During the Autumnal Equinox, a cool breeze begins to arrive. The ancients called the eighth month of the lunar calendar "Mid-Autumn." During these two days, the weather in southern China has changed from scorching heat to cooler temperatures.

The Autumnal Equinox falls midway through the ninety days of autumn, dividing the autumn season equally. Autumn carries a melancholy of longing, like the yearning for water shield and sea bass. There's a story from Shishuo Xinyu: "Zhang Jiying, appointed an official in the Eastern Division of the King of Qi, was in Luoyang. Seeing the autumn wind rising, he longed for the water shield soup and sea bass sashimi of Wu." Water shield and sea bass are delicious, but my craving is for water chestnuts.

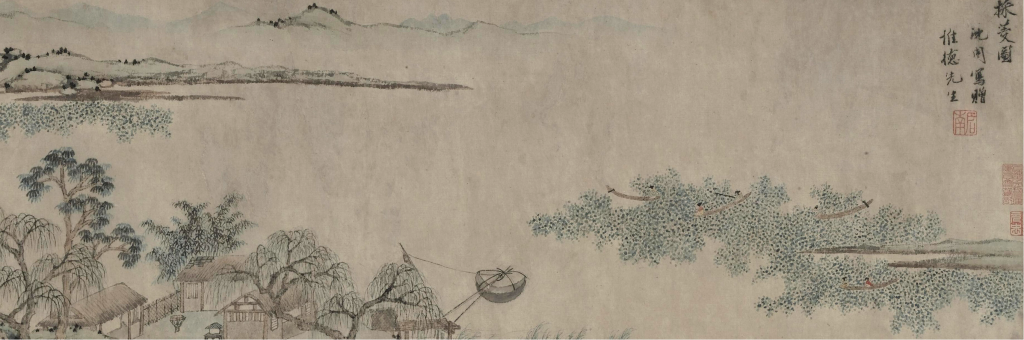

"Imitation of Qiu Shifu's Painting of Picking Water Chestnuts" by Wang Hui, Qing Dynasty, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Water chestnuts are a delicacy from the south of the Yangtze River. Ancient people also wrote water chestnuts as "芰实" (芰实), and in ancient times, the difference between "Ling" and "芰" was based on the number of their pointed corners.

Wang's Wuling Records states: "Two-cornered water chestnuts are called ling, while four-cornered and three-cornered ones are called ji. Their leaves resemble water chestnuts, and their fruits are white and red." Two-cornered ones are called ling, while three-cornered and four-cornered ones are called ji. Nowadays, the term "ji" is no longer used; they are all called ling. Wild water chestnuts were unearthed at the Luojiajiao site in Tongxiang. It's not that water chestnuts were smaller in ancient times. Rather, wild water chestnuts had not been artificially bred, resulting in small leaves and fruits, and sharp, rigid corners that could easily prick people. In times of famine, wild water chestnuts were also used as a food to alleviate famine. In the past, most people in water towns would raise domestic water chestnuts. Domestic water chestnuts have larger leaves and fruits than wild water chestnuts, and their corners are soft and crisp, ranging in color from green to red to purple. When young, they are shelled and eaten, with a thin skin and crispy flesh. As they mature, their shells harden and turn black, sinking to the bottom of the river. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, they were called "black water chestnuts." Water chestnuts are mostly planted in March. Transplanting water chestnut seedlings around the Qingming Festival and the Beginning of Summer—this isn't difficult. Simply wrap the sprouted water chestnuts in mud and drop them into the pond. The seeds will settle into the mud, making them most resilient. Because water chestnuts tolerate deep water and float with the currents, they are much more resilient than lotus and water caltrops. Ruan Yuan, a Qing Dynasty poet, summarized Huzhou's farming practices in his "Miscellaneous Poems of Wuxing": "Plant water chestnuts in deep water, rice in shallow water, and lotus in neither deep nor shallow water." If left unchecked, water chestnut seedlings can roam freely, obstructing waterways and making harvesting difficult. Therefore, bamboo poles tied with straw ropes are used to mark the boundaries of lakes and rivers. From ancient wild life to cultivated cultivation, water chestnuts later also found their way to the estates of literati, such as Wu Kuan's Dongzhuang.

