As is well known, the Tang Dynasty poet Wang Wei, whose courtesy name was Mojie, originated from the Buddhist scripture *Vimalakirti Sutra*. Looking at the artistic evolution of sutra illustrations, the image of Vimalakirti began with the works of Gu Kaizhi in the Eastern Jin Dynasty, with the earliest existing example in Bingling Temple. It developed in the Longmen Grottoes, matured in the Dunhuang Grottoes and in famous Song and Yuan Dynasty paintings, showcasing a rich tapestry of diverse cultural influences. However, the most moving spiritual core of the *Vimalakirti Sutra* remains the ordinary life and prajna wisdom displayed by Vimalakirti, especially his image of "unimpeded eloquence, unobstructed wisdom, and playful supernatural powers," which has deeply penetrated the consciousness of Chinese literati and officials, and is regarded as the embodiment of an ideal personality.

The Vimalakirti Sutra records that Vimalakirti came from the Eastern Land of Abhirati, was an emanation of the Tathagata Golden Millet, and lived in Vaishali. He assisted the Buddha's educational work as a layperson, essentially a teaching assistant. Vimalakirti had children and a harmonious, happy family. This seemingly ordinary wise man could "reach the entire universe in his hands and hold the masses in his grasp," freely entering and leaving the Buddha's worlds, enjoying delicious food, and displaying supernatural powers, completing his lessons amidst the astonishment of his audience, much like a magician performing a trick.

The image of Vimalakirti, with his "unimpeded eloquence, unhindered wisdom, and playful supernatural powers," has deeply penetrated the minds of Chinese literati and officials. In addition to Wang Wei, Fu Dashi, Bai Juyi, Wang Anshi, Su Shi, Huang Tingjian, Yelü Chucai, Lin Zexu, and others often regarded Vimalakirti as the embodiment of an ideal personality, praising his spiritual freedom and transcendence.

