Francis Bacon said in "On Horticulture": "The starting point of civilization began with the construction of castles. But advanced civilization is inevitably accompanied by beautiful gardens." Almost all famous artists in the East and the West are fond of the beauty of gardens and flowers, whether it is the Impressionist master Monet, Wen Zhengming of the Ming Dynasty in China, or Richard Wilson, the "Father of British Landscape Painting", or Qiu Ying and Wu Changshuo.

When Monet's garden water lilies meet the garden lake stones painted by Ming Dynasty literati painters Wen Zhengming and Wen Zhenheng, what kind of cross-time and space garden dialogue will it be? In particular, such a dialogue takes place in Suzhou, a garden city famous for its Humble Administrator's Garden and Lion Grove. On July 15, the annual special exhibition of Suzhou Museum, which is also the largest garden special exhibition in Suzhou, "From Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden", was officially opened to the public in the West Hall of Suzhou Museum. "The Paper|Ancient Art" visited the exhibition site.

The exhibition features a grand plan and displays, and extremely rich cultural relics. With the theme of Suzhou's most prestigious garden culture, the exhibition is jointly organized with 14 public institutions at home and abroad, including the Palace Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago. A total of more than 160 exhibits are on display, including 63 pieces/sets of national first-class cultural relics and cultural relics on loan from abroad. It presents literati collections ranging from Song and Yuan Dynasty calligraphy and painting to the Four Masters of Wumen, from precious bronze and stone artifacts, stationery to the five famous kilns, from the garden scenes described by the three masters of Ukiyo-e to the moments of light and shadow in Monet's water lilies...including Monet's masterpieces "Water Lilies" and "Water Lily Pond", Ming Dynasty Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu", and Wen Zhengming's great-grandson Wen Zhenheng's "Tang People's Poetry Picture" and other famous works.

"This special exhibition is the third phase of the 'World Cultural Heritage Series' exhibition of Suzhou Museum after Dazu Rock Carvings and Dunhuang Art. The exhibition takes the gardens that Suzhou people are most familiar with as the theme, starting from 'local culture', tracing the development of Eastern and Western gardens, and focusing on Suzhou's classical garden art and literati's elegance." Xie Xiaoting, director of Suzhou Museum, told The Paper that the exhibition was originally planned to start with the question of "why there are gardens", from the spirit of literati in the Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, to the construction of the Humble Administrator's Garden, to the case of cultural exchange and mutual learning between China and the West, and finally to Monet's Garden. "The difference between our exhibition and the Forbidden City's garden exhibition last year is that the Forbidden City is parallel, but ours is linear: from ancient Chinese gardens to the later exchange of Chinese and Western garden art, to the later Monet Garden, because the Humble Administrator's Garden is earlier than Western gardens after all."

Exhibition content planner Lu Wentao said that although the Humble Administrator's Garden and Monet's Garden are located in the east and west, they are both examples of poetic living. The exhibition not only juxtaposes the East and the West, but is also a dialogue across time and space - inviting the audience to step into the space where lake rocks and water lilies are intertwined, and to gain insight into the beauty of the garden in the exhibition combination of objects and paintings.