The painting of Dongzhuang by Shen Zhou in the Ming Dynasty, Nanjing Museum, shows Linghao.

Dongzhuang, a renowned literati garden in Suzhou during the Ming Dynasty, was founded by Wu Kuan's father, Wu Mengrong, and further developed by three generations of the Wu family. Liu Daxia's poem "Dongzhuang" says, "Wu's gardens rival those of Luoyang, yet only Dongzhuang stands tall after a century." Suzhou gardens were already renowned at the time, and the Wu family's Dongzhuang was a prime example. Located inside Fengmen, it was originally the site of Qian Wenfeng's "Dongshu" (East Villa) of the Wuyue Kingdom during the Five Dynasties. It was abandoned as farmland during the Yuan Dynasty and rebuilt in the Ming Dynasty, becoming a cultural landmark east of Suzhou. The garden's waterscape is particularly prominent, and Linghao (Linghao), a waterway dedicated to water chestnut cultivation, is one of Dongzhuang's Eighteen Scenic Spots. In the tenth year of the Chenghua reign, the painter Shen Zhou visited Wu Kuan's father, Rong, at Dongzhuang. His "Dongzhuang Album" depicts the Wu family manor.

Wu Kuan, courtesy name Yuanbo and pseudonym Pao'an, was known as Mr. Pao'an. He placed first in both the Imperial Examination and the Imperial Court Examination in the eighth year of the Chenghua reign of the Ming Dynasty. Wu Kuan had a close relationship with Shen Zhou and was also a teacher of Wen Zhengming. In his "Yutang Conghua" (Yutang Conghua) by Jiao Hong, it is written: "Wu Wending was fond of ancient mechanics and never tired of studying them until old age. He shunned power and fame as if in fear. While a Hanlin scholar, he cultivated a garden and pavilion to the east of his residence, planted flowers and trees, and after court, he would hold a scroll, reciting it daily. On auspicious occasions, he would invite guests and entertain them with couplets on assigned topics, seemingly unaware of their official duties." Dongzhuang is renowned for its waterscapes. Li Dongyang recorded in his "Dongzhuang Ji" that "Linghao converges in the east, Xixi runs along the west, and both harbors are accessible by boat." As a key water system within the garden, Linghao is both a scenic element and a symbol of the integration of farming and literati life. The scenery of Linghao was described many times in Ming Dynasty poems. Wu Kuan's own poem "On the Rain" uses the line "Looking east at Linghao, it's nice to go home, Wu Nong's family has magnolia oars" to describe the fun of boating on Linghao in Dongzhuang in the rain; Wang Bi's "Linghao in Dongzhuang, Wu Shaozai" depicts the scene of picking water chestnuts: "Whose magnolia boat is it, picking water chestnuts on the moat. Singing at dusk, returning home, the sky is cold and the autumn water is falling." The poems of Wu Yan and Shi Bao focus on the details of picking water chestnuts, such as "The water chestnut heads first prick people, and the water chestnut leaves are already in disarray" and "Residents come to pick water chestnuts, and the water chestnuts gradually have thorns", showing the growth of water chestnuts and the interaction between people.

Reading the poems of Ming Dynasty poets makes one curious about what kind of water chestnuts were planted in the water chestnut fields at that time. Unfortunately, the famous Dongzhuang did not survive like the Humble Administrator's Garden and the Lion Grove. We can imagine the elegance of the water chestnut fields through the poems and paintings of literati.

