The fundamental flaw of the Kunlun Stone Carving is that its composition has no vertical and horizontal boundaries, and its calligraphy style does not match the solemnity, seriousness and elegance that it should have for the occasion it is used in. I am afraid it is a fake carving.

On June 8, 2025, Guangming Daily published an article on page 11 by Tong Tao, a researcher at the Institute of Archaeology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, titled "Verifying the Geographical Location of Ancient "Kunlun" - The Stone Carving of Qin Shihuang's Envoys Collecting Medicinal Herbs in Kunlun Discovered at the Source of the Yellow River in Qinghai", which caused an uproar. The focus of the debate was mainly on the authenticity of the Stone Carving of Qin Shihuang's Envoys Collecting Medicinal Herbs in Kunlun (hereinafter referred to as the "Kunlun Stone Carving").

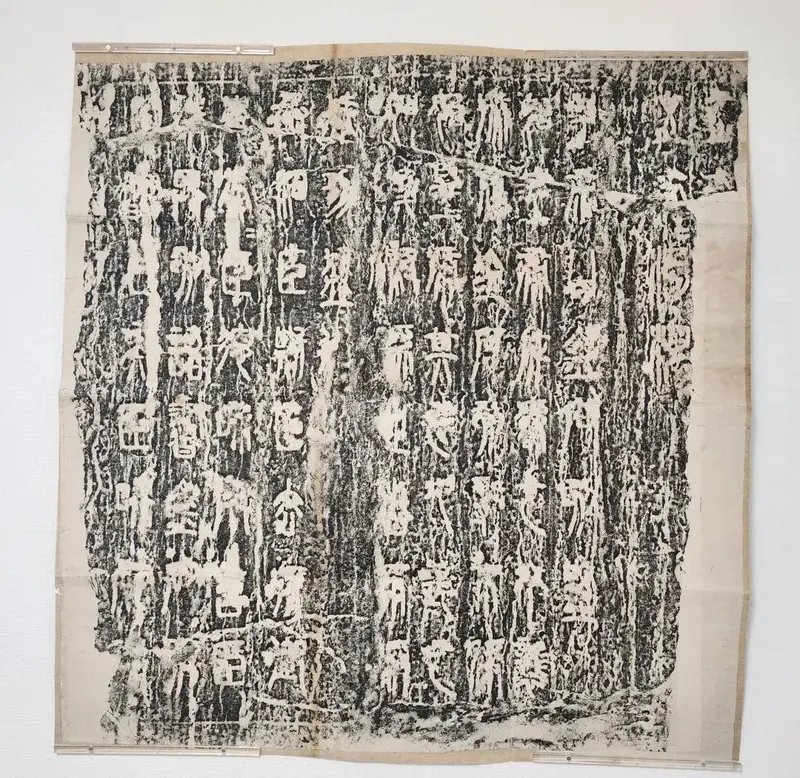

Kunlun Stone Carvings, illustration provided by Yihe.

Scholars have expressed their views from the perspectives of history, philology or customs. I will try to talk about my views on the authenticity of the Kunlun Stone Carvings from the perspective of calligraphy style. Needless to say, this article is negative.

1. The fundamental flaw: the writing style does not match the occasion

On June 12, 2025, Professor Liu Zhao, Director of the Center for Archaeological Documents and Ancient Chinese Characters Research at Fudan University, published an article titled “My Views on the Kunlun Stone Inscriptions” on the WeChat public account Ancient Chinese Characters Micro-Journal. He said: “Putting aside other things, looking at the text first, I think the text on the Kunlun Stone Inscriptions has obvious characteristics of the era, a unified style, and no flaws can be found.”[1] Mr. Liu Zhao is a great scholar whom I admire very much, but his research field is mainly in philology. Therefore, Mr. Liu may occasionally have small deviations in his judgment of calligraphy style, so I dare not hastily agree with his views.

I think this view is probably due to the confusion between the Qin Dynasty writing style in the sense of philology and the Qin Dynasty "stone-carved writing" style in the sense of calligraphy, or the confusion between the broad sense of the Qin Dynasty writing style (including stone-carved, imperial edicts, tiger-shaped seals, bamboo slips, seals, seals, weapons, etc.) and the narrow sense of the Qin Dynasty "stone-carved writing" style. In other words, even if the Kunlun Stone Carvings have no flaws in "character method" - the writing method in the sense of language - but in "writing style" - the shape style in the sense of calligraphy - it has exposed many flaws.

