In Buddhist art, the unique allure of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva lies in his earth-shaking vow: "I will not attain Buddhahood until hell is empty." Whether it's the Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva statues of Dunhuang art or the Northern Song Dynasty Ksitigarbha statue of Mount Jiuhua covered with a hat, housed in the Freer Gallery of Art, most depict scenes with striking visual impact, leaving a lasting impression.

There is actually a very simple interpretation of Ksitigarbha:

Di (di) means the mind; Zang (zang) means treasure. Ksitigarbha (di zang) refers to the treasure of the mind. Every living being possesses boundless wisdom, virtue, and talent; this is the original meaning of Ksitigarbha. The Mani Pearl in the hand of the Dunhuang Ksitigarbha statue represents the treasure of the mind.

I have a bright pearl, long locked up by dust and dirt. Now the dust is gone and the light is born, illuminating the thousand green hills.

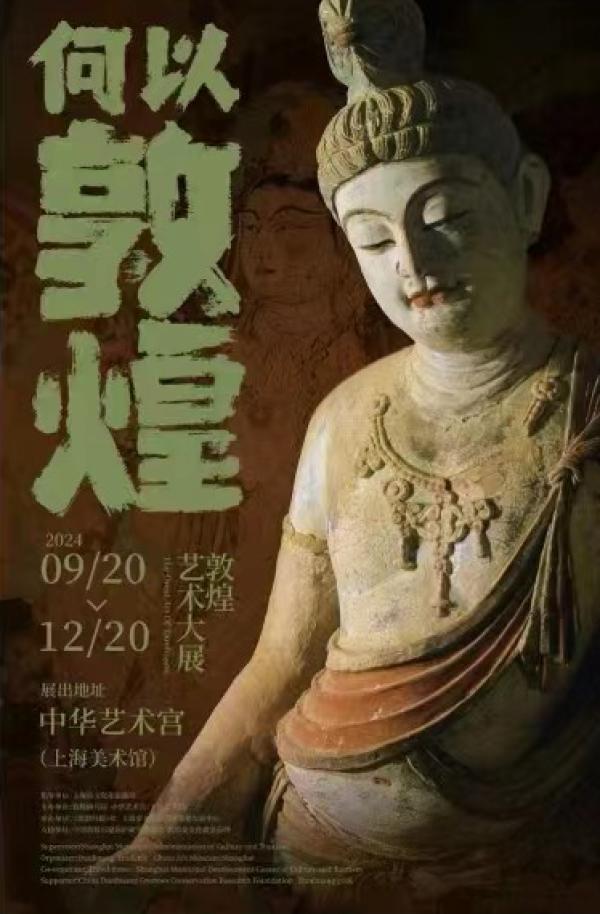

Silk painting of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva from the Dunhuang Caves

The Dunhuang illustrated edition of the "Buddha Speaks of the Ten Kings Sutra" contains eight copies (combined into five), while the Dunhuang text of the "Buddha Speaks of the King Yama's Precepts for the Four Groups of People to Practice the Seven Fasts and Merit to Rebirth in the Pure Land Sutra" contains 46 copies, which after compilation has become 37. Both texts involve the belief in Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and the Ten Kings.

Unearthed from the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, Stein's Dunhuang silk painting, late Tang Dynasty, "The Six Paths of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva", now in the collection of the British Museum

In the early Tang Dynasty, Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva often held a jewel and made hand seals. Later, a capped Ksitigarbha appeared, holding a jewel and a staff. A Northern Song Dynasty silk painting of a capped Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, unearthed from Kiln 17 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, measures less than one square meter (76 x 59 cm), yet vividly depicts the scene of offerings to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva. The main Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva sits gracefully on a rock, adorned with a halo and a body halo. His black cap is stylish, and his robes are exquisite. Light bands on either side of his halo represent the six realms of beings: human beings wear crowns, celestial beings wear flowing robes, animals are running, asuras are about to fight, and hell beings are suffering. Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva's left hand holds a Mani pearl with a flame pattern, his right hand holds a staff, and his left foot rests on a red lotus. The good and evil boys on his left and right wear Han Chinese clothing and headdresses, blue and green robes, respectively, and hold scrolls.