A woman picking water chestnuts in a Qing Dynasty meticulous figure painting

Besides wild water chestnuts, China also boasts a wealth of exceptional varieties. The Tang Dynasty's "Youyang Miscellaneous Records" mentions Suzhou's two-cornered "Zheyao" water chestnut and the triangular, awnless Yingcheng water chestnut. The Song Dynasty's "Xianchun Lin'an Chronicles" distinguishes between "Shajiao" water chestnuts and "Wonton" water chestnuts. The Jin Dynasty's "Food Materia Medica" provides even more detailed accounts. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, water chestnuts in Jiangsu and Zhejiang became more mature, with numerous varieties distinguished. At the time, water chestnut growth was closely tied to region. For example, Li Rihua, a Jiaxing native in the Ming Dynasty, recorded the "small green water chestnut" in his "Zipaoxuan Miscellaneous Records": "This species does not reach Weitang in the east, does not exceed Doumen in the west, does not reach halfway in the south, and does not reach Pingwang in the north. It covers an area within a hundred miles." Jiaxing's "small green water chestnut" is a hornless water chestnut, slightly smaller than the hornless Nanhu water chestnut. Another example is the Wanli Xiushui County Chronicles: "Among the aquatic fruits of Xiushui, there are three red varieties, namely the sand-cornered water chestnut and the rounded water chestnut; and two green varieties, namely the wonton water chestnut and the pointed-cornered water chestnut." Volume 11 of the Ming Dynasty Records of Superfluous Things by Wen Zhenheng of Suzhou records an even richer variety: water chestnuts are grown in the lakes and ponds of Wuzhong, as well as in private ponds. There are two types: green and red. The red ones are the earliest and are called "water red water chestnuts"; those that mature later and are larger are called "goose-coming red"; the green ones are called "oriole green"; the large green ones are called "wonton water chestnuts" and are the most delicious. The smallest ones are called "wild water chestnuts." There are also white sand-cornered water chestnuts, all of which are autumn delicacies, worthy of being recommended alongside lentils.

Nanhu Ling (Photo provided by the author)

Although water chestnut fields are becoming increasingly rare, the water chestnuts of Wuyue retain their ancient variety names and have their own admirers:

Water Red Water Chestnut: Two-horned, red and fresh, in season in May and June, best served as fruit when young. Wild Goose Red: Four-horned, large, red, ripening in August when geese arrive, hence the name. Sand Corner Water Chestnut: Domestically cultivated, the horns are smooth and soft. Wilderness has sharp, pricking horns. They are all green in color, in season around the time of Frost's Descent, and are best steamed and eaten when mature. Wonton Water Chestnut: A pictographic name. Two-horned, with some interspersed, large green in color, they are particularly delicious steamed. Wind Water Chestnut: Also known as Zheyao Water Chestnut, it is shaped like a bow, with two curved horns. Today, people shell and air-dry them when they are old, calling them water chestnut rice, and use them as fruit, often serving as gifts to guests. Black Water Chestnut: Similar in shape to the Zheyao Water Chestnut, it is slightly smaller and darker, like coal. The flesh, though white, has a bluish-black hue. At the end of winter, they are dug up from muddy soil; they have a strong, pungent smell and are delicious when cooked.

Picking Water Chestnuts (detail), with a small boat on the right side hidden in the lake. Ming Dynasty, Shen Zhou, Shanghai Museum

Cai Ling boat

The women picking water chestnuts in the fine-brush figure paintings of the Qing Dynasty use round buckets, which make it easier for them to move around between ponds.

Every year around the Autumnal Equinox, farmers, braving the rising sun and gentle breeze, invite their friends and family to the rivers and ponds to pick water chestnuts. This tradition has been practiced since ancient times. "A path blossoms among the water chestnuts, but at dawn, who will board the water chestnut-picking boat?" From ancient times to the present, picking water chestnuts and lotus flowers has become a poetic image of the south of the Yangtze River for people in the northwest. Shen Zhou's painting "Water Chestnut Picking" features a poem: "A woman from Linghu Lake sails in a small boat, her red makeup reflected in the clear water. How elegant is she? An emerald among flowers, a mandarin duck on brocade. Trying to turn over a green leaf, she mistakenly picks a purple horn, injuring her delicate fingers. Watching her depart, a loud song echoes through the setting sun." In reality, water chestnut picking is not as romantic and colorful as depicted by literati painters; it is extremely arduous labor. Pickers sit in a water chestnut bucket, paddling their way through the pond's floating green leaves. The water chestnuts hide underwater, so they must bend down to scoop up the entire hull before they can begin to pick them. Without experience, it's easy to fall into the river due to a loss of balance. There are labor songs on the rugged riverside, and water chestnut picking in the south of the Yangtze River. There are also water chestnut picking songs in Yuefu poetry, also known as water chestnut songs.