I understand that the "unified style" mentioned in the article should refer to the unified style of shape. In fact, the shape style of the Kunlun Stone Carvings is not unified, and it can even be said that it is very inconsistent. The reason for regarding the inconsistent style as unified may be the lack of calligraphy practice or the lack of calligraphy appreciation, but the most important reason may be the serious lack of attention paid to the close relationship between the Qin Dynasty's calligraphy style and the occasion, or the intentional or unintentional blindness to this close relationship - whether it is the forgers of the Kunlun Stone Carvings or the scholars who have a tentatively positive attitude towards the Kunlun Stone Carvings.

Xu Shen of the Eastern Han Dynasty wrote in "Shuowen Jiezi·Preface":

Since then, there have been eight styles of calligraphy in the Qin Dynasty: Dazhuan, Xiaozhuan, Kefu, Chongshu, Moyin, Shushu, Shushu, and Lishu. [2]

Among these eight scripts, except for the oldest large seal script and the newest official script, the remaining six, in terms of their "character method" in the sense of language, may not have fundamental differences in most of the characters. Since there is no fundamental difference, why did Xu Shen say "Since then, there have been eight scripts in Qin"? The answer lies in the "script style and occasion" emphasized in the title of this article. In other words, the eight scripts of Qin, especially the six in the middle, are mainly different in the "style" presented from the outside; from the inside, the difference is mainly in the "occasion" used.

What we know is that the Qin script used on the Yishan Stone Inscription, Taishan Stone Inscription, and Langya Stone Inscription is (two) "small seal script" because of the Qin's national decree of "writing with the same characters"; the Qin script used on the tiger seal is (three) "engraved characters"; the Qin script used on the seal is (five) "moyin"; the Qin script used on weapons is (seven) "shu script"; the Qin script used on bamboo slips is (eight) "official script" because it is "simplified and easy". As for (four) "worm script", "Shuowen Jiezi·Xu" talks about the "Xinmang Six Scripts" and says "the sixth is bird and worm script, which is used to write banners and letters", but Mr. Qi Gong believes that "the Qin worm script is the handwriting of large and small seal scripts, so there is no way to specifically mention its use." [3]

Why do different styles need to be used in different occasions? Mr. Qi Gong has a wonderful discussion in his "Draft on Ancient Fonts":

From the above, we can see that the Qin people used legal means to standardize the writing system. The styles of Qin writing were different for different purposes. For example, the writing styles of the stone tablets praising merits and the edicts on weights and measures were different. It can be seen that at that time, the writing styles of the characters were divided into different ranges according to their uses and could not be mixed. Therefore, there was an objective need to define the names of the characters. In other words, this was also a link in the means of "standardizing the writing system." [4]

In short, out of objective reality, the Qin government stipulated different levels of rigor in calligraphy styles according to the solemnity of the occasion. The basic logic is that the more solemn the occasion (or a certain link), the more rigorous the calligraphy style; the more casual the occasion (or a certain link), the simpler the calligraphy style.

Among all the occasions where the eight styles of Qin script are used, the most solemn and dignified one is probably stone carving.

The Qin people attached great importance to the stone carving. The "Records of the Grand Historian: The First Emperor of Qin" recorded the discussion of the Langya Stone when the marquises, the prime ministers, the ministers, and the five great officials were in the process of carving the stone. These discussions showed that the stone carving was a national event to "brighten the ancestral temple" and "praise the emperor's merits", and it was extremely solemn and serious.

... and discussed it with him at sea. He said: "In ancient times, the emperors had no more than a thousand miles of territory, and the princes each guarded their own fiefdoms. Sometimes they came to the emperor's throne, sometimes they did not, and sometimes they invaded and rioted, and destroyed each other without stopping. They still carved gold and stone to mark their own achievements. ... Now the emperor has unified the whole country and divided it into counties, and the world is at peace. He has made the ancestral temple glorious, embodied the Way and practiced virtue, and is honored with the title of Dacheng. All the ministers have praised the emperor's merits and virtues and carved them on gold and stone to serve as a memorial." [5]

When “the emperors of ancient times had a territory of no more than a thousand miles”, they still “carved on gold and stone to mark themselves”. Now that the emperor has unified the world, wouldn’t it be “bright and glorious for the ancestral temple”? Therefore, the current “carving on gold and stone to mark the classics” is naturally very solemn and serious. This solemnity and seriousness cannot be overemphasized.

