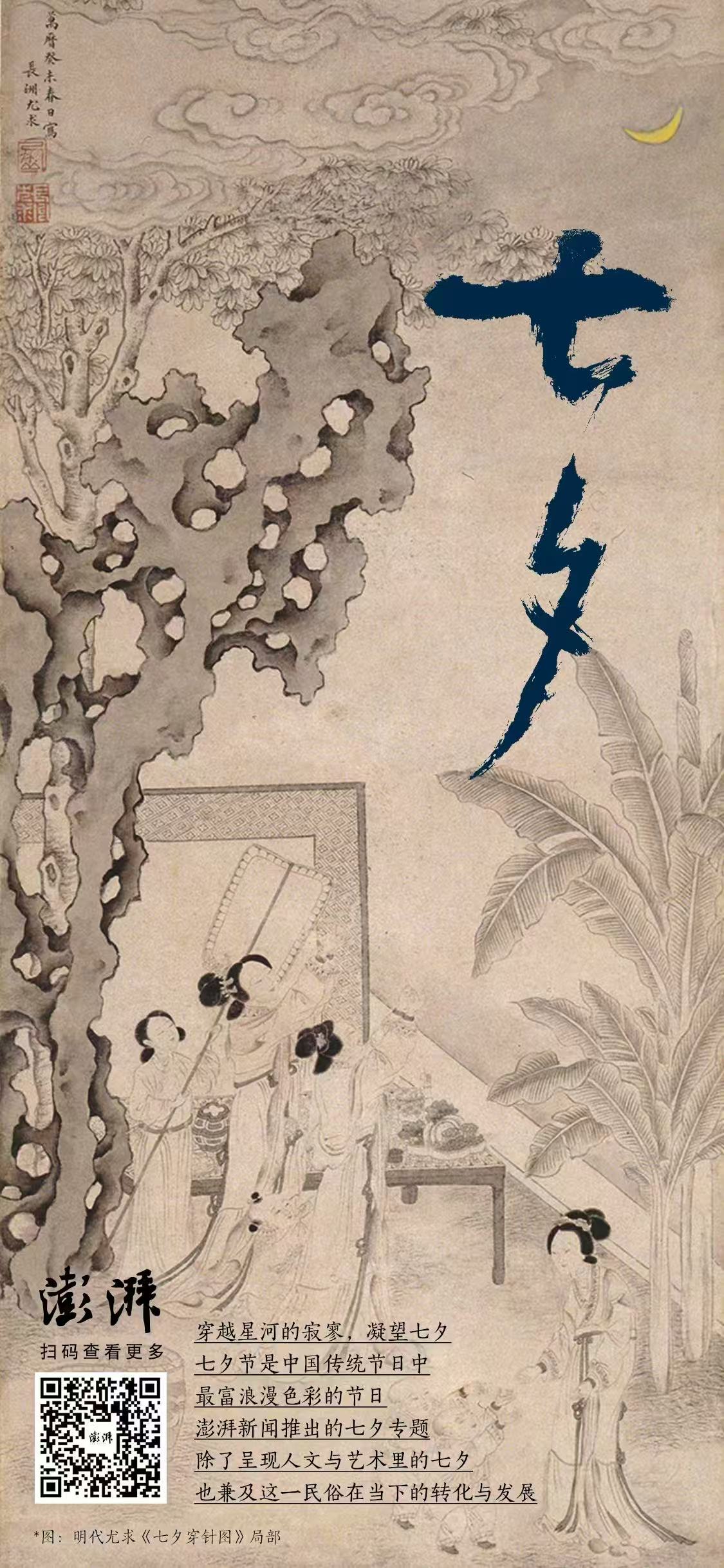

"The distant Altair, the bright Vega." Every year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, the traditional Chinese festival Qixi Festival (Chinese Valentine's Day) originates from the beautiful legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl. This legend lives on in poetry, songs, and oral traditions, and has been embodied by skilled artisans in various forms, including bronze, ceramics, silk fabrics, and stone carvings. Whether gazing at the pristine star deities in Nanyang Han Dynasty paintings or contemplating the meeting of magpies on the Magpie Bridge depicted in Ming and Qing Dynasty artifacts, it feels like witnessing a cultural dialogue spanning millennia: while the material mediums and artistic styles have evolved, the people's admiration for faithful love and their yearning for a better life remain unwavering.

The legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, one of China's most famous folk love stories, traces its origins to the astrological description in the "Book of Songs" (Xiaoya, Dadong): "On tiptoe, the weaver girl weaves, weaving all day long." Over two thousand years of evolution, this theme has not only become a key theme in literature and art, but has also left a rich and diverse legacy in various cultural relics.

Together, these cultural relics construct the physical memory of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl legend, giving the ethereal myth a tangible reality and leaving an enduring, physical imprint on earth of the eternal love that transcends the galaxy. As Li Shangyin, in his Tang Dynasty poem "The Seventh Night of the Seventh Month," wrote: "Perhaps the immortals, delighting in separation, have taught us to meet at a distant time. By the azure Milky Way, we must wait for the golden wind and jade dew." Cultural relics are precisely the golden wind and jade dew that brought this encounter between human and immortal, a tangible witness to that time.

Han Dynasty Portraits: Early Creation of Star God Images

The legend of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl and the Qixi Festival (Chinese Valentine's Day) originates from astronomical theories. Records of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl exist as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty. The Han Dynasty was a crucial period for the formation of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl legend, with related representations primarily found in stone reliefs and murals.

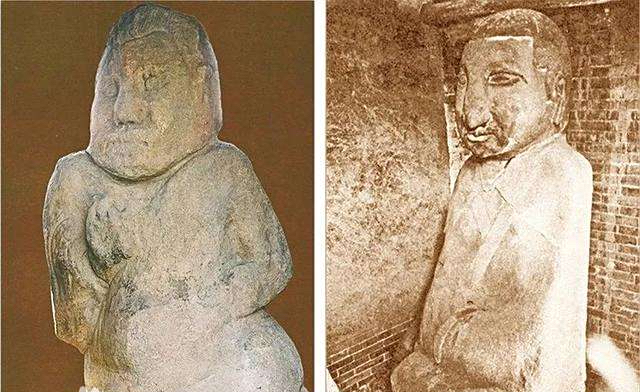

Stone statues of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl from the Western Han Dynasty

In the third year of the Yuanshou reign of the Han Dynasty (120 BC), Emperor Wu of Han excavated Kunming Pond within the Shanglin Garden to train naval forces for military operations in the southwest and to secure water resources for the canals and open channels. Stone statues of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl were carved on both sides of the pond, symbolizing the Milky Way and the stars Cowherd and Weaver Girl. The Cowherd is one of China's earliest surviving large-scale stone sculptures. Over two thousand years old, the stone sculpture is now located in Doumen Town, Chang'an District, Xi'an, approximately 3,000 meters away. The Cowherd stands 2.15 meters tall, with only his upper body visible above the ground. His right elbow is bent upward, as if holding a whip, his left hand pressed against his chest, grasping the reins, a simple and robust figure. The Weaver Girl is depicted kneeling, her hands clasped before her abdomen. She wears a long, right-fronted, cross-lapeled robe, her hair tied in a bun at the back of her neck.

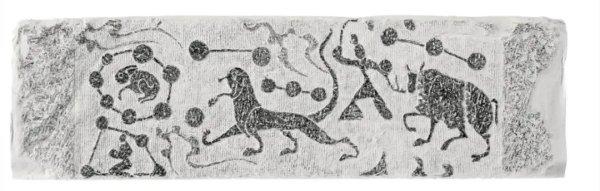

Stone rubbing of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl portrait (Eastern Han Dynasty)

The Cowherd and Weaver Girl stone relief from the Eastern Han Dynasty, housed in the Nanyang Museum of Han Dynasty Paintings, is an early example of this theme. Unearthed in the 1970s from the Baitan Han Tomb in Nanyang's Wolong District, this relief stone measures 186 cm long, 52 cm wide, and 27 cm thick. A white tiger is depicted in the center of the stone, its head held high and tail raised, as if running. Two connected stars are above its head, three connected stars are above its back, and a star is below its mouth, forming the symbolic Western "White Tiger" constellation.