Metaphor: Illness and the Game of Visiting the Sick

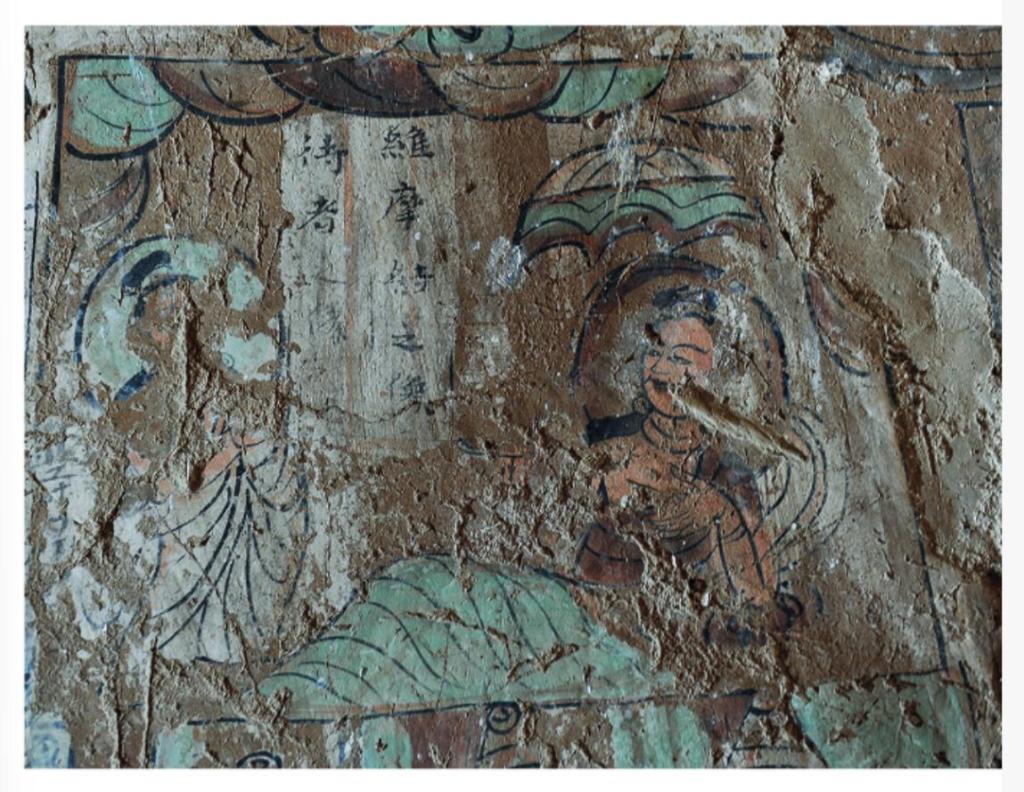

In the second year of Xingning (364) of the Eastern Jin Dynasty, the Waguan Temple in Nanjing was first established. The great painter Gu Kaizhi painted an image of Vimalakirti in the small hall north of the temple. "After the painting was completed, its brilliance shone for several days." This is the earliest known image of Vimalakirti, but it no longer exists. The earliest known surviving image of Vimalakirti is found in Cave 169 of Bingling Temple, sculpted and painted during the Western Qin Dynasty. Two examples are found: one in niche 10; the other in niche 11, inside a rectangular curtain. He has a high bun, long hair flowing over his shoulders, his upper body half-naked, and he is reclining on a couch, showing signs of illness. Above his head, beside him, is the inscription "Image of Vimalakirti." Residing in a curtain, with a beard, and lying down, he is the standard for Vimalakirti images.

Image of Vimalakirti in Niche No. 11 on the north wall of Cave 169, Bingling Temple

In the Vimalakirti Sutra transformation paintings at Yungang Grottoes, there are various framed, single-framed, and multi-framed compositions. There are currently 58 Vimalakirti Sutra transformation paintings in Mogao Grottoes. Among them, the Vimalakirti Sutra paintings in Caves 103 and 220 adopt a symmetrical composition with the two monks sitting and discussing the Dharma, which has typical comparative significance. The Vimalakirti in these two caves is exactly the same in terms of clothing, sitting posture and expression.