In order to emphasize the close relationship between calligraphy style and occasion, this article does not call this style of calligraphy by its original name - "small seal script", but focuses on its occasion - "carved stone calligraphy" (or it can also be called "stone calligraphy" or "carved stone style", to avoid ambiguity, let's call it "carved stone calligraphy").

The “stone-carved writings” of the Qin Dynasty refer to the eight types of stone-carved writing styles recorded in the Records of the Grand Historian. In the past, it was said that there were seven types of stone-carved writings during the Qin Dynasty. According to the Records of the Grand Historian[6], there were at least eight types of stone-carved writings during the Qin Dynasty. In order of the time when they were written, they are:

1. "Yishan Inscription" (28th year, 219 BC, erected by Qin Shihuang. The original stone has been lost. The existing stele was re-engraved in 993)

2. "Taishan Stone Inscription" (28th year, 219 BC, Qin Shihuang established it. There are two types of broken stones with 10 characters in total, carved in 209 BC during the reign of Qin Ershi)

3. The Qian Zhifu Stone Inscription (28th year, 219 BC, when Qin Shi Huang came to power; [7] the original stone has been lost. To distinguish it from the commonly known Zhifu Stone Inscription, the word “Qian” is added to the name here)

4. Langya Stone Inscription (28th year, 219 BC, when Qin Shihuang was established, and 209 BC, when Qin Ershi was inaugurated, 87 characters are now preserved)

5. Zhifu Stone Inscription (29th year, 218 BC, established by Qin Shihuang, the original stone has been lost)

6. The Stone Inscription at the East Pavilion of Zhifu, also known as the Stone Inscription at Zhifu (III) (29th year, 218 BC, erected by Qin Shihuang, the original stone has been lost)

7. Jieshi Inscription (32nd year, 215 BC, erected by Qin Shihuang, the original stone has been lost)

8. Kuaiji Stone Inscription (37th year, 210 BC, erected by Qin Shihuang, the original stone has been lost. The existing stele was re-engraved in 1792)

There are four types of Qin Dynasty stone inscriptions, including those engraved in later generations, that can be seen today: the Taishan Stone Inscription, the Langya Stone Inscription, the Yishan Stone Inscription, and the Kuaiji Stone Inscription.

Figure 1-1 Rubbings of the Taishan Stone Inscription

Figure 1-2 Rubbings of the Taishan Stone Inscription

There are two pieces of stone inscriptions on Mount Tai, one with 4 characters and the other with 6, for a total of 10 characters. They were carved in 209 BC during the reign of Emperor Qin II and are now stored in the Taian Dai Temple. There are also two Northern Song Dynasty rubbings of the Taishan Stone inscriptions, one with 165 characters and the other with 53 characters, both of which are now stored in Japan.

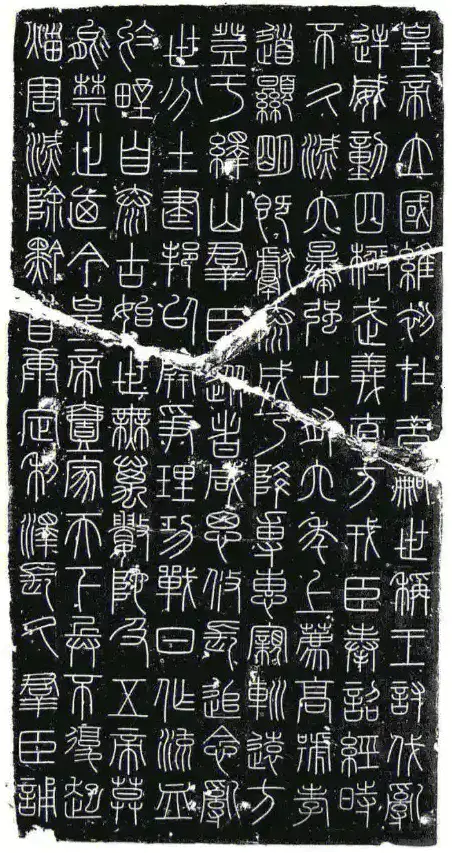

Figure 2-1 Langya Stone Inscription

Figure 2-2 Langya Stone Inscription

The Langya Stone Inscription, now in the collection of the National Museum of China, contains 87 characters in 13 lines. The first two lines were carved in 219 BC, and the last 11 lines were added during the reign of Qin II.

