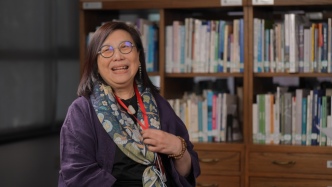

"I am Chinese, and also a Suzhou native." This heartfelt confession by architect I.M. Pei at the opening of the Suzhou Museum 20 years ago reveals his deep connection to the culture of his homeland. As a descendant of the Pei family, which owned the Lion Grove Garden, Pei was captivated by the artistic conception of Suzhou gardens from a young age. The Lion Grove Garden, purchased by his great-uncle Pei Runsheng, became his first classroom for architectural aesthetics.

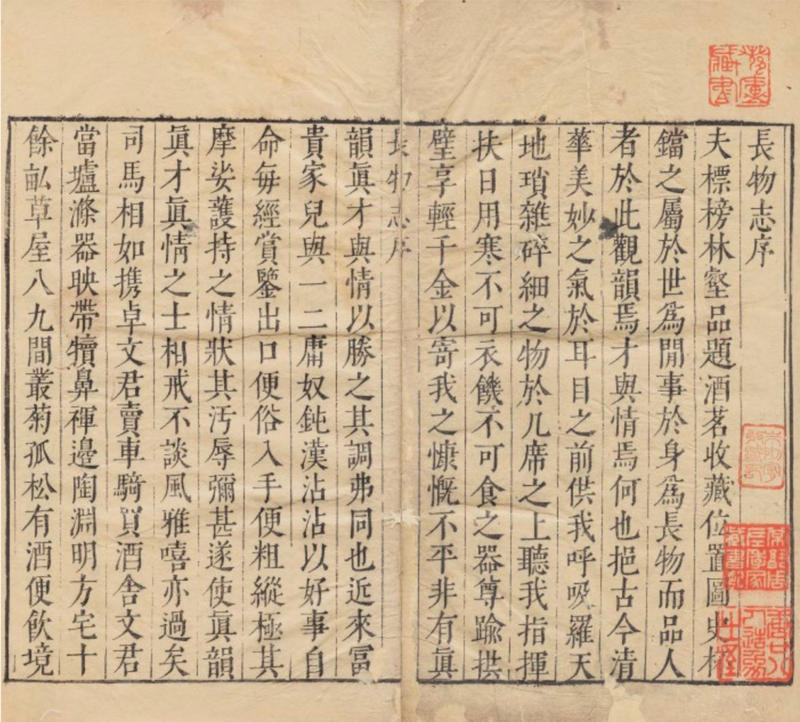

"I.M. Pei: Life as Architecture" will close at the Power Station of Art (PSA) in Shanghai on August 10th. This is the first comprehensive retrospective of Pei's work in mainland China. Meanwhile, in Suzhou, the Suzhou Museum's annual special exhibitions, "From the Humble Administrator's Garden to the Changwuzhi" and "From the Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden," recently opened, similarly demonstrating the influence of Suzhou garden aesthetics on Pei. The aesthetic philosophy of "preferring antiquity without time, preferring simplicity over artifice," as advocated by Ming Dynasty poet Wen Zhenheng's Changwuzhi, as well as the humanistic aesthetics of the Jiangnan region, permeated his spiritual DNA through the stone arrangement, water flow, and flower and tree arrangement of his family gardens.

I.M. Pei on a bridge at the Lion Grove Garden in Suzhou, circa 1930s. Courtesy of Peikoff & Partners.

Suzhou, an ancient city with 2,500 years of history, is renowned for its whitewashed walls, black tiles, and winding paths, known for its gardens. It was here that the world-renowned Chinese architect I.M. Pei (1917-2019) emerged, through the broadened horizons of Shanghai, and finally onto the world stage. Although he lived abroad for most of his life, he always insisted, "I have never forgotten China. I am Chinese."

