Wang Anshi of the Northern Song Dynasty once visited the ruins of Gu Yewang's former residence in the Southern Dynasties, but due to time constraints, "I only had a brief visit and no time to investigate..." (Zhao Mengfu wrote in "Baoyun Temple Record"), so he sighed: "There are only a few pavilions on the lake, but no trace of Yewang's residence." This sigh of a thousand years of time and space reflects the admiration of later generations for this hermit and encyclopedic scholar of the Southern Dynasties.

Gu Yewang was a renowned geographer, philologist, historian, calligrapher, and painter during the Liang and Chen dynasties of the Northern and Southern Dynasties. His work, Yu Pian, is China's oldest extant dictionary in regular script, and his compilation of Yu Di Zhi, a national gazetteer, earned him the title of "a great scholar of his generation" and the title of "Confucius of Jiangdong. " The Paper's "Cultural China Tour" recently visited Jinshan Pavilion Forest to rediscover the cultural legacy of this renowned hermit amidst the mists of Jiangnan.

From the mound of "Reading Pile" in Tinglin, to the twisted branches in the Ancient Pine Garden, to the "Yu Pian" spanning China, Japan and South Korea, and the "Auspicious Responses Picture" in the Dunhuang fragments, Gu Yewang's life trajectory and spiritual legacy still echo between Jiangnan and East Asian civilizations.

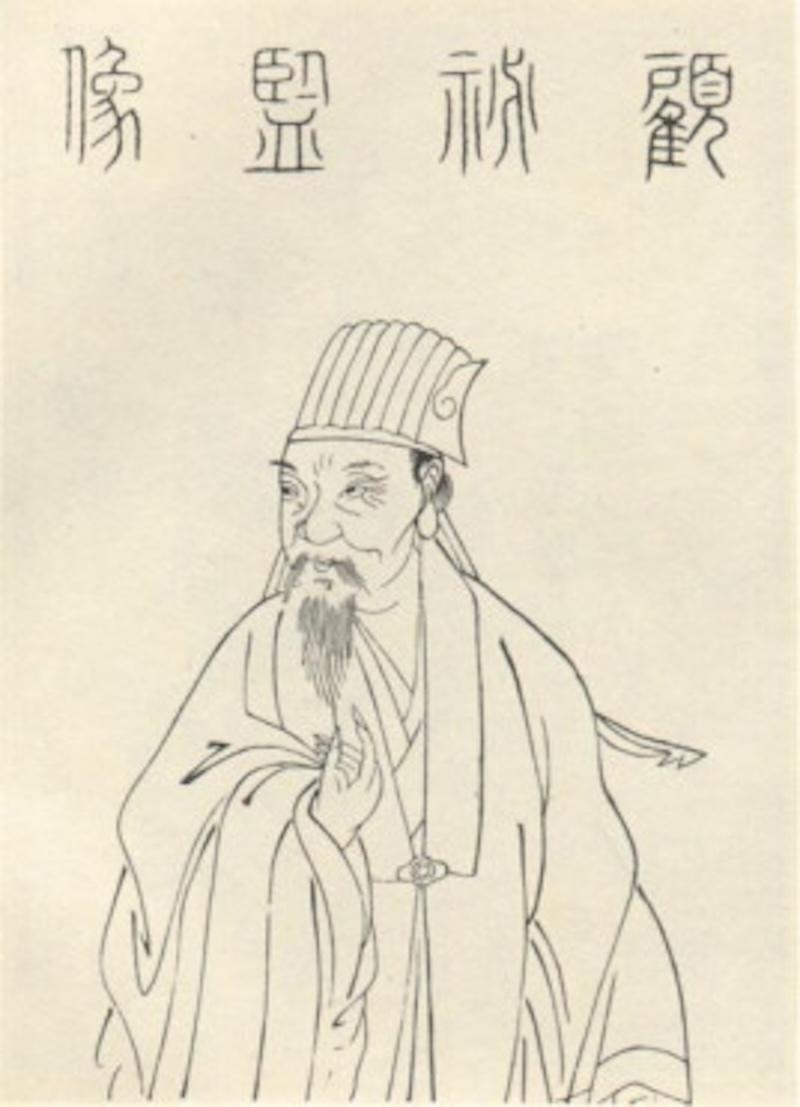

Statue of King Gu Ye

Gu Yewang was born in the 18th year of Tianjian in the Southern Liang Dynasty (519) and died in the 13th year of Taijian in the Chen Dynasty, which was the first year of Kaihuang in the Sui Dynasty (581), at the age of 63.