Figure 3 The Yishan Stone Inscription, reprinted in 993

The existing inscription on Mount Yi was re-carved by Zheng Wenbao in 993 (the fourth year of Chunhua in the Northern Song Dynasty) based on Xu Xuan's copy. The stone is now in the Xi'an Forest of Steles Museum. Because it was re-carved in the Song Dynasty about 1,200 years later, the strokes of the inscription on Mount Yi are very smooth and the characters are a bit stiff, but it is still an important reference for the authentic inscriptions of the Qin Dynasty.

The existing version of the Kuaiji Stone Inscription was re-engraved by Liu Zheng in 1792 (the 57th year of Emperor Qianlong's reign in the Qing Dynasty) based on the re-engraving by Shentu Yu in 1341 (the first year of Emperor Zhizheng's reign in the Yuan Dynasty) collected by Qian Yong. It is now in the Stele Gallery of Dayu Mausoleum in Shaoxing. The style of the Kuaiji Stone Inscription re-engraved in 1792 is similar to that of the Yishan Stone Inscription re-engraved in 993, and can also be used as a reference for the Qin Stone Inscription.

These four Qin Dynasty stone inscriptions all have a solemn, dignified and elegant style. Their layout, both vertically and horizontally, has a relatively strict grid order. In layman's terms, there are grids in both the vertical and horizontal directions. Don't underestimate the existence of this vertical and horizontal grid. When facing national events such as the stone inscriptions of "Zhaoming Zongmiao" and "Song of the Emperor's Merits", this vertical and horizontal grid is a symbol of national dignity, order and legitimacy. On the contrary, without this vertical and horizontal grid, I am afraid that its legitimacy and authenticity cannot be fundamentally proved.

The biggest flaw of the Kunlun Stone Carvings is that they have no vertical or horizontal grids. Not only are the characters of the Kunlun Stone Carvings not uniform in size horizontally, but even vertically, there are cases where two or three lines on the left and right are interlaced. For example, lines 4 and 5 (将方□/采药昆), lines 7, 8, and 9 (二十六年三月/己卯车到/此翳□). It can be said that the vertical and horizontal order of the Kunlun Stone Carvings is very loose.

Therefore, the fundamental flaw of the Kunlun Stone Carvings is that its writing style does not match the solemnity, seriousness and elegance that it should have in the occasions where it was used. Therefore, we have sufficient reason to doubt its authenticity. Whether intentionally or unintentionally, if we ignore this fundamental flaw and only examine whether the writing method of the text is correct and whether it has the characteristics of the Qin Dynasty, I am afraid that we are missing the point.

2. Specific flaws: Mixing multiple styles of calligraphy from different eras

If we believe that the Kunlun Stone Carvings are fake, we may ask, can we point out the flaws more specifically? Below we briefly cite a few examples and make a brief analysis.

