The Record of Epigraphy and Inscriptions, written by the Song Dynasty scholarly couple Zhao Mingcheng and Li Qingzhao, is a leading work on epigraphy in ancient China. For centuries, the complete volume was generally believed lost until its rediscovery in the 1950s. How did this national treasure of a document make its way from private collection to rediscovery and ultimately to the public domain? The only extant complete Song-era edition, in all 30 volumes, is housed in the National Library of China. It has recently been republished in its original, full-size, high-definition color by Shanghai Painting and Calligraphy Publishing House.

Researcher Chen Hongyan, former director of the Ancient Books Library of the National Library, tells the story behind this legendary ancient book.

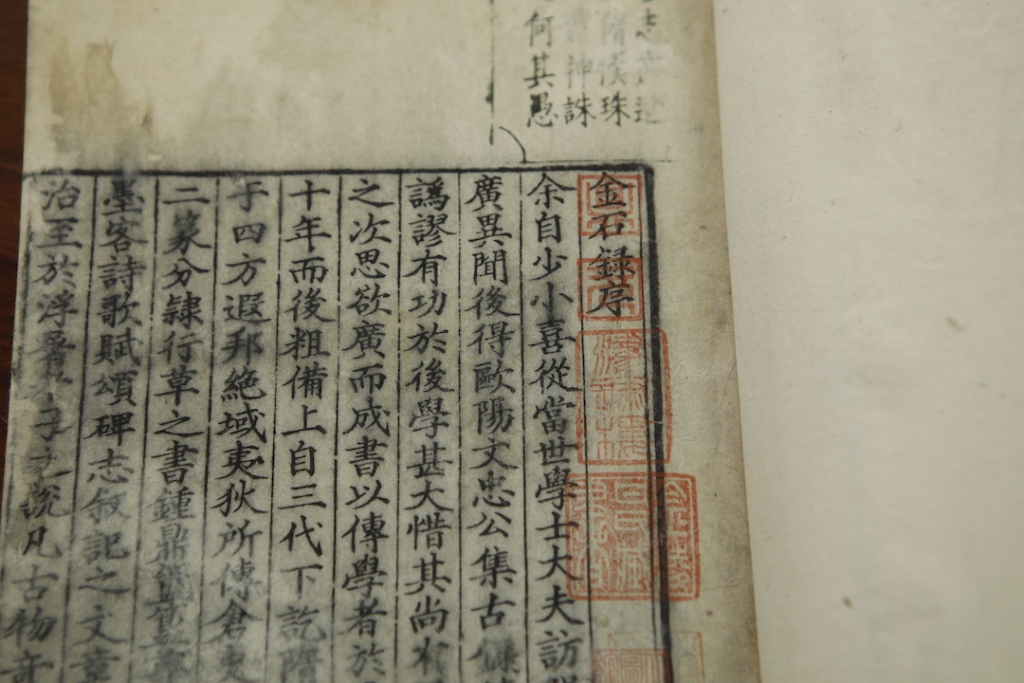

The earliest existing version of "Jinshilu" is the one printed by Longshu Junzhai in the Chunxi period of the Southern Song Dynasty. Its 30 volumes are now kept in the National Library of China. It is not only an early printed version, but also the only existing complete Song Dynasty edition. It was selected into the first batch of national precious ancient books list.

For centuries, the complete 30-volume edition was generally believed to have been lost until its rediscovery in the 1850s. How did this national treasure of a document make its way from private collection to rediscovery and ultimately to the public domain? What are the differences in content between the 30-volume edition and the 10-volume edition?

"The Record of Metal and Stone is an important work in the fields of epigraphy and bibliography, and the contents of twenty of its thirty volumes are not found in other versions. It is a unique copy in China and has irreplaceable documentary value," said Chen Hongyan.

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

Legendary ancient books, from private collection to national treasure

Q: This complete Song Dynasty edition of the Record of Metal and Stone, described by Zhang Yuanji as "unique in the world," was originally discovered and acquired by the National Library. What are the little-known stories behind this discovery?

Chen Hongyan: The 30-volume edition of the Jinshilu is rarely mentioned in Yuan and Ming dynasty documents, and its presence is rarely found in various catalogs. Therefore, for a long time, the academic community generally believed that only 10 volumes survived from the late Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty, and that the complete 30-volume edition had been lost.