Gu Yewang was born into the Gu family of Tinglin, Haiyan County, Wu Commandery, one of the four major surnames of the Wu Commandery in Jiangdong. His ancestor, Gu Yong, Prime Minister of the Sun Wu during the Three Kingdoms period, was born near Guxu Pond in Tinglin, Haiyan. Both his father and grandfather were renowned for their Confucian scholarship. According to the Book of Chen, "Yewang was studious from a young age. At seven, he had read the Five Classics and grasped their main points. At nine, he could write. He once composed a 'Sun Fu,' which impressed the commander Zhu Yi." Before the age of twenty, Gu Yewang spent his entire life studying and learning—"he grew up thoroughly versed in classics and history, memorizing them with utmost precision, and mastered astronomy, geography, yarrow and tortoise shells, and worm-shaped seal characters, becoming proficient in everything."

At the age of twenty, Gu Yewang began his official career. He was invited as a guest by the Yangzhou Governor, Prince of Xuancheng, Xiao Daqi (son of Xiao Gang, who was made Crown Prince after Xiao Gang ascended the throne). Among the guests was the literary scholar Wang Bao. Gu Yewang was a skilled painter. Once, while the Prince of Xuancheng was building a school, he commissioned Gu Yewang to paint portraits of ancient sages and Wang Bao to write inscriptions in praise of them. These two masters were hailed by contemporaries as "two unique talents."

Afterward, he was commissioned by Crown Prince Xiao Gang to compile the Yu Pian (Yu Pian) over a five-year period. He single-handedly compiled this 30-volume work, laying the foundation for Chinese character civilization in East Asia. After the Hou Jing Rebellion, Gu Yewang returned to Tinglin, the hometown of his ancestor Gu Yong, where he lived and wrote for a long time, naming himself "Tinglin." His 34th-generation descendant, Gu Yanwu, also took the name "Tinglin" in homage to his ancestor.

