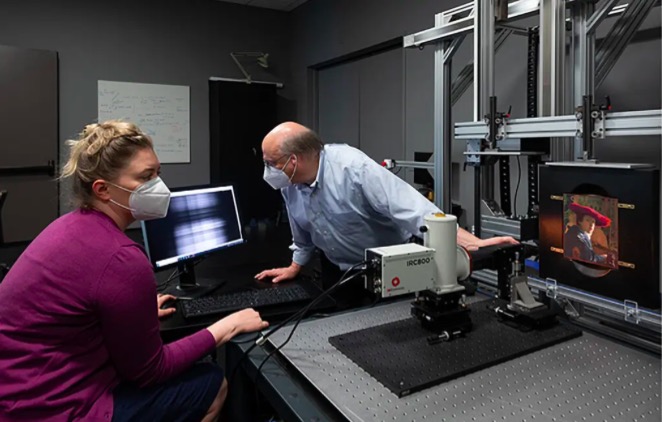

The National Gallery of Art in Washington has four paintings attributed to Vermeer, and over the past two years, researchers have brought these works into the laboratory, using technological imaging technology to see what the naked eye can't see, and have made new discoveries about Vermeer and his craft.

The Paper has learned that the National Gallery of Art in Washington recently opened a new exhibition "Vermeers Secrets", which includes "Woman Writing a Letter", "Woman Holding a Scale", "Girl with a Red Riding Hood" and "Girl with a Flute" Along with two 20th-century forgeries, the mystery of whether "Girl with the Flute" belongs to Vermeer is also revealed in the exhibition.

The Girl with the Flute (c.1665-1675) was removed from Vermeer.

Vermeer was one of the most important artists of the 17th century, but much of the Dutch painter's life and artistic practice remains a mystery.

There are only 36 known paintings of Vermeer in existence, so changing the attribution of a work can have a huge impact on the academic research and cultural programming built around the artist.

There is one less work attributed to Vermeer, but Vermeer is found to have a studio

For nearly half a century, scholars have questioned whether Vermeer actually painted The Girl with the Flute. Because of the same size, frame, wood, and paint, "Girl with a Flute" was once considered a companion to "Girl with a Red Riding Hood", and was often bundled and studied. But the rough brushstrokes and clumsy characters of "Girl with a Flute" make many people wonder if it was painted by the same artist.

After two years of research, the research team of the National Gallery of Art in Washington came to the conclusion that the painter who created "The Girl with the Flute" probably came from Vermeer's studio. He understood Vermeer's creative process, but could not master the technique.

"Science and technology show that the two painters used similar materials and painting styles, but treated them differently from the initial primer to the final finish," said Kathryn A. Dooley, an imaging scientist who worked on the project. Dooley) said.

Vermeer, The Girl with the Red Riding Hood, circa 1666-1667

Then another unknown was revealed - Vermeer had a studio.

Most scholars never considered that Vermeer might have had students or studio assistants, but new technical evidence bears this out.

After microscopic analysis of paint samples from The Girl with the Flute and The Girl with the Red Riding Hood, the research team found striking similarities. In both paintings, green earthy pigments are found in the shadows of the female faces. The use of this pigment to portray facial shadows in Dutch Golden Age paintings is highly unusual and not found in other works of Vermeer's contemporaries. It can be seen that the mysterious painter who painted "The Girl with the Flute" was familiar with Vermeer's unique methods and materials, but could not reach his professional level.

By contrast, The Girl with the Flute doesn't have the precision and control of The Girl in the Red Hat. But analysis of both works shows that they both used some of the same unique pigments and were probably created in the same studio.

Marjorie E. Wieseman, head of the Scandinavian painting department at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, worked with the research team to find possible explanations for the author of "The Girl with the Flute."

She reasoned that the enigmatic painter might have been a trained apprentice, a hobbyist who paid Vermeer to study, or even a member of Vermeer's family. Either way, it shows the existence of "Vermeer's Studio".

While the concept of the artist's studio is not surprising in the history of fine art, Vermeer was an important discovery, as he was long considered a solitary genius. Arthur K. Wheelock, the former head of the Scandinavian painting department at the National Gallery of Art in Washington and a Vermeer expert, believes that “Girl with the Flute” may have been created by two people, with Vermeer sketching it first. "I struggled with the attribution of the painting until the Vermeer exhibition in Washington in 1995, and it wasn't considered Vermeer," Wheelock added.

Part of "The Girl with the Flute"

Although The Girl with the Flute is currently out of Vermeer's name, there are still many unsolved mysteries. For example, who and under what circumstances painted the work?