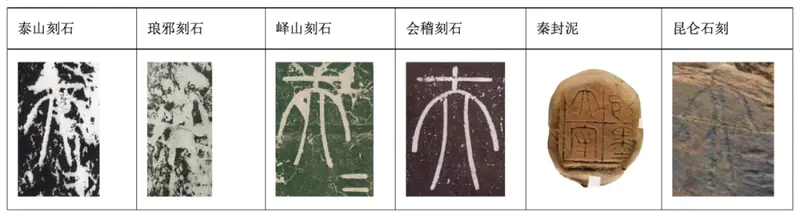

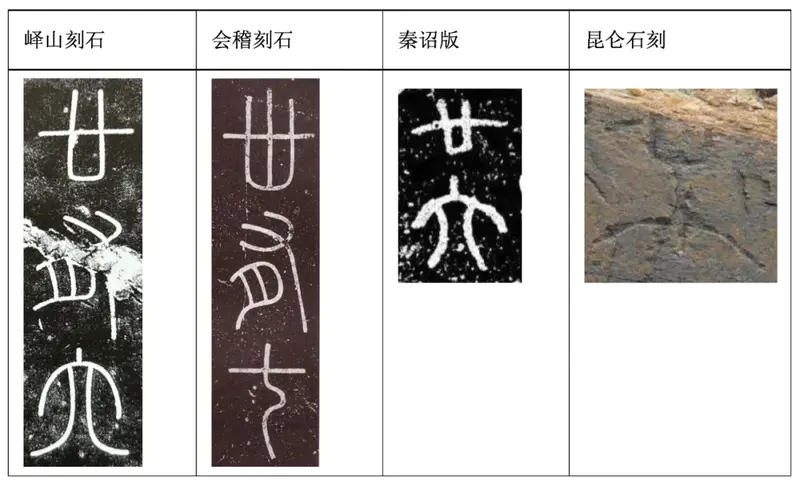

1. Emperor: Seems to have mixed the Qin edict version

Table 1

The "Emperor" in the Kunlun Stone Carving is similar to the Qin Dynasty carving, but the last horizontal stroke is more curved, which has never appeared in the Qin Dynasty carving. The "Emperor" character seems to be mixed with the Qin Dynasty edict, but the "Emperor" character suddenly shrinks, making the "Emperor" in the Kunlun Stone Carving even more sloppy than the sloppy Qin edict.

When I was about to finish this article, I read Mr. Liu Shaogang’s article “Questions about the Kunlun Stone Inscription” on June 16, 2025, which talked about the evidence put forward by Mr. Dong Shan, namely, the writing method of the character “皇” in the “改名方” of the Liye Qin Bamboo Slips: “After the unification of characters, the horizontal stroke of the character 皇 in the shape of ‘白’ is not connected to the border, but is a short horizontal stroke suspended in the middle.” Mr. Liu concluded, “In fact, this one opinion put forward by Mr. Dong Shan alone is enough to prove that the ‘Kunlun Stone Inscription’ is a modern forgery.”[8]

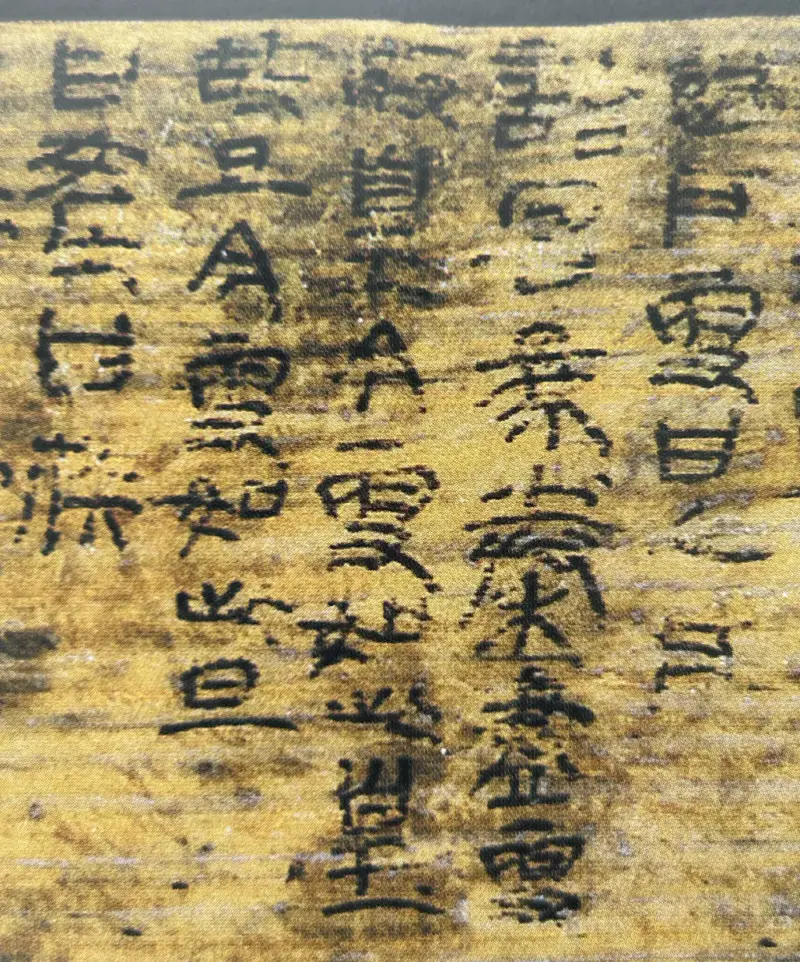

Figure 4-1 Liye Qin Bamboo Slips "Recipe for Changing Names"

