The two special exhibitions "From the Humble Administrator's Garden to the Records of the Great Objects" and "From the Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden" currently being held at the Suzhou Museum have become the focus of attention in the cultural and art circles.

In this exhibition, which is hailed as "the largest garden-themed special exhibition in Suzhou", The Paper discovered that works by five generations of literati, calligraphers and painters from the Wen family of the Ming Dynasty, represented by the Ming Dynasty calligrapher and painter Wen Zhengming and his great-grandson Wen Zhenheng, were gathered in the exhibition hall. It not only witnessed the cultural heritage of a family, but also presented the achievements of Suzhou's calligraphy and painting art in the Ming Dynasty and the literary spirit of Jiangnan over the past five hundred years.

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559)

A brief genealogical table of the Wen family in the Ming Dynasty (Suzhou Museum)

The inclusion of gardens in paintings and the foundation of Wen Zhengming's art

When the audience stopped at the first chapter of the garden special exhibition in the West Hall of Suzhou Museum, the small-character calligraphy "Returning to the Countryside" written by Wen Zhengming at the age of 82 presented not only a masterpiece of calligraphy, but also the inner monologue and spiritual enlightenment of an art master.

Wen Zhengming's "Returning Home" in Regular Script, from the collection of the Palace Museum

In the autumn of the 30th year of the Jiajing reign (1551), aboard a small boat in Hengtang, this octogenarian copied Tao Yuanming's famous poem "Retreat" in unbounded small regular script. His brushwork is elegant and graceful, the structure is square and tight, and the entire work is free and natural, with not a single stroke wasted. Wang Shizhen recorded in "Yanzhou Shanren Sibu Gao" that "Wen Shi wrote a piece of small regular script every morning and evening as a daily routine." This daily practice, continued even at the age of 80, established the pinnacle of small regular script art in the Ming Dynasty.

The leisurely and peaceful mood of enjoying one's remaining years revealed in "Returning to the Countryside" forms a spiritual resonance across art categories with the Humble Administrator's Garden, which Wen Zhengming participated in designing in his later years.

Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tujuan" (partial) from the National Museum

The "Zhen Shang Zhai Scroll," also on display in the exhibition, directly reveals how Wen Zhengming translated his gardening philosophy into visual language. The scroll unfolds slowly from right to left, first catching the eye is a group of tall, graceful Taihu rocks. These exquisitely carved rocks, resembling overlapping peaks, are both bizarre and elegant in form. Green trees and red flowers interspersed among the rocks add a vibrant atmosphere. Further left, two thatched huts, shaded by a clump of bamboo, are nestled among pine, cypress, and sycamore trees. On the right, wooden shelves are filled with scrolls, while on the left, two scholars sit facing each other at a table. The study in the painting echoes the courtyard, with a well-arranged arrangement of flowers and trees. The layout of the Taihu rocks, pine, cypress, and bamboo embody his ideal of an "urban forest."

Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu Juan" is from the collection of the National Museum

Family tradition and new trends: the second generation of the Wen family inherits the changes

"Looking at the Snow Mountain Tower, I recall the past, where thousands of jade flowers dance in a riot of color. Years have passed, leaving me in empty dreams; today, we part ways. The years pass like fleeting messages, and I feel guilty for wasting my career. The winter plum blossoms may not have completely withered, for the autumn moon and spring flowers will still bloom." Wen Peng, Wen Zhengming's eldest son, created a fan-shaped poem in cursive script, showcasing unrestrained brushwork and vibrant strokes, each line exuding a carefree and heroic spirit. Unlike his father's strict and rigid style, Wen Peng's cursive calligraphy is free and unrestrained, effortlessly free. Wang Wenzhi of the Qing Dynasty commented that his "mastery is not as good as his father's, but his free and unrestrained spirit far surpasses his."

Wen Peng's "Cursive Poetry" fan leaf, Wuxi Museum collection

Wen Jia, "Red Lotus in the Autumn Pond," from the collection of Tianjin Museum

On one side of the display case, Wen Zhengming's second son, Wen Jia, painted "Red Lotuses in an Autumn Pond," inspired by the Yuan Dynasty painter Ni Zan. In the foreground, tree branches sway in the autumn breeze, while a few lotus leaves and red lotuses emerge from the water. The composition is sparse and the brushwork is simple. In the distance, winding mountains appear, creating a profound artistic conception and elegant style. The artist inscribed the painting in running script: "A night of west wind, an autumn pond, scattering many red lotus flowers." The signature is "Wen Jia, painted in Ruoshu Hall, Humble Administrator's Garden," in a flowing and elegant style. The painting depicts the clear and elegant literati garden scene of the Ming Dynasty.

