Jane Austen (1775-1817) was a British novelist. She lived only 41 years old, published her first work at the age of 35, and had only 6 representative works in her life. In Maugham's words, her life can be summed up in "a few words". However, today, Austen has already become a super literary idol, and her works have been translated into dozens of languages and adapted into film and television works.

This year marks the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen's birth. The Morgan Library and Museum in New York recently held a special exhibition "Lively Mind", presenting iconic artifacts from Austen's former residence and artworks, manuscripts, books, etc. collected by cultural institutions such as the Morgan Library, revealing Jane's personal charm and how she entered the literary world.

Visitors to the new exhibition “A Living Mind: Jane Austen at 250” at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York will find it filled with interesting objects related to the author. These include her turquoise and gold ring, briefly owned by American pop star Kelly Clarkson, items on loan from Austen’s home in Hampshire, England: a hand-sewn simulated silk coat that Austen is said to have worn, and a replica of the humble desk where she wrote her six extraordinary novels, masterpieces of early 19th-century English literature.

Miniature portrait of Jane Austen. Anonymous, circa 1870-1900

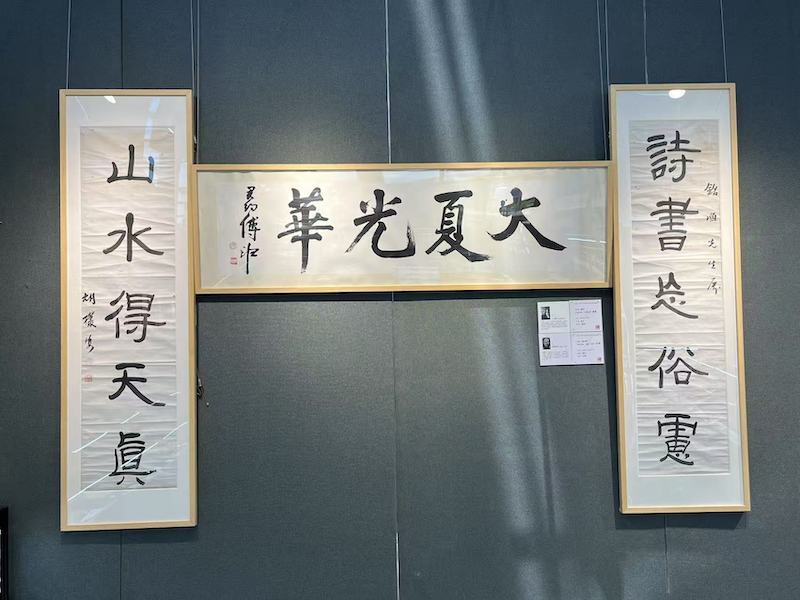

Exhibition site

But this exhibition, marking the 250th anniversary of Austen's birth, convincingly focuses on her work: what she did, and how and why she did it. It effectively counters the image of Austen as a retired spinster who wrote as a pastime, tracing her creative trajectory using letters, manuscripts and other materials, and illustrating how seriously she took her writing career.