Figure 4-2 Liye Qin Bamboo Slips "Recipe for Changing Names"

What is worth noting here is the curvature of the last horizontal stroke of the character "皇" in the "改名方" of the Liye Qin Bamboo Slips. Imagine if the forger of the Kunlun Stone Carving had also suspended the horizontal stroke in the "白" part of the character 皇, would it be possible to prove its authenticity? The answer is that it is still appropriate to identify from the perspective of whether the style and the occasion are consistent. In other words, although the Liye Qin Bamboo Slips "改名方" is undoubtedly true, the obvious curvature of the last horizontal stroke of the character 皇 in the "改名方" does not prove that the larger curvature of the last horizontal stroke of the character 皇 in the Kunlun Stone Carving is reasonable. Because the Qin stone book and the Qin bamboo slips were used in different occasions, their styles cannot be compared.

In short, the word "Emperor" on the Kunlun Stone seems to be a mixture of the Qin Stone and the Qin edict.

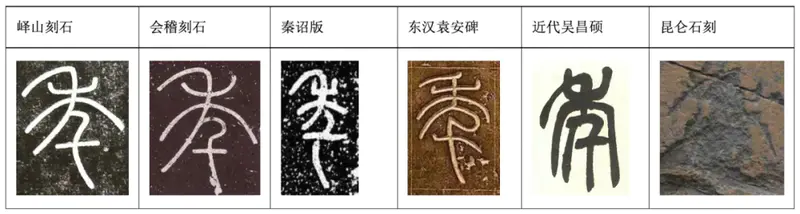

2. Doctor: Not as good as Qin seal mud

Table 2

The word "doctor" on the Kunlun Stone Carving has two vertical strokes in the middle, which makes it look cramped, dry and hesitant. It is not only far from the open, full and firm style of the Qin Dynasty stone inscriptions, but is even inferior to the Qin Dynasty seal mud, such as the "Jimo Taishou" seal mud.

3. 26 (37): Seems to be mixed with the Qin edict version

Table 3

The two characters "二十六" in the Kunlun Stone Carving seem to be mixed from the Qin Stone Carving and the Qin Imperial Edict. Some people interpret it as "卅七", which is probably not correct, because the arc of the horizontal stroke of the character "七" seems impossible to be so exaggerated.

4. Year: seems to be mixed with modern writing

Table 4

The oblique stroke on the upper left of the character "年" in the Kunlun Stone Carving intersects with the short vertical stroke on the upper left. This situation has never appeared in Qin Dynasty stone carvings, and is very rare even in Han Dynasty writings. This situation is common in recent seal scripts, such as the works of Wu Changshuo (1844-1927). Therefore, it is probably a mixture of modern writing methods.

