In recent decades, exhibitions on ancient Egypt have been the star attraction of major museums around the world. Following the Shanghai Museum's exhibition on ancient Egyptian civilization, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is also poised to see a surge in visitors interested in ancient Egypt.

On October 12, the special exhibition "Egyptian Gods" opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Nearly 250 cultural relics and artworks revolve around images related to important gods in ancient Egypt, telling the story of how different classes in ancient Egypt interacted with gods.

Twelve years have passed since the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York last hosted a major exhibition of ancient Egyptian art that drew such large crowds. "Egyptian Gods" felt like a grand homecoming. Inside the exhibition hall, many prominent figures from ancient Egyptian civilization gathered to greet visitors. Some of these faces were familiar, while others might be new to the audience.

Over their 3,000-year history, the ancient Egyptians developed a vast belief system with over 1,500 deities. While the deities' appearances and personalities overlapped significantly, subtle differences in clothing, gestures, and the symbols they wore helped people identify and distinguish between them.

A statue of the lion-headed goddess Wadjet, displayed in the exhibition's cat-themed section.

The exhibition features treasures from the Metropolitan Museum's collection as well as items on loan from other leading institutions, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Louvre. The exhibition occupies the spacious second-floor gallery previously occupied by the special exhibition "Sargent and Paris." However, the focus of this exhibition is not on demonstrating political power but on conveying spiritual resonance.

As the title suggests, the exhibition presents the complete pantheon of ancient Egyptian deities, all executors of the cosmic enterprise known as "eternal life." The ancient Egyptians believed that the gods could enter human spaces through images and sculptures in tombs, temples, and niches, participating in rituals that bridged the mortal realm with the divine. For the pharaohs and high priests, daily rituals took place within the temples. Non-royal members, barred from the sanctuary, established connections with the gods through the worship of statues and offerings. The exhibition also showcases 25 key deities of ancient Egypt, including Horus, the hawk-headed patron god of the pharaohs; Sekhmet, the goddess of war; Ra, the creator god; and Osiris, god of the underworld, allowing visitors to engage in spiritual dialogue with them throughout the exhibition halls.

"The God Thoth Walking", 332-30 BC, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Diana Craig Patch, curator of Egyptian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and research assistant Brendan Hainline have created an open-plan exhibition that connects multiple independent spaces, each dedicated to a different ancient Egyptian deity. Visitors are thus invited to visit the abodes or temples of each deity, each of which reveals its own unique personality, along with the quirks, contradictions, and surprises it embodies.