Detail of a stone rubbing of the Cowherd and Weaver Girl portrait (Eastern Han Dynasty)

On the right side of the stone, a shepherd boy whipping a cow is depicted as the Cowherd. Above the cow, three stars are connected, representing the "Hegu Three Stars," commonly known as the "Cowherd Star." On the lower left side of the stone, a woman kneeling sideways, similar to the posture of Han Dynasty women weaving, is depicted as the Weaver Girl. Surrounding her are four stars connected, representing the Vega constellation, also known as "Nü Su." This stone relief, carved on the roof of a Han Dynasty tomb, symbolizes the sky and embodies the Han Dynasty's cosmological perspective.

Han Dynasty tomb murals from the Chang'an area during the same period are more narrative. The Weaver Girl, dressed in Han Chinese clothing, looks back at the Cowherd, leading the Cowherd, suggesting a budding romance. It's worth noting that the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl depicted in these early artifacts often retain a "divine" nature, not yet fully personified, unlike the more humanistic portrayals of the couple in later generations.

Tang and Song Dynasty Artifacts: Material Carriers of Folk Beliefs

During the Tang and Song dynasties, as the customs of the Qixi Festival became more sophisticated, the theme of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl appeared in large numbers in cultural relics, and the forms became more diverse.

Magpie Bridge motifs are common on Tang Dynasty bronze mirrors. For example, the Moon Palace Mirror in the Shanghai Museum features a magpie with its wings spread on its edge. While not directly depicting a human figure, the connection between the magpie and Qixi Festival is clear. The Suihua Jili quotes the Fengsu Tong (Comprehensive Customs) account of "the Weaver Girl uses magpies to form a bridge across the river on Qixi Festival," providing a folklore explanation for this motif.

Magpie Bridge patterns are common on Tang Dynasty bronze mirrors

Figurative depictions of scenes began to appear on Song Dynasty porcelain. Simple sketches of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, paired with auspicious phrases such as "eternal love," often appeared on Cizhou kiln pillows, reflecting the aesthetic tastes of the urban middle class. The "Dongjing Menghualu" records the grand market scene of "three to five days before Qixi Festival, with carriages and horses filling the streets, and silks and satins adorning the streets," which perfectly captures the social context for the production of these folk artefacts.

While the Mohele figurines of the Tang and Song dynasties didn't directly depict the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, they served as offerings during the Qixi Festival and were closely tied to the legend. The lines from Yuan Zhen's "Gu Ke Le" (Guke Le): "Seek profit, not fame; fame has its limits. Seeking profit is the pursuit of all, and Mohele has become a market," attest to the commercial production of these festive artifacts. The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl theme in Yuan Dynasty artifacts demonstrates a multicultural fusion.

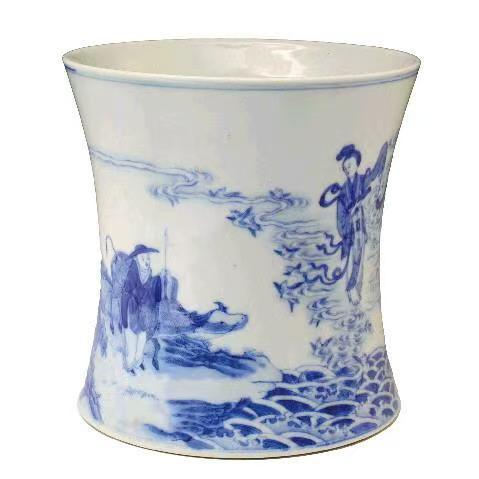

The decorative patterns on blue and white porcelain began to incorporate elements of opera. For example, the British Museum's Yuhuchun vase depicts the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl alongside characters from "The Romance of the Western Chamber," reflecting the influence of popular literature on arts and crafts. This crossover is directly related to the flourishing of Yuan Dynasty zaju (various opera). According to the "Lu Gui Bu," at least three zaju plays, including "Crossing the Tianhe River and Meeting the Cowherd," addressed this theme.