This situation changed around 1950. In Nanjing, there was a famous library called Jindailou. The owner, a surnamed Gan, had amassed a vast collection over four generations, with the catalogue alone comprising eighteen volumes, and the total collection exceeding 100,000 volumes. The Gan family had a habit of not listing particularly valuable and rare books in the public catalogue, perhaps out of concern for others. Because of this, important Song Dynasty printed editions like the Jinshilu, despite their existence, remained largely unknown.

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

The discovery of these thirty volumes is a story filled with legends and stories. During the Taiping Rebellion, Jindai Tower suffered a fire that destroyed many of the books in the collection, but this set of books fortunately survived. However, the Gan family's heirs did not delve deeply into the collection itself. In the 1950s, a military unit reclaimed the Jindai Tower property for office use, forcing the Gan family to clear out the books. They had originally intended to have a relative, former National Central University professor Lu Qian, assess the value of the books, but Lu was ill and unable to attend the appraisal. So, they instead invited used books dealer Ma Xing'an to inspect the goods and negotiate a price. A few days later, Ma brought two companions to the Gan residence, one of whom was a water conservancy expert and bibliophile named Zhao Shixian.

Book collector Zhao Shixian (Photo source: Internet)

At the time, these books were being sold by the pound, at a very low price, equivalent to 2,000 yuan per pound in old currency, or about 20 cents per pound today. Zhao Shixian and others thus acquired a collection of books, including the "Jinshilu." Later, Gan Wen, a descendant of the Gan family, asked Mr. Lu to return and search for any particularly valuable books worth preserving. While examining the book, Mr. Lu noticed the inscription "嘉䋭" (Jia 䋭) on the front, mistaking it for "嘉靖" (Jiajing) (the two characters are similar in shape). He assumed it was a Ming Dynasty edition, of modest value, and so ignored it.

After acquiring the precious book, Mr. Zhao Shixian and the bookseller, Ma Xing'an, had a disagreement: Mr. Ma wanted to sell it for a profit, while Mr. Zhao believed such a treasure must be donated to the nation. However, as he was not particularly skilled in textual criticism, Zhao Shixian decided to ask Mr. Zhang Yuanji, an expert in ancient book editions, to authenticate and write a postscript. Through Mr. Gu Tinglong of the Shanghai Library, Mr. Zhao solicited Mr. Zhang Yuanji, a textual criticism expert, to authenticate the book.

Upon seeing the book, Zhang Yuanji was thrilled, confirming it was indeed the complete 30-volume Song edition, long thought lost! He penned a lengthy postscript of approximately 1,600 words, far exceeding the typical length of a postscript. In it, he elaborated on the value of the edition, declaring it "a unique copy," and fully commended Zhao Shixian's generosity in donating it. This postscript has become a crucial document for the circulation and study of the book.

The book was later brought to Shanghai, where it was appraised and highly valued by Zheng Zhenduo, then Vice Minister of Culture. Zheng Zhenduo, himself a bibliophile and bibliographer, had salvaged numerous valuable documents during Shanghai's "isolated island" period in the last century. Deeming it too risky to mail such a precious rare book, he personally escorted it back to Beijing, where it eventually became part of the collection of the Beijing Library (now the National Library of China).

Thus, this important Song Dynasty edition, nearly thought lost during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, ultimately became a valuable part of the National Library's collection. The Jinshilu is a seminal work in epigraphy and bibliography, and twenty of its thirty volumes contain content not found in other versions, making it a unique copy in China and possessing irreplaceable documentary value. This is the legendary journey of a rare and precious book, from private collection to rediscovery, and ultimately to national preservation.

The difference between the 30-volume edition and the 10-volume edition

Question: The thirty volumes of "Jinshilu" are a rare complete Song Dynasty edition. We know that "one leaf of Song Dynasty edition is worth one tael of gold". What is the unique value of this Song Dynasty edition?

Chen Hongyan: From a textual criticism perspective, Song editions possess significant cultural and documentary value. Due to their age and rarity, Song editions are inherently precious cultural relics. More importantly, as the closest version to the original, they minimize the chance of errors during the copying process, preserving the original text to the greatest extent possible. While revisions may have occurred during later printing, Song editions remain the most reliable basis for restoring the original text. The 30-volume edition of "Jinshilu" (Records of Gold and Stone) is the Longshu County Zhai edition from the Chunxi period of the Southern Song Dynasty, an ancient book printed in present-day Anhui Province. For example, this edition is likely the first edition printed after Zhao Mingcheng completed the book, and therefore holds significant value in many respects.

