The Paper learned that a symposium on "The History and Culture of the Silk Road and the Prominent Characteristics of Chinese Civilization" was recently held in Beijing. More than 70 scholars from universities and research institutions such as the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Renmin University of China, and the Chinese Academy of Arts participated and shared their insights on the topic. The symposium included four parallel forums on the themes of "Documents, Objects, and Insights," "Techniques, Folklore, and Trade," "Utensils, Images, and Decorations," and "Sound, Music, and Symbols." The participating scholars discussed the history and culture of the Silk Road and the prominent characteristics of Chinese civilization, jointly painting a clear, three-dimensional, and vivid historical picture of the Silk Road.

"Although geographically distant, their cultures and aesthetic values closely connect them."

The study of decorative patterns is a crucial bridge in archaeology, connecting form with meaning and object with human perception. It has long transcended the simple category of "artistic decoration," becoming one of the core methods for interpreting ancient society, thought, and technology. Huang Jinqian of the School of Language Sciences and Arts at Jiangsu Normal University, in his paper titled "Ancient Road, West Wind, Galloping Horse—The Golden Galloping Horse Unearthed at Kulansarik and Its Reflection of Early Chinese Cultural Exchange," compared the decorative patterns on the golden galloping horse unearthed from the Kulansarik tomb in Xinjiang during the Warring States period with those on the golden horse relief from the Xinzhuangtou cemetery in Yi County, Hebei Province, concluding that "the two share a high degree of similarity in their artistic style."

In his report, Huang Jinqian stated, "Although they are from similar periods but geographically distant, this similarity must be related, indicating that the underlying cultural and aesthetic concepts are consistent." Furthermore, he analyzed the cross-cultural transmission path of the eagle-deer motif, arguing that it entered the Central Plains via the Western Regions and the Hexi Corridor, with clear evidence dating back to the mid-to-late Western Zhou Dynasty. Huang Jinqian specifically pointed out that the white-lipped deer image in the motif "refreshed our understanding of the distribution of early wild animals," reflecting the interaction between climate, species, and the human environment at that time. His research, starting from microscopic artifacts, macroscopically reveals that "from prehistoric times to the Warring States period, continuous cultural and ethnic exchanges existed before the opening of the Silk Road."

The "Golden Eagle Pecking a Deer" unearthed from the Kulansarik Tomb in Akqi County

The dissemination, imitation, and variation of images provide excellent evidence for studying cultural interactions, trade routes, and even ethnic migrations between different regions. Many of the articles presented focused on image research. Associate Professor Li Hailei of the School of Public Art at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, in his paper "The Compilation and Research of Pictorial Historical Materials on the Ethnic Integration of the Ancient Silk Road—Taking Sogdian Merchant Images as an Example," proposed a research path of "image-based historical verification and mutual verification between images and history," drawing on years of fieldwork. He argued that the Silk Road was a "cross-border system of cross-regional flow, cross-media intersection, and cross-ethnic integration," and that the collision of heterogeneous cultures was precisely the source of the innovation of Chinese civilization.

Through analysis of images such as the "Merchant Encounters Thieves" mural in Mogao Grottoes and the stone carvings on the stone bed in the Anjia Tomb, he interpreted the role of Sogdian caravans in Silk Road trade: "They were not only merchants, but also cultural envoys, spreading the culture of the Central Plains and Central Asia in both directions." Li Hailei emphasized that the scenes in the images, such as caravans praying, camels healing, and encountering thieves while crossing mountains, are both visualizations of Buddhist stories and reflections of real trade activities.

A partial view of the stone screen bed in the Anjia Tomb, which was decorated with gilding.

Liu Ning of the Zhengzhou Art Museum also focused on the theme of "foreign merchants." Taking the image of "foreign merchants leading camels" from the "Pottery Well Brick" collection of the Zhengzhou Art Museum as a starting point, she explored the value of Han Dynasty stone reliefs in the cultural integration of the Silk Road. She sorted out the motifs such as the war between the Han and foreign peoples, camels, elephants, and auspicious dragons, pointing out that these images are not only "a manifestation of the traditional concept of longevity and the eastward spread of Buddhism," but also "an early example of how the economic base promoted the commodification of culture."

