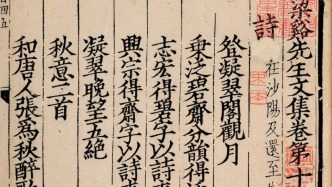

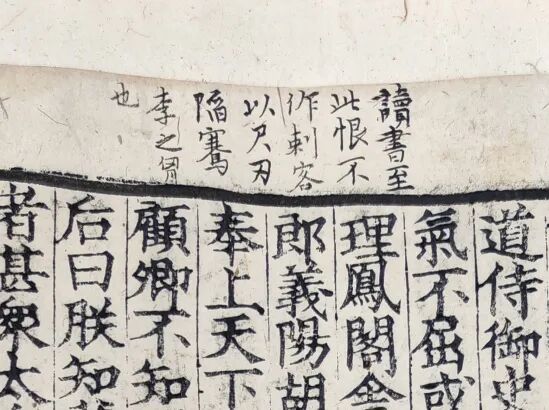

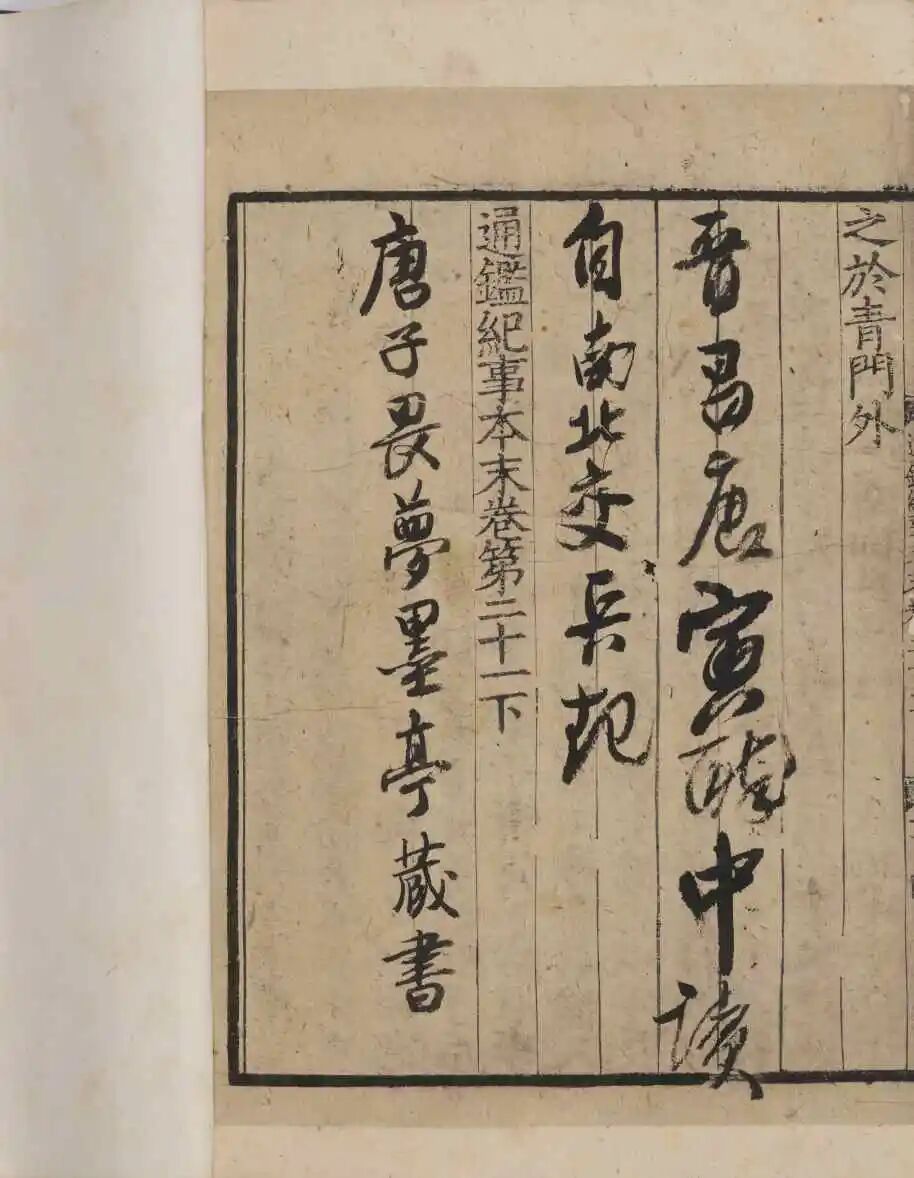

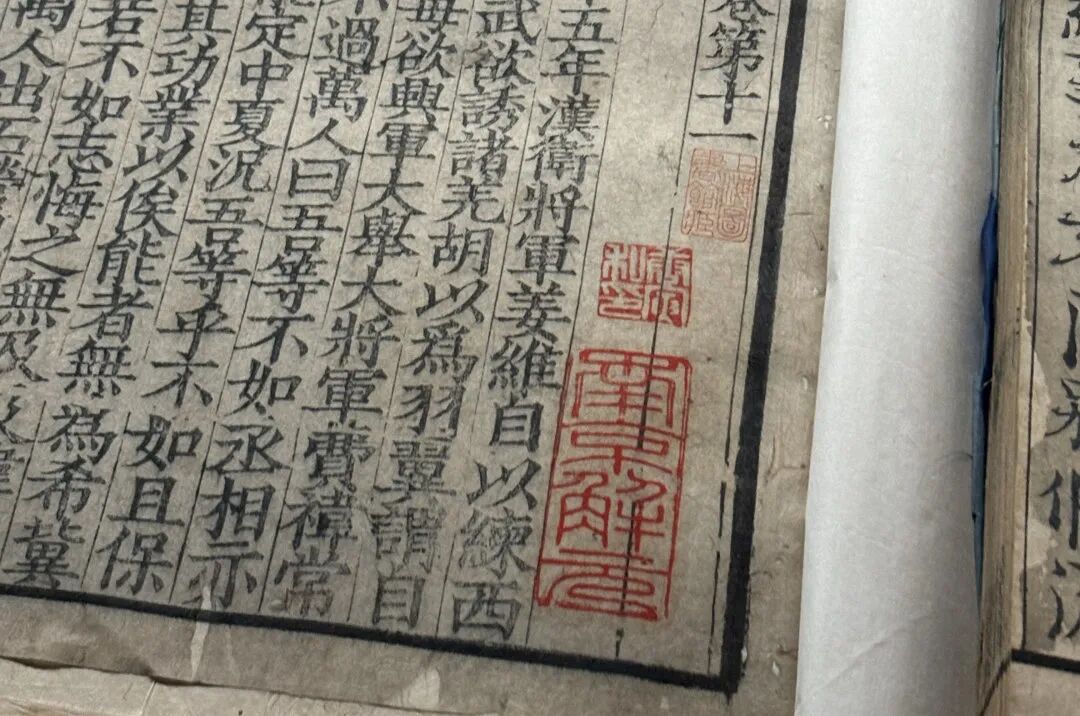

The Paper learned that a Song Dynasty woodblock print edition of *Tongjian Jishi Benmo*, treasured by Tang Bohu, is on display at the Shanghai Library's annual major collection exhibition, "Inheriting the Beauty of Antiquity: The Suzhou Pan Family Classics and Documents Collection of Shanghai Library." Tang Bohu's meticulously copied marginal notes and spontaneous handwriting offer a glimpse into the "thoughts" of this renowned scholar from Jiangnan while reading. The most intriguing annotation appears at the end of volume twenty-one of *Tongjian Jishi Benmo*: "Tang Yin of Jinchang read this in a drunken stupor, beginning with the war between the North and South." Imagine Tang Bohu in the Dream Ink Pavilion of Peach Blossom Hermitage, drinking and reading, and when inspired, he would write freely and unrestrainedly.

