Today is the Great Heat, cicadas are chirping and the weather is hot and dry. There are three signs of the Great Heat: "Rotten grass turns into fireflies, the soil is moist and hot, and heavy rains occur from time to time." This is also the time when fruits are most abundant and best for cooling off.

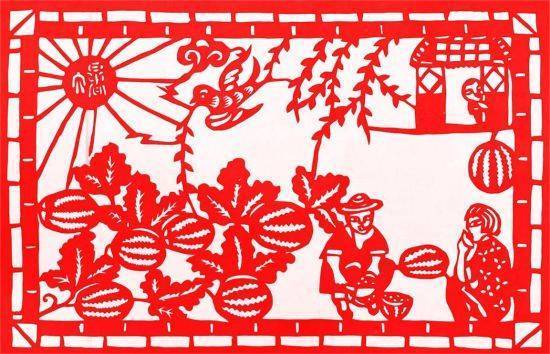

Melons are a common subject in Chinese folk art. In addition to depicting their shapes, more emphasis is placed on capturing their spirit. In addition to their ability to cool down and relieve summer heat, they also carry the auspicious meaning of "prosperity and prosperity" and a yearning for the beauty of the countryside. Folk artists of all generations have used melons as a medium, either by scissors, carving, or painting. It can be said that melons have been carrying the cultural memory of cooling down for thousands of years.

Watermelon Iconography from the Silk Road

Watermelon is a common summer food and is known as the "king of summer fruits". The early journey of watermelon to the East is itself a history of civilization exchange. Archaeological discoveries have confirmed that watermelon was introduced to northern China through the Silk Road around the Tang and Song dynasties.

The Shaanxi History Museum has a collection of Tang Sancai watermelons. The 13.5-cm-tall watermelon is full and round, with a curled stem that looks like it has dew marks. The glaze is verdant and dripping, and the glaze cracks spread like spider webs, as if it had just left the vine and was sealed in time. This watermelon was actually seized by the police in an operation to crack down on the resale of cultural relics. Although there was controversy, it was eventually determined to be a Tang Dynasty cultural relic, and it has become one of the earliest watermelon cultural relics currently available.