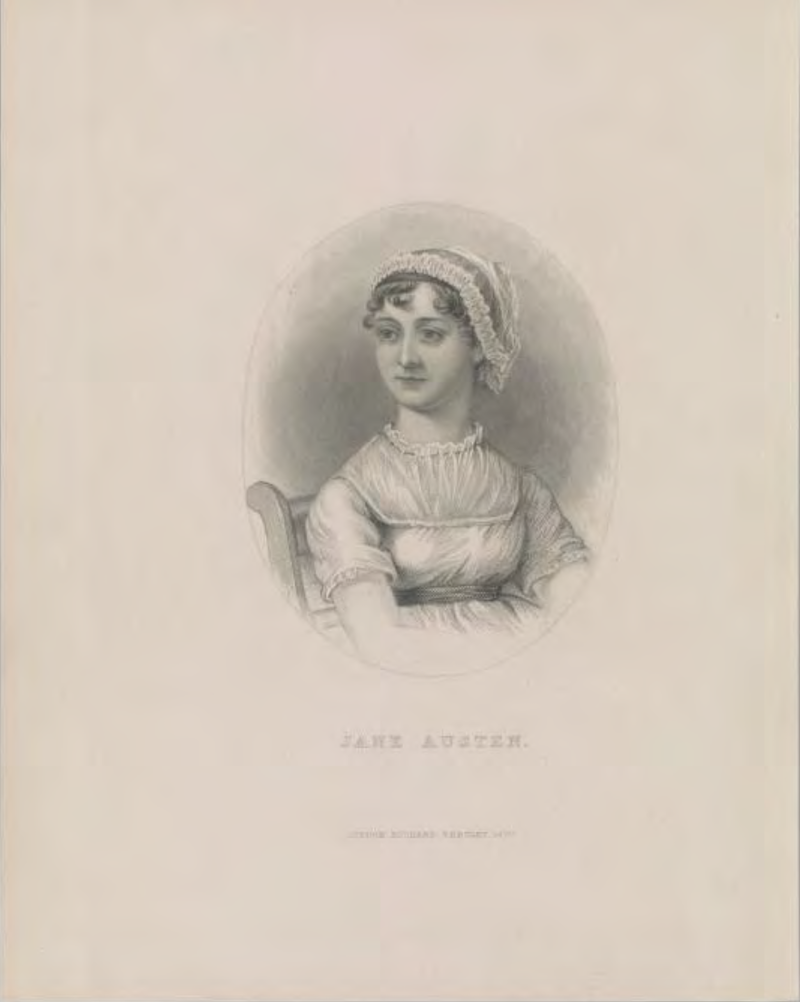

Portrait of Jane Austen, steel engraving

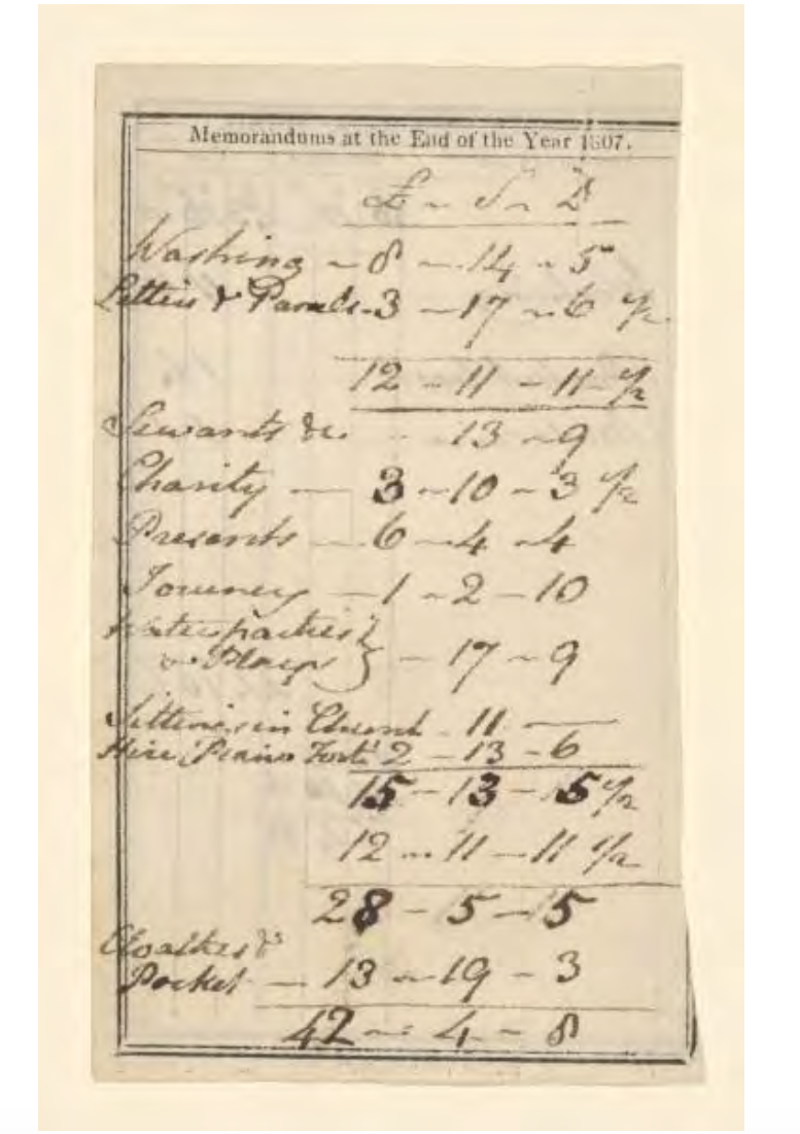

Jane Austen's personal account memorandum, December 1807

It’s thrilling to see the evidence. For example, on a small scrap of paper, Austen lists “the proceeds of my novels.” This is one of three books she wrote, transcribing some of her teenage work. It’s evidence that as a little girl, she was putting her imagination into fiction and thinking about how it would work. Here’s a heavily revised page from an unfinished novel, covered with crossed-out lines and altered words. The novel was published posthumously as The Watsons. Here Austen shows that she was both a writer and a diligent rewriter.