The Jinshilu (Records of Bronze and Stone Inscriptions) is divided into two major parts. The first ten volumes are a catalog, cataloging 2,000 items, including bronze and pottery vessels, steles, and epitaphs. Many of these items no longer exist or are incorrectly documented, making this section the earliest and most accurate historical record of exceptional documentary value. The last twenty volumes are a postscript, containing 502 summaries of important bronze and pottery vessels, steles, and epitaphs. These are Zhao Mingcheng's examination and commentary of the artifacts he encountered, equivalent to modern academic research notes. They preserve much original information inaccessible to later generations and provide a valuable reference for epigraphy, philology, and historical research.

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

Comparisons between the 30-volume and 10-volume editions reveal numerous valuable differences. For example, some missing text in the 30-volume edition was supplemented in later editions. There are also additions, deletions, and revisions. These differences reflect the impact of revisions during different printing periods. Scholars previously believed there were two versions: the Longshu Junzhai edition during the Chunxi period and the reprint by Zhao Bujian 30 years later. However, it is more likely that the same block was repaired and revised, resulting in different printings. The extant 30-volume edition has clear handwriting, indicating an earlier edition, while the 10-volume edition has slightly blurred text and includes corrections to missing text from earlier editions. This process of textual evolution provides tangible evidence for the study of the circulation and revision of ancient books.

The rediscovery of the 30-volume Song edition of the Jinshilu provides crucial evidence for in-depth research into the text's origins and the correction of later errors. Since it was not reprinted during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, most copies circulated later. While some are excellent, some have been labeled "laden with errors" by the General Catalogue of the Complete Library in the Four Treasuries. Therefore, this pre-printed Song edition not only allows us to glimpse the text's original form but also serves as a crucial foundation for restoring its accuracy and tracing its transmission, possessing significant academic significance and archival value.

Question: There seems to be a lot of difference in content between the 30-volume edition and the 10-volume edition. So what are the contents of the extra 20 volumes in the 30-volume edition?

Chen Hongyan: The ten-volume edition of the Song Dynasty edition of the Jinshilu held by the Shanghai Library had been previously published. When Zhu Dashao collected this edition, he discovered that only ten volumes remained, and mistakenly identified it as "missing the second half of the twenty volumes." He was unaware that this ten-volume edition actually comprised the middle section of the thirty-volume edition. The first ten volumes of the complete thirty-volume edition of the Jinshilu serve as the table of contents, while the last twenty volumes serve as the epilogue. Therefore, the ten-volume edition held by the Shanghai Library contains volumes 11 through 20 of the thirty-volume edition.

During his collection, Zhu Dashao discovered that this ten-volume edition had been forged, and the forger's technique was quite sophisticated. The dealer removed the character "十" from "Volume 11" and replaced it with "Volume 1." To conceal the authenticity of the forgery, the entire text was moved upward. A comparison with the 30-volume Song edition in the National Library's collection reveals that the postscript is positioned higher, providing irrefutable evidence of forgery. Consequently, this edition lacks Zhao Mingcheng's original preface, the table of contents for the first ten volumes, and the postscript for the last ten volumes.

The first ten volumes of the thirty-volume catalog (a total of 2,000 entries) are of extremely high academic value: these catalogs are arranged in chronological order and fully record the information on the bronze and stone artifacts that existed at the time and that Zhao Mingcheng and Li Qingzhao had examined. They are an important basis for studying the bronze and stone artifacts of the Song Dynasty. In his preface, Zhao Mingcheng also made an objective evaluation of Ouyang Xiu's "Collected Ancient Records" - he recognized the importance of "Collected Ancient Records" and his own love for it, but also pointed out that it had the problem of "not being arranged chronologically" and contained some errors and omissions in the content. For this reason, when compiling "Collected Ancient Records", Zhao Mingcheng deliberately corrected these shortcomings of "Collected Ancient Records" and clearly compared the differences between the two books in the preface, making "Collected Ancient Records" a more systematic and accurate catalog of bronze and stone artifacts, leaving behind extremely valuable documentary materials for future generations.

Overall, the thirty-volume edition, complete with a complete catalog and twenty volumes of postscripts, offers valuable documentation and materials worthy of in-depth study by experts, scholars, and epigraphic enthusiasts. The catalog allows researchers to explore the whereabouts of artifacts listed in the catalog but currently unknown; the postscript also allows them to understand Zhao Mingcheng's evaluations and value judgments on various epigraphic artifacts, furthering their research on Song Dynasty epigraphy.