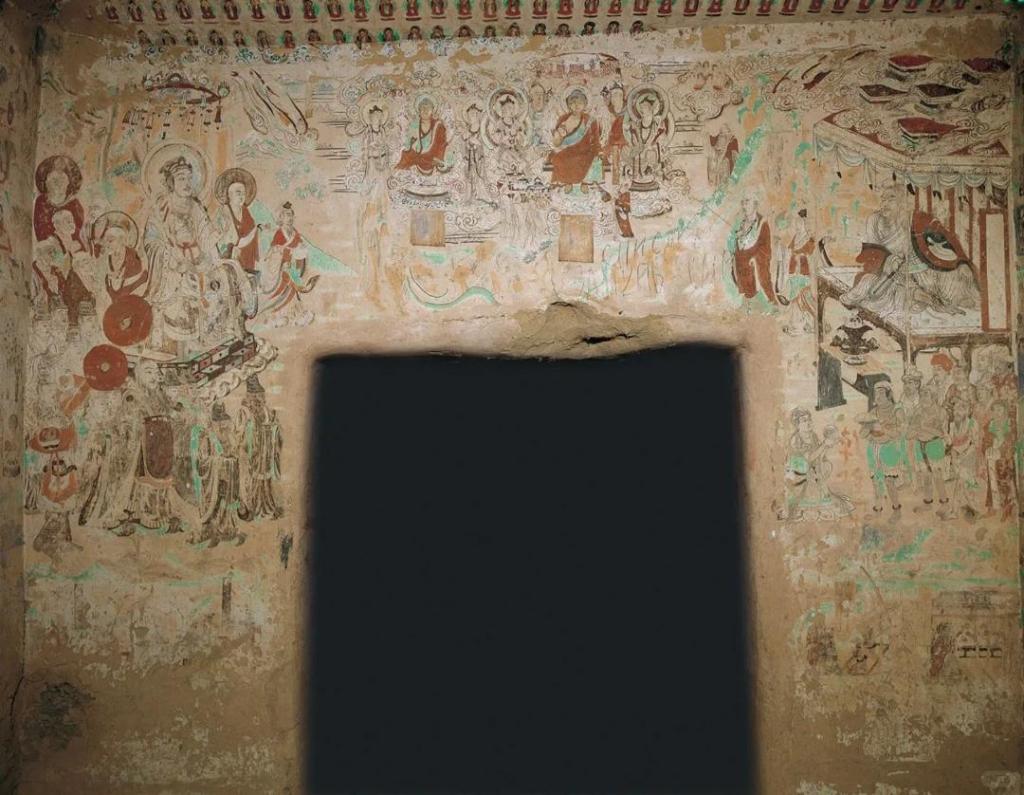

Mogao Grottoes Cave 103, High Tang Dynasty, Vimalakirti Sutra Transformation

The Vimalakirti Sutra mural in Mogao Cave 103, created during the High Tang Dynasty, is the most famous and continues to be copied to this day. Vimalakirti sits casually on his bed, surrounded by figures of various postures. These figures, representing ethnic minorities and foreign envoys traveling along the Silk Road, depict the procession from the Vimalakirti Sutra who accompanied Manjushri Bodhisattva to visit Vimalakirti in his illness: eight thousand Bodhisattvas, five hundred Arhats, hundreds of thousands of Devas, and humans, all dressed in different styles and remarkably lifelike. This demonstrates how Tang Dynasty Dunhuang artists naturally integrated the figures traveling along the Silk Road with those from the sutra. Above the bed is a throne amidst auspicious clouds, a contextualized representation of the scene in the Vimalakirti Sutra where "Vimalakirti feigns illness, and Manjushri visits him": "From delusion arises attachment, and thus my illness arises. Because all sentient beings are sick, therefore I am sick. If all sentient beings were free from illness, then my illness would cease."

The Buddha Kingdom in the Palm of Vimalakirti's Hand in the Upper Right of Cave 103, Mogao Grottoes

Compared to the perfectly enlightened, all beings in the world are sick. Bodhisattvas, for the sake of all sentient beings, are born and die; having birth and death means being sick. The scriptures use metaphors to illustrate the shared nature of saints and ordinary people: like parents and their only child. When the child is sick, the parents are worried and distressed; when the child recovers, the parents are at peace. The scriptures also use analogical logic to explain the close, interdependent relationship between Bodhisattvas and sentient beings. A Bodhisattva's illness arises from great compassion. Illness symbolizes both the importance of physical and mental health and the inseparable bond between Bodhisattvas and all sentient beings.

Above Vimalakirti's seat are five high and broad thrones, the artist using auspicious clouds to accentuate their solemnity, depicting a meaningful story from the scriptures: Sariputra worried that the accompanying bodhisattvas would have no seats, but Vimalakirti immediately knew this and questioned Sariputra: "Why do you come for the Dharma, yet you seek thrones?" Vimalakirti, like a machine gun, directly addressed Sariputra: "In all things, one should seek nothing." When he heard Manjushri, the Bodhisattva foremost in wisdom, describe the most ornately decorated thrones at the Buddha Sumeru Lamp King in the Land of Sumeru, he immediately displayed his supernatural powers, his mind reaching supernatural realms. The Buddha Sumeru Lamp King then sent 32,000 lion thrones, instantly making the room vast and solemn, able to accommodate 32,000 lion thrones without any obstruction, even in the city of Vaishali, without feeling cramped. Many sutra illustrations retain this detail, demonstrating the wisdom of unobstructed expanse and seamless integration of the subtle and the profound.

Mogao Cave 103, High Tang Dynasty, Vimalakirti Sutra Transformation

Mogao Cave 103, High Tang Dynasty, a variation of the Vimalakirti Sutra with a left-right structure.

The illness is not real, nor is the visitation of the sick. A single thought can give rise to illness, and the act of visiting the sick is a game played by Vimalakirti, the Buddha, and Manjushri. Wang Anshi also wrote "Ode to the Vimalakirti Image," a poem that can be considered the fundamental principle for understanding all Buddhist sculptures:

The body and the image are not two separate things. All Buddhas of the three times are also like this image.

If you seek the truth, it becomes illusion. You should offer incense and flowers in this way.