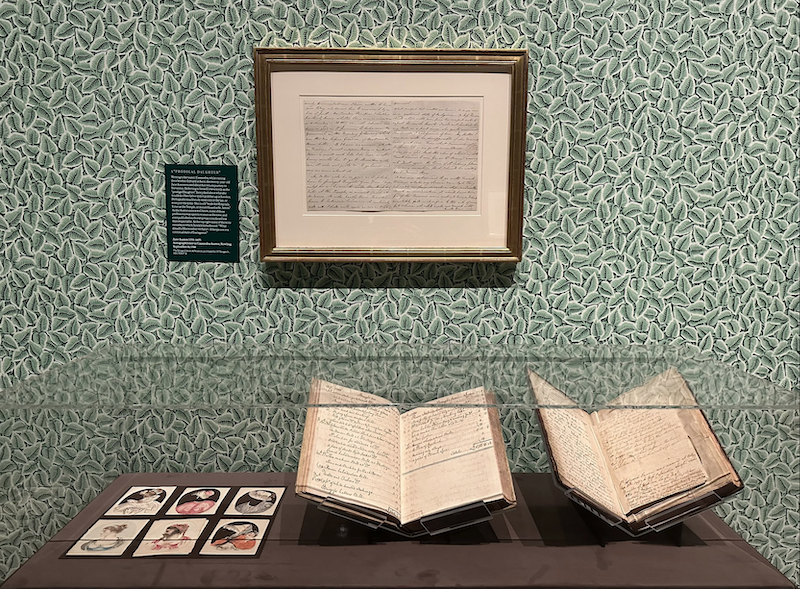

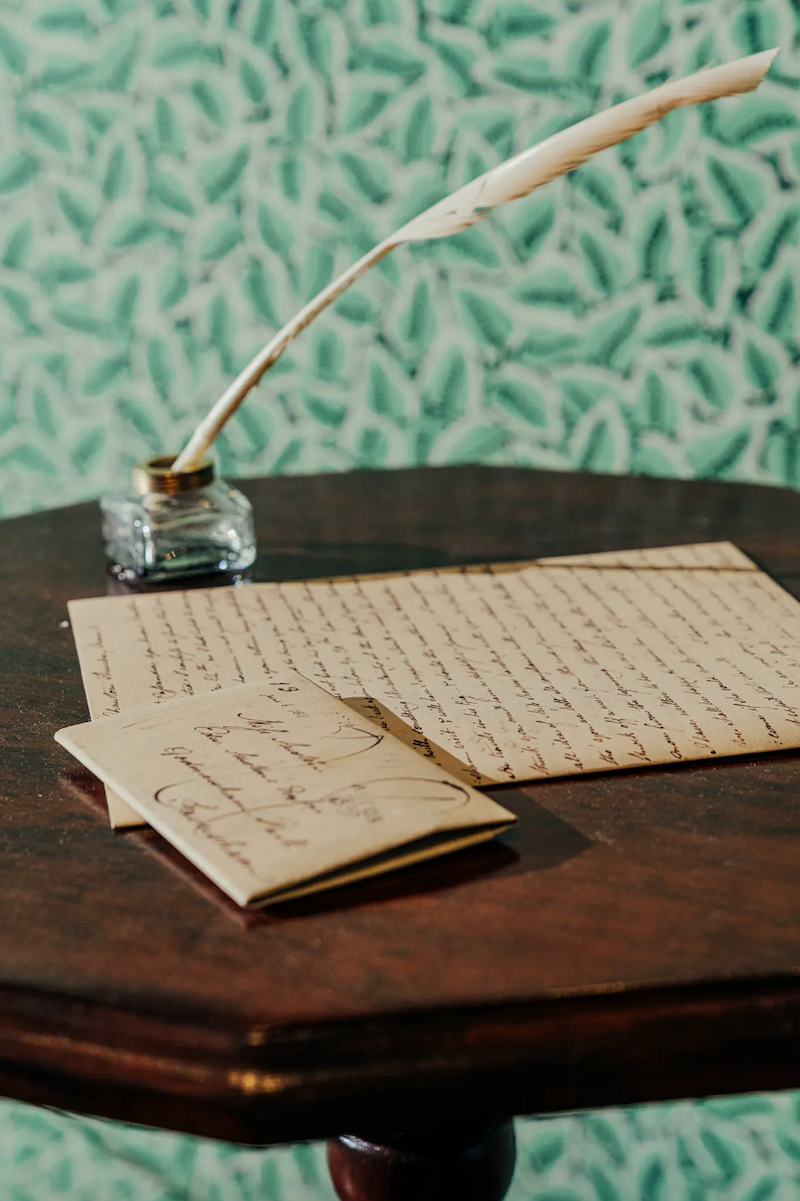

Austen's desk (replica), with green chardonnay leaf-patterned wallpaper, evokes the dining room where she wrote

Jane Austen's gold and turquoise ring, on loan from Austen House in Hampshire, England

“We wanted to bring this to the table because after her death, her family had spread some of the myths about her, that she didn’t care about fame, money, or hard work,” said Juliette Wells, a professor of literary studies at the Gotcher School and co-curator of the exhibition with Dale Stinchcomb. “The exhibition also shows how Austen’s family supported her writing and explores how Austen published novels that were popular with the public at a time when women were generally not allowed to be writers,” said Stinchcomb, the Morgan Museum’s curator of literary and historical manuscripts. The exhibition is one of many Austen-themed events marking the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth and the 50th anniversary of the bequest of Austen manuscripts to the Morgan Library by one of the country’s greatest Austen collectors, Alberta H. Burke of Baltimore.