Gold and silver artifacts incorporate nomadic cultural characteristics: a gilded silver plate unearthed in Inner Mongolia features high-relief figures, and the Weaver Girl's clothing bears a distinct Mongolian style. This fusion of ethnicities reflects the diverse interpretations of the same legend in a multi-ethnic country.

Ming and Qing Dynasty crafts: a dual interpretation of the palace and the folk

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the production of cultural relics with the theme of Cowherd and Weaver Girl reached its peak, forming two style systems: court style and folk style.

Imperial artifacts were exceptionally exquisite. For example, the Palace Museum houses a Qing Dynasty bamboo incense tube, depicting a scene of a meeting on the Magpie Bridge, using openwork carving techniques. Auspicious clouds, magpies, and constellations are intricate yet seamless. Emperor Qianlong's inscribed verse, "Year after year, the Milky Way gazes at each other, waiting only for the auspicious day for the Magpie Bridge to connect," directly captures the theme. These pieces align with the "Qixi Festival Pattern" specifications in the "Qing Palace Household Department Workshop Records," demonstrating the institutionalization of imperial festival culture.

The Ming Dynasty blue and white "Autumn Eve" poetic ladies' bowl collected by the National Palace Museum in Taipei is a rich and colorful blue and white with different shades. The bowl is painted with Altair, Vega, curling cloud patterns or curling grass patterns, all of which have traces of diffuse flow, giving it a clear and elegant charm.

Ming Dynasty blue and white "Autumn Eve" poetic ladies bowl

Jingdezhen porcelain official kiln products are exquisitely crafted, such as the "Magpie Bridge Fairy Ferry" plate, which uses a pastel rolling process. The sky blue glaze is decorated with curling grass patterns, and the opening is painted with a scene of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl meeting. The Cowherd sits on the back of the cow, gazing at the Weaver Girl affectionately, while the Weaver Girl's clothes flutter as she also looks at the Cowherd. Auspicious clouds linger around, and magpies fly around. The four-character official kiln mark "Magpie Bridge Fairy Ferry" on the bottom confirms its status as an official festival vessel.

Qing Dynasty Jingdezhen official kiln Cowherd and Weaver Girl enamel plate

Qing Guangxu blue and white Qixi scroll

Folk crafts are imbued with a sense of life. The Cowherd and Weaver Girl story, carved on the lid of a Ming Dynasty red-carved dressing box, features simple forms yet heartfelt emotions. The Qing Dynasty Taohuawu New Year painting, "Seventh Night," features the Cowherd and Weaver Girl alongside a begging girl, skillfully blending myth and reality. These works echo the folk custom of "throwing away the needle at noon on the seventh day of the seventh month" in the "Imperial Capital Scenery," demonstrating the profound integration of legend and reality.

The themes of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl in cultural relics are often combined with specific folk practices, becoming the material carrier of festival activities.

The Palace Museum has a Qing Dynasty kesi silk scroll depicting the Qixi Festival, which features the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl meeting in the sky, while the lower part depicts the human world, where several women are either leaning on a railing, gazing into the distance, or praying for skills in the air.

Qiqiao props were directly used in Qixi Festival activities: Ming and Qing dynasty artifacts like the "Seven-Hole Needle" and "Qiqiao Plate" correspond perfectly to the description in the "Jingchu Sui Shi Ji" of "women weaving colorful threads through seven-hole needles." A Qing Dynasty Qiqiao box in the Tianjin Museum's collection contains seven different sizes of needles and threads, and its lid features a depiction of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, seamlessly integrating legend with Qiqiao practice.

Sacrificial utensils were used for ritual offerings: a Song Dynasty Jingdezhen kiln celadon bowl, with its outer surface carved with a magpie bridge motif, was specifically used for displaying melons and fruits on the Qixi Festival. This type of artifact corroborates the record in the "Wulin Jiushi" (Old Stories of the Wulin) that "Qixi Festival offerings often included fruit and roosters," demonstrating the material connection between legend and ritual. From Han Dynasty stone reliefs to Qing Dynasty official kiln porcelain, artifacts depicting the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl span two millennia, forming a comprehensive visual representation. These material remains not only record the evolution of the legend itself but also reflect the craftsmanship, aesthetic tastes, and folk customs of different historical periods.