While inheriting his family's tradition, Wen Jia developed a more simple painting style. The floral and bird elements in his paintings later became an important source of inspiration for the plant arrangement of Suzhou gardens.

Wen Boren, "Shihu Thatched Cottage" (partial), Suzhou Museum

Wen Boren, "Shihu Thatched Cottage" (partial), Suzhou Museum

The most captivating family conversation in the exhibition occurs in front of Wen Zhengming's nephew, Wen Boren's "Shihu Thatched Cottage Scroll." This 142.4-centimeter-long, stained-color handscroll depicts Shihu Thatched Cottage at the foot of Mount Lengjia in Suzhou. The painting features winding paths around the lake, shaded by pine and bamboo trees. The owner sits at a desk in the thatched cottage, unfolding a scroll, attended by a young boy. A lone monk can be seen walking in front of a temple. A boat can be seen moored on the lakeside, awaiting a ferry crossing. The painting's sparse brushwork and elegant colors create a quintessential image of seclusion and reading.

Wen Boren's landscapes fall into two general styles: simple, imitating the fine brushwork of Wen Zhengming, typically featuring open compositions and delicate brushwork; and elaborate, emulating the complex, lush landscapes of Wang Meng, often featuring dense layouts and layered peaks. This scroll emulates Wen Zhengming's fine brushwork, with meticulously outlined mountain gates, sloping stairs, and main halls. The white space left over from the lake creates a highly lyrical effect.

Wen Boren, "Shihu Thatched Cottage" (partial), Suzhou Museum

Shihu Thatched Cottage is where Wen Zhengming's favorite disciple Wang Chong studied. Wen Zhengming's "Tombstone Inscription of Wang Luji" says of him: "He studied under Mr. Cai Yu when he was young, lived in Dongting for three years, and then studied on Shihu for twenty years. He would not go into the city unless it was the annual visit. When he encountered beautiful mountains and rivers, he would be so happy that he would forget to leave. Sometimes he would rest among the long woods and lush grass, compose poems with a drunken look, sing while leaning on the mat, and feel as if he had thoughts of thousands of years ago." The creation of this scroll came about because Wang Chong once copied Zhu Zhishan's "Preface to Sending Yang Hou to the Emperor" here and gave it to his disciple Yuan Bin. Yuan Bin took it to Beijing and asked Wen Boren to add illustrations to it.

Wang Xideng of the Ming Dynasty accurately summarized it in "Wujun Danqingzhi": "(Wen Zhengming)'s son Jia and his nephew Boren both inherited his art. Jia's paintings are full of lush bamboo and trees, while Boren's paintings are lush and dense mountains and hills." The exhibition juxtaposes Wen Boren's "lush and delicate" painting style with Wen Jia's "lush bamboo and trees" works, allowing the audience to intuitively experience the different artistic personalities within the same family.

Wen Yuanfa's "Cursive Script Poetry Fan Page" is from the collection of the Palace Museum.

Wen Yuanfa, grandson of Wen Zhengming and son of Wen Peng, was a key figure in continuing the Wen family's artistic style. Having lost his mother at a young age, Wen Yuanfa lived with his grandfather, receiving his guidance. He excelled in poetry, calligraphy, and painting, influencing his sons Wen Zhenmeng and Wen Zhenheng. All three, father and son, were renowned for their poetry, calligraphy, and painting. The exhibition features a fan scroll of running script poetry, a copy of "Zhongshan Poems" by the late Yuan and early Ming poet Yang Weizhen. Its style is influenced by Wen Zhengming's late studies of the Huangting Sutra.

The Album of Tang Dynasty Poetry and Wen Zhenheng's Masterpiece

At the special exhibition, "Album of Tang Poetry" by Wen Zhengming's great-grandson Wen Zhenheng attracted much attention. This album incorporates Tang poetry into paintings and transforms the poetic scene into visual imagery. It not only demonstrates the exquisiteness of the technique, but also reflects the spiritual dwelling of the literati in the turbulent times of the late Ming Dynasty.