portrait of Tang Bohu

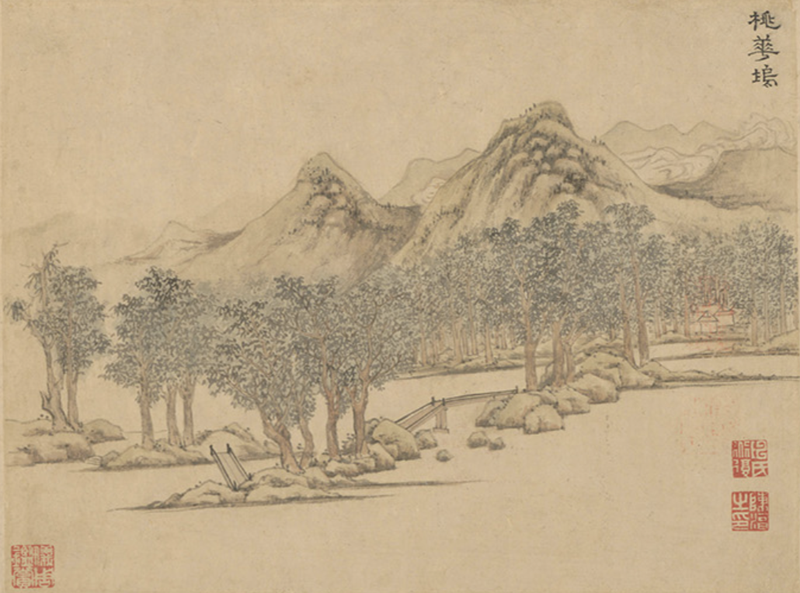

The person fishing in "Peach Blossom Dock on the Lake" in Tang Yin's "Fishing Retreat in Huaxi" is likely the painter himself.

Tang Yin (1470-1523), courtesy name Bohu, also known as Ziwei, and with other pseudonyms such as Liuru Jushi, Taohua Anzhu, Lu Guo Tang Sheng, and Tao Chan Xian Li, was a native of Suzhou and one of the "Four Great Talents of Jiangnan." A renowned calligrapher, painter, and writer of the Ming Dynasty, Tang Bohu was proficient in poetry, lyrics, and prose, and possessed exceptional talent in painting and calligraphy. However, Tang Bohu also had a hidden side—a "scholarly genius" who loved collecting books, reading, and writing annotations.

Write down the interesting anecdotes.