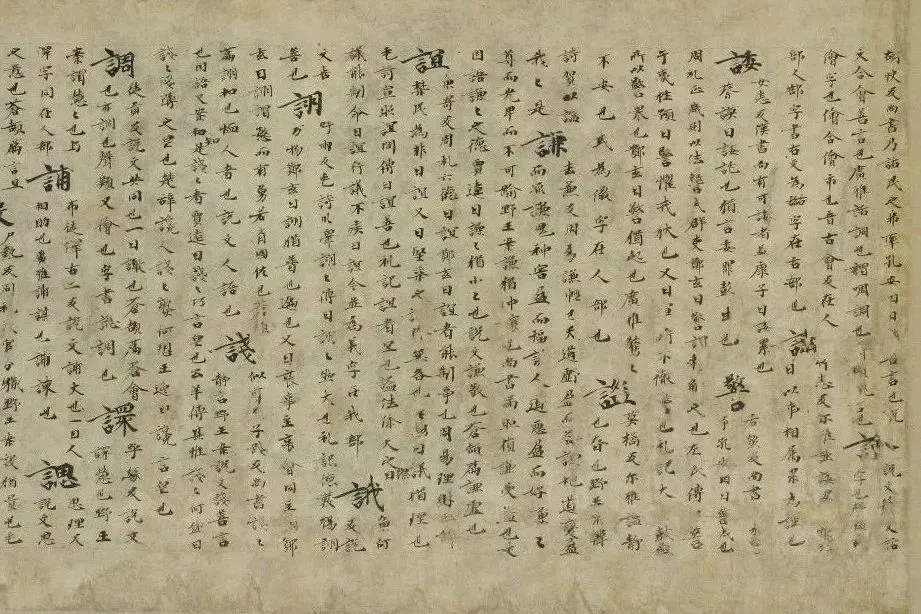

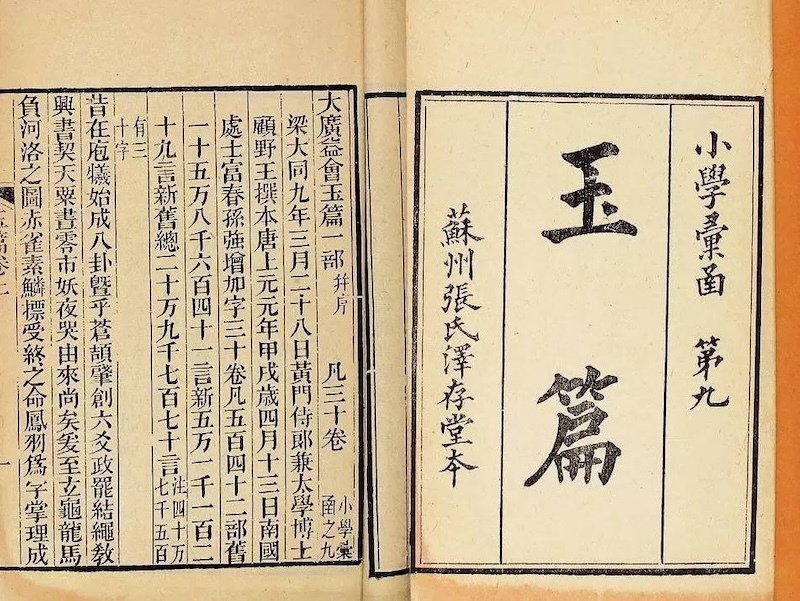

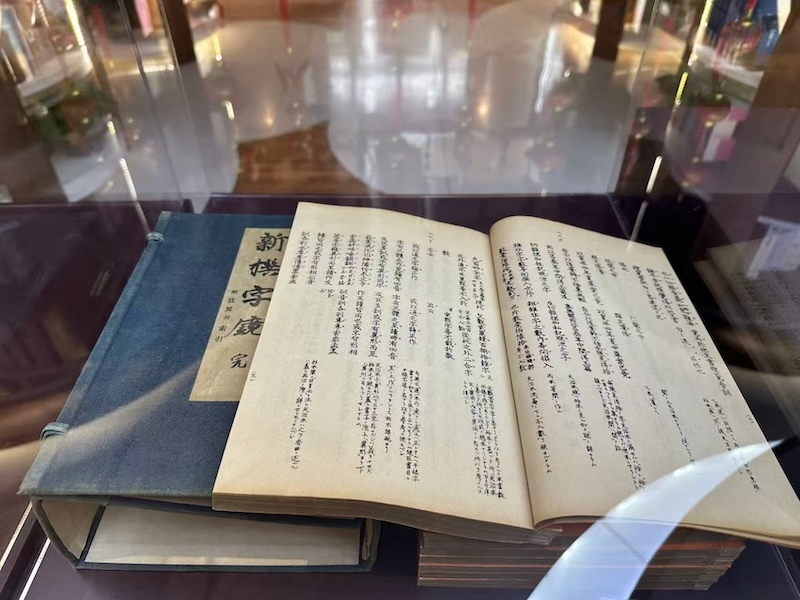

Tang Dynasty manuscript of Yu Pian

Reading piles, Gu Yewang lives in Tinglin

In Jinshan Tinglin Town, there is a relic called "Reading Pile".

The "Reading Pile" is located at the intersection of Sipingnan Road and Datong Road in Tinglin Town. If you don't pay attention, you will think it is just a mound shaped like a hill with dense vegetation. But when you learn that this is the place where Gu Yewang, who we are going to visit, built a thatched house and read and wrote, you can't help but feel awe.

"Dushudui" was originally named Dushudun. In the Song Dynasty, "dun" was changed to "dui" to avoid taboo. Local people call it "Dasishan". It is one of the earliest private gardens with written records in Shanghai.

The ruins of Gu Yewang's "Reading Pile" located in Jinshan Tinglin.

According to Jiang Zhiming, director of the Shanghai Gu Yewang Cultural Research Institute and professor at East China University of Science and Technology, the "Book Pile" is the only surviving relic of the ancient "Eight Scenic Spots of Tinglin." In recent years, Tinglin Town has used Gu Yewang as a cultural landmark, rebuilding the Tinglin Academy, erecting a statue of Gu Yewang, and opening Gugong Square, striving to rekindle the scholarly past hidden in the misty rain of Jiangnan.

Next to the "Reading Pile" is the statue of Gu Yewang on Gugong Square.

There is a passage in "Gugong Square" that says that in the 14th year of the Tang Dynasty's Dazhong period, monks from Baoyun Temple in Tinglin unearthed a fragment of a stele that read: "On the high ground south of the temple, Gu Yewang once compiled the "Geographical Records" here." (From "Records of Baoyun Temple in Songjiang")