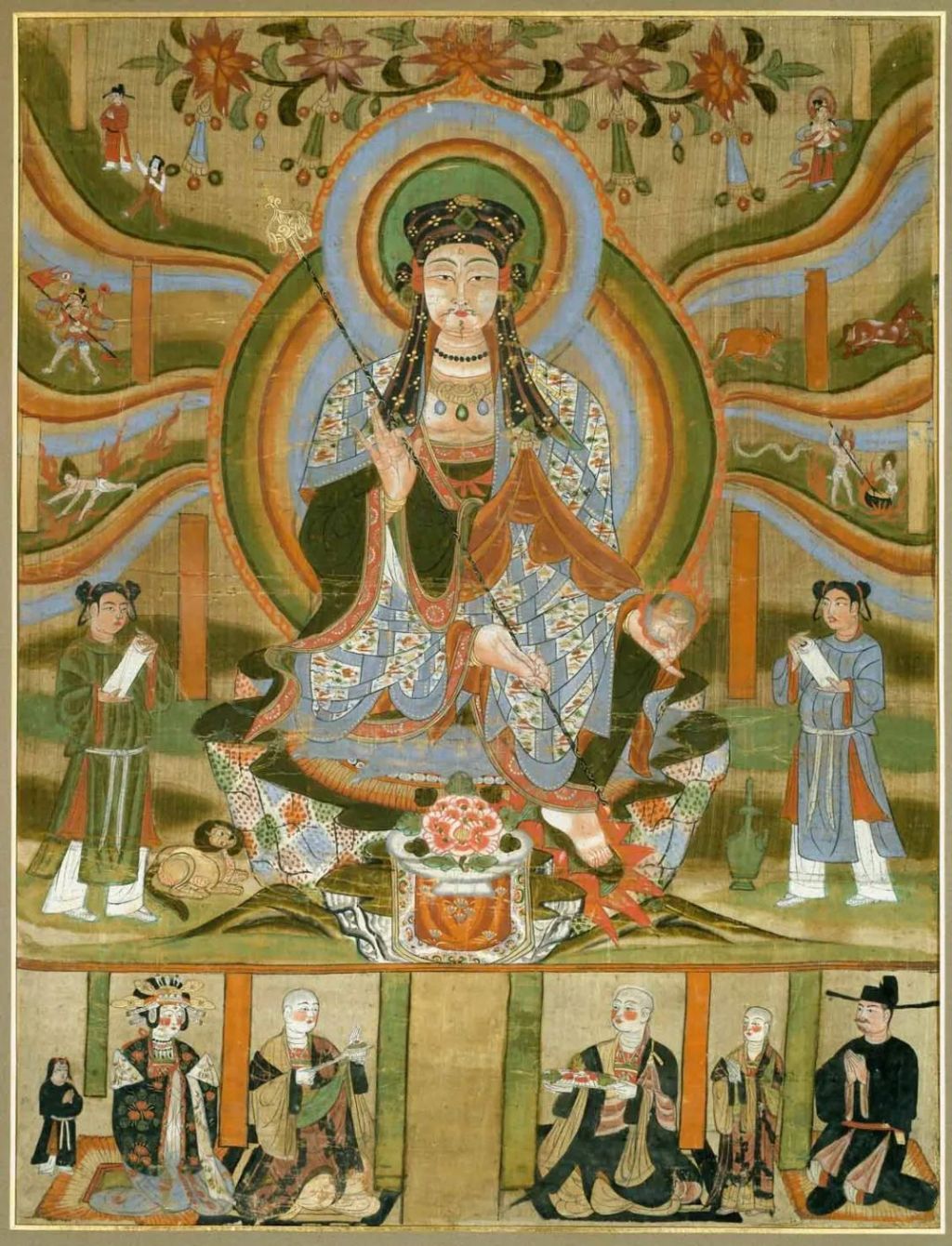

The Northern Song Dynasty Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva is collected by the Guimet National Museum of Asian Arts in France

The Dunhuang silk painting of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva in the Guimet National Museum of Asian Art in France shows peonies blooming on the altar, and the divine beast Di Ting is curled up obediently on the ground. There are three monks below, two of whom are holding offerings. The male and female donors are bowing respectfully. The female donor is kneeling with her sleeves rolled up, wearing gorgeous clothes and gorgeous hair accessories. The male donor is wearing official uniform and a black cap, kneeling on the carpet with his hands folded. The girl behind the female donor also has her hands folded.