Tang Sancai watermelon

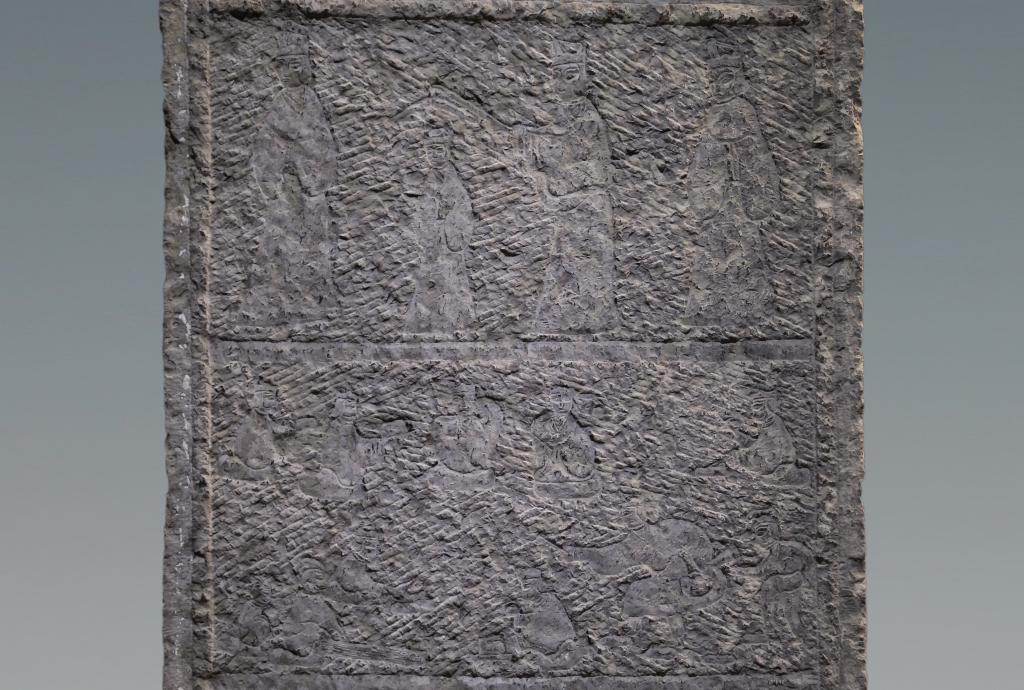

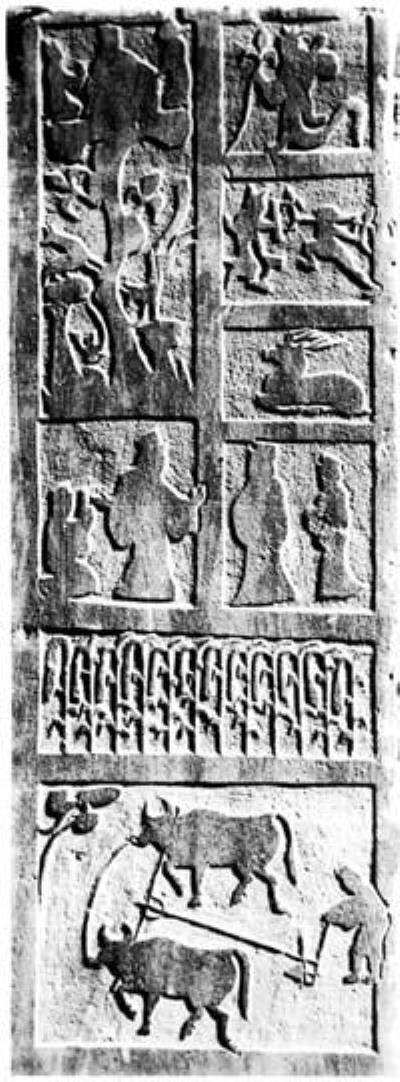

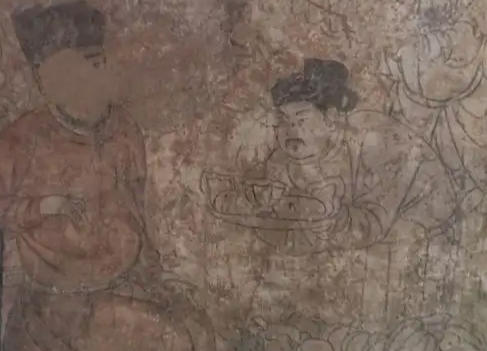

When Emperor Taizu of Liao, Yelü Abaoji, went on a western expedition to defeat the Uighurs, he brought watermelon seeds back to the heartland of Khitan. The watermelon seeds unearthed from the accumulation layer of the Liao Shangjing site in Chifeng, Inner Mongolia, and the clear image of watermelon in the murals of the No. 1 Liao Tomb at Yangshan, Aohan Banner, confirm the custom of "serving fruit plates with meals" at Liao nobles' banquets - watermelon had become a luxury at banquets at that time.

There are clear images of watermelons in the Khitan tomb murals

The Liao people's watermelon planting technology was full of wisdom. Hu Qiao's "Records of the Captured" records that the Khitan people "planted with cow dung covering the sheds", using the heat generated by the fermentation of cow dung to raise the ground temperature, and cultivated sweet and juicy watermelons during the short frost-free period in the northern frontier. This technology made watermelons widely planted in the northern Yan region. The watermelon images in the murals of the Liao Tomb in Zhaitang, Mentougou, Beijing, are the witness of the spread of watermelon culture to the south1.

After the Jin Dynasty conquered the Liao Dynasty, watermelons followed the Jurchens southward and entered the Yellow River Basin. When Fan Chengda witnessed the scene of "green vines lying on the soft sand in the frost, and eating watermelons everywhere" in Kaifeng, the watermelons that originally took root in the north had already multiplied throughout the Central Plains. In the Southern Song Dynasty, watermelons were brought to the south of the Yangtze River for extensive planting. Watermelons eventually completed the complete transmission chain from the Western Regions to the south of the Yangtze River, and also laid a material foundation for their diverse expressions in art.

In the Ming Dynasty, according to the "A Brief Account of the Scenery of the Imperial Capital", on the day of the Great Heat in the Ming Dynasty, the Forbidden City used the cellars to store winter ice, and red lacquer food boxes were filled with sliced watermelons to reward officials. The melons given by the emperor had to have green skins, and the melon stems were tied with red silk, symbolizing "serving the master with sincerity". In the "June Cooling" chapter of "Yongzheng's Twelve Months of Pleasure" in the Palace Museum, a palace maid holds a carved ice jar in her hand, and the watermelon inside is like a red jade soaked in snow, and the hollow "wan" pattern on the ice jar reveals a wisp of cold mist.

Watermelon lanterns carved with figures, insects and fish were popular in Yangzhou during the Qing Dynasty. Xu Zongyan praised them as "the vivid green and exquisite lanterns illuminate the snow-capped room, making one feel cool despite the heat."