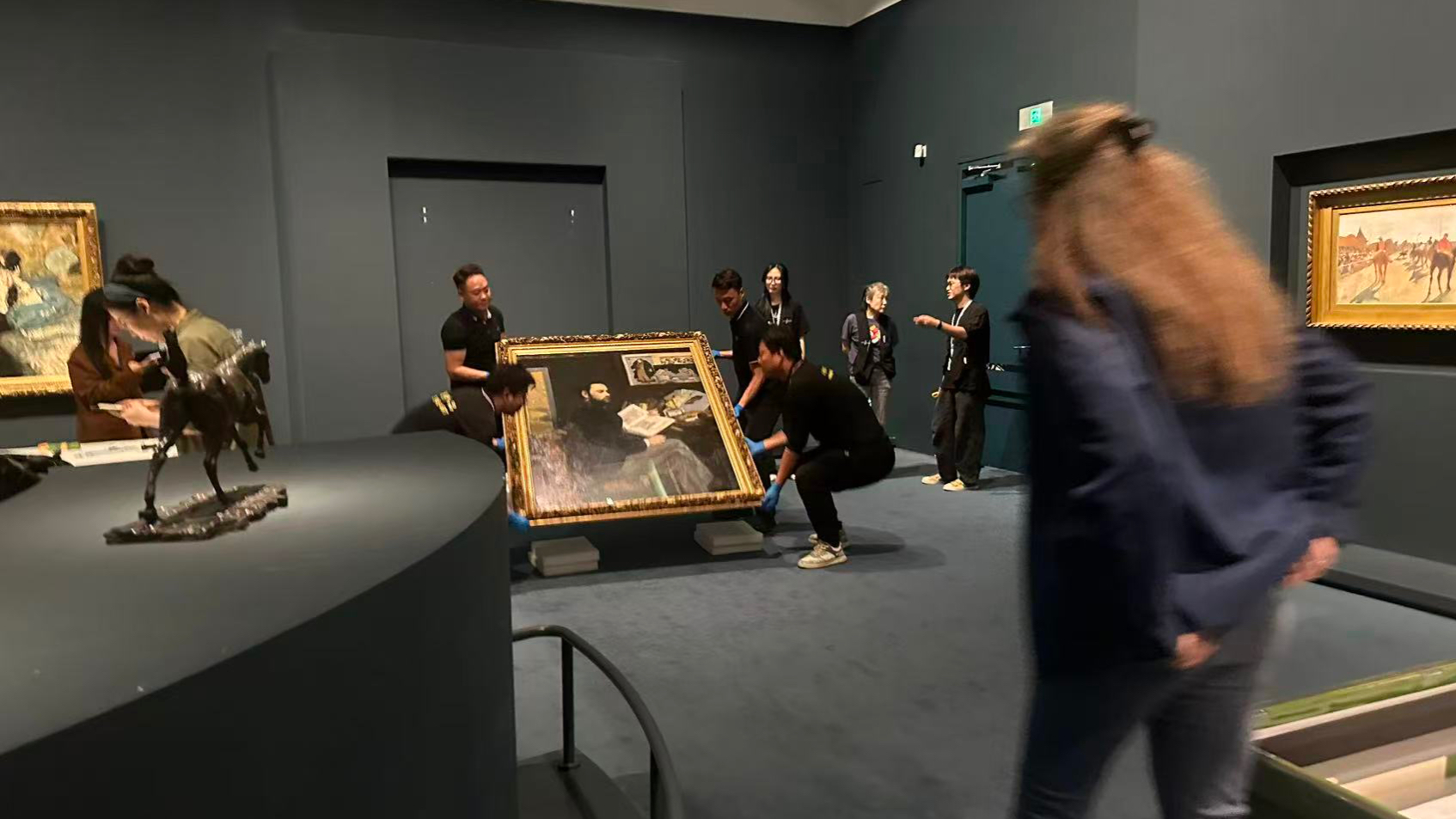

Exhibition site

The reporter from The Paper saw at the exhibition site that the exhibition is divided into five parts: "Free and Easy in the Forest and Springs: Spiritual Guidance of Hermit Sages", which explores the hermit ideal in the writings of literati of all dynasties and reveals the origin of garden culture; "Governance by Humble Administrator's Garden: Garden Practice in Suzhou in the Ming Dynasty", uses the Humble Administrator's Garden and the gardening art of Wen Zhengming's family in Suzhou as samples to show the profound influence of the Wumen elite on garden art; "Hills and Valleys Are Created by Nature: Landscape Art of Jiangnan Gardens", focuses on presenting the mountains, rivers, trees, stones, pavilions, towers, flowers, birds, insects and fish in calligraphy and painting works, showing the garden landscaping skills and classic landscapes captured by pen and ink; "Daily Fun: The Ultimate Elegance of Life in the Garden", focuses on life in the garden, and shows the life interest of literati through "long-term objects" such as stationery collections; "Sharing Beauty in Foreign Lands: World Gardens that Observe Each Other", looks to the international community and explores aesthetic resonance under a global perspective through paintings such as "Anglo-Chinese" gardens and Monet's gardens.