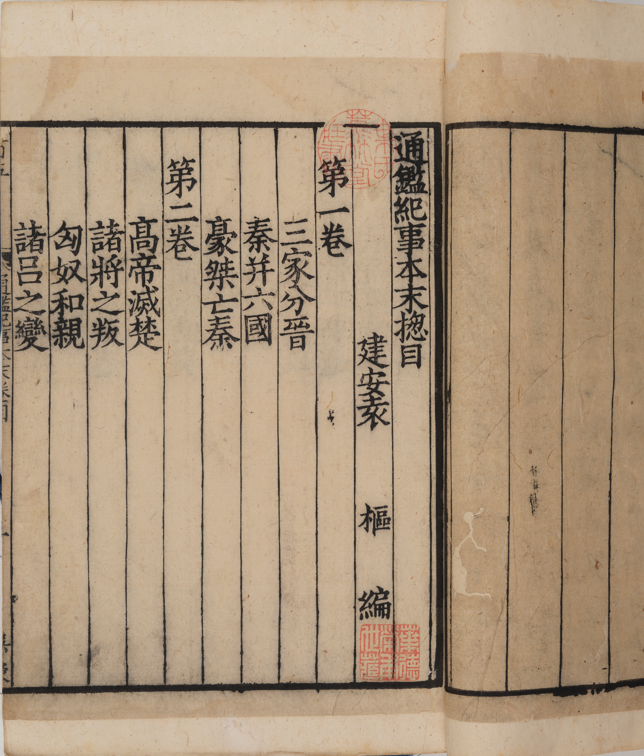

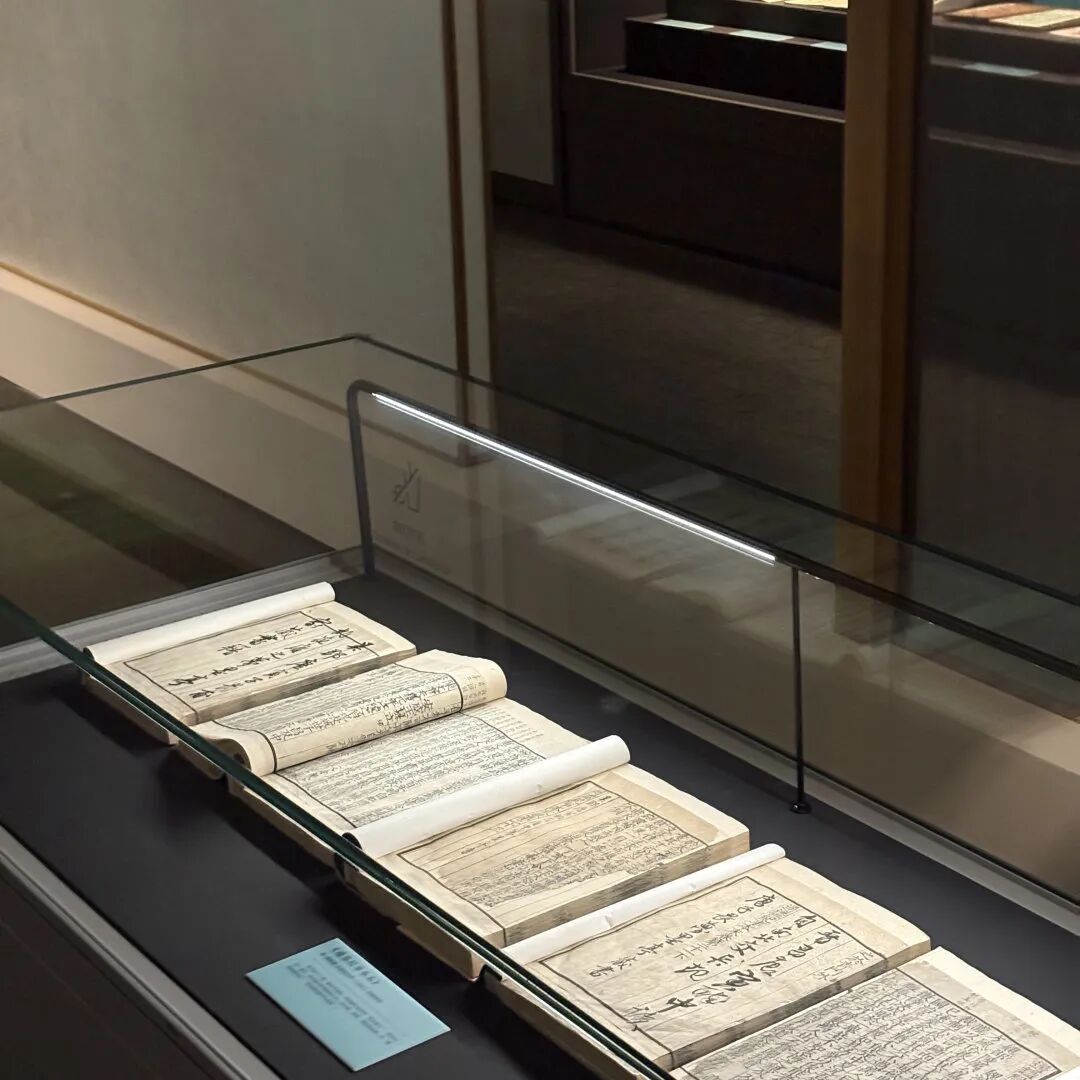

According to information released by the Shanghai Library, *Tongjian Jishi Benmo* is China's first historical work written in the style of a chronicle, compiled by Yuan Shu, a historian of the Southern Song Dynasty. The book comprises forty-two volumes, modeled after Sima Guang's annalistic history, *Zizhi Tongjian*, selecting historical events from the Warring States period (the division of Jin into three states) to the Five Dynasties period (the conquest of Huainan by Emperor Shizong of the Later Zhou Dynasty) as independent chapters. This type of history, centered on "events," possesses both historical value and literary readability, thus enjoying widespread popularity.