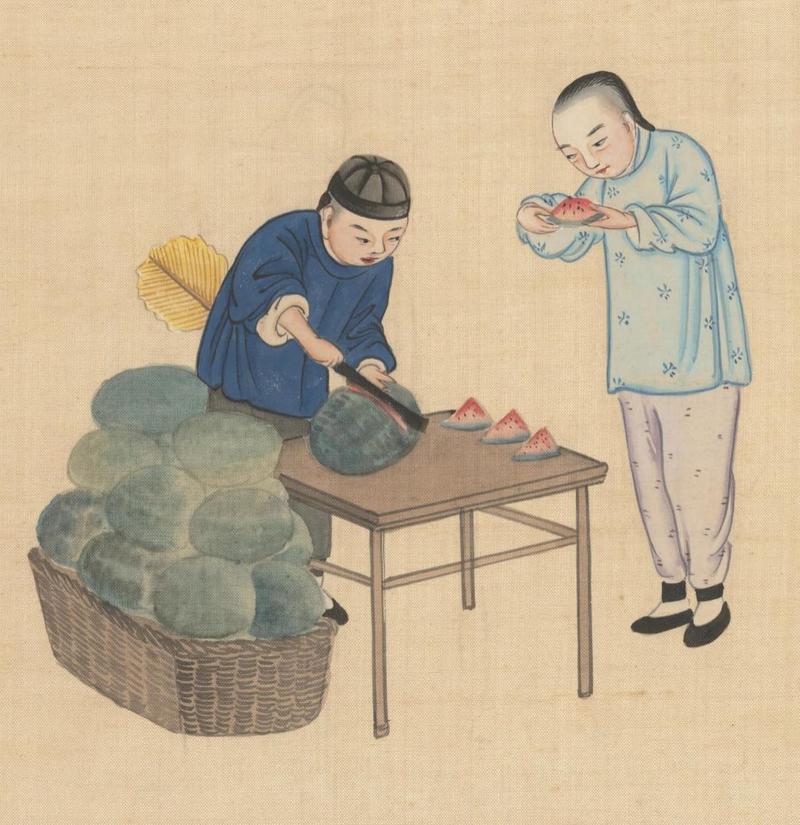

Watermelon stall Source: Illustrated Collection of Folk Life in the Qing Dynasty

The continuous succession of generations in the form of utensils

The use of melon-shaped patterns in folk crafts goes beyond the simple reproduction of physical images and becomes a cultural symbol that interweaves craftsmanship and meaning.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, melon-shaped objects in arts and crafts became increasingly sophisticated. The Tang Dynasty secret color porcelain melon-shaped vase unearthed from the underground palace of Famen Temple (collected by Famen Temple Museum) is made of Yue kiln celadon, with twelve concave edges equally dividing the vase body, and the glaze color is green and blue, like an uncut melon. Lu Yu's "The Classic of Tea" states that "Xing porcelain is like silver, and Yue porcelain is like jade." This vase is a perfect example of "like jade" - the edges flow like the meridians of a living melon under the light, confirming the artistic conception of the Tang poem "The wind and dew of the ninth autumn open the Yue kiln, and the green color of thousands of peaks is captured."

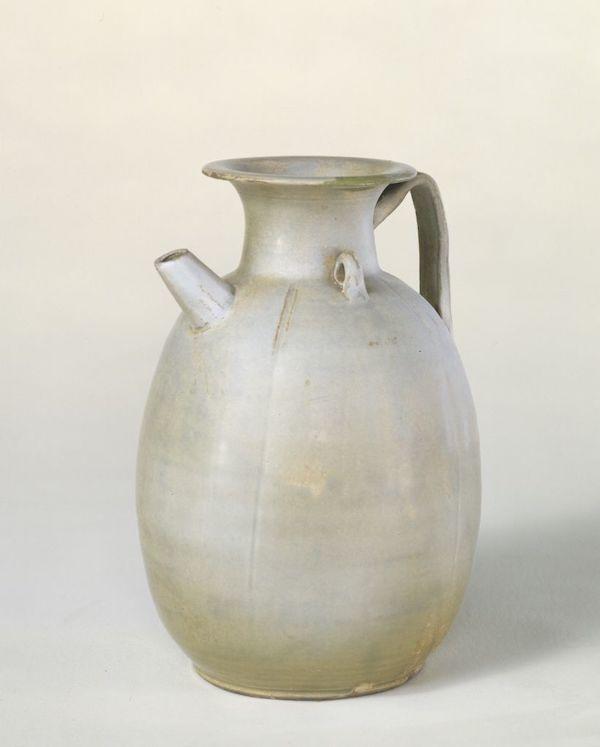

The Yue Kiln green-glazed melon-shaped pot from the late Tang Dynasty has a four-petal melon-shaped belly, and the inside and outside of the body and the inside of the foot are all covered with green glaze. The shape is round and full, and the glaze is moist. It is a representative work of Yue Kiln celadon in the late Tang Dynasty; the Ding Kiln melon-shaped pot with a handle from the Northern Song Dynasty has a pot body shaped like a melon, and the junction of the handle and the body is decorated with three melon leaves, making the handle look like a melon vine. The whole vessel is covered with ivory white glaze, with a firm and fine white body and a lustrous glaze. It can be called a fine product of the Ding Kiln of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Tang Dynasty Yue Kiln Green Glaze Melon-shaped Pot, Collection of the Palace Museum