Exhibition site

Let's start from the seal script "逍遥游": Free and unrestrained in the forest and springs

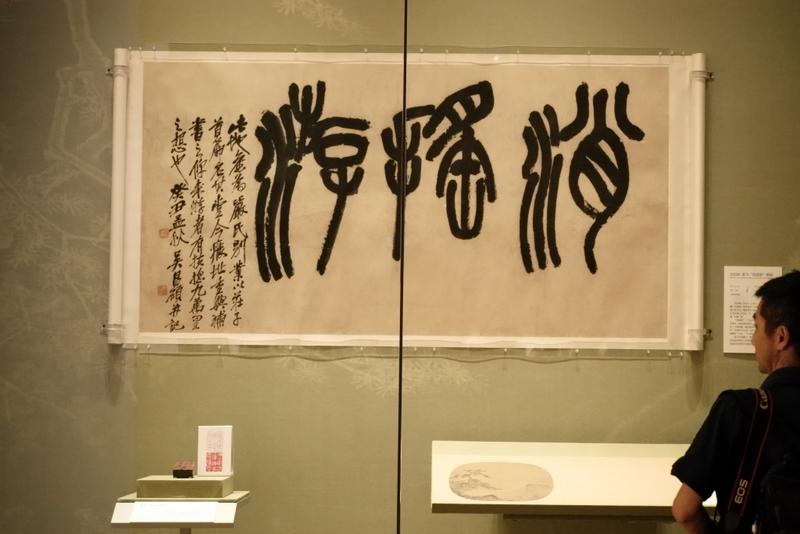

Entering the exhibition hall, a half-meter-long, majestic and visually impactful horizontal scroll of Wu Changshuo's seal script "Xiao Yao You" opens the exhibition. These three characters are written in small seal script, incorporating the brushwork of stone drum inscriptions, with vigorous and vigorous lines, full of the flavor of bronze and stone. "Laozi and Zhuangzi's teachings endow Xiao Yao You with romantic imagination, which actually expresses the longing and pursuit of spiritual freedom beyond reality, and the garden construction of later generations has been deeply influenced by it." Lv Wentao said during the on-site tour.

Wu Changshuo's seal script "Xiaoyaoyou" at the exhibition

"Moon Viewing under the Pine Tree" (partial)

The "Moon Viewing Under the Pine Tree" exhibited in the display cabinet below the seal script "Xiaoyaoyou" is a typical Southern Song Dynasty sketch. On the left is a tall pine tree standing upright, with old branches twisting and winding upwards. On a rock under the pine tree, a noble scholar sits slightly backward, looking up at the sky, with a servant standing behind him. In the distance, a full moon appears and disappears in the clouds. The distant mountains are outlined with lines, and the trees and grass are slightly colored, appearing hazy. The rocks in the foreground are outlined with axe-chopped texture, with a hard texture and a strong three-dimensional sense. The whole picture has a simple composition and a well-organized layout, which is quite similar to Ma Yuan's style.

Literati and scholars of all ages have always been deeply in love with nature, and they long to linger in the mountains and rivers, chanting and enjoying the moon, just like the characters in the paintings. Chinese classical gardens provide an ideal space for them to borrow from nature and enslave the moon, so that they can also enjoy the beauty of the mountains, forests and moonlight between the city buildings.

In the history of Chinese gardens, there are three cultural events that have been passed down from generation to generation, which have triggered the admiration and deconstruction of garden construction in later generations, namely "Traveling in the Bamboo Forest", "Purging the Pure Land at the Lanting Pavilion" and "Tao Yuanming's Return". If we analyze them, we will find that from the "pure and natural" bamboo forest to the "temporary happiness" of the Lanting Pavilion and then to the "cultivating the fields in the Nanshan Mountains", what people pursued was nothing more than a normalized landscape tour. For example, the anonymous "Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove" from the Ming Dynasty on display reproduces the heroic and unrestrained style of the "Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove", and also embodies the admiration of later generations for the reclusive spirit of the famous scholars of Wei and Jin metaphysics; the Wuxi Museum's copy of Zhao Mengfu's "Lanting Preface" inherits the tradition of the calligrapher, while carrying its own elegant, vigorous, clear and unrestrained style of calligraphy; Wen Zhengming's regular script "Returning to the Countryside" is elegant in brushwork, and the ambition to retire is revealed between the lines; Zhou Chen's "Peach Blossom Spring" uses a brush to transform the story of "Peach Blossom Spring" into a spectacular picture, recreating the Peach Blossom Spring on paper.