Oneness: The Tacit Understanding Between Vimalakirti and Manjushri

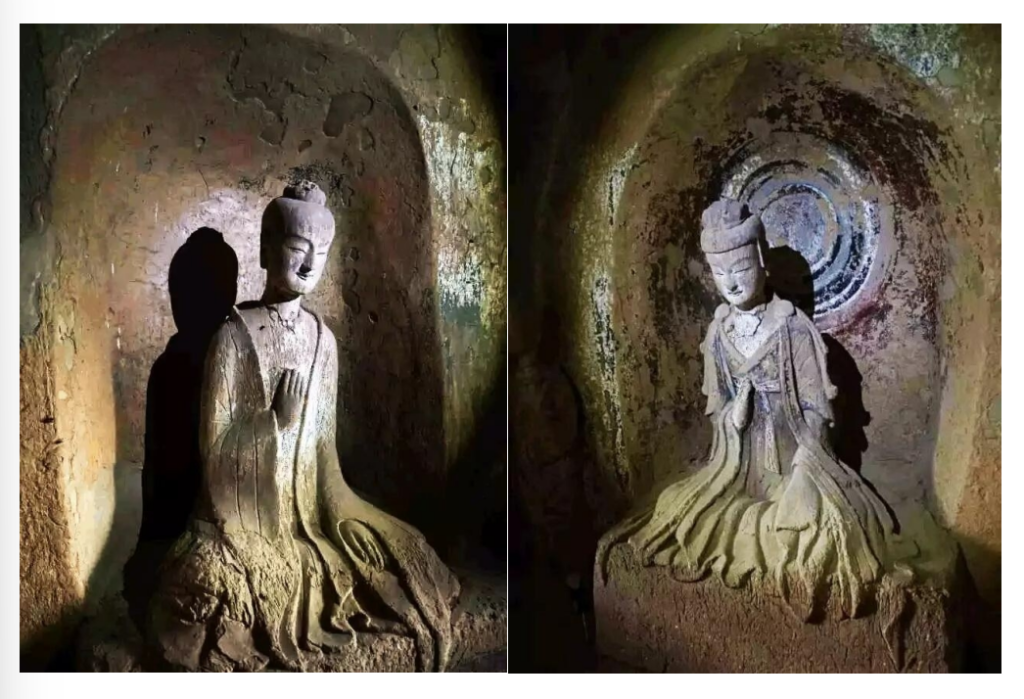

Cave 123 at Maijishan Grottoes, carved during the Western Wei Dynasty, is also the cave depicting the Vimalakirti Sutra. Vimalakirti and Manjushri Bodhisattva are seated in a lotus position, engaged in a debate. Manjushri is 1.20 meters tall, wearing a crown, with downcast eyes, a belt around his waist, and his robes flowing naturally. His right hand is raised, while his left hand rests casually on his lap, and he is adorned with concentric halos. Vimalakirti is 1.22 meters tall, with his hair in a small topknot, wearing a wide outer robe, his left hand on his lap, and his right hand raised to his chest. This is the unique feature of Cave 123 at Maijishan Grottoes—Manjushri and Vimalakirti appear to be the work of the same artist. Their unity is sculpted with remarkable realism and clarity; their inner spirit is highly consistent, as if they were two sides of the same coin, reminiscent of the shared theme in the dialogue between Manjushri and Vimalakirti in the sutra.

Vimalakirti and Manjushri Bodhisattva in Cave 123 of Maijishan

The Vimalakirti Sutra murals in the side niches of the front corridor of Cave 4 at Maijishan Cave are very adept at using the scenery to create a sense of grandeur. They boldly treat the seven adjacent caves of Cave 4 (Sanhualou), which were carved during the Northern Zhou Dynasty, as the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in attendance. Vimalakirti, the layman in the left niche, silently faces Manjushri Bodhisattva above the right niche, separated by the magnificent array of Cave 4. This way of dialogue across space, facing the vast Qinling Mountains and all living beings, makes people feel the truth of Yu Xin's article: "In such a dusty wilderness, a hall for preaching is opened, just as in Xiangshan, a Buddha dwelling in peace is faced."

