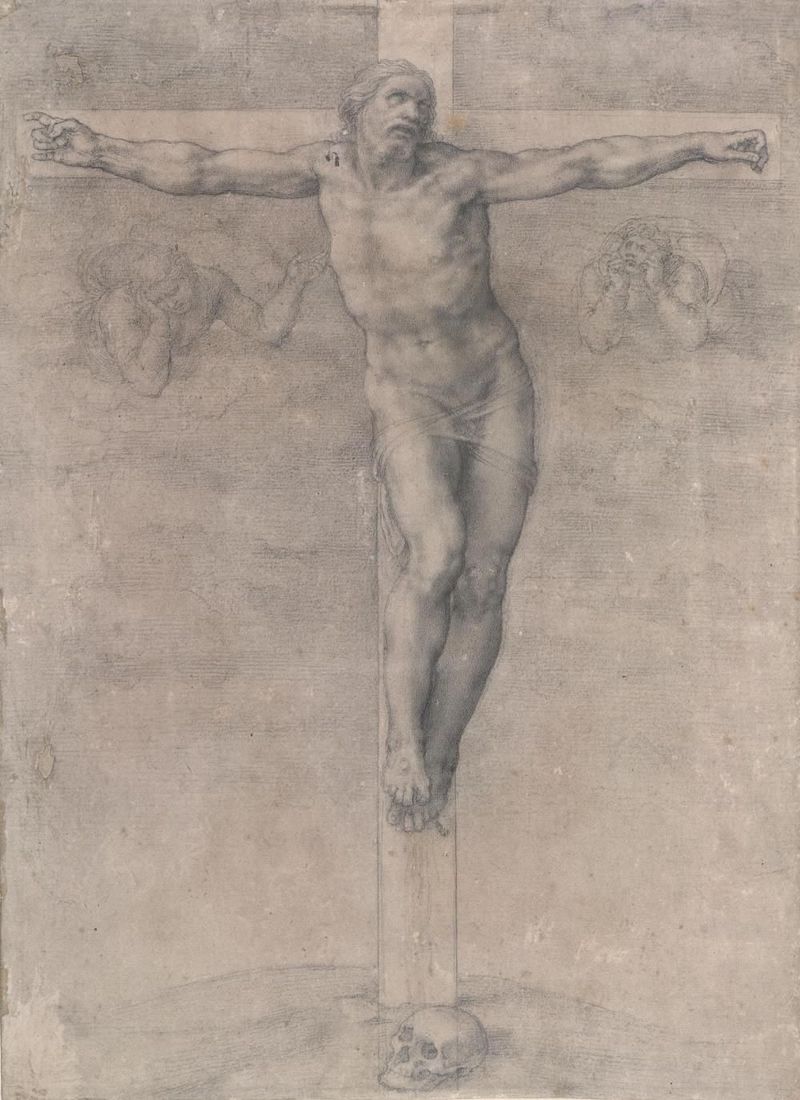

The exhibition tells the story of two important friendships between Michelangelo and the Roman aristocrat Tommaso de' Cavalieri and the aristocratic poet Vittoria Colonna in his later years. These two friendships led to the creation of poetry and beautiful artistic designs. These works are based on their common interests: for example, Tommaso's works are exquisite mythological allegories, which prompted Michelangelo to create "The Fall of Phaeton" (The Fall of Phaeton), providing young people with a moral guidance; Vittoria's focus on religious imagery led him to create "Christ on the Cross," which drew on relatable imagery from the Reformation to evoke the tragedy of Christ's death. and victory, and his redemption of mankind.