The Five Dynasties period, "Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings and the Pure Land", collected by the Guimet Museum of Asian Art, France

In relieving suffering and relieving distress, all bodhisattvas embody the Buddhist principle of compassion. The concept of the six realms of reincarnation was once deeply ingrained in people's minds, and Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva made a grand appearance in six different forms, traveling to and from different realms, each with its own distinct imagery. Thus, there are the Danta Ksitigarbha, the Jewel Ksitigarbha, the Treasure Seal Ksitigarbha, the Earth-Holding Ksitigarbha, the Obstacle-Removing Ksitigarbha, and the Sunlight Ksitigarbha. Sutra paintings aim to educate, and the images of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, the classic stories, and the visually striking scenes are unforgettable.

The Northern Song Dynasty Jiuhuashan Ksitigarbha statue, housed in the Freer Gallery of Art in the United States, is exceptionally vibrant and vibrant, a rare find among Dunhuang paintings. This painting is particularly renowned among Dunhuang's remaining paintings, as it was one of the first Dunhuang silk paintings to escape from the Mogao Caves' Scripture Caves. In 1902, when Taoist Wang selected these paintings from the Scripture Caves and walked 50 miles to visit the Dunhuang County Magistrate and his successor, Wang Zonghan, he had no idea that the painting would end up in Japan and New York. Despite enduring such turbulent times, crossing oceans, and making numerous journeys, it has remained remarkably well-preserved.

The first batch of silk paintings of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva from Dunhuang that were exiled from Northern Song Dynasty are now in the collection of the Freer Gallery of Art.

The main Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva sits sideways in a semi-lotus position, one leg bare, the other in flip-flops, and wearing a cap adorned with a stylish plum blossom. In his left hand, he holds a Mani jewel, while his right appears to point at a nearby monk. The monk kneels on the ground, his hands in a mudra, his face full of compassion. Above him is the inscription "Monk Daoming." The golden-haired lion, with its clean, fur-lined fur, looks adorable and smiling.

The inscription "Namo Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" appears in the upper right corner of this Dunhuang silk painting, followed by the inscription "Painted and donated on the anniversary of the deceased's death," indicating that the painting was done to offer blessings and salvation for the deceased. From the Tang Dynasty to the Five Dynasties, influenced by Buddhist concepts of reincarnation, the "Five Path Gods" became widespread in folk belief. These were the Five Path Generals, deities of the underworld. These Five Path Generals, similar in function to the ancient Chinese Lord of Mount Tai and the Buddhist King Yama, oversee matters related to hell and the demonic realms. On the lower right side, a female donor in rich attire kneels on a red carpet, holding flowers in one hand and incense in the other. Two young girls follow, and the inscription reads, "Offerings from the late Princess Li of the Golden and Jade Kingdom of Khotan." This painting depicts Princess Shengtian, the third daughter of King Li Shengtian of Khotan, who married Cao Yanlu, the governor of the Guiyi Army. She had already died at this time, and this painting was done on the anniversary of her death. Ksitigarbha cults place particular emphasis on cultivating the merits and wisdom of family members for their ancestors.

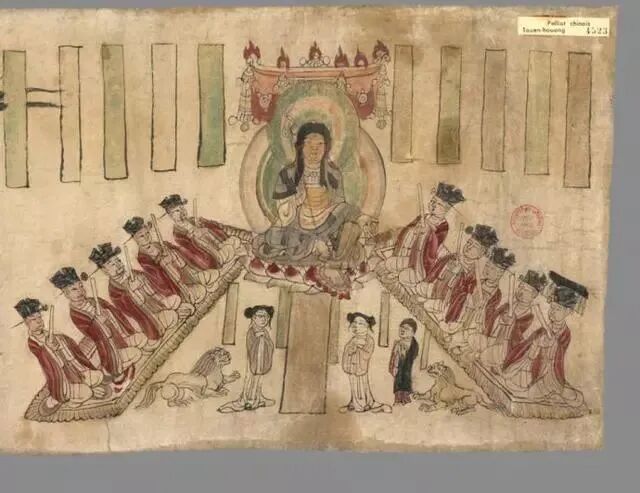

Unearthed from Cave 17 of the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, and collected by the Guimet Museum in Paris, France, is a Northern Song Dynasty silk painting by Pelliot titled "Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and the Ten Kings."