Q: Many of the bronze artifacts described in the book no longer exist, and we can only perceive their former appearance through the text in the Jinshilu. It's true that "paper and ink outlive bronze and stone." Could you elaborate on the bibliographical value of the Jinshilu?

Chen Hongyan: Indeed, throughout human history, countless precious cultural relics have witnessed the rise and fall of civilizations, their transformations, and their transformations. However, due to various factors, including natural disasters and human destruction, many cultural relics have been lost. Some important artifacts, such as bronzes, may have a clearer lineage of transmission due to their large size and relatively clear circulation records. The fact that the inscriptions on these lost bronzes have survived to this day through the records in the Jinshilu is truly remarkable.

The Jinshilu also contains numerous records of paper artifacts such as steles and rubbings. The example of the "Shence Army Stele" in the National Library's collection directly demonstrates the empirical value of the thirty-volume catalog. While the "Shence Army Stele" is commonly referred to today as the "Emperor's Tour to the Left Shence Army, Commemorating His Virtue," the Jinshilu uses a different name. Volume 10, 1863 and 1864 of the Jinshilu record "Tang's Tour to the Left Shence Army, Part 1 and Part 2." It is known that the two volumes Zhao Mingcheng and Li Qingzhao saw were complete. The "Shence Army Stele," written by Liu Gongquan at the age of 66, was erected in a forbidden area of the Tang Dynasty palace. Its contents record the Tang Emperor's tour of the Left Shence Army. From a calligraphic perspective, the stele is considered a masterpiece of "both the author and the writing are mature." From a historical perspective, the inscription also documents the mutual support and cultural integration between the Tang Dynasty and the Uighur leader regime, possessing both calligraphic and historical value. According to the catalog of the 30-volume edition, the "Shen Ce Army Stele" was originally divided into two volumes, of which only one remains today, making it the only surviving copy. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the last entry in the 30-volume "Jinshilu" relates to Japan, making it the only document of the time to refer to anything outside of China, making it quite unique.

Like earlier historical catalogs such as the "Book of Han: Records of Arts and Literature" and the "Book of Sui: Records of Classics," the historical value of the "Jinshilu" catalog lies in its faithful record of the existing literature of the time, providing a crucial means for restoring the true nature of ancient texts. It provides a crucial reference for distinguishing the surviving and lost ancient books and verifying their authenticity. By systematically sorting out discrepancies among historical catalogs, we can not only trace more accurate original cataloging information but may even rediscover clues to documents thought long lost. Future scholars comparing the 2,000 catalog entries and 502 postscripts in the 30 volumes of the "Jinshilu" with existing epigraphic artifacts would be a remarkable academic contribution.

Famous seals restore the millennium "history"

Q: The book contains collection seals of famous historical figures such as Tang Bohu and Wang Shizhen. How can these collection traces help us restore the thousand-year history of this national treasure?

Chen Hongyan: Collected seals hold significant value in the documentation of ancient books. They not only mark the identities of successive collectors but also bear witness to the transmission of texts, informing modern readers of their lineage. Book collectors often affix their own seals to rare books to identify them as belonging to their collection. However, historically, this has presented some complexities: some collectors, cherishing their books and hoping for their best condition, or concerned about contamination from inferior ink, chose not to affix their seals until the time of transfer. Other seals may be questionable, such as Tang Yin's seal in this book, which has been labeled "suspected forgery" by scholars, reflecting the academic community's cautious approach to collection appraisal.

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

The seals of Wang Shizhen and the Gan family's Jindailou collection in this book clearly outline a chain of collections from the Ming Dynasty to modern times, providing crucial clues for the study of collecting history. The inscription on Tang's "Youfei Hall," "Reading permitted, not borrowed," vividly reflects the traditional bibliophile concept of "secret treasures," a direct echo of the Tianyi Pavilion's rule that books must not leave the collection. Another inscription within the book compares the preciousness of the book to the "Sui Hou Pearl," even warning against "divine punishment for damage," demonstrating the collector's cherishment of the precious book.