Vimalakirti and his attendants in the left side niche of the front corridor of Cave 4 at Maijishan Grottoes

Today, I visited several paintings and found that the Vimalakirti in the left niche of the front corridor of Cave 4 at Maijishan Grottoes bears a striking resemblance to the Vimalakirti in Caves 103 and 220 of Dunhuang, as well as the "Vimalakirti Teaching" painting in the Palace Museum, the "Vimalakirti Painting" in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, the "Vimalakirti Non-Dualism" painting by Wang Zhenpeng of the Yuan Dynasty in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the "Vimalakirti Painting" in the Tofukuji Temple. They all share a similar appearance: robes and headscarves, leaning forward, one hand on their knee, the other holding a whisk, their eyebrows and beard bristling, their eyes piercing. Chinese art emphasizes capturing the spirit; whether in paintings or sculptures, these works accurately convey the spirit of Vimalakirti: ordinary yet living, compassionate yet wise.

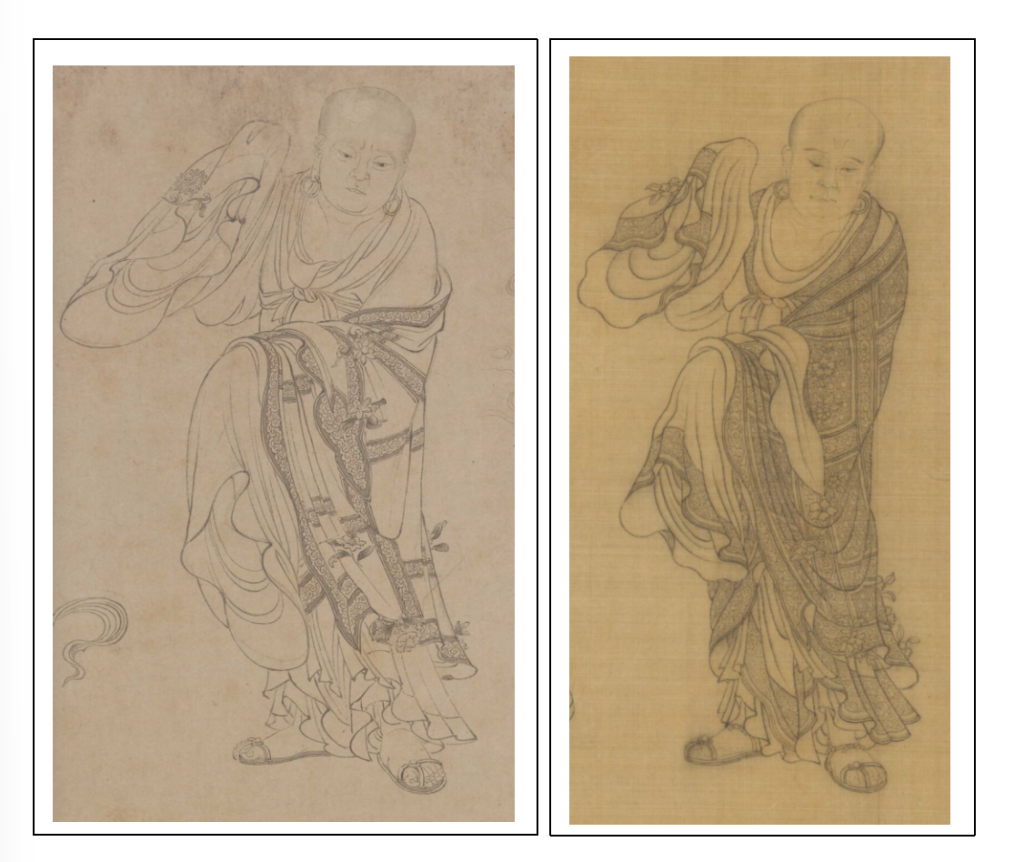

A partial view of the Vimalakirti Sutra painting attributed to Li Gonglin (attributed to Li Gonglin) from the Northern Song Dynasty, now in the Palace Museum.