Exhibition site

Austen lived a quiet life, away from the literary world, and died in 1817 at the age of 41. She did not live to see her own great success. The four books she published during her lifetime were Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park, and Emma. However, she signed her name with "a lady".

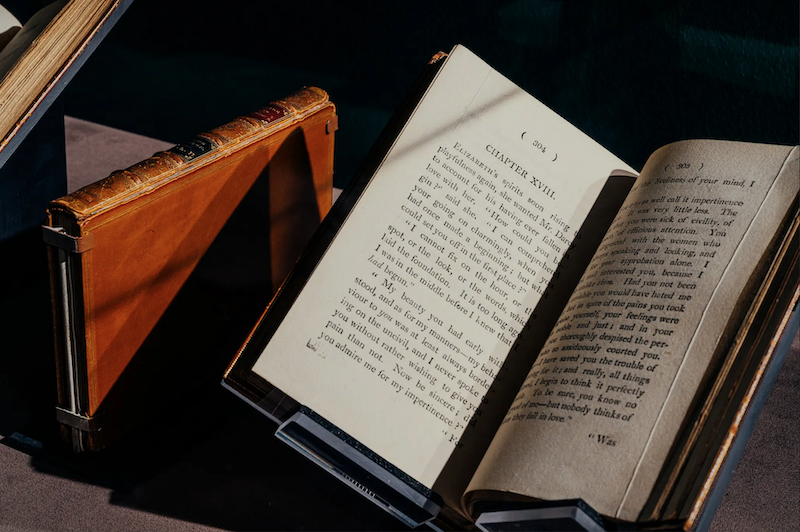

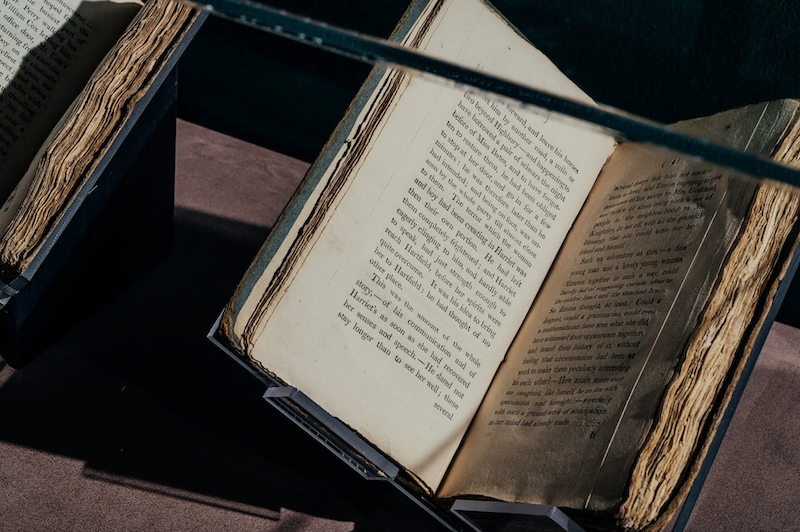

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, three volumes, printed by T. Egerton, 1813

Many documents in the exhibition hall show that she and her family fought to get her work published and cared deeply about what readers thought of it. One delightful document lists the various relatives and friends who wrote "What they thought of Emma" at the beginning of the book. The readers' comments come entirely from the author's close circle, like a 19th-century Goodreads entry.