Throughout I.M. Pei's century-long architectural career, the aesthetic essence of Suzhou gardens flowed like an undercurrent through his numerous classic works, from the Louvre Pyramid to the Suzhou Museum. Ming Dynasty scholar Wen Zhenheng's "Records of Superfluous Things," a quintessential example of Chinese garden aesthetics, championed concepts such as "the coexistence of dwellings and nature," "moss-covered stone steps," and "using walls as paper." These concepts found a modern translation and innovative continuity in Pei's architectural language. By analyzing the resonance between Pei's Suzhou cultural heritage and the aesthetic principles of "Records of Superfluous Things," we gain a glimpse into how an Eastern architect, using concrete and glass as his brush, wrote a contemporary chapter of Chinese civilization on the world's architectural landscape.

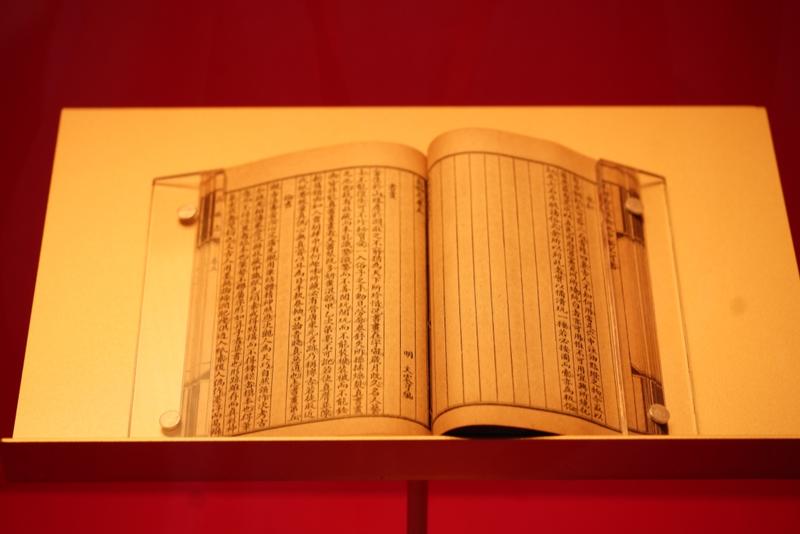

"From the Humble Administrator's Garden to the 'Superfluous Things' - The Aesthetic Life of Ming Dynasty Literati" special exhibition on display. 1915 Shanghai Civilization Bookstore lithographed copy, Suzhou Museum collection. (Photo by Thepaper.cn)

"From the Humble Administrator's Garden to Monet's Garden" exhibits Wen Zhenheng's "Records of Superfluous Things", a late Ming Dynasty edition from the collection of Ningbo Tianyi Pavilion Museum.

Childhood Enlightenment in Suzhou Gardens: I.M. Pei's Aesthetic Foundation

I.M. Pei's aesthetic roots are deeply rooted in the culture of Jiangnan. Born in Suzhou in 1917, he was born into the prominent Pei family—"a century-old family of distinction and prestige passed down through 15 generations." In the mid-Ming Dynasty, the Pei family's ancestor, Bei Lantang, settled in Suzhou to practice medicine and sell herbal medicine. By the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty, he had become one of Suzhou's four wealthiest people. I.M. Pei's branch, the Pei Zai'an, was renowned for its finance, while another branch, the Bei Runsheng, was known as the "King of Pigments." His Lion Grove, a garden he renovated, became a jewel of Suzhou gardens. It was this garden, designated by Emperor Qianlong as a guest during his six Jiangnan visits, that inspired I.M. Pei's architectural aesthetics.

When I.M. Pei was a teenager, he took a photo of himself in the Lion Grove Garden. This period of time became his spiritual home for the rest of his life.

The Lion Grove provided the young I.M. Pei with a living textbook on space, materiality, and nature. The discussion of the arrangement of water and rockery in Volume 3 of the Changwuzhi (Changwuzhi)—that "water and rockery can cleanse the mind and dispel worldly desires, bringing tranquility to the heart"—was embodied here. Playing among the rockery, Pei firsthand experienced the aesthetic appeal of Taihu stone's "thinness, wrinkles, porousness, and transparency." He felt the play of light and shadow among the pavilions and terraces, grasping Wen Zhenheng's spatial philosophy that "pavilions should be arranged to evoke the spirit of a wandering scholar." This immersive aesthetic education shaped his core understanding of architecture: "Creativity is the joint product of human ingenuity and nature."