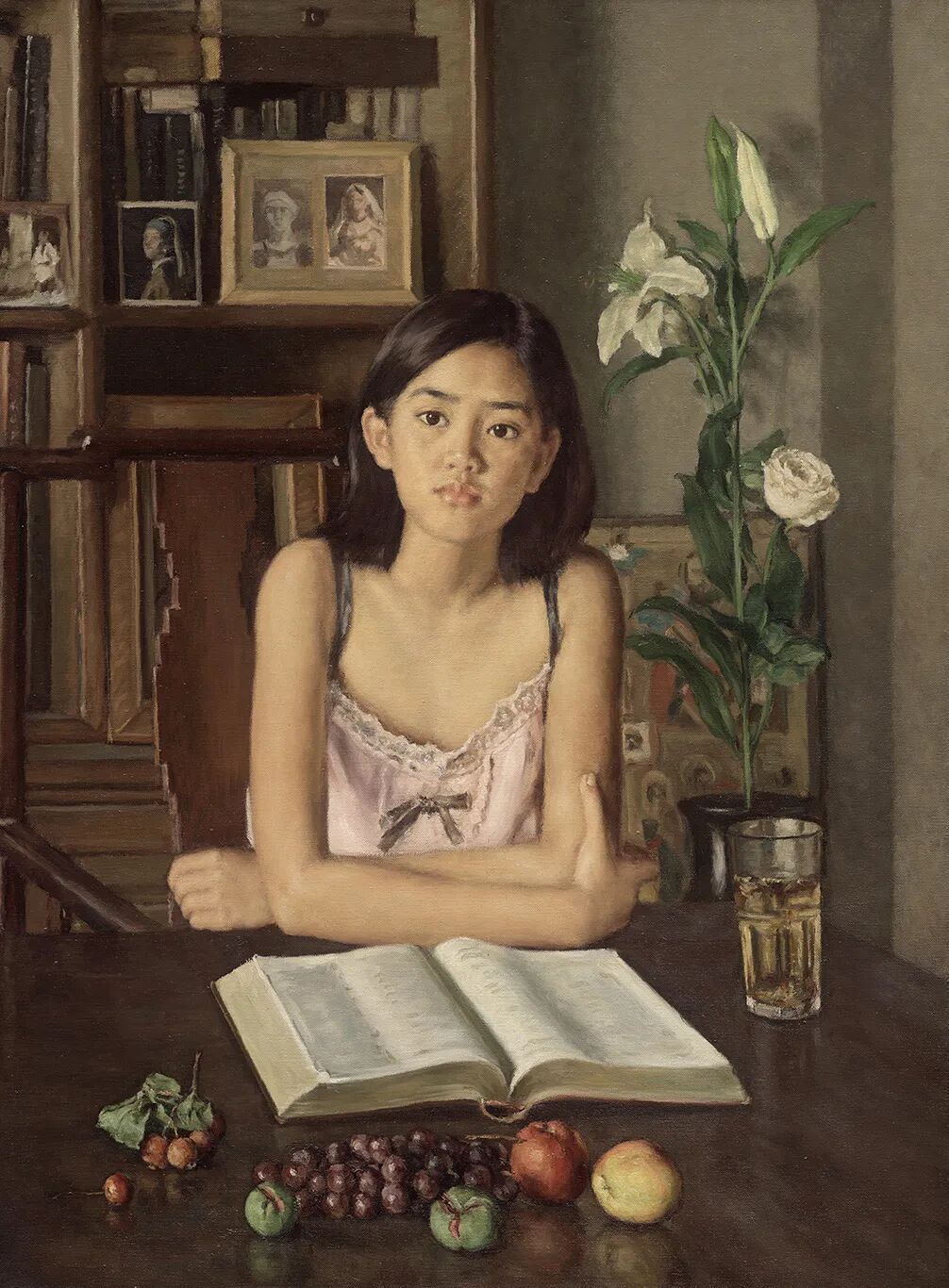

Wen Zhenheng's Album of Tang Dynasty Poetry, leaf 10, "Poetic Concepts of Bai Juyi" (from the collection of the Palace Museum)