Vimalakirti Sutra Transformation Scene on the South Side of the East Wall of Cave 220

Although the "Vimalakirti Sutra" and "Vimalakirti Non-Dualism" paintings are from different eras and are now in different exhibition halls, they are exactly the same in terms of structure and figure setting. The only differences are that Manjushri Bodhisattva's face is different, one without a beard and the other with a beard; Shariputra's robe is different, one with light coloring and the other with dark coloring; and Skanda Bodhisattva's expression is different, one young and strong and the other old. It can be seen that there are kindred spirits across generations, and artists of all generations admire and follow in the footsteps of each other, paying tribute to the masterpieces of the past through imitation.

Shariputra in the Vimalakirti Sutra and Shariputra in the Vimalakirti Sutra

Manjushri Bodhisattva seems to be a reporter who is good at asking questions, interviewing the person involved from various aspects, such as "How can the patient subdue his mind?" Vimalakirti talked about several attitudes towards illness, among which "to receive all suffering without receiving any suffering" is the most crucial, which can be described as the transcendent concept of coexisting with illness.

The narrative element in sutra illustrations varies, some strong, some weak. For example, both the *Vimalakirti Sutra Expounding the Teachings* and the *Vimalakirti Non-Dualism* depict Shariputra, whose clothes are adorned with flowers that won't fall off, positioned between Vimalakirti and Manjushri. However, in the *Non-Dualism* illustration, Shariputra lacks his long eyebrows and appears quite young. Contrasting with the beautiful celestial maiden, they resemble a pair of bickering friends: Shariputra, disgusted by the flowers, tries to shake them off, and the maiden immediately points out his discrimination and attachment. Shariputra even adopts the celestial maiden's female identity, to which the maiden replies that in her twelve years there she has seen neither men nor women, only the Dharma. The maiden then displays her supernatural powers, transforming herself into a man and Shariputra into a woman. These events are like playful banter between male and female classmates in a classroom—mischievous and amusing.

The Buddha in the Palm of Your Hand in Mogao Grottoes Cave 9, a Transformation of the Vimalakirti Sutra

In Mogao Grottoes Cave 103 and Cave 9 (late Tang Dynasty), Vimalakirti's right palm appears to open a computer screen, displaying the solemn purity of the Land of Abhirati and Akshobhya Buddha. Vimalakirti holds the inhabitants and palaces of the Land of Abhirati in his hand, like a potter shaping clay, as if holding a garland of flowers, displaying them in this world, much like how we use AI to replicate parts of the Dunhuang grottoes in other cities. The images are all clearly discernible: Asuras stand in the middle of the ocean, holding the sun and moon in their hands, with Mount Sumeru above their heads, two dragons coiled around its waist, and a giant ladder on the right connecting the mortal realm with the heavens, on which six mortals are climbing. Most wonderfully, although the Land of Abhirati has entered this world, it has neither increased nor decreased, nor has it become cramped, remaining unchanged, just as Mount Sumeru can be contained within a mustard seed. Wang Anshi recorded his insights from reading the Vimalakirti Sutra on several occasions: "The body is like foam and wind, cut by a knife and perfumed with perfume, all vanish. Sitting in meditation in the world, one observes this principle; Vimalakirti, though ill, possesses supernatural powers." The world of emptiness still holds immeasurable wonders, inspiring boundless faith in one.

The Vimalakirti Sutra transformation mural in Cave 61 of Mogao Grottoes.

Mogao Cave 61, originally named Manjushri Hall, features a mural of the Vimalakirti Sutra on its east side: the chapter on the Buddha's Land above the door; Manjushri to the south and Vimalakirti to the north, also in a framed structure. The Vimalakirti Sutra mural in Mogao Cave 98 is 2.95 meters high and 12.65 meters wide, covering a total area of approximately 37.3 square meters, making it the largest Vimalakirti Sutra mural in Mogao Caves. This massive mural depicts eight chapters of "Expedient Means" above the cave entrance, creating a cohesive and vivid depiction of daily life. Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, is relegated to a secondary position, highlighting Vimalakirti's wisdom and elevating his image. The Prajna wisdom of emptiness and existence, and the wondrous existence within emptiness, emerges in the dialogue between Vimalakirti and Manjushri.