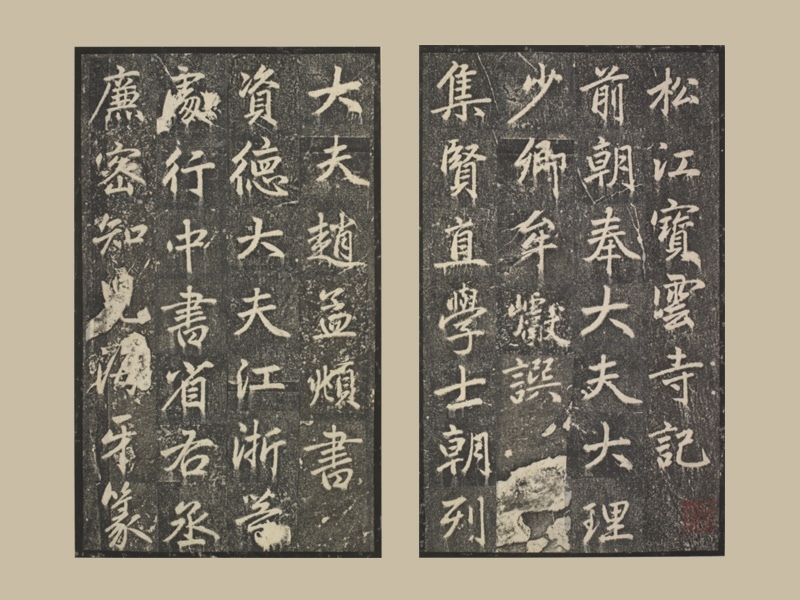

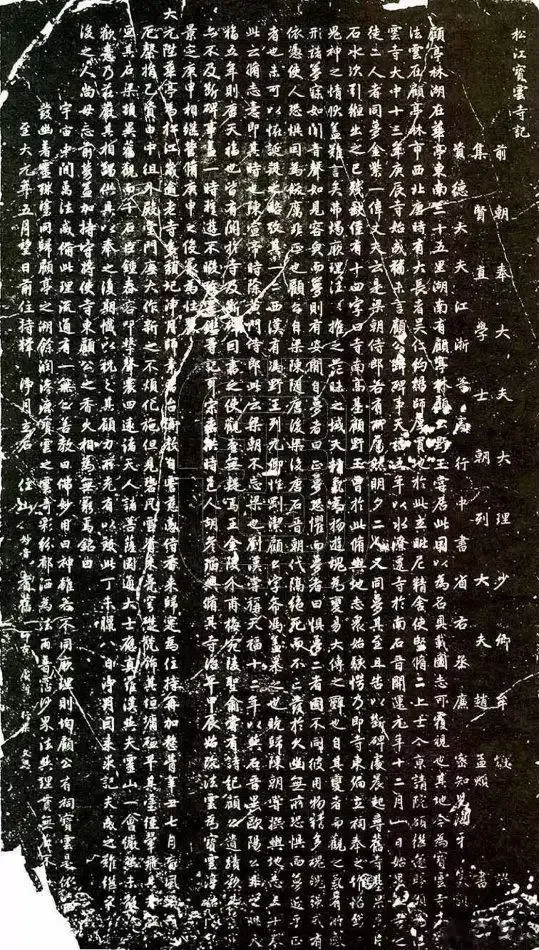

Zhao Mengfu's "Songjiang Baoyun Temple Stele Album" (Qing Dynasty rubbing) is in the collection of the Palace Museum.

The compilation of the "Yu Di Zhi" (Geographical Records) dates back to the Six Dynasties period, when geographical records flourished. However, they were numerous, contained much repetitive content, and lacked a systematic structure. According to the "Book of Sui: Records of Classical Books," Gu Yewang "copied and compiled the opinions of various scholars" to create the 30-volume "Yu Di Zhi," which can be considered "a comprehensive collection of geographical texts since the Han and Wei dynasties."

This book not only examines the natural beauty of mountains and rivers and the history of counties and cities, but also pioneered the method of citing literature and noting the source, which became a standard for local chronicles in later generations. Although the original book was lost in the Song Dynasty, the lost text can be found in citations in documents from the Tang and Song dynasties onwards.

More importantly, the origin of the Chinese character "沪" (Shanghai) can also be traced back to Gu Yewang. In his book "Yu Di Zhi," he detailed the bamboo fishing gear called "hu" (meaning "Hu"): "Bamboos are placed in a row in the sea, woven with ropes, with two wings extended toward the shore. They are submerged by the tide and emerge when the tide recedes. Fish and crabs follow the tide, but are blocked by the bamboos, so they are called hu." This is considered the earliest written source for Shanghai's abbreviation, "Hu."

Despite the passage of time, the inscription on the broken stele, "Temple South High Base," still corresponds to its current location. A reporter from The Paper, following Jiang Zhiming from the "Reading Mound" at Guyewang along Siping South Road, spotted the Baoyun Temple flagpole stone, nearly hidden in front of residential buildings.

The flagpole stone of Baoyun Temple in front of the residential building

Baoyun Temple, built in the 13th year of the Tang Dynasty's Dazhong reign (859), is said to have once comprised 1,048 magnificent Buddhist temples stretching for several miles. It was known as one of the "five most famous temples in Jiangnan, and the most prestigious in Huating." However, due to the vicissitudes of natural disasters and war, Baoyun Temple was repeatedly rebuilt and destroyed. After millennia, only a few remains remain.

Baoyun Temple Bridge

Among them, the Lengyan Pagoda (also known as the "Flying Pagoda") within the temple, one of the Eight Scenic Spots of Tinglin, now only has its central pillar, the "Stone Sutra Pillar," preserved at Tinglin Primary School. The more famous Songxue Stele (also known as the "Zi'ang Stele"), a memorial to the Baoyun Temple in Songjiang, was written by Mou Yan and inscribed by Zhao Mengfu during the renovation of Baoyun Temple in the Yuan Dynasty. Today, only the stele's base, cap, and remaining fragments remain in the Jinshan District Museum.