Chinese culture is a culture of seeking the truth. Respecting the truth and valuing virtue, pursuing truth and embracing enlightenment are the core values of this culture . Therefore, alongside the worship of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, Monk Daoming and Duke Min often accompany them. The remarkable connection between Duke Min and Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva began during the Tang Dynasty. The Silla monk Jin Gyo-gak, an incarnation of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, visited China. At the time, the landowner Duke Min was hosting a feast for monks on Mount Jiuhua, and Jin Gyo-gak joined the feast, making up the total number of 100. After the feast, Jin Gyo-gak asked Duke Min for a piece of his robe to cultivate, and the Duke generously agreed. Jin Gyo-gak threw his robe into the air, and it covered nine peaks. Deeply enlightened by the nature of emptiness, Duke Min graciously donated the entire Mount Jiuhua, becoming the Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva's monastery in Chizhou, Anhui. Duke Min also allowed his only son to become a monk under Jin Gyo-gak—this became Monk Daoming. On both sides of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva are two attendants. The one standing on the right is dressed in secular clothes, namely Min Gong; the one standing on the left is dressed in monk 's clothes, which is Monk Daoming. This shows the idea of conscious repayment of gratitude and respect for the Dharma and monks in Chinese culture.

In any circumstances, he never loses his inner purity and clarity, never abandoning sentient beings. Moreover, he enables all sentient beings to eliminate afflictions and incorrect perceptions, allowing them to dwell in a pure inner environment. This is the perfect interpretation of the Mani Pearl in Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva's hands: a pure mind, free from afflictions.

In the sutra painting, the good and evil children beside Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva and the scrolls they hold in their hands are depicted. Ten kinds of good and evil, expressed through the three channels of body, speech, and mind, are recorded in these scrolls, depicting a lifetime. At the time of death, judgment is based on karma. Everyone's life, whether a masterpiece or a remnant, is essentially a self-inflicted fate. Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, ever mindful of sentient beings, frequently journeys in and out of various hells, saving those in the ghost realm. His boundless compassion earns him the title of Lord of the Netherworld. This is the core theme of the Dunhuang Ksitigarbha Sutra painting, reminding us to revere and manage the consequences of karma.

The Five Dynasties period, "Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings and the Pure Land", collected by the Guimet Museum of Asian Art, France

The "Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings and the Pure Land" painting, collected by the Musée National d'Arts Asiatique Guimet in France, is a Five Dynasties period silk painting unearthed in Dunhuang. The composition is divided into two parts: the Pure Land image on the upper part and the Ksitigarbha and the Ten Kings image on the lower part. The upper Pure Land image, with its terrace overlooking the pond, represents the Pure Land of Amitabha. The principal figure is Amitabha Buddha of the Western Paradise, preaching. Flanked by Bodhisattvas are Avalokitesvara and Mahasthamaprapta. Treasures emanate from the Seven Treasures Pond, and the Eight Meritorious Waters shimmer. The Bodhisattvas of the Musical Instruments perform a musical instrument. Behind, on both sides, the Heavenly Kings and monks gaze intently at Amitabha Buddha. Clearly, it is class time in the Pure Land of Ultimate Bliss.

In the lower Ten Kings painting, Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva wears a hood and robes, his left hand holding a crystal-like Mani Pearl. One leg is folded, the other resting on a red lotus, as he sits on a blue lotus throne. Six colorful clouds emanate from his head and backlight, within which reside sentient beings from the six realms, including celestial beings riding on the clouds. In the foreground, Monk Daoming stands facing a golden-haired lion. The Ten Kings, dressed in Hanfu and crowns, hold white scepters. A title flanking each of them highlights the core of this sutra painting: the "Sutra of the Ten Kings."

Dunhuang Buddhist Paintings of the Ten Kings Sutra

Many themes of the Ksitigarbha Sutra paintings in Dunhuang come from the "Ten Kings Sutra", and the core content involves the judgment of the Ten Kings (Buddhas and Bodhisattvas) after death.

The National Library of France collects Pelliot's Dunhuang painted scroll: The Ten Kings of Hell Sutra

The National Library of France collects the Pelliot Dunhuang manuscript of the Sutra of the Ten Kings

In the process of visualizing Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, his earth-shaking vow is his unique charm: he will not attain Buddhahood until hell is empty. For eternity, he will continuously save and liberate all sentient beings, like a mother to them, and transform hell into a pure land.

Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva of the Kamakura period at the Nara National Museum, Japan

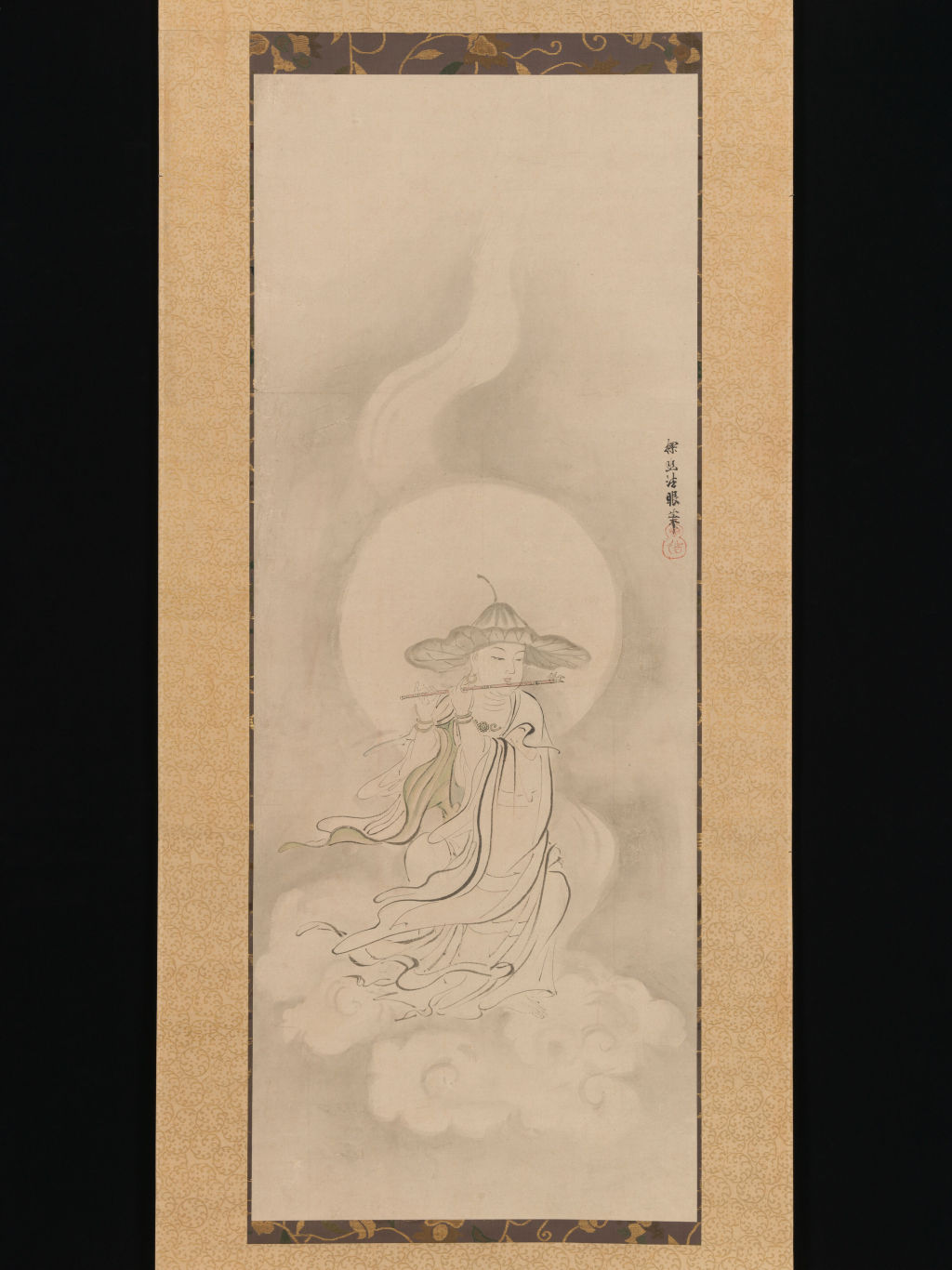

Japanese Kano explores the mystical world of Ksitigarbha through flute playing

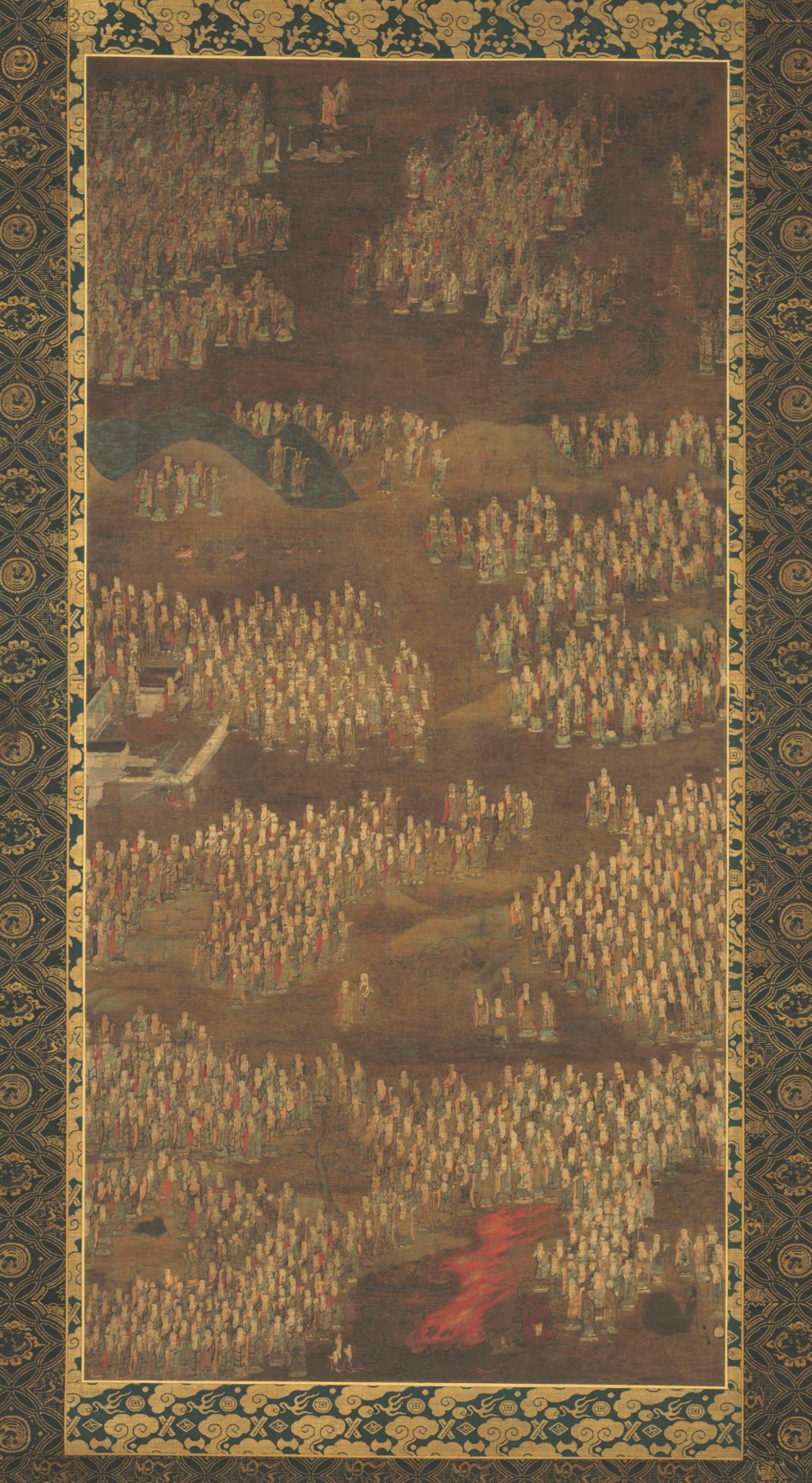

Japanese Anonymous Japanese Kasuga Thousand-body Ksitigarbha Picture

Japan still has the "Thousand-bodied Jizo" (a bodhisattva). The "thousand" represents vastness, filling hundreds of thousands of Ganges-sand worlds. In each world, he manifests hundreds of thousands of millions of bodies, each of which saves hundreds of thousands of millions of people. This is endless, just like the Thousand-armed Avalokitesvara and the Thousand-bowl Manjushri. It represents the essence and function of the bodhisattva—the essence and wonderful function of the mind.