Vermeer biographer Aneta Georgievska-Shine believes that "it is more likely that this work begins with Vermeer." Additional speculation by historians is that Vermeer His eldest daughter, Maria, became his secret disciple and completed several paintings after his death, including this "Girl with a Flute."

Vermeer was not a perfectionist, he had his moments of impatience

Technological advances have given museum research new tools to unearth hidden details in paintings dating back hundreds of years. Last year, the Dresden Collection in Germany completed the restoration of Vermeer's "Girl Reading a Letter by the Window ," and saw the image of Cupid in the background, possibly painted by another artist.

Another revelation at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., is that Vermeer was not always a painstaking, slow-drawing perfectionist. Through the controlled and polished surfaces of the paintings, it can be seen that Vermeer was more impetuous and impatient than he had imagined.

Vermeer, Woman Holding a Scale, 1662-1663

For example, a microscopic analysis of the layers of pigment beneath the surface of "Woman with a Balance" shows that Vermeer began painting with a monochrome sketch and then quickly painted colors, patterns and shapes of light on the base. Further imaging revealed that Vermeer added a copper-containing material to speed up the drying of the black pigment to speed up the painting process.

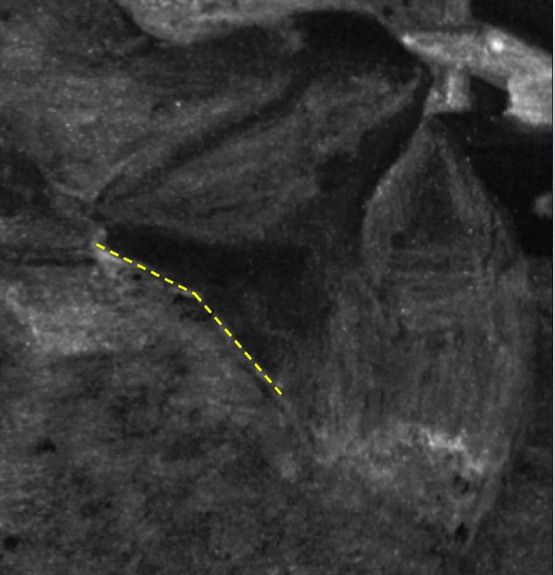

The tablecloth in "Woman with Scales" changes with Vermeer's creation. The light color above shows the association of the black pigment in the primer, where the swiftness and freedom of the brushstrokes can be seen. The yellow line marks the change in the tablecloth, and the image below shows Vermeer finishing the work with more detailed brushstrokes and straightening the fold.

Also, Vermeer sometimes continued to paint over other paintings. Back in the early 1970s, researchers learned in images that Vermeer painted The Girl in the Red Riding Hood over an unfinished Portrait of a Man in a Black Hat, and that the portrait of the man may have been painted by another artist. of. Vermeer didn't scrape the image or overwrite the layer, just rotated the image 180 degrees and went straight to the drawing.

Digital imaging shows "The Girl in the Red Hat" with a "Portrait of a Man in a Black Hat" underneath.

Advances in imaging technology over the past 20 years have allowed researchers to see portraits of men more clearly than ever before. In the absence of written records, these non-invasive techniques have given researchers a glimpse into how Vermeer worked and clues to the characters he depicted. One day, we might even be able to identify the invisible "Black Hat" -- or his author.

Modern technology imaging enables a clearer view of the artist's work process and identifies subtle changes.

Vermeer, The Woman Writing a Letter, circa 1665

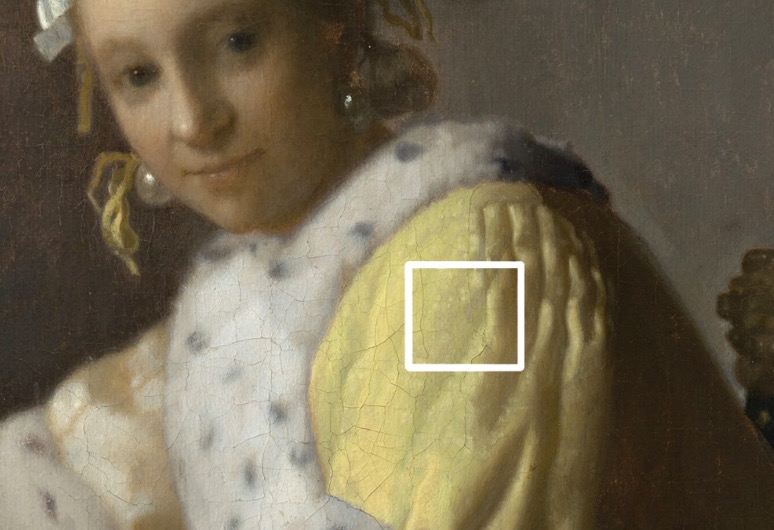

Observing the sleeves of the yellow coat of "The Lady Writing a Letter", we can see Vermeer's meticulous use of paint. Analysis of pigment samples obtained by imaging revealed that Vermeer used four types of yellow pigments in The Lady who wrote the Letter: two different lead-tin yellows, as well as yellow ochre and lake yellow (tartrazine), which was later used in cosmetics. , culminating in a rich and complex yellow that was Vermeer's thoughtful creation.