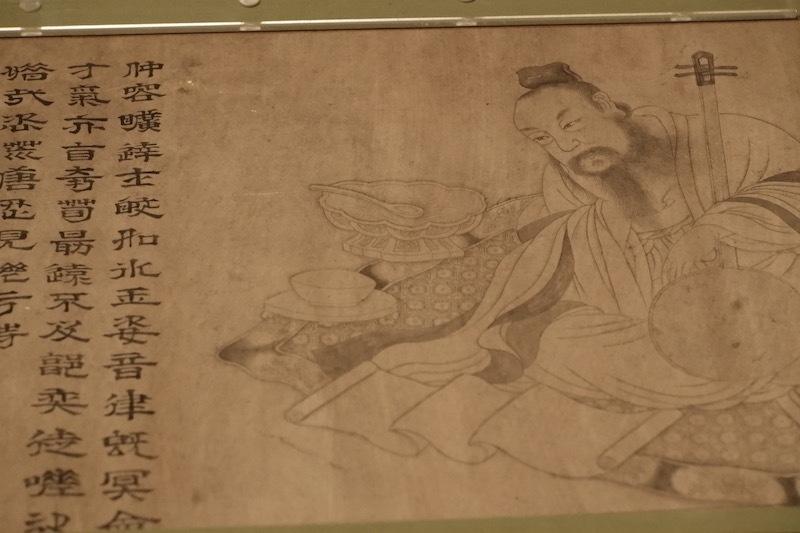

Anonymous "Seven Sages in the Bamboo Grove" (partial) from the Ming Dynasty

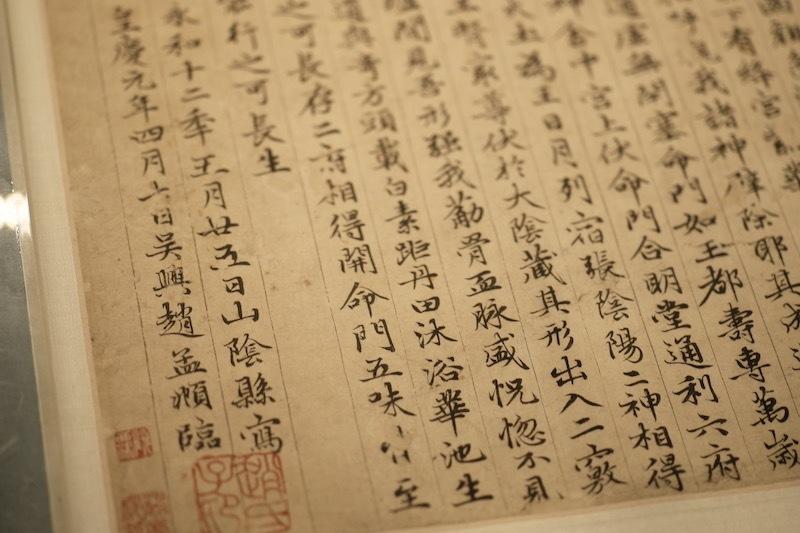

Xibo copy of Zhao Mengfu's copy of Lanting Preface (partial)

The beauty of gardens can be seen in objects and paintings

Suzhou has been a place of beautiful landscapes and rich cultural heritage since ancient times, and garden-building activities have continued for thousands of years. In the 16th century, scholars from Wu, led by Wang Ao, compiled the book "Gusu Zhi", which specifically records the geography and cultural prosperity of Suzhou in the middle of the Ming Dynasty. Two separate volumes, "Houses" and "Gardens", describe Suzhou's garden-building activities in detail.

As the political and cultural center moved south, the "painter's elegance" returned to Suzhou, and a large number of outstanding painters gathered here. They traveled around and built gardens, wrote articles and painted, combining the style of the court painters with the temperament of literati. With their elegant and refined artistic style, they gradually became the mainstream of the painting world at that time, known as the "Wumen School of Painting". Its representatives Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, Tang Yin, and Qiu Ying were especially respected by later generations and collectively known as the "Four Masters of the Ming Dynasty". For example, Tang Yin's "Poems of Summer Vacation at Wumen" scroll, Shen Zhou's "Paying Gratitude to Yinghua" scroll, and other masterpieces on display show their love and ideals for garden life.