A replica of the "Zi'ang Stele" in the Jinshan District Museum

Rubbing of Zhao Mengfu's "Record of Baoyun Temple in Songjiang"

The inscription, as revealed by surviving rubbings, chronicles the history of Baoyun Temple in Songjiang and the restoration of the temple by its abbot, Jingyue, during the Yuan Dynasty. The inscription repeatedly alludes to Gu Yewang's connection to Tinglin. The account of Gu Yewang's writing of his "Geographical Records" here and his strange experience of "the broken stele reappearing in a dream" further enhances the sense of reverence and sacredness.

Gu Yewang's "Reading Pile"

From the Toothpick Pine to the Ancient Pine Garden: A Cultural Dialogue Between Two Pines

Two pine trees are renowned in Tinglin: Gu Yewang's "Tooth-Pickling Pine," and Yang Weizhen's "First Pine in Jiangnan," planted in the late Yuan Dynasty. The former has been lost to time, while the latter still stands tall in the ancient pine garden. One a part of history, the other a part of the present, both deeply rooted in the cultural memory of this land.

According to the Songjiang Prefecture Chronicle, compiled by Chen Jiru during the Ming Dynasty, "There was a large tree called the Pick-tooth Pine near the Book Pile, which still existed in the early Chenghua period (1465)." This pine tree not only reflects Gu's daily life, but also, through its association with reading and writing, imbues it with the aura of a scholar of refinement and simplicity. The Pick-tooth Pine has thus become a symbolic image of Gu Yewang's cultural image, reflecting the ideal of Southern Dynasties literati who retreated to the mountains and cultivated themselves through literature.

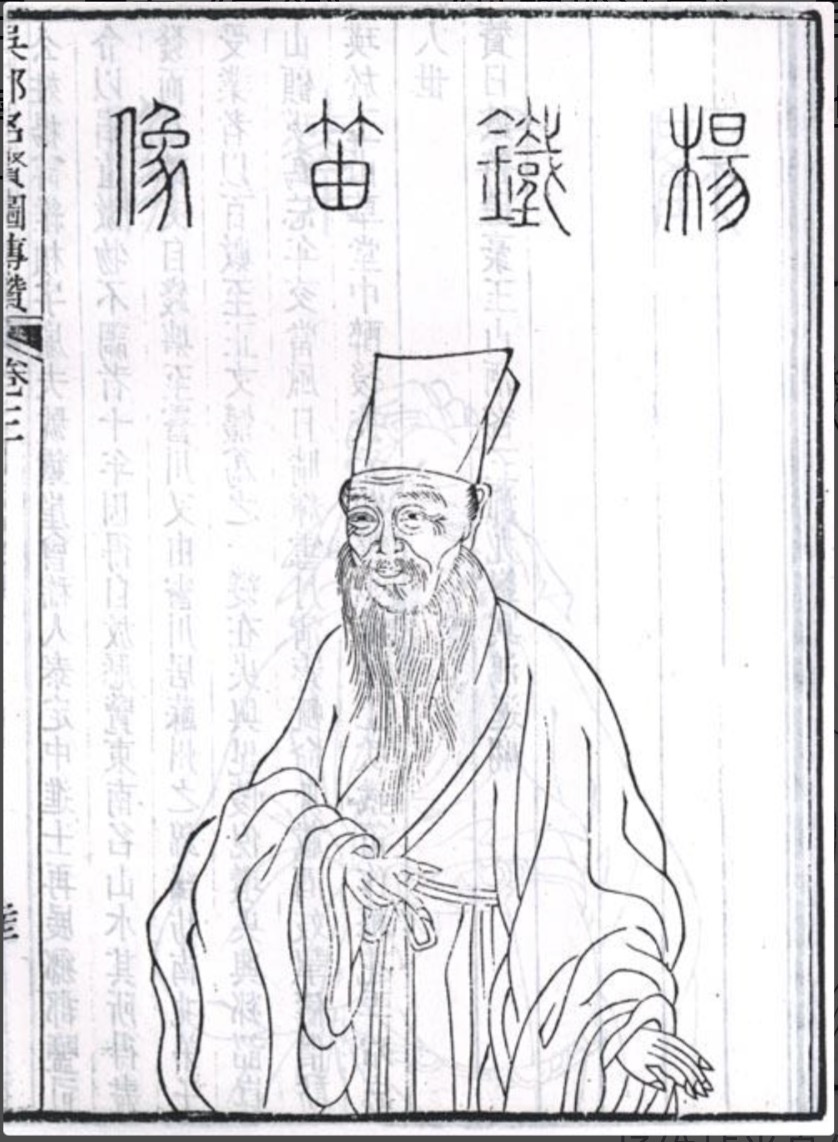

Portrait of Yang Weizhen

In 1350, the tenth year of the Zhizheng reign of the Yuan Dynasty, the writer, calligrapher, and painter Yang Weizhen (1296-1370), who called himself "Iron Cliff Hermit," visited the Yewang Study Terrace in Tinglin. Legend has it that on his 55th birthday, he personally planted a Podocarpus macrophylla to commemorate his birthday, also known as the "Iron Cliff Pine." Thereafter, he resided on East Street in Tinglin, where he immersed himself in the mountains and forests and met literary friends like Tao Zongyi.