Each leaf in the "Album of Tang Poetry" corresponds to a Tang Dynasty quatrain, encompassing poems by twelve poets, including Bai Juyi, Li Shen, Lu Tong, and Shi Jianwu. In his inscription, Wen Zhenheng bluntly stated, "The image need not perfectly match the verse, but the lofty sentiment transcends the brush and ink." This creative concept transcends the constraints of form and directly aims to reconstruct artistic conception. For example, leaf 7, "Lu Tong's Poetry" (Hungry, Eating Pine Flowers, Thirsty, Drinking Spring Water): The painting depicts a mountainscape painted with azurite and malachite green. A hermit in white robes lies among the soft grass on a sunny slope, accompanied by deer and elk. The poet's wild interest in "living in harmony with nature" is captured through the contrast between the delicate lines of the figures and the rugged texture of the rocks, creating a transcendent visual rhythm. Leaf 10, "Bai Juyi's Poetry" (Secluded Place, Deep Gate, Few Greeters): An old man walks alone, carrying a rattan cane, amidst a path strewn with fallen leaves in an autumn garden. The painter uses ochre to dot the withered leaves, while ink outlines the twisted branches. The sparseness reveals the Zen spirit of "sitting idly in clothes, cultivating a quiet mood." This type of treatment highlights Wen Zhenheng's refinement of the key points of poetry - abandoning narrative in favor of state of mind, making the picture an extension of the spirit of the poem rather than an illustration.

"Poetic Concepts of Wu Yuanheng" from Wen Zhenheng's Album of Tang Poetry, fourth leaf, from the collection of the Palace Museum

As the great-grandson of Wen Zhengming, Wen Zhenheng's techniques are deeply rooted in the traditions of the Wu School of Painting, while also incorporating his own unique innovations. In the fourth section, "Poetic Inspiration of Wu Yuanheng," the figure of a bamboo-planting sage is sketched with only a few strokes, emphasizing his detached demeanor, "ignoring the affairs of the city walls all year long." This style, characterized by "elaborate yet unforced, free yet undisciplined," reflects the transition from realism to freehand brushwork in late Ming art, and echoes the aesthetic principle of "preserving the past without time" as expressed in the book "Changwuzhi."

Wen Zhenheng's "Changwuzhi" (Records of Superfluous Things), a late Ming edition, collected by Ningbo Tianyi Pavilion Museum

"Album of Tang Dynasty Poetry and Paintings," passed down through the collections of Tan Guancheng and the Qing Imperial Household, bears seals such as "Treasure for the Jiaqing Emperor's View" and "Treasure for the Xuantong Emperor's View." Its binding and materials are also precious: the base is made of "Chengxintang paper," which is as flexible as silk, and the ink color remains bright and smooth after centuries. Wen Zhenheng explains the origin of his creation in the inscription: "Jiaqing had Chengxintang paper, which I cut into twelve frames... I paint by my window when I feel inspired," demonstrating the seriousness with which he entrusted his thoughts and feelings with this rare material. Viewed today, this album is not only a pinnacle of the late Ming dynasty's fusion of poetry and painting, but also offers modern readers a reference to the classical aesthetic of life. As advocated by the "Changwuzhi," true elegance lies not in the accumulation of objects, but in a life attitude that "wanders with the mind in objects."

The fifth generation of the Wen family, Wen Chu, the great-great-granddaughter of Wen Zhengming and daughter of Wen Congjian, inherited the family tradition from a young age and was deeply influenced by Wen Zhengming's "pure, elegant, and refined" Wumen style of painting. The delicate boneless wash painting and the integration of poetry, calligraphy, and painting in her "Flower Album" all reflect the influence of the Wen family tradition. As a female artist, her natural history illustrations in "Descriptions of Metal, Stone, Insects, and Plants" expanded the subject matter of literati painting, making her a leading figure among boudoir painters of the Ming Dynasty.

Wen Chu's "Flower Album" is collected by Qingdao Museum

For example, Wen Chu's "Flower Album," exhibited at the Qingdao Museum, boasts pure composition and rich connotations, embodying his aesthetic philosophy of "expressing the heart through plants and trees." Wen Chu transformed Wen Zhengming's "pure and elegant" Wumen color tradition into a more decorative, feminine language. For example, in the first leaf, the veins of the daylily leaves are outlined with fine double-hook lines, while the petals are smudged with a "boneless overlay" technique, using rouge and gamboge gradients to recreate the realistic spirit of the Compendium of Materia Medica. The butterfly's antennae are as slender as hair, and the veins of its wings are clearly discernible, embodying the qualities of "vivid beauty and vividness, and a detailed depiction of the emotions of nature."

Wen Zhenheng's landscape scroll on display

In the Suzhou Museum, you can actually walk out of the exhibition hall and look for the wisteria planted by Wen Zhengming. From gardens to pavilions, from Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu Juan" to the "Chang Wu Zhi" defined by Wen Zhenheng, the Suzhou Museum's double exhibitions, in the interweaving of light and shadow between lake rocks and pavilions, make people feel the Wen family's spiritual pursuit of using "Chang Wu" to resist vulgarity, as well as the Jiangnan literary spirit that has been passed down for five hundred years.