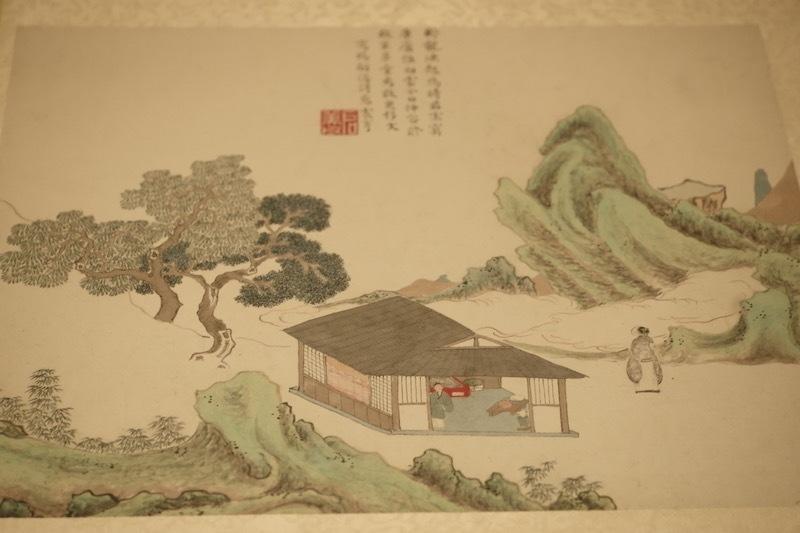

Wen Zhenheng's "Poetic Paintings of Tang Dynasty"

The "Poetic Scenes of Tang Dynasty" was painted by Wen Zhenheng, the great-grandson of Wen Zhengming in the Ming Dynasty. This album uses Tang Dynasty poetry to depict the leisure and elegance of literati. There are twelve pages in total, and each page contains a seven-character quatrain poem by a Tang Dynasty poet. According to the inscription on the back of the album, the paper used is quite exquisite, "Chengxintang Paper". The mountains and rocks in the picture are outlined and rubbed with ink pens, and dyed with blue and green. The colors are rich and elegant; the lines of the characters' clothes are delicate, and the furnishings and houses are extremely well-detailed. The whole picture is full of decorative interest from the painting method to the color. Although the poetic sentiment is reproduced in light green, the painting is already a garden in the painting that can be visited and lived in, with a profound artistic conception.

In the middle and late Ming Dynasty, gardens of all sizes sprang up all over Jiangnan, becoming an important space for scholars to express their emotions and cultivate their spirits. At the same time, a series of cultural practices around gardens, such as garden painting creation and garden theory writing, also made garden construction no longer just a spatial construction behavior, but evolved into a comprehensive cultural activity.

There is an inherent commonality between gardens and paintings. Both are aimed at the interest of mountains and rivers, share the same aesthetic foundation, and continue to evolve through mutual influence and interaction. The rise of the trend of traveling in the Ming Dynasty made this connection even closer. Wumen painters often created "travel records" based on their own travels, such as Wen Zhenheng's "Baiyue Tour", which is a visual record of his travels to Qiyun Mountain.