An introduction to the "Ancient Pine Garden" on Fuxing East Road in Tinglin. The calligraphy comes from Hu Boping, a calligrapher and employee of the local supply and marketing cooperative in Tinglin.

This "Iron Cliff Pine," said to have been planted by Yang Weizhen, is located within the "Ancient Pine Garden" on present-day Fuxing East Road. The garden was built in 1986, with a stream running through its southern section. At the entrance, an introduction written by calligrapher Hu Boping (1933-2020), an employee of the Tinglin Supply and Marketing Cooperative, tells the history of this "First Pine in Jiangnan" and the "Ancient Pine Garden." Upon entering, passing the screen wall and connecting corridors, a small scenic spot emerges. The ancient Podocarpus is leaning and supported; adjacent to it to the north is a thick-shelled pine and an ancient well. A nearby stele explains that the thick-shelled pine was planted during the Tongzhi reign of the Qing Dynasty.

According to legend, the "Iron Cliff Pine" was planted by Yang Weizhen

The garden is quiet, the only sound being the rustling of fallen leaves as staff sweep up the trees. For Yang Weizhen, this pine tree is more than just a garden ornament for a hermit; it evokes the spirit of a sage. In 1360, Yang Weizhen wrote in his "Reading Pile Notes": "When I arrived in Song, my first admiration was for Gu Yewang, the one who read books amidst the verdant pavilions and forests, though I have never been there." The poem clearly expresses his reverence for Gu Yewang. The parallel between Yang Weizhen's hand-planted "Iron Cliff Pine" and Gu Yewang's "Pick Tooth Pine" embodies the profound historical reflections of Yuan Dynasty literati and represents a continuation of Gu Yewang's cultural ethos and life attitude.

In the "Ancient Pine Garden", the "Iron Cliff Pine", the thick-shelled pine and the ancient well form a group of scenery.

Gu Yewang and Yu Pian: A Dictionary's Millennial Echoes

In addition to his geographical works, another great work handed down by Gu Yewang is "Yu Pian" - a systematic Chinese character dictionary in the Southern Dynasties period. It was written more than a thousand years earlier than "Kangxi Dictionary" and is an important reference book for literacy and teaching in China since the Sui and Tang Dynasties.

There is a "Yusu Bridge" in Tinglin Town, which is taken from Cangjie's "Yusu Bridge" which means "raining millet from the sky", as if quietly telling the continuation of Gu Yewang's writing career.

During the Southern and Northern Dynasties, during Gu Yewang's lifetime, the intermingling of various ethnic groups led to a chaotic use of Chinese characters. Furthermore, the rise of Buddhism introduced many new characters and words, and the shift from seal script and clerical script to regular script also created inconveniences for daily reading and writing. Therefore, standardizing character forms and unifying standards became imperative. Emperor Wu of Liang appointed Gu Yewang as a doctor of the Imperial Academy, tasking him with this arduous task.

Young Gu Yewang gladly accepted the offer. He read extensively, collecting and researching the similarities and differences in the forms and interpretations of characters from the Han, Wei, Qi, and Liang dynasties, selecting and editing them. He worked tirelessly for five years, completing the manuscript in the ninth year of the Datong reign of Emperor Wu of Liang (543 AD). He was only 25 years old that year.

Yu Pian by Gu Yewang

The name "Yu Pian" is said to come from the teachings of Gu Xuan, the father of Gu Yewang: "Words are as precious as jade." Gu Yewang wrote in the preface to "Yu Pian": "If the literature is passed down for hundreds of generations, then the rituals and music can be understood; if it is spread across thousands of miles, then the heart's words can be conveyed." He knew very well that the power of words can not only be passed down for a long time, but also transcend thousands of miles of time and space, allowing people's hearts to communicate and their cultures to be connected.

According to researcher Jiang Zhiming, Li Si unified Chinese characters, Xu Shen compiled the first Chinese small seal script dictionary, "Shuowen Jiezi," which included 9,353 characters, and Gu Yewang compiled the first regular script dictionary, "Yu Pian," which included 16,917 characters. These dictionaries had a profound impact on ancient Chinese philology, phonology, and exegesis.