Records of Inscriptions on Metals and Stones, Chunxi Period, Southern Song Dynasty, Longshu Junzhai Edition, National Library of China

In terms of the physicality of this edition, this book also bears traces of historical restoration. Significant water stains are visible in the preface, and several inscriptions and inscriptions were partially damaged during binding and trimming (for example, the edge of the inscription "唐氏有匪堂" is slightly lost). This reflects that early restorations prioritized the preservation of the text within the frame, often at the expense of marginal information. Today, the preservation of ancient books adheres to the principles of "restoring the old as it was" and "minimizing intervention," striving to preserve all traces of history. Compared to many Song Dynasty books, this copy has suffered no damage from insects and other infestations, making its overall state of preservation exceptional. However, comparison reveals water stains and tears, and the resulting restoration has been performed through trimming. While this has preserved the integrity of the text, it has also gradually diminished the original's physical form. This evolution of text and physical form embodies the life cycle of ancient books: it carries scholarly content while also embodying the traces of collection, restoration, and conservation throughout the ages, together forming a visible "history of transmission."

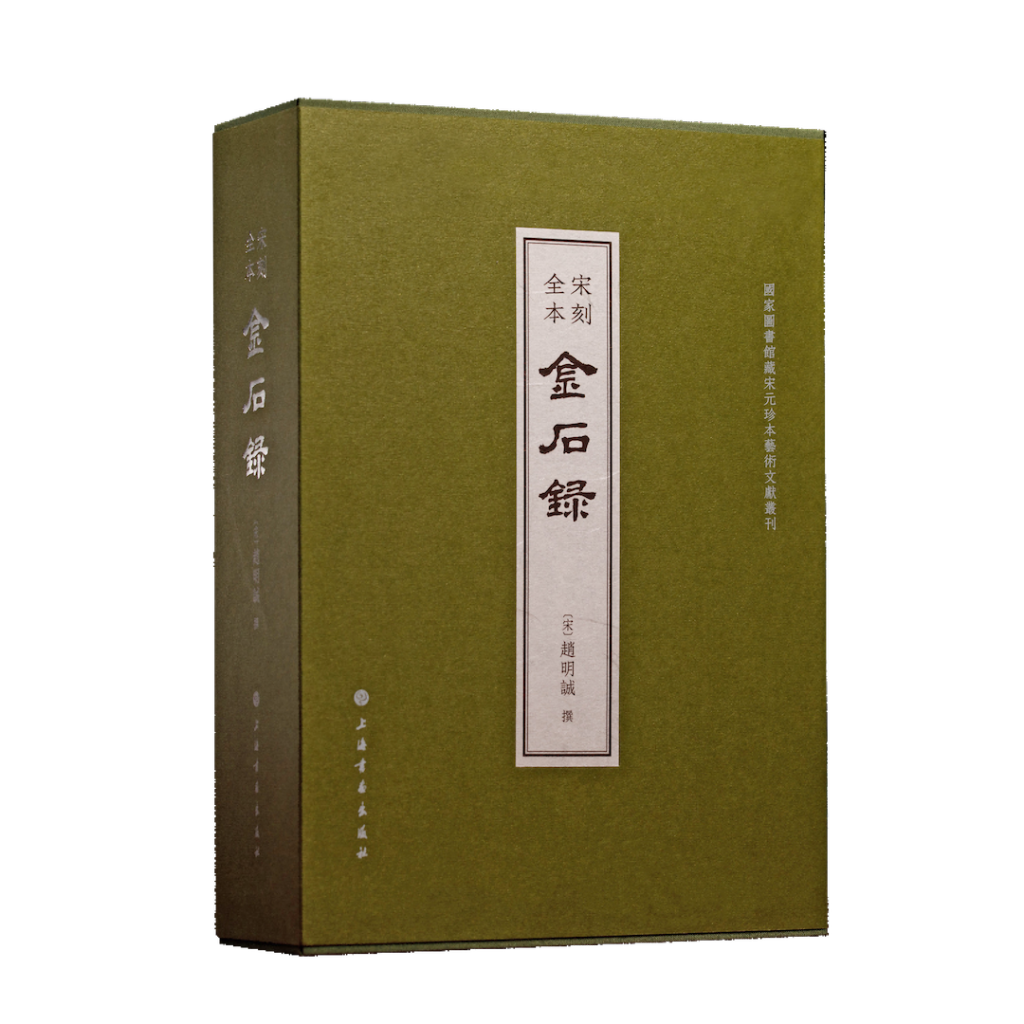

The complete Song Dynasty edition of "Jinshilu" was published by Shanghai Painting and Calligraphy Publishing House.