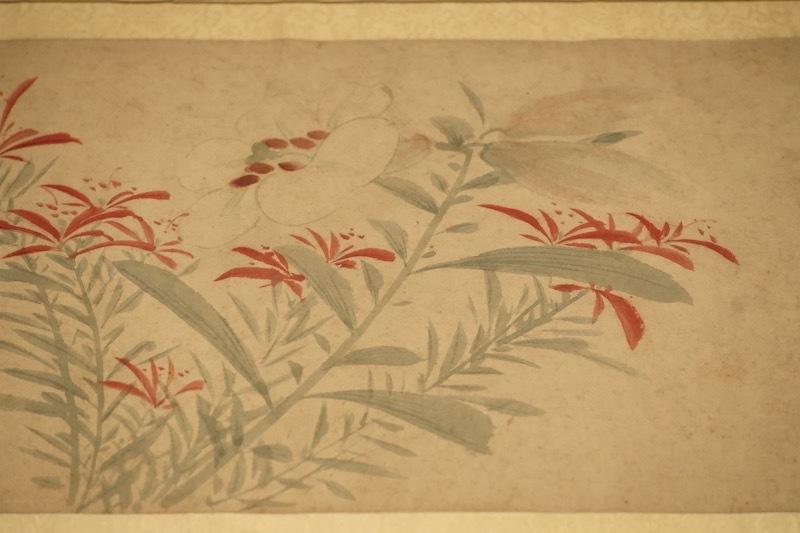

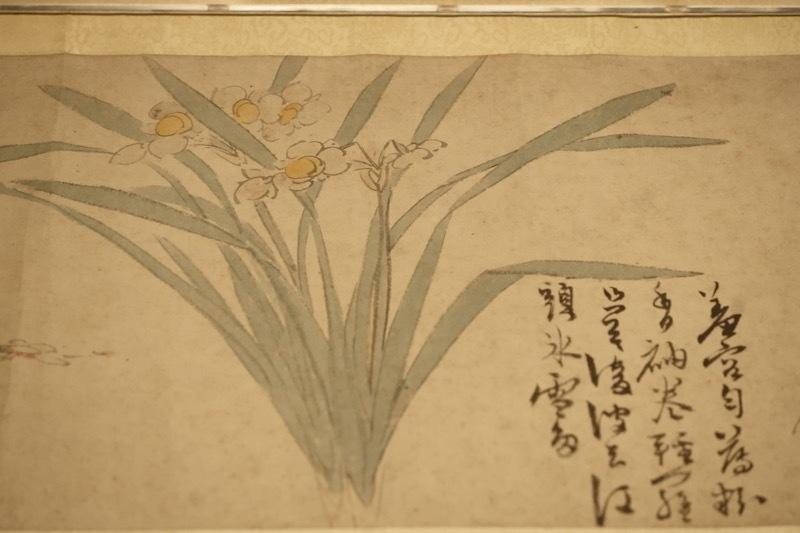

Chen Chun's "Flowers of the Four Seasons" scroll (partial)

Chen Chun's "Flowers of the Four Seasons" scroll (partial)

The beauty of garden flowers and trees is also an important element of landscape design. Chen Chun's "Flowers of Four Seasons" is a long scroll with horizontal layout and interlaced paintings and inscriptions. It depicts ten kinds of flowers in different seasons, including apricot flowers, magnolias, hydrangeas, roses, hibiscus, lilies, okra, chrysanthemums, narcissus, and plum blossoms. Each section of flowers is followed by a poem inscribed on the painting. The writing is bold and unrestrained, and the artistic conception of the poem enriches and deepens the connotation of flowers, which complements the painting.

What best reflects the interest of garden life are the various objects used in the garden, or "long objects". The tea cups, incense burners, vases, stationery, bronze and stone artifacts, and tripods and vessels on display all belong to this category.

Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu" scroll

Part of Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu" scroll

The specific aspects of garden life can be further perceived through Wen Zhengming's "Zhen Shang Zhai Tu" scroll. The scroll slowly unfolds from right to left. The first thing that comes into view is a group of tall and beautiful Taihu rocks. To the left are two thatched houses surrounded by pine, cypress and sycamore trees and a clump of bamboo. The wooden shelves on the right are filled with books and scrolls. On the left is a scene of two scholars sitting opposite each other at a table. The scholar facing the viewer places his hands on the unfolded scroll, and there is a paperweight on the table, as if he is preparing to unfold the scroll and appreciate it with his friends. There are also tripods, goblets, stone inkstones and book boxes on the tables on both sides, showing the owner's collection and hobbies.

Exhibition site

It is worth mentioning that the exhibition brings together treasures from five famous kilns, such as the Ru kiln celadon washbasin in the Palace Museum, the official kiln green glaze plate in the Tianjin Museum, the Ding kiln folded-rim washbasin in the Capital Museum, and the Jun kiln drum-nailed tripod washbasin in the Suzhou Museum. Looking at these porcelains with simple shapes and elegant glaze colors, they are not only highly consistent with the quiet atmosphere pursued by the garden space, but also reflect the abstract expression of the beauty of nature between their texture and light color. They are indeed a vivid portrayal of the ancients' concept of "using utensils to express the truth."

The transformation of Western gardens: from geometric axes to carrying individual emotions

Francis Bacon once said in his book On Gardening: “The beginning of civilization began with the construction of castles. But advanced civilization is inevitably accompanied by beautiful gardens.”

In the 18th century, with the spread of written descriptions of royal gardens such as the Old Summer Palace and the Summer Palace to the West, and the popularity of copperplate engravings in Europe, graphic and historical materials on Chinese garden art officially entered the vision of the European upper class. This formed a reference basis for Europe to understand Oriental garden art at that time, and also provided an important Oriental sample for the European garden innovation during the Enlightenment period, during the critical period when Baroque art was transitioning to Rococo style.