The Yupian was not only widely circulated in China at the time, but also spread to Japan via the Sui and Tang envoys, profoundly influencing Japanese classical literature and kanji education. Japanese texts such as the Leiju Yoriyōshō frequently cite the Yupian, and the structure and radical classification system of Sino-Japanese dictionaries also draw inspiration from it.

The earliest introduction of the Gyokupian script to Japan can be traced back to the early Heian period. When the Japanese monk Kukai traveled to Tang Dynasty to seek Buddhist teachings, he brought the Gyokupian script back with Buddhist scriptures and stored it in a Shingon Buddhist temple in Koyasan. He then compiled the "Zhuanli Wanxiang Yizhi" (The Meaning of Seal and Li Scripts) based on it. From then on, the Gyokupian script began to circulate widely within Shingon Buddhist temples and gradually spread to all walks of life in Japanese society.

Different versions of "Yu Pian" are displayed in the display cabinets of Tinglin's "Yu Pian" Experience Hall.

By 891 AD, the official Japanese document "Kenzaishu Catalog" already recorded 13 volumes of the Gyokuppancho. These editions have become valuable collections of major Japanese book collections, such as the Imperial Household Agency's Archives and Mausoleums Department, the National Archives, and the Seikado Bunko, all of which have Song Dynasty editions or fragments.

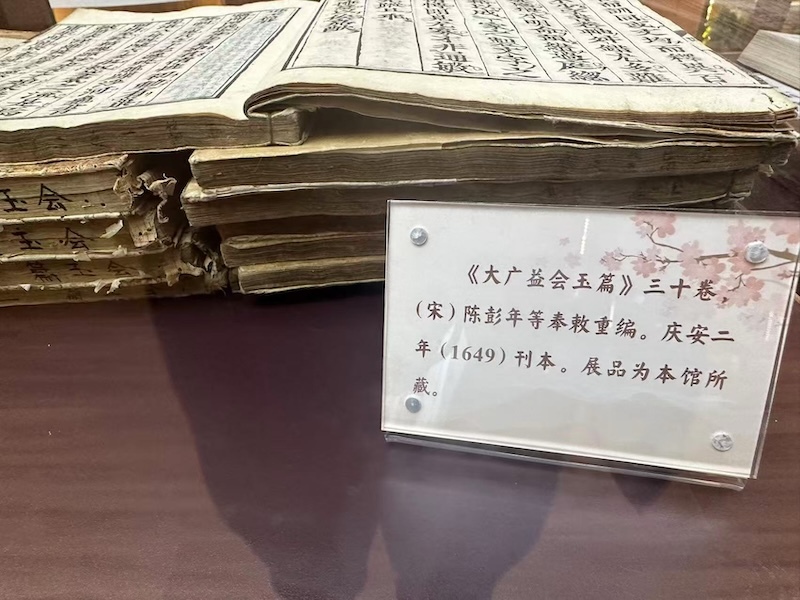

The "Da Guang Yi Hui Yu Pian" is displayed in the display cabinet of the Tinglin "Yu Pian" Experience Hall.

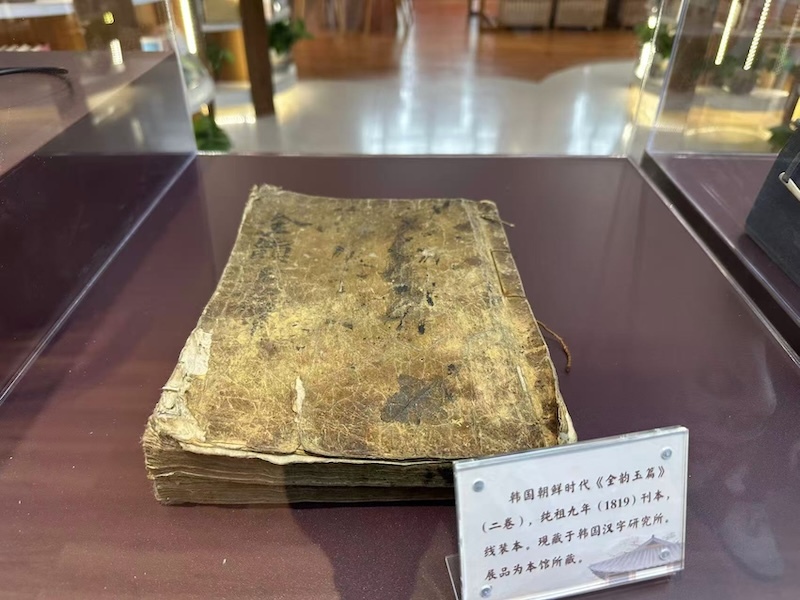

In the display cabinet of the "Yu Pian" Experience Hall next to the "Book Pile" in Tinglin, there are exhibits such as the 1883 photocopy of the 27th volume of the Tang Dynasty manuscript "Yu Pian" and the 1819 engraved version of "Quanyun Yu Pian" from the Joseon Dynasty in South Korea, quietly telling the influence of "Yu Pian" on the Chinese character cultural circle.