Shanghai International Hotel

At the age of ten, I.M. Pei moved to Shanghai with his father. This modern city opened up a new perspective for him. He was struck by the modernity of the 24-story International Hotel, then the "tallest building in the Far East," and he would make a special trip to see it during his lunch break. He even drew a "detailed architectural blueprint" upon his return. He admitted, "In Shanghai, I glimpsed a future, or even the beginning of a future, that I hadn't seen in Suzhou."

The twin experiences of Shanghai and Suzhou planted the seeds of his connection—the Eastern wisdom of Suzhou gardens embodying the unity of nature and man, while the modern technological power of Shanghai's skyscrapers, seemingly contradictory, became a symbiotic blend in his later architectural practice.

Young I.M. Pei traveled to the United States to study architecture at MIT and Harvard. Though deeply influenced by Modernism, the genes of Suzhou gardens remained etched in his mind. His 1946 Harvard graduation project, a proposal for an art museum in Shanghai, already evoked garden imagery: a fusion of courtyards, flowing water, and geometric forms. This design felt like a prophecy, as decades later, at the age of 85, he designed the Suzhou Museum, showcasing similar visions in his homeland. As he put it, "The Suzhou gardens taught me the relationship between life and architecture"—a perception that transcends formal imitation, reaching directly into the essence of the relationship between space and humanity.

The Records of Superfluous Things and Jiangnan Aesthetics: The Oriental Code in Pei's Architecture

The Jiangnan humanistic aesthetic system constructed by Wen Zhenheng in "Changwuzhi" can be seen to have an influence and inheritance in I.M. Pei's architectural practice.

This inheritance is not a simple reproduction of overhanging eaves and brackets, but rather a distillation of traditional spatial philosophy into a modern architectural language, imbuing it with contemporary vitality. From the Beijing Xiangshan Hotel to the Miho Museum in Japan, and finally to the Suzhou Museum, three core principles permeate the entire project: a site selection and layout that blends with nature, a poetic expression of material textures, and a spatial narrative of flowing light and shadow—forms a dialogue across time and space that perfectly aligns with the concepts of "room" in Volume 1 and "water and stone" in Volume 3 of the "Changwuzhi."

The description of stairways in the "Changwuzhi" is insightful and poetic: "From three to ten steps, the higher the steps, the more ancient they are. They must be made of peeled stone; embroidered cushions or a few stems of grass and flowers should be planted inside... The inside of a double room should be higher than the outside, and hard stones covered with moss should be used to inlay them, so as to create a sense of rockery and ruggedness." This concept is reflected in many aspects of I.M. Pei's works:

For example, the Fragrant Hill Hotel (1982), I.M. Pei's first mainland China project after China's reform and opening-up policy, boldly rejected the then-popular imitations of antiques or purely Westernized styles. Taking advantage of the mountainous terrain, he adopted a duplex structure—the main building is elevated inside and outside, forming staggered terraces. The stone steps are constructed from local Fangshan rubble, their texture deliberately preserved, and pine and bamboo trees are planted in the gaps. As guests ascend, their view shifts with the height of the steps, recreating the spatial experience of "the beauty of the rocks and valleys" described in the book "Changwuzhi."