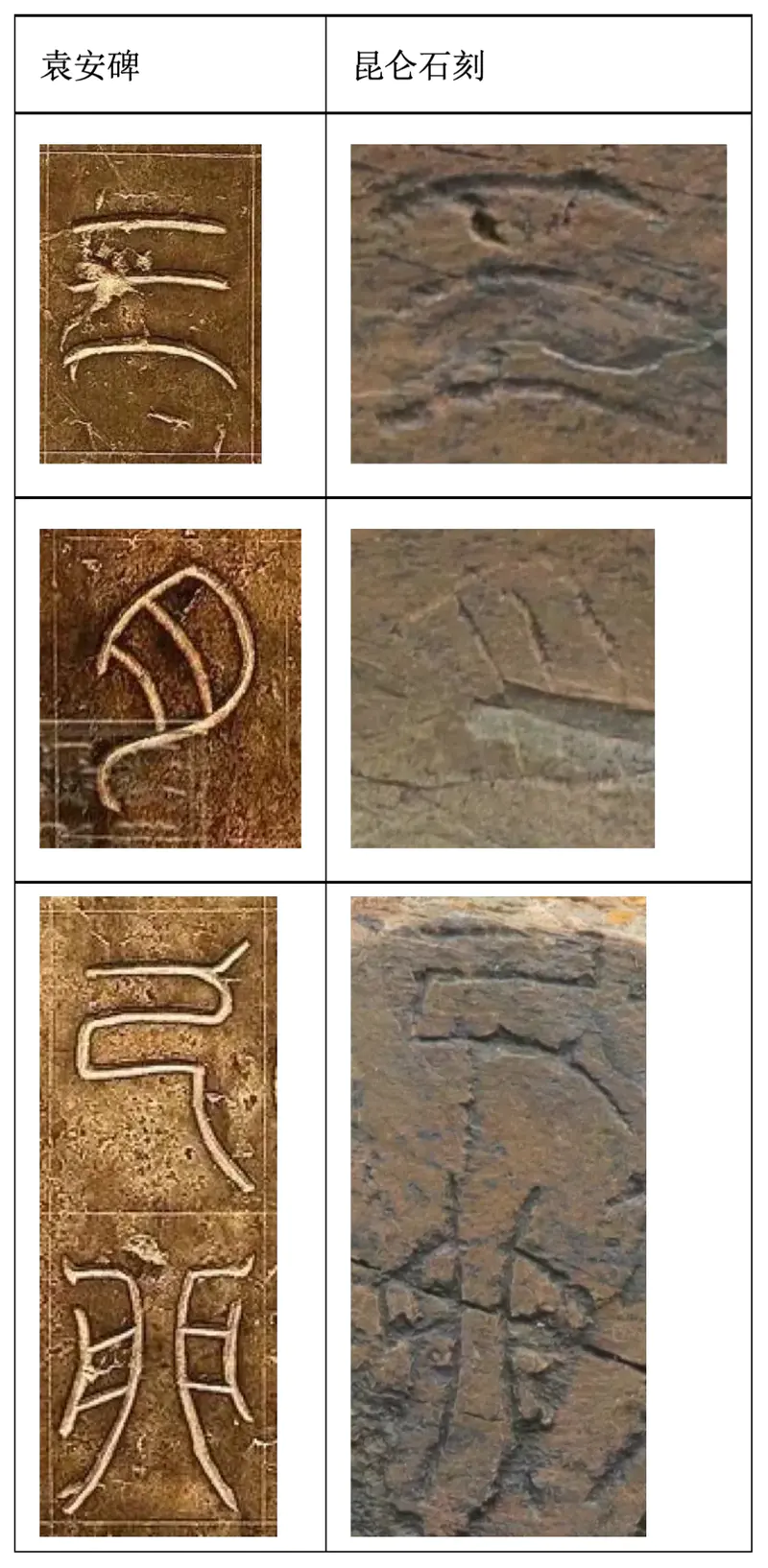

5. March, Jimao: Seems to be mixed with the Eastern Han Dynasty "Yuan An Stele"

Table 5

The "March" and "Jimao" in the Kunlun Stone Carvings seem to be mixed with the calligraphy style of the "Yuan An Stele" (erected 105 years later) in the Eastern Han Dynasty. Relatively speaking, the turning points of the Qin Dynasty stone carvings are round, while the turning points of the Han Dynasty seal scripts are square. As we all know, writing the turning points of seal scripts in a square manner, that is, using the official script to write seal scripts, was a great contribution of Deng Shiru in the Qing Dynasty - learning from the Han Dynasty. Since the "Yuan An Stele" is a very meticulous work, even in the Eastern Han Dynasty, its turning points still have the ancient style of roundness. Why is the turning point of the "Ji" character in the Kunlun Stone Carvings of the Qin Dynasty so square?