Beyond the obvious "exotic" images and patterns, the cultural symbols, philosophical ideas, and spirit of the times behind many images need to be analyzed within the historical context in which they were created. Wang Gujin, a curator at the Art and Documentation Museum of the Chinese Academy of Arts, focuses on the mutual fighting motif and oxcart imagery on the lids of Boshan censers, arguing that they possess strong characteristics of foreign cultures. Wang Gujin explains that while the shape of the Boshan censer is related to the use of incense, its decorative images, such as "humans and beasts facing each other, oxcarts, etc.," may have originated from northern grasslands or Persian culture. He further suggests that the design of the Boshan censer lid may have imitated the Shanglin Garden during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han, reflecting the concept of "miniature world," satisfying the emperor's "vanity of conquering the world" while also reflecting "the absorption and reconstruction of foreign cultures." These images subsequently became stylized, becoming "popular patterns," and their early unique meaning gradually diminished during dissemination.

Boshan censer unearthed from the Han Dynasty tombs in Mancheng

Grotto art as a "complete time capsule"

Grotto art is a "complete time capsule." Today, grotto art research has evolved from simply appreciating art and viewing objects of religious worship into an interdisciplinary field that comprehensively utilizes multidisciplinary methods to interpret ancient civilization exchanges, social beliefs, technological crafts, and artistic thought. The scholars at the conference believed that the depth and breadth of grotto art research directly reflects our ability to understand the ancient world.

In her report, "The History of Multi-Lines: The Generation of Chinese Art Discourse from the Perspective of Dunhuang Folk Art and Buddhist Statues," Lü Zijing, a lecturer in the Department of Art Education and Art History at Hebei Academy of Fine Arts, criticized the Western-dominated writing of Chinese art history, pointing out that it simplifies Chinese art into "a dialogue with literati painting as the main theme." She advocated for a paradigm shift in research, moving "from author to field, from style to concept, from image to materiality." In her lecture, she used examples such as Dunhuang art, the localization of Buddhist statues, and folk paper horses to illustrate the diversity of Chinese visual culture.

Lü Zijing believes that a more inclusive discourse system for Chinese art should be constructed. For example, traditional art focuses on the style and life of individual painters. "However, it may be more important to study the overall artistic field of the cave, including its space, function, patrons, and donors, rather than focusing on verifying which painter created a particular mural."