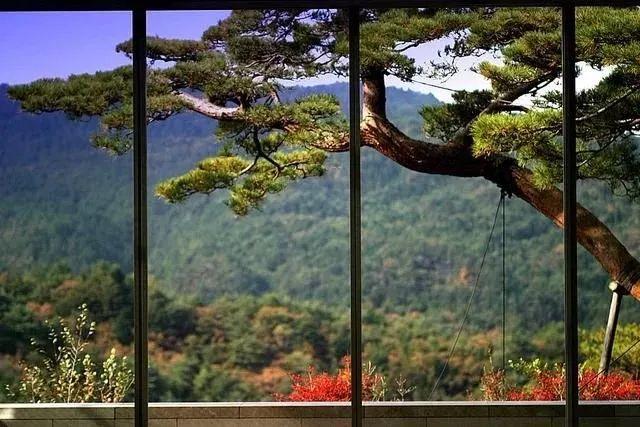

Miho Museum, Japan

Miho Museum, Japan

Another example is the Miho Museum in Japan (1997). Inspired by Tao Yuanming's "Peach Blossom Spring," I.M. Pei designed the entrance route as a ritual of discovery. Visitors first traverse a tunnel and then a suspension bridge to reach the main building. In this process, the gently ascending walkway becomes a modern version of "mossy steps"—stairs serve not only as a physical passage but also as a psychological medium of transition, filtering the hustle and bustle of the world into a tranquil Zen state. Wen Zhenheng's emphasis on "grass reflecting the steps and courtyard" is transformed into a dynamic canvas of maple and cherry blossoms, achieving a contemporary interpretation of "flourishing branches and leaves, reflecting the steps and walls."

Volume 3 of the "Changwuzhi" (Records of Superfluous Things) considers water and stone the soul of a garden: "Stones evoke antiquity, water evokes distance." I.M. Pei's modern interpretation of this concept is epitomized in the Suzhou Museum (2006): the north wall of the museum's main courtyard is transformed into a three-dimensional ink painting. Rejecting traditional rockery stacking techniques, Pei selected slices of stone from Mount Tai in Shandong, blasting them with a fire torch to reveal the depths and textures. These slabs, varying in thickness, are hung against a white wall, creating an abstract landscape: "the wall is paper, the stone is painting." This creation, inspired by Wen Zhenheng's admiration for the unique "waves" of Taihu stone, is realized within a minimalist, two-dimensional composition.

Interior of Suzhou Museum

The pool design breaks with the traditional practice of curved waterways in gardens, incorporating geometric forms. The water's surface precisely reflects the building's contours, juxtaposing solid and virtual forms, alluding to the Eastern philosophy of the interplay of reality and illusion. Even more profound are the fish swimming within the pond—during construction, I.M. Pei personally requested, "Please select more red fish," citing the Chinese idiom "Strive for excellence." This detail echoes the emphasis on fish viewing in Volume 3 of the Changwuzhi (Records of Superfluous Things): "It is advisable to keep golden carp, whose color dazzles against the clear water."

From Suzhou and Shanghai to the world: the global expression of oriental aesthetics

I.M. Pei's architectural practice, at its core, distilled the traditional Chinese spirit, exemplified by the Jiangnan humanistic aesthetic, into a universal spatial language, imbuing it with new life within the context of globalization. This transformation was not a mere patchwork of symbols, but rather a modern reorganization of light, geometry, and materials. A clear thread emerges throughout his oeuvre: from his early fusion of American Brutalism, to his mid-career geometric reconstruction of tradition, and ultimately, in his later years, a return to the harmonious realm of Eastern aesthetics—uninterrupted throughout by a supreme pursuit of "light," the very soul of architecture.

I.M. Pei once said, "I prefer to consider light as the primary element in architectural design. Without light, spatial form loses its vitality." This concept resonates across time and space with the control of light and shadow on window lattices and curtains in "Changwuzhi".

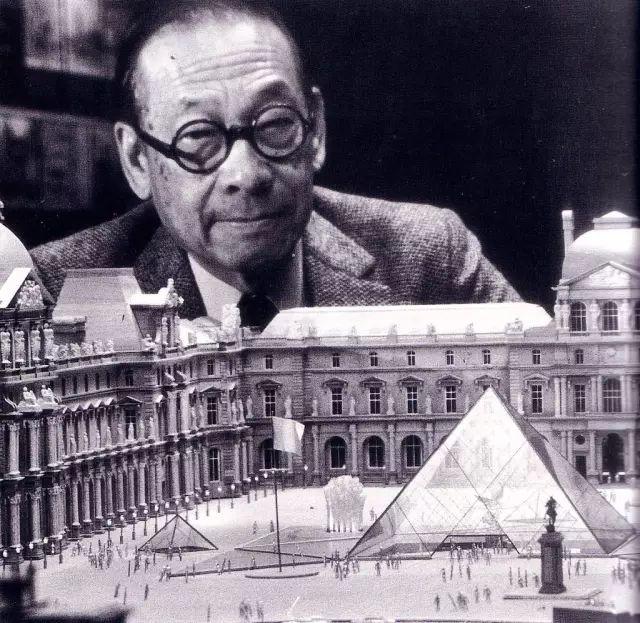

I.M. Pei in front of the Louvre Pyramid model

In the hands of I.M. Pei, the triangle was elevated from a simple engineering structure to an aesthetic medium connecting the East and the West.