Michelangelo, Christ on the Cross, black chalk on paper, circa 1538-41

depict faith

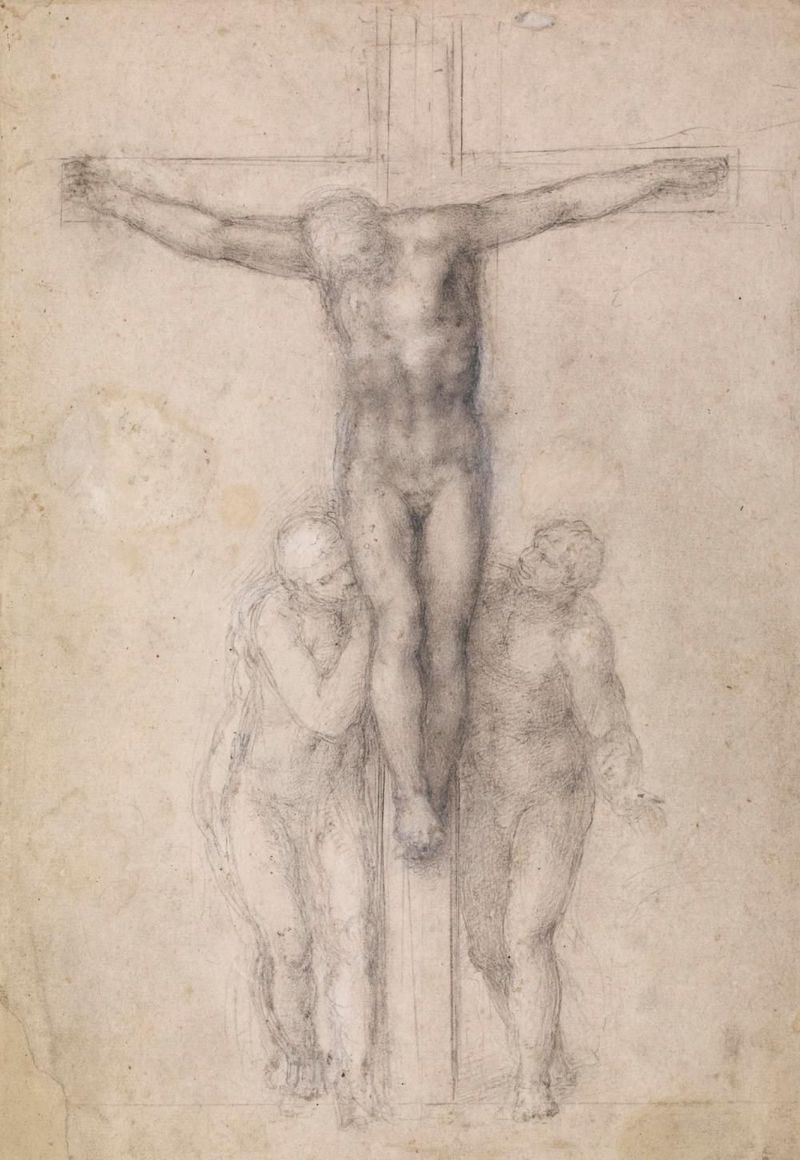

Michelangelo was a devout Catholic. As he grew older, he became more and more concerned about the state of his soul. Through his nephew Leonardo, he sent large sums of money to Florence for charity. Both his art and poetry reveal a deep and intimate concern with issues of redemption. The intensity of his concerns becomes even more understandable if we consider the times in which he lived. The Reformation in Northern Europe, which challenged many aspects of traditional Catholic teaching, had a huge impact on Rome, and the Catholic Church was trying to respond. One of the most moving examples of Michelangelo's personal exploration of faith is a group of crucifixion paintings. This group of works may be a long-term creation in his last 10 years, showing that the aging artist used the act of painting as a A means of spiritual meditation. He uses variations on a single theme to explore his feelings about death, sacrifice, faith, and the prospect of redemption.

Michelangelo, Christ on the Cross between the Virgin and St John, black chalk and white lead on paper, circa 1555-64

Usually, people's impressions of Michelangelo mainly focus on the classic works of his youth: for example, "David", or the ceiling frescoes of the Sistine Chapel ("Genesis"). This exhibition hopes to introduce people to Michelangelo's creative career between the ages of 59 and 89, as well as the extraordinary changes and creativity during it, and celebrate his continued creativity and determination in the face of aging. By drawing on Michelangelo's own voice from letters, poems, and other documents. At the same time, taking into account his friendship, as well as his own very human doubts and foibles, it is hoped that viewers will have the opportunity to appreciate Michelangelo's work and understand the man from a different, more intimate perspective.

The exhibition "Michelangelo: The Last Thirty Years" will be on view from May 2 to July 28.

(This article is compiled from the official website of the British Museum, the author Sarah Vowles is the exhibition curator)