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

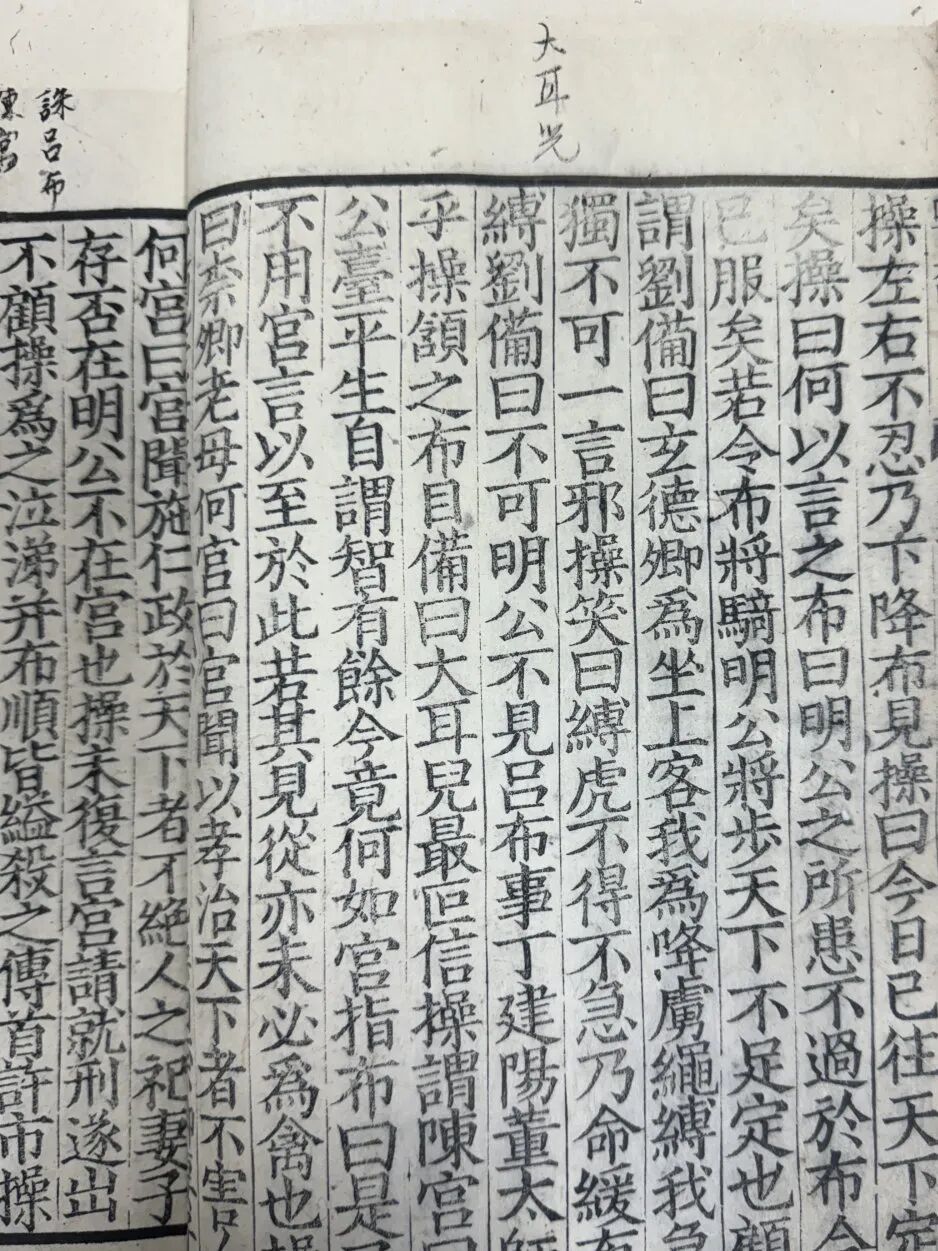

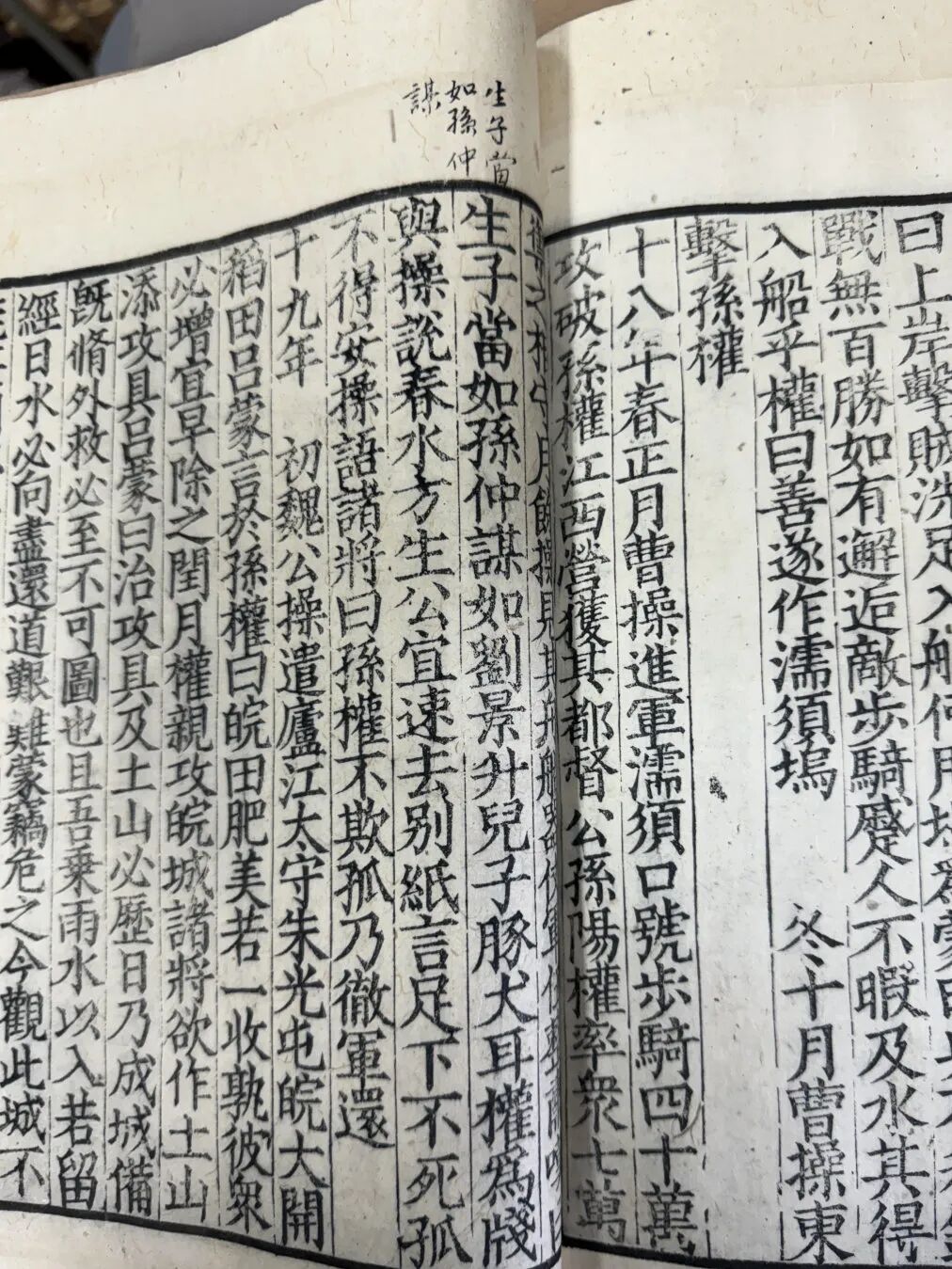

When Tang Bohu was reading *Zizhi Tongjian* (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government), he liked to directly copy out passages from the original text when encountering important historical moments. His attention also shifted interestingly when reading about the fascinating history of the Three Kingdoms period, and his annotations became more vivid!

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

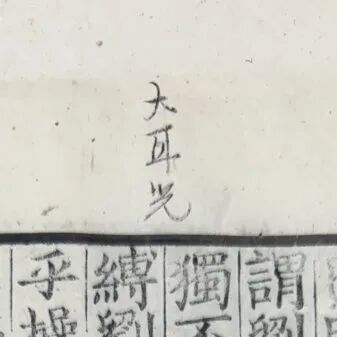

The phrase "大耳儿 (traditional Chinese character)" in the "Tongjian Jishi Benmo" was almost misread as "大耳光" (big slap).