"Jeonyun Yupian" from the Joseon Dynasty of Korea

Painter Gu Yewang: Clues to the Dunhuang Fragments

Gu Yewang was not only a renowned literary figure but also a key figure in the tradition of calligraphy and painting. He was the teacher of Yu Shinan, one of the "Four Great Calligraphers of the Early Tang Dynasty." Ouyang Xun praised his calligraphy as "capable of emulating Zhong and Wang, mastering both styles."

Gu Yewang was also a "first-class painter in the Southern Dynasties". In Zhang Yanyuan's "Records of Famous Paintings of All Dynasties" in the Tang Dynasty, among the painters from Xuanyuan to Tang Dynasty, there was only Gu Yewang in the entire Chen Dynasty.

In addition to Yu Pian and Yu Di Zhi, there is also Fu Rui Tu, a work by Gu Yewang that appears in the Book of Chen: Biography of Gu Yewang. Today, all three are no longer available in their original form, which is an important reason why Gu Yewang is not well known to later generations.

So, what do Gu Yewang’s paintings look like?

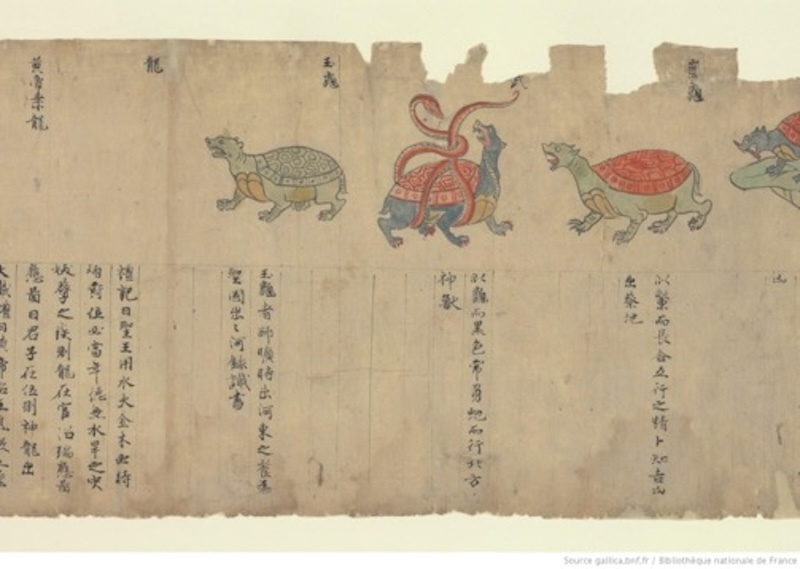

In the Dunhuang Grottoes, a fragment of the "Auspicious Responses Picture" numbered P.2683 has left vague clues for future generations.

Detail of the Dunhuang "Auspicious Responses"

This fragment, now housed in Paris, features yellowed paper and interlaced text and illustrations. Scholars have noted the repeated reference to "old illustrations not included," which aligns with Gu Yewang's style of writing, which he described as "adding illustrations and wefts"—in other words, he supplemented auspicious events not found in the old texts with illustrations. This is considered important evidence of the connection between the two.

Chen Shuang, a Peking University history PhD candidate and current researcher at the Institute of History at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, further pointed out in his recent research on the scroll that the fragment's arrangement, iconographic style, and regular division of text and image all embody the Southern Dynasties literati tradition of "combining books and text." If Gu Yewang's presence can be traced in Dunhuang remains, P.2683, "Auspicious Omens," may be a rare example.

In other words, the legacy of Tinglin's calligraphy lives on, and Gu's influence reaches far and wide in Dunhuang. This fragment is not only the only remaining copy of a Dunhuang text, but also allows Gu Yewang's scholarly method of "using illustrations to supplement text" to be revived across millennia.

Tinglin Old Street

Wang Anshi's "Pavilion on the Lake" evokes a thousand-year-old lament, yet Tinglin hasn't let Gu Yewang vanish into the dust of history. The pile of books, the tooth-picking pine, the fragments of the Jade Chapter, and the Dunhuang manuscripts embody the tenacity and enduring legacy of Jiangnan culture. Gu Yewang is both a symbol of Jiangnan scholars and a crucial founder of Chinese character civilization. Nearly a thousand years later, following the trail through Tinglin—lush green grass grows before the pile of books; in the ancient pine garden, the Podocarpus trees planted by Yang Weizhen remain leaning and vigorous. We are not merely searching for the remains of a Southern Dynasties scholar's former residence; we are exploring the extension of the Chinese cultural spirit.