Vermeer's "The Woman Who Writes Letters" (detail)

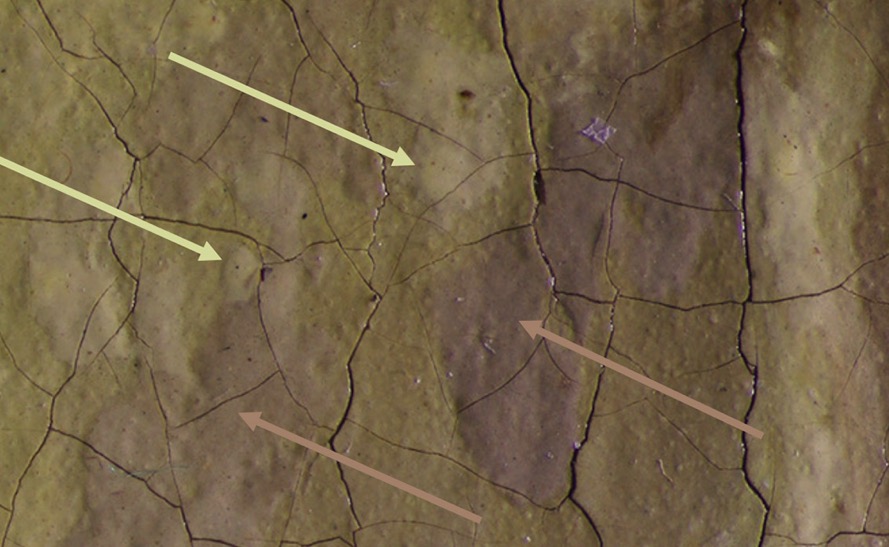

The arrows point to the use of at least 4 shades of yellow on the sleeves of The Lady Who Writes the Letter.

Observation of Lady Writing a Letter using infrared reflectance imaging spectroscopy, a technique that helps visually separate paint pigments, reveals that Vermeer had drawn the quill in a more vertical position to suggest the speed of his writing. Using the same technique, the researchers saw that the scale in Vermeer's "Woman with a Scale" was initially angled, before placing the plates on both ends of the scale parallel to achieve perfect balance.

Using infrared light to penetrate the surface reveals how Vermeer initially placed the scale in "Woman with a Balance", which is different from what is seen in later completed works.

But it's one thing to attribute it to an error, it's another to be a fake.

In the "Vermeer fever" atmosphere of the 1930s, Andrew W. Mellon purchased two paintings - "The Lacemaker" and "The Smiling Girl" - and entered the Washington State in 1937 Collection of the art gallery.

Critics questioned when they first saw the two works. The stiff figure, clumsy brushwork, and flaws in anatomical proportions are clearly not Vermeer's breath.

Imitation of Vermeer, "The Smiling Girl" (right), "The Laceworker" (left), circa 1925

Recent scientific analysis confirms the suspicions. Testing of the colour elements revealed the presence of synthetic ultramarine blue (a pigment only introduced in the 19th century) and lead chromate (a yellow pigment first produced in 1811).

The putative forger, Theodorus van Wijngaarden, was born in 1874, 200 years after Vermeer's death. He uses sun exposure to accelerate the cracking of the picture, imitating the old color-changing varnish and coloring to achieve the "old" effect.

A study of Vermeer's work by researchers at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. using the latest technology.

Although "The Girl with the Flute" is now out of Vermeer's name, it is still expected to go on view at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam next year, in what will be Vermeer's largest exhibition to date. The National Gallery of Art in Washington does not intend to remove it from the public eye.

"It's a nice painting," Wieseman says, and it's a reminder of how museum research is constantly changing our view of the past. While details about Vermeer's life are currently unknown, new research helps us understand the artist and his remarkable work.

Note: The exhibition will run until January 8, 2023. This article is compiled from the website of the National Gallery of Art in Washington and reports by art reporter Zachary Small.