When reading about Cao Cao usurping the Han throne, Lü Bu, known as "Lü Bu among men, Red Hare among horses," was captured by Cao Cao and hoped Liu Bei would plead for his life. However, Liu Bei instead reminded the suspicious Cao Cao. Before his death, Lü Bu angrily rebuked, "Big-eared rascal, you're the most untrustworthy!" Liu Bei was born with large ears, and Tang Bohu wrote the annotation "Big-eared rascal," as if he also found the nickname quite amusing.

Even more interestingly, Tang Bohu also discovered a famous quote from Cao Cao in the book: "A son should be like Sun Zhongmou (Sun Quan)." The second half of the quote, which Tang Bohu didn't remember, is: "Like Liu Biao's son, he's nothing but a pig or a dog." This means that one should have a son like Sun Quan, while Liu Biao's son is nothing more than a pig or a dog. During the Three Kingdoms period, Sun Quan led 70,000 soldiers to resist Cao Cao's army, and the two sides were locked in a stalemate for over a month. Cao Cao, seeing Sun Quan's well-organized and disciplined ships, weapons, and troops, uttered this exclamation.

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

These annotations reveal Tang Bohu's state of mind when reading; he wasn't just rigidly pursuing scholarship, but rather enjoying the pleasure of reading. When he encountered interesting historical materials, he would, like a modern person encountering a funny meme, secretly "memorize" the joke.

You should vent when you're angry.

"By studying history, we can understand the rise and fall of dynasties." Tang Bohu's approach to history was characterized by seriousness and earnestness.

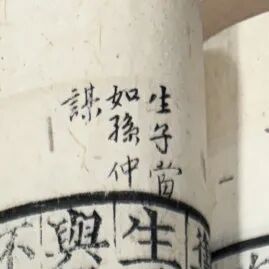

When reading about the "Wu-Wei Disaster" of the Tang Dynasty, especially the part about Wu Zetian's "regency," and how Pei Yan was framed and killed for requesting Wu Zetian to return power to the emperor, Tang Bohu's marginal notes became hurried and forceful. He angrily wrote, "Reading this, I regret not being an assassin to plunge a blade into the chests of Qian Weidao and Li Jingchen." Pei Yan was the de facto prime minister at the time, speaking frankly about his "duties," yet he was falsely accused of treason by Qian Weidao and Li Jingchen and executed.

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

Why was Tang Bohu so excited? This has to do with his own experiences.

In 1498, at the age of 28, Tang Bohu participated in the provincial examination in Nanjing and achieved first place, becoming an instant sensation. The following year, full of confidence, Tang Bohu went to the capital to participate in the metropolitan examination, but was implicated in a corruption scandal and imprisoned. He was ultimately dismissed from his official post and permanently lost his eligibility to enter officialdom through the imperial examinations. It was precisely because of this that he lamented Pei Yan's fate and felt indignant at the rise of petty officials.

Undoubtedly, the examination scandal was a fatal blow to Tang Bohu. He not only lost the coveted opportunity for an official career but also suffered criticism due to the stigma of "cheating." After returning to his hometown, he spent his days drinking and composing poetry. Later, he built Peach Blossom Hermitage as his residence, where he fully utilized his talents and devoted more energy to poetry and painting, becoming a renowned painter of his generation.

Record when you're drunk

The most interesting annotation appears at the end of Volume 21 of the *Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo*: "Tang Yin of Jinchang read it while drunk, starting from the section on the war between the North and South." Imagine Tang Bohu in the Dream Ink Pavilion of Peach Blossom Hermitage, drinking wine and reading. When he got excited, he picked up his brush and wrote on paper, his brushstrokes unrestrained and free, and he even recorded that he started reading from the section on the war between the North and South.

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

Tang Bohu's ancestor was Tang Hui, the General of Lingjiang in Jinchang County, Liangzhou, during the Former Liang Dynasty. Although his family had moved to Suzhou as early as the beginning of the Ming Dynasty, he still regarded Jinchang as his ancestral home and often signed his calligraphy and paintings "Tang Yin of Jinchang." This was a form of cultural identification and a way of tracing his family history. According to Zhu Yunming's "Record of the Dream Ink Pavilion," Tang Bohu once visited Jiuli Lake and stayed overnight at Jiuxian Temple. In his dream, an immortal bestowed upon him ten thousand ink sticks, which is why he named the pavilion in Peach Blossom Hermitage "Dream Ink Pavilion."