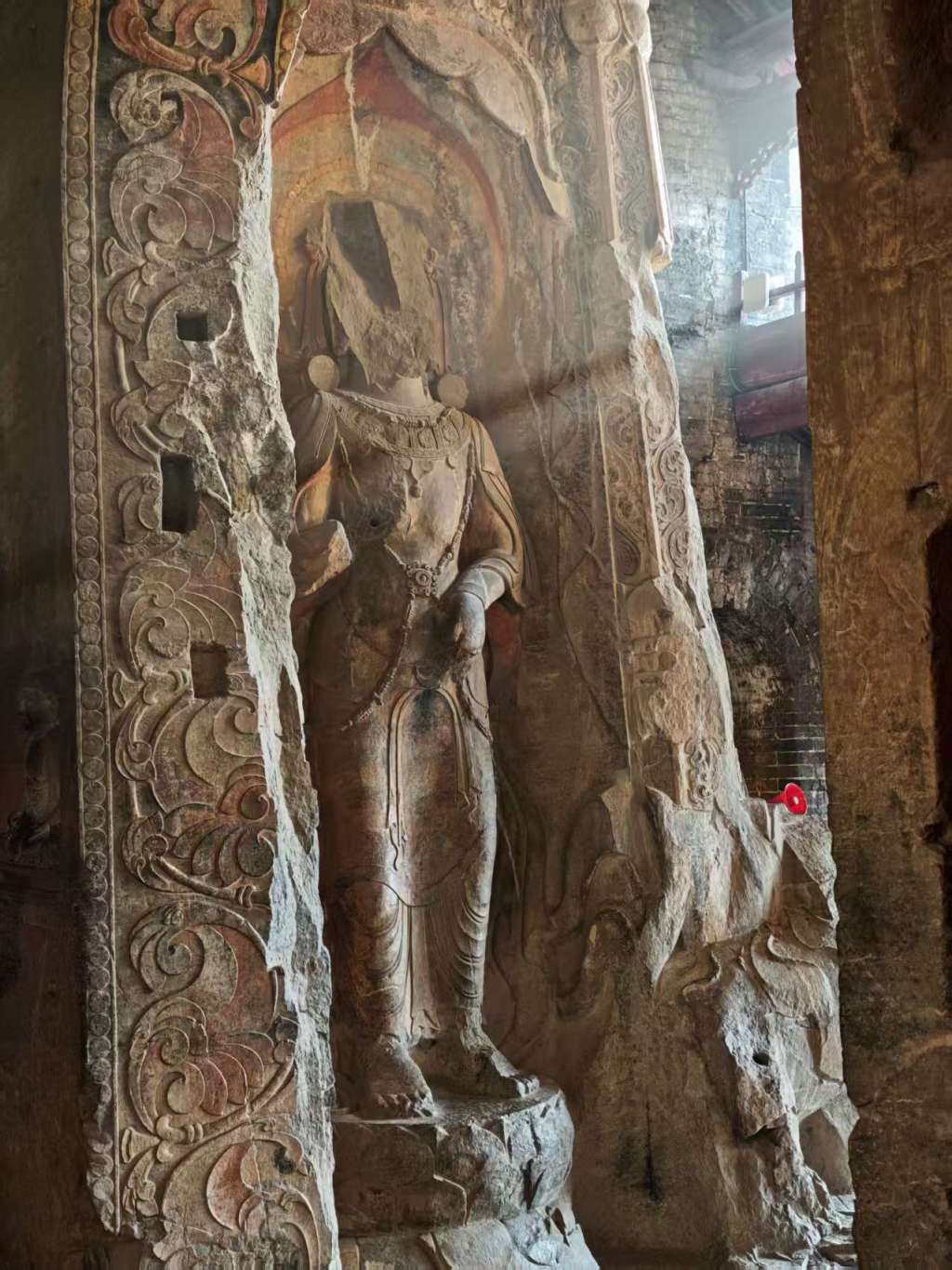

Xiangtangshan Grottoes

The grotto remains provide researchers with a continuous source of research material. In her paper, "The Dance of Civilizational Exchange: A Study of the Reverse-Playing Pipa Images in Dunhuang during the Tubo Period," Xu Qiannan, a master's student at Wuhan Sports University, analyzes images of the reverse-playing pipa in Mogao Grottoes Caves 112 and 158, pointing out the transformation from "male Hu musicians" to "female celestial musicians," reflecting Dunhuang's transformation into a "cultural melting pot" during the Tubo period. She argues that this dance posture possesses both "the physiological basis of real dance" and "the philosophical meaning of 'reversal is the movement of the Tao,'" representing "a perfect combination of religious sacredness and secular life."

The "Reverse-Playing Pipa" in Mogao Grottoes Cave 112

Wang Bohao, a master's student at Xinjiang Arts University, analyzed the multicultural characteristics of the clothing of the King and Queen of Kucha in Cave 205 of the Kizil Grottoes. He pointed out that the King's brocade robe, gold belt, and narrow sleeves and trousers "blended the styles of Persian and northern nomadic peoples," while the Queen's crown and waist-cinching long skirt reflected "a combination of aesthetics and practicality of the plateau peoples." Through 3D reconstruction and dynamic images, Wang Bohao visually presented the shapes and colors of Kucha clothing, emphasizing that it "was not only a tool for keeping warm and covering the body, but also a symbol of social customs and religious beliefs."