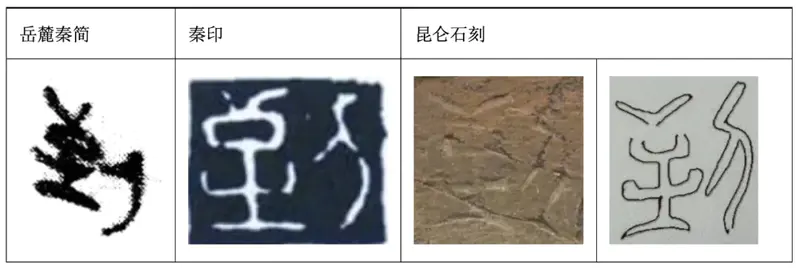

6. Dao: seems to be mixed with Qin seal

Table 6

The second-to-last horizontal stroke on the left side of the character “到” in the Kunlun Stone Carving has no vertical strokes on the left and right ends in normal writing (such as the Yuelu Qin Bamboo Slips). Only in the “Moyin” style of the eight styles of Qin calligraphy, vertical strokes are added at both ends to fill the blanks. Therefore, it seems that the Qin seal is mixed here, that is, the “Moyin” style of the eight styles of Qin calligraphy is mixed.

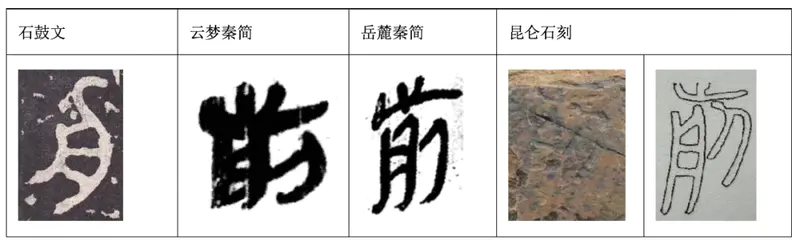

7. Front: seems to be a mixture of Qin bamboo slips and large seal characters

Table 7

The first horizontal stroke of the character "舟" in the Kunlun Stone Carving is tilted upward, which is a typical way of writing in the "大篆" style of the eight styles of Qin Dynasty calligraphy. That is, the forger seems to have mixed the style of Qin bamboo slips. Even in the stone inscriptions of the Spring and Autumn Period, the first horizontal stroke of "舟" would not be so tilted.

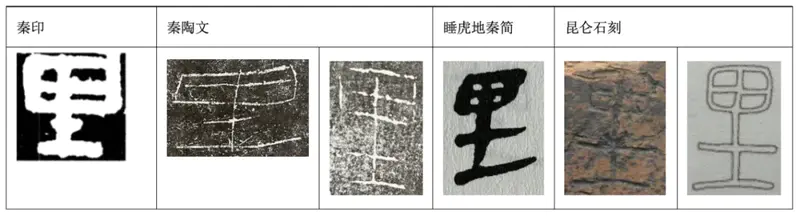

8. Li: seems to be mixed with Qin bamboo slips

Table 8

The "里" character carved in Kunlun Stone has a very small "田" shape at the top, while the two horizontal lines at the bottom occupy a very large space. It is different from the Qin seals and Qin pottery inscriptions, and seems to have mixed the style of the Qin bamboo slips found at Shuihudi.

The original interpretation is "one hundred and fifty li". "One hundred" is probably a combination of "two hundred". Therefore, "two hundred and fifty li" is also likely a foreshadowing, a joke, or a prank by the forger.

In summary, the credible stone inscriptions of the Qin Dynasty all have a solemn, dignified and elegant style. Their layout, both vertically and horizontally, has a relatively strict grid order. When facing national events such as the stone inscriptions of "Zhaoming Zongmiao" and "Song of the Emperor's Merits", this vertical and horizontal grid is a symbol of national dignity, order and legitimacy.

The fundamental flaw of the Kunlun Stone Carving is that its composition has no vertical and horizontal boundaries, and its writing style does not match the solemnity, seriousness and elegance that it should have in the occasion where it is used. It is probably a fake carving that mixes Qin stone carvings, Qin edicts, Qin bamboo slips, Qin seals, the Eastern Han Dynasty "Yuan An Stele" and even modern seal scripts, or even a prank by the forger.

June 18, 2025

(The author is a calligraphy researcher. From 1999 to 2012, he obtained a bachelor's, master's and doctoral degree in calligraphy from the Central Academy of Fine Arts. He founded and taught calligraphy at Shandong University of the Arts for many years. He is currently an associate professor at a university in Beijing.)