The "Anglo-Chinese garden" came into being against this background, replacing the symmetrical geometric axis with winding paths, freely growing trees, and oriental towers. Through "Kew Gardens: Pagodas and Bridges" created by Richard Wilson, the "Father of British Landscape Painting", we can sense the absorption and transformation of Chinese gardening concepts by the West at this time. Western gardens are no longer just symbols of power and rationality, but have become private spaces that carry personality, emotion and artistic conception. With the rise of romanticism, this new concept of nature gradually gained popularity and left a profound impact on the European literary and artistic circles in the 19th century.

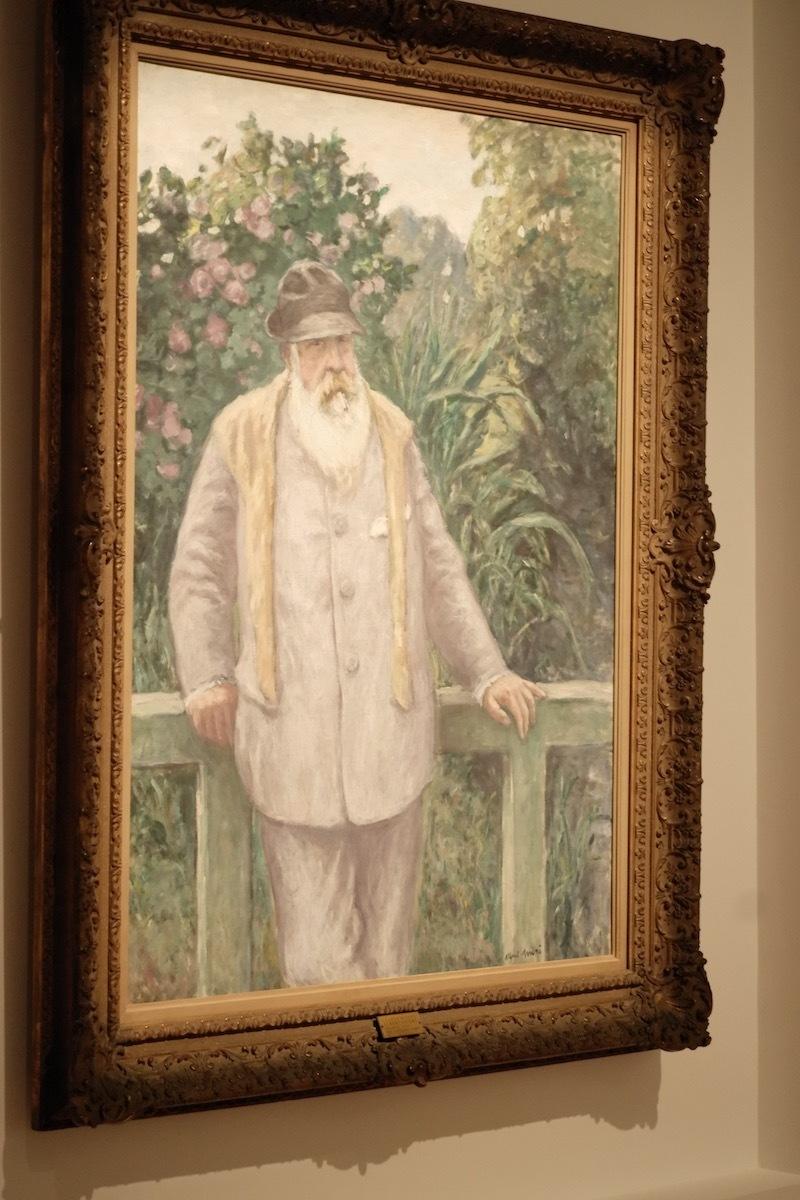

Claude Monet Portrait

Utagawa Hiroshige "One Hundred Famous Scenic Spots of Edo: Kameido Tenjin Territory"

In this era, French Impressionist master Claude Monet began his journey of garden construction. For him, the act of construction itself is not only to build a garden, but also an extension of painting practice. In 1883, he came across the small town of Giverny by chance and was attracted by the scenery there. Later, he rented a house in the local area, bought land one after another, settled there, and transformed the ordinary farmyard into a vibrant garden. Monet has always been fond of Oriental art and has collected a large number of Ukiyo-e prints, especially the works of Utagawa Hiroshige. The wooden arch bridge in "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Kameido Tenjin Neighborhood" had a profound influence on Monet, and he chose to reproduce this image in the waterscape of Giverny Garden.