Song of Picking Water Chestnuts, Southern Liang Dynasty, Jiang Yan

In autumn, my heart is at peace, wading through the water to gaze at the green lotus. Purple water chestnuts can be picked, to ease the melancholy of the years. Beneath the jagged leaves of a thousand trees, ripples flow before a hundred streams. High and narrow valleys flow through, and fragrance fills the vast river. Songs echo the tunes of the oarswomen, dances echo the southern strings. Riding a turtle is not worldly; riding a carp is a way to aspire to the immortal realm. All beauty is believed to be so, and no regrets lie in the clear springs.

Boating women fill the center of the city, gathering water chestnuts without paying any attention to their horsemen. Amidst the shimmering water and hazy mist, they seek a glimmer of nature's sweetness. Since ancient times, literati have imbued the practice with rich and passionate imagination, their words brimming with poetic longing. But how can the imagery unfolded on paper match the vividness of real life? "Water Chestnut Pickers," by Fan Chengda of the Southern Song Dynasty, stands out from most poems on the subject:

The hardship of picking water chestnuts is like heavenly punishment, leaving your hands red and green. Don't ask about the song of Yang He crossing the river, just recite the Chu Ci for fun.

Women picking water chestnuts in paintings of the Qing Dynasty

The water chestnut-picking boats depicted in the painting vary in form: some resemble weaving shuttles, slender and graceful; others resemble barrels, simple and practical. The barrel shape facilitates maneuvering between ponds and embankments. When crossing large lakes and rivers, the long, shuttle-shaped boats can be loaded with water chestnuts and maneuver effortlessly. A line from a poem by Wang Wei reads, "Smoke and fire rise from the ferry, and water chestnut pickers are everywhere returning." It's like a painting depicting water chestnut pickers returning home at dusk, the fireworks bustling with the world, the swaying boats, a vivid yet tranquil scene.

Photo courtesy of the author

New water chestnuts arrive in the late seventh lunar month, but their peak season is around the Autumnal Equinox and Mid-Autumn Festival in August. Water chestnuts can be eaten raw as a fruit or cooked as a vegetable. Because they are high in starch, they are ground into flour for use in grain and pastries. At the end of autumn, the water chestnuts are harvested, and the remaining stems and leaves are used as pig feed. Picking is done every other week until the Double Ninth Festival. As the old saying goes, "Water chestnuts arrive in August, melons arrive in July, and water chestnuts arrive in September." Picking too early means the water chestnuts are not ripe, while picking too late means they sink into the water. The late Ming Dynasty gourmet Li Yu said that water chestnuts "are picked and eaten immediately, preserving their true beauty... waiting a little longer will diminish their color, aroma, and flavor." Even today, water chestnuts in Jiaxing are still soaked in cold water after being picked. "Soaking fresh water chestnuts in cold water makes the flesh even crisper." The key is freshness, and freshness comes in season. Water shield, water chestnuts, water caltrops, and lotus roots in this water town can all be used as both vegetables and fruits. Li Yu said: "When you peel crab, melon seeds and water chestnuts, you have to do the hard work yourself. If you peel them and eat them quickly, they will taste delicious. If someone else peels them and I eat them, it will not only taste like chewing wax."

Yuan Mei's "Suiyuan Food List" mentions "Braised Fresh Water Chestnuts," with the emphasis on "fresh": "Boil in chicken broth. When serving, remove half the broth. The ones that rise from the water are fresh, and the ones that float to the surface are tender. Adding fresh chestnuts or ginkgo nuts until soft is even better." The question is whether water chestnuts should be used as a vegetable or rice? As Wu Yan wrote in his Dongzhuang poem, "After picking water chestnuts, should we serve them as vegetables or rice?" For the people of Jiaxing, the choice is probably difficult. In the late Qing Dynasty, Xia Zeng praised the Wumen wonton water chestnuts, saying, "Cooked in a copper pot, the shells remain green and are exceptionally fragrant and glutinous." Even the hornless water chestnuts of my hometown require simple preparation: a little oil, a pinch of scallions, and a pinch of salt, stir-fry, then simmer with bacon and sausage to make water chestnut rice, a simple autumn delicacy.