Northern Song Dynasty Ding kiln melon-shaped handle pot, collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Craftsmen in the Ming and Qing dynasties took the melon shape to the extreme: the white jade melon-shaped pot from the Qianlong period of the Qing Dynasty (now in the collection of the Palace Museum) is carved all over in the shape of an autumn melon with branches and leaves. The melon stem is the lid button, the vine is the pot handle, and the leaf veins are as thin as gossamer threads. It can be called a masterpiece of "life-giving vines growing out of jade."

In jade, wood, bamboo and lacquerware, the shape of melon is mainly expressed in the form of imagery. The exquisite materials and exquisite craftsmanship reached their peak in the Qing Dynasty. For example, the bamboo yellow melon-shaped box of the Qing Dynasty is an oblong box with bamboo yellow pieces all over the surface. The branches and leaves that were originally carved are then pasted on the surface of the bamboo yellow pieces. The inner wall of the box is carved from boxwood. The branches on the cover protrude from one end and buckle on the edge of the box body. The entire box is almost covered with bamboo yellow pieces, but the branches on the cover reveal the original color of boxwood, making the light yellow of the wood and the brown yellow of the bamboo yellow pieces shine together. The inner wall of the box is covered with gold foil.

Early to mid-Qing Dynasty bamboo yellow melon-shaped box Wood and bamboo lacquerware Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Qing Dynasty carved bamboo melon-shaped box bamboo lacquerware, collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Another worth mentioning is the white jade melon-shaped washbasin in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. The wall of the vessel is surrounded by vines and melon leaves, with a small melon connected to it and two butterflies resting on the rim. Washbasins are stationery items and were more widely used in the Qing Dynasty. They have a variety of shapes and themes. Most of the works are exquisitely carved and have a high level of jade carving. This one is especially crystal clear, smooth and flawless, with a freshness and texture of a melon.

Qing Dynasty White Jade Melon-Shaped Washbasin Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

Summer scenery in intangible cultural heritage

Huang Zhijun of the Qing Dynasty wrote a poem: "It is good for cooling off and enjoying, and the skills are amazing. The watermelon is not only for eating, but also for carving patterns on the rind. Pinghu watermelon in Zhejiang was listed as a tribute to the royal family during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The "maple melon" introduced during the Republic of China became famous, and the local people's love for watermelon went beyond the tip of their tongues - the rind was carved into a lamp, and the candlelight reflected the patterns, which became a summer totem for the local land. The craftsman carved mountains, rivers, figures, flowers and birds on the entire watermelon rind, and built-in candles to light it. The candlelight penetrated the hair-like hollow lines on the rind, casting exquisite light and shadow in the night.

In Datong, Shanxi, paper-cutting artist Zhang Yuzhu carved a ten-kilogram watermelon into a flower-shaped ingot. The watermelon has a coiled dragon about to soar, Chang'e chasing the moon, and peonies blooming in layers.

In Longchuan, Yunnan, the inheritors of Dai fruit carving are also good at carving on the surface of watermelons. They have no drawings to refer to, and rely entirely on the coordination of their heart and hands. The bumps and curves where the blade passes are like living things, creating the "paper-cutting art on fruit."

Folk craftsmen carve watermelon rind

Ku Shulan's paper-cutting in Xunyi, Shaanxi, once pushed watermelon to a divine level: in the collage of layered colored paper, the red flesh in the center radiates like a sun, and eight birds with seeds in their mouths fly out from the jagged green skin, with the title "Birds hold seeds and the melon vines grow." The melon seeds are the symbol of life, and together with the birds, they form a metaphor for the harmony between heaven and earth.

In "Great Heat" by the inheritor of Shanzhou folk paper-cutting, "melon-eating people" sit in a circle, including melon farmers wearing straw hats and children sucking their fingers while watching. The watermelon cut in the center is presented using the yin-yang carving method - the positive red flesh is like leaping flames, while the negative melon skin is like calm black jade, which is a metaphor for the solar term dialectics of "extreme heat turns to coolness".

Folk paper-cut k "Great Heat"

From the banquet scenes in the Liao tomb murals to the melon lanterns in the Dai Water Splashing Festival, the melon-shaped patterns carry not only the sweetness of summer, but also an epic of life engraved on objects. The melon fragrance carved on stone and wood and wafting in the summer night has always been the simplest interpretation of a good life for the Chinese.