He built a pond, introduced tributaries, and constructed a wooden arch bridge, which was quite similar in shape to the bridge in Hiroshige's prints. Water lilies were planted under the bridge, making it the visual core of the entire garden.

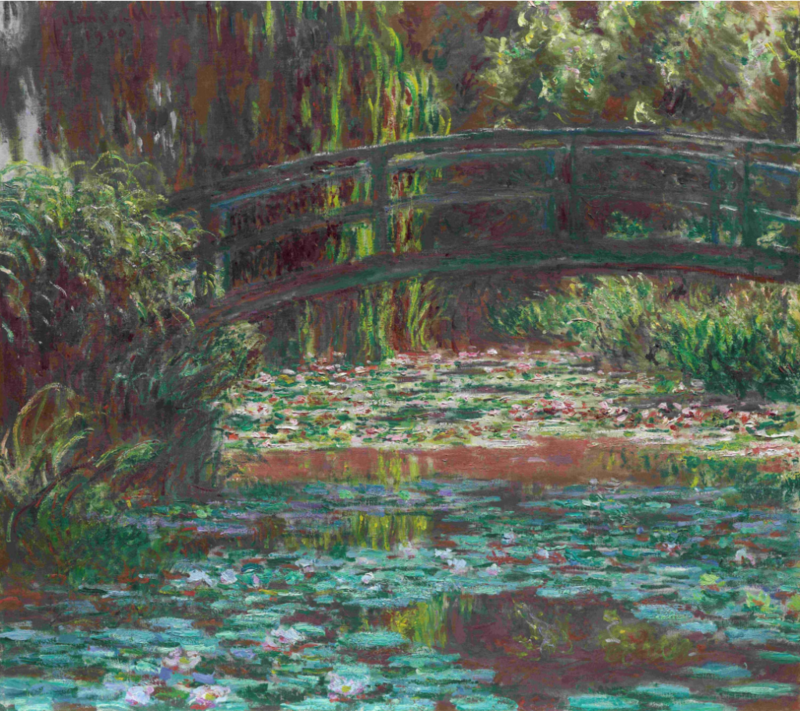

Monet's Water Lily Pond from the Art Institute of Chicago

The planting of water lilies not only enriches the water surface, but also provides endless changes in light and shadow, making the waterscape glow with different colors as time and weather change. In order to create a more oriental atmosphere, Monet also planted wisteria above the bridge. French writer Marcel Proust commented on this garden: "The colors have been adjusted and are wonderful; the tones have been formed and are harmonious and pleasing to the eye. This is not just a garden, but also art, a masterpiece drawn from life, full of vitality, and completed in nature."

Water Lily Pond from the Art Institute of Chicago

After the initial completion of the garden in 1895, it became Monet's experimental field for studying and exploring the relationship between light, shadow, color and nature. In the creative concept of Impressionism, the colors of sunlight, reflections and plants will all be different as the weather and time of day change. Monet understood this well and devoted all his energy to feeling and capturing these fleeting moments, and then freezing them on the canvas with his brush. In the two summers of 1899 and 1900 alone, he created 18 oil paintings with wooden bridges and ponds as the theme. The Water Lily Pond exhibited in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago is one of them. By the time he died in 1926, he left more than 200 paintings in Giverny Garden. This landscape created by his own hands has become the most enduring artistic masterpiece of Impressionism.

"So far, China and the West have demonstrated a tacit understanding that transcends time and space between the creation and reproduction of gardens. From Suzhou to Giverny, from Wumen landscape to Impressionist oil paintings, garden paintings have always been a concrete expression of the relationship between man and nature. Everyone's exploration and practice of gardens points to the same core, which is to reshape natural landscapes in an artistic way, integrate self-value pursuit, and ultimately make gardens a poetic habitat." Lu Wentao told The Paper.

It is reported that the exhibition will last until October 23. During the exhibition, Suzhou Museum will also launch more than 20 supporting educational activities, including 6 lectures, "Travel with Suzhou Museum" Suzhou Garden Series Study, Special Exhibition Theme Study Camp, Suzhou Museum Night School, Special Exhibition Reading, Hand-made Experience, etc. Visitors can view details and make reservations through the Suzhou Museum official website and mini program.

Click on the QR code below. Thank you for following The Paper (The Paper’s art column WeChat public account)