The dialogue between Manjushri and Vimalakirti is the theme of these sutra illustrations and the core of this sutra. Witty and agile, every sentence points to the truth. Su Shi wrote "Ode to Shi Ke's Painting of Vimalakirti," praising the painter: "He can make Vimalakirti appear from the tip of his brush, his divine power surpasses even Vimalakirti's. If one says this painting has no real form, then the city of Vaishya is also not real." The mind of the writer and the mind of the painter are both of the same wondrous mind.

The Art of Speaking and Not Speaking

In his later years, Bai Juyi compared himself to Vimalakirti and wrote a poem entitled "Self-Eulogy":

The white-robed hermit and the purple-spirited immortal, half-drunk, singing and half-sitting in meditation.

Today Vimalakirti drinks wine, but back then, Qiji didn't ask for money.

Guests are casually entertained by the pond, and music is played before the lamps for any occasion.

But whether this body can be sold or not, the seasons and flavors are irrelevant.

With a transcendent wisdom, he navigated worldly life with ease, even transcending it—this is why scholars and officials revered Vimalakirti. In the *Vimalakirti Sutra*, Vimalakirti clarified many philosophical questions, such as:

The Non-Dual Dharma Gate: Afflictions are Bodhi, birth and death are Nirvana; the worldly and the transcendent are not two; the non-dualistic view is the key point of this sutra. Manjushri asked, "How does one enter the non-dual Dharma Gate?" Vimalakirti, who loved debate and was a super "roaster," actually remained silent, sitting quietly! In Vimalakirti's silence, the pure source is revealed, which is the first principle, the true reality, transcending language and thought, transcending all concepts, transcending duality, transcending all forms, and is essentially empty.

When the mind is pure, the Buddha-land is pure: the Pure Land is in the mind, the Pure Land is in the present moment; "If a Bodhisattva wishes to attain the Pure Land, he should purify his mind; as his mind is purified, the Buddha-land is purified." The Pure Land is not in an external space, nor is it in the West, but in the pure mind of the present moment.

Life itself is a training ground: whether in a tavern or a street corner, or by chance, everything becomes a classroom for Vimalakirti. Life is a school, and everything is a classroom. The training ground is everywhere; there is no need to live in seclusion. Daily life is the crucible for tempering one's mind and understanding.

Vimalakirti painting by an anonymous Song dynasty artist

Influence

The Vimalakirti Sutra, one of the seven sutras of Zen Buddhism, significantly influenced the spiritual structure of Chinese literati. Its essence—avoiding extremes and practicing Prajna (wisdom)—can be succinctly summarized as a transformation of the Vimalakirti Sutra. Within the existing discourse system of Chinese culture, it is easily understood and accepted, and is frequently discussed. Wang Anshi once used his poem "North Window" to record his reading of the Vimalakirti Sutra in his later years:

When ill or frail, one should always be strong and supportive, and even chickens and bellflowers are sometimes necessary.

The roots of an empty flower are hard to find and pluck; the smoke and dust of a dream are hard to sweep away.

The medicine bag of the elders may or may not exist, and the classics of Xuanyuan may or may not exist at all.

A warm spring breeze caresses my pillow by the north window as I leisurely read several volumes of the Vimalakirti Sutra.

Vimalakirti's silent expression profoundly influenced Zen Buddhism. "Silence" does not mean "not preaching," but rather "preaching," "speaking without words," breaking free from attachment to language and conveying Zen wisdom beyond words. When Emperor Wu of the Liang Dynasty invited Fu Dashi to preach, Dashi remained silent, then struck the table with a ruler and rose from his seat. Emperor Wu was momentarily astonished, and Zen Master Zhigong declared, "Dashi's preaching is finished." Thus, Zen Master Zhigong and Fu Dashi respectively played the roles of Manjushri and Vimalakirti. The absence of words and language is the true non-dualistic Dharma.

Hongzhi Zhengjue of the Song Dynasty advocated Silent Illumination Chan. Silent means sitting in meditation; Illumination means observing with wisdom. You see, Silent Illumination Chan and the silent sitting opposite each other in the Vimalakirti Sutra are actually of the same lineage.