"Peach Blossom Village" by Chen Chun (Ming Dynasty), Palace Museum

In the hazy, drunken world of Tang Bohu, history and reality intertwine, and individual destinies rise and fall in the river of history—this is the true meaning of "drunken reading."

The "Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government" exhibited this time bears not only Tang Bohu's collector's seals "Nanjing Jieyuan" and "Tang Yin's Private Seal," but also Pan Zuyin's seals such as "Pan Zuyin's Collection of Books" and "Pan Boyin of Wu County's Lifetime Appreciation," indicating that the book was later collected by "Azu" into his book box.

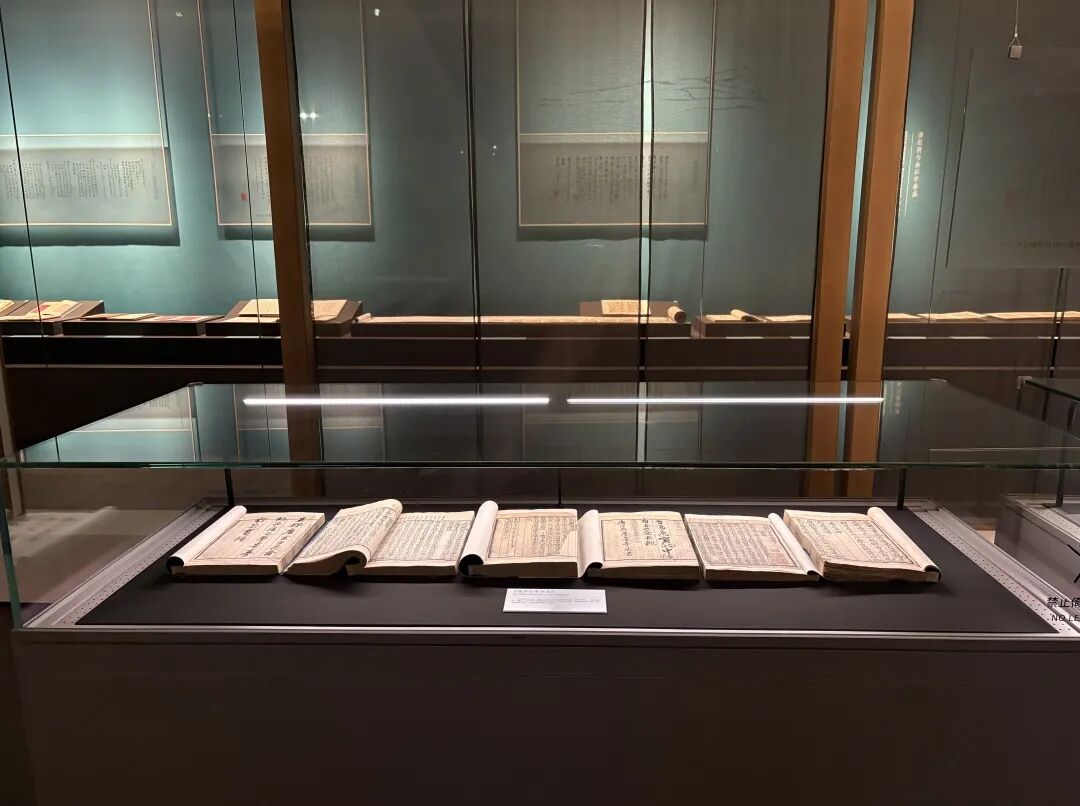

Exhibition site

Exhibition site

Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo

Leaving aside the many labels attached to Tang Bohu, we can see his most authentic state when reading from his handwritten annotations of "Zizhi Tongjian Jishi Benmo": sometimes smiling knowingly, sometimes slamming his fist on the table, sometimes writing in a drunken stupor. This also allows us to see a more three-dimensional and authentic picture of a scholar's daily life.

(This article is based on content from the Shanghai Library's official WeChat account.)