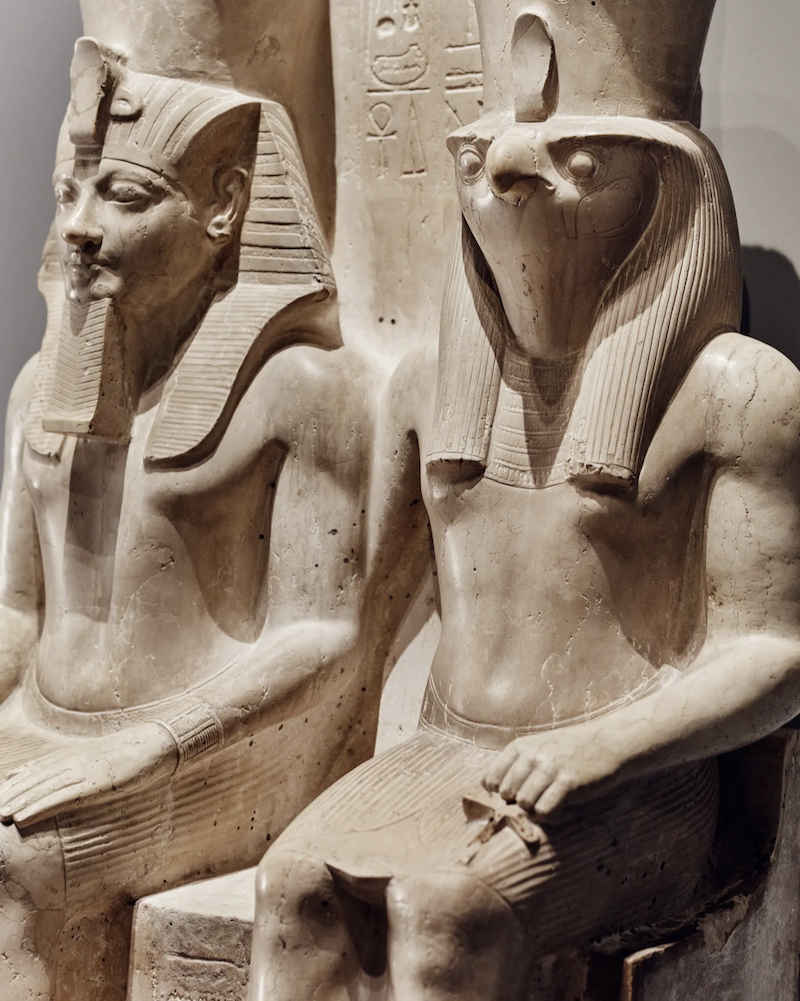

The statue of Amun-Ra guarding King Tutankhamun

The exhibition's opening offers a surprise. At the entrance, a majestic sculptural portrait, loaned from the Louvre, depicts two figures: the sun god Amun-Ra and the pharaoh Tutankhamun. From a contemporary perspective, Tutankhamun is undoubtedly the star attraction, a towering figure resembling a rock star and a guaranteed box office draw. Yet, here, he stands like a toddler, between the knees of a deity seemingly oblivious to his presence.

Even when the figures are similar in size, the divinity remains dominant. In a magnificent dark sandstone carving, the goddess Hathor sits on a throne beside King Menkaure. Though slightly larger in stature, she possesses a far more imposing presence. She wears an extravagant crown, framed by pointed horns and centered on a soft yellow disk, symbolizing the sun.

A triptych of statues of the goddess Hathor, between King Menkaure and figures from the Harenom region of ancient Egypt

This statue of Hathor, dating from the 2nd millennium BC and on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is one of the earliest known representations of the goddess and the centerpiece of a small exhibition dedicated to Hathor. Hathor long enjoyed a supreme position, with temples dedicated to her, dedicated female attendants, and many other goddesses, such as Isis, emulating her shifting features. In human form, Hathor championed motherhood; in lioness or serpent form, she became a protector of her followers; and in bull form, she became the central force of cosmic creation, holding the sun above her head and bringing light to the new world.

Several artifacts on display offer glimpses of Hathor's physical manifestations: miniature human figures carved on stone seals; half-human, half-animal faces on the handles of musical instruments; and a life-size bull's head carved from milky white alabaster. Several of her incarnations are collectively depicted in a single, colossal sandstone statue, all faces worn by the devout caress of devotees. This section sets the stage for subsequent dedicated sections dedicated to various deities.

Relief of the Goddess Maat

The goddess Maat is often depicted as a serene, youthful beauty, with a fixed image and iconic symbol: a feather standing upright in her hair. Maat, whose name means "right," is the guardian and arbiter of moral values such as truth and social justice. Her duty is to judge people based on their adherence to these ideals. During judgment in the underworld, she places the feather on one end of a scale and the heart on the other. People can only pray that the two weigh equal weights.

Like the goddess Maat, the sky god Horus consistently appears in a single form: with the body of a falcon or a human body with the head of a falcon. A captivating limestone sculpture in a display case depicts him in this bird-man form, seated on a throne beside the pharaoh Horemhab. The pharaoh's expression, a slight smile, suggests a mixture of anxiety and amusement. Overall, however, diversity was the dominant theme among the ancient Egyptian gods, and interspecies integration was the guiding principle.

Double limestone statue: Horemheb and Horus

The moon god Thoth appears in some cult images as a human with a heron's head, while in others he appears as a baboon. Seth, the two-faced deity representing both good and evil and known as the "god of chaos," is depicted as a nightmarish hybrid, a monstrous creature with horns, a pig's snout, and a forked tail. Goddesses with feline features are also common, with Bastet and Sakhmet being two of the most iconic. These deities were beloved by the public millennia ago and remain highly sought after in museums today.

The god Thoth is transformed into an ibis, with his followers beside him.

Because so much of ancient Egyptian art survives in funerary form, we tend to assume the culture that created it was inherently morbid and death-obsessed. However, the theme of the Met's exhibition is their unquenchable vitality, even in the face of death.