Louvre Pyramid © Vincent Brière

Take the Louvre Pyramid, for example. Facing French skepticism, I.M. Pei employed a 51-degree pyramidal angle, echoing the Pyramids of Giza, while imbuing it with a modern, transparent quality. The glass curtain wall incorporates the Parisian sky into the building's envelope, revitalizing a classical symbol. When visitors gaze back from the underground lobby, the historic Louvre facade is framed by the pyramid's hypotenuse, achieving a global expression of "borrowed scenery."

©Koji Horiuchi

The book "Changwuzhi" (The Records of Superfluous Things) is extremely sensitive to the texture of materials: "Stone steps must be mossy, wood grain should appear natural, and paint colors should be limited to red and black." I.M. Pei incorporated this material poetics into modern building materials, such as his design for the National Center for Atmospheric Research in the United States. To integrate it into the Rocky Mountains, Pei conducted in-depth research on Native American rock dwelling sites. Ultimately, he used local sandstone ground into the concrete aggregate, giving the building a reddish-ochre color that matches the mountain.

National Center for Atmospheric Research

National Center for Atmospheric Research

In 2002, at the age of 85, I.M. Pei took on the design of the new Suzhou Museum, calling it "the greatest challenge of my life." This building, which he likened to his "dearest little daughter," embodies his lifelong wisdom and realizes a contemporary interpretation of the humanistic aesthetics of Jiangnan.

Suzhou Museum

The museum's main exhibition hall features a double-layered roof system: an upper layer of wood-grained metal panels filters glare, while a lower layer of frosted glass diffuses the light. Over time, the walls develop a rhythm of light and shade, reminiscent of an ink painting. I.M. Pei explained, "The light, modulated by the blackout strips, becomes more artistic...as if it were flowing."

Interior of Suzhou Museum

Today, as visitors walk through the exhibition hall, they can constantly glimpse the courtyard landscape through the diamond-shaped windows. Wen Zhenheng's ideal of "lofty and spacious pavilions and windows, open and narrow" is here deconstructed into geometrically framed scenes. The most striking aspect is the landscape garden, reminiscent of Song Dynasty paintings—white walls like paper, rocks like mountains, and the water like silk. At the opening ceremony, I.M. Pei said emotionally, "I left China 73 years ago, but my roots remain in Suzhou. This is my small contribution to my hometown."

Interior of Suzhou Museum

I.M. Pei once said, "The most beautiful architecture is that which transcends time; time will reveal all the answers." When the Suzhou Museum's stone landscape is reflected in a pool, when the Louvre's pyramid's glass curtain wall captures the drifting clouds of Paris, and when cherry blossoms drift across the geometric roof of the Miho Museum—we witness a "ferryman" transcending cultural barriers, transforming the aesthetic codes of Wen Zhenheng's "Changwuzhi" into an architectural language shared by all mankind.

His practice proves that the vitality of tradition lies not in rigid preservation but in creative transformation. From the idea of "the higher the steps, the more ancient" to the terraced courtyards of the Xiangshan Hotel, from "using the wall as paper" to the stone landscapes at the Suzhou Museum... I.M. Pei, using concrete, glass, and light as his brushstrokes, seems to have written a flowing "Record of Superfluous Things" in the history of world architecture. As he realized in his later years, "My architecture and I are like bamboo; no matter how strong the wind and rain, we only bend." This spirit, rooted in Suzhou gardens and Shanghai culture, has been the spiritual support that has sustained him through a century of trials and tribulations.