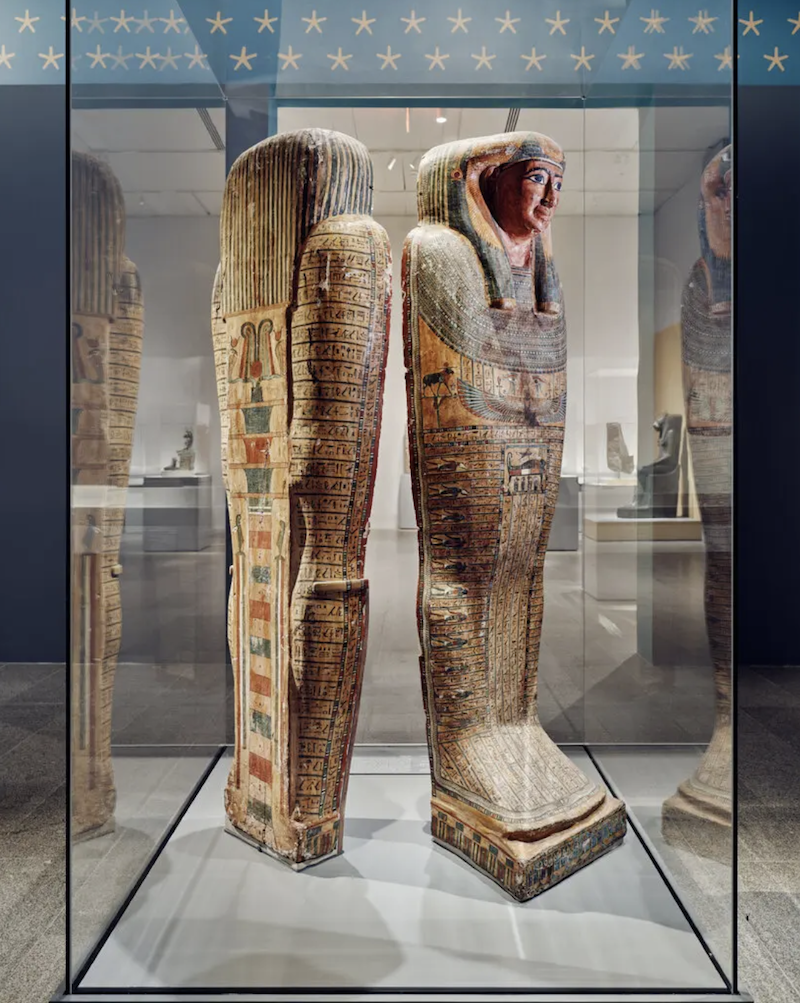

A vivid portrait depicts Nut, the sky goddess. Painted on the lid of the coffin of a woman named Wedjarenes, the half-life-size image depicts Nut as a youthful, athletic figure, nearly naked, her limbs stretched out. An orange sphere, the size of a basketball, hovers above her head, while another, smaller sphere rests between her legs. Why? Because she devours the sun each night and regenerates it at dawn, a cycle of eternal rebirth that mirrors the journey of the coffin's occupant.

Vejarenes Coffin

Eternity, as an active and vibrant state, is the central theme of these works of art. This state should belong to everyone. While it's true that the monumental works in museum collections were accessible only to the nobility and the priesthood, a vibrant folk religion also existed, with images created and enshrined on home altars or paraded through the streets on boat-shaped floats. In the display case, visitors can see a float-like device carrying a small sculpture group.

At the exhibition, the display cabinets were arranged in the shape of a boat, and small sculptures were placed in the display cabinets. These were sculptures made by folk religions at that time and dedicated to family altars.

When crossing the fluid boundary between this life and the afterlife, the process is the same for everyone. Ancient Egyptians were guided into the next realm by a jackal-headed deity, as slender as a Saluki. His name was Anubis. He would lead them to the most alluring of the gods: Osiris, Egypt's eternal ruler and master of the afterlife.

Limestone statue of Anubis, ruler of the underworld, depicted in a reclining canine position

Osiris appears repeatedly at the end of the exhibition hall. In most of the displays, he is dressed in his signature garb: wrapped head to toe in white mummy-like bandages. The story behind this imagery is that Osiris's jealous brother, Set, killed and dismembered him; his sister and wife, the goddess Isis, rewrapped his body and brought him back to life.

A group of gold-cast sculptures of three gods appear at the end of the exhibition. Horus, Osiris, and the son of Isis, all with eagle heads and human bodies, stand on the right side of the great god in a dancer-like posture. On the left is Isis, wearing a sun crown, showing a well-trained and elegant posture. They constitute the highest-level farewell lineup, completing a farewell ceremony for the audience.

Welcoming scene: Horus with an eagle head and a human body, Osiris covered in a shroud, and Isis wearing bull horns and a sun disk.

Osiris, Horus and Isis, 22nd Dynasty Egypt, Louvre Museum

But Osiris himself did not stand. He sat cross-legged at the top of the column, knees drawn up to his chin. He was short, with narrow shoulders and large ears. His face was a mixture of the mature of a teenager and the childishness of an old man. Despite his crown, he looked like a child. He stared straight ahead. What was in his eyes? Curiosity? Confusion? Awe? All of these were natural responses to such a grand display.

Osiris worship stele

The exhibition will run until January 19, 2026.