Thus, Austen's sister-in-law "liked and admired Emma very much", although she preferred Pride and Prejudice. We also see that Austen's niece Fanny Knight called the protagonist's love partner Mr. Knightley "very pleasant", but "could not stand Emma herself". A lady named Miss Bigg thought that there were "too many scenes of Mr. Elton and H. Smith" in the book.

A page from Jane Austen's novel Emma. It lists what Austen's friends and family said about Emma at the top of the page.

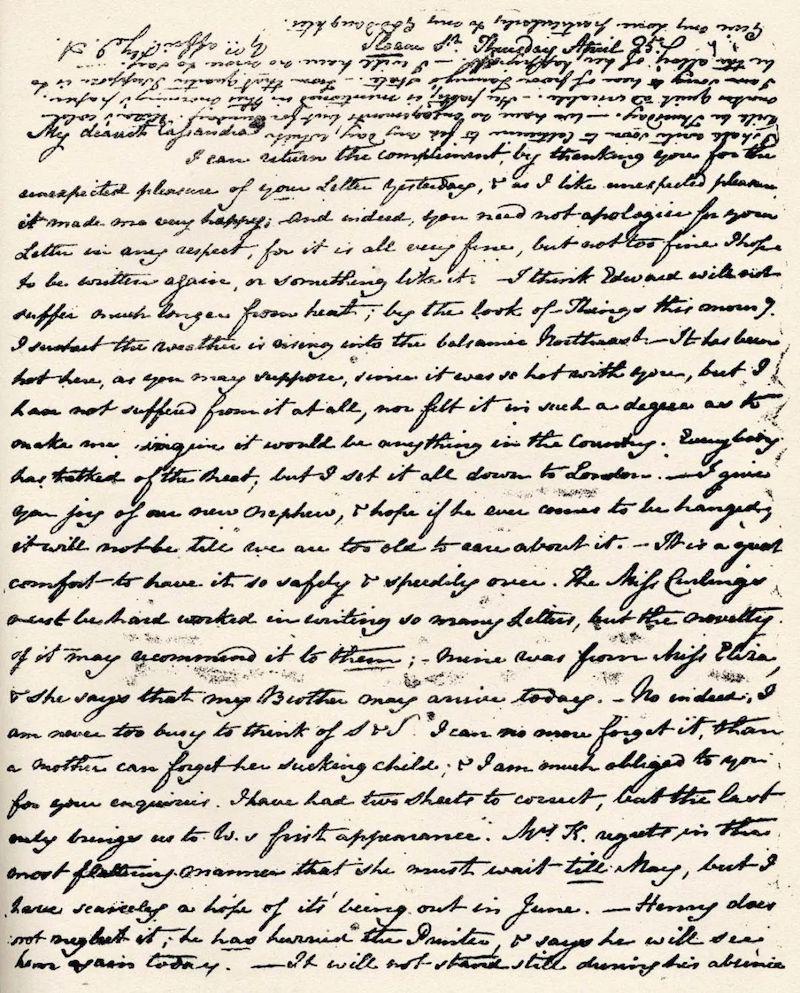

Austen was a talented letter writer. After her death, her sister Cassandra is said to have destroyed many of her letters. This may have been to protect her sister's privacy, but no one is sure. Fewer than 200 of Austen's letters exist, 51 of which are owned by the Morgan Library and Museum, many of which were purchased by JP Morgan himself in the early 20th century.

Her letters are full of life, gossip, sarcasm, and wit. “We have a dreadful hot weather here!” she wrote to Cassandra in 1796. “It keeps one in a state of inelegance.” In another letter, she expressed admiration for an acquaintance, saying that “she adores Camilla, and drinks her tea without cream.” This refers to the novels of Fanny Burney, whose work Austen greatly admired.

Silhouettes of Reverend George Austen (Jane Austen's father) and Cassandra Leigh Austen (Jane Austen's sister), early 19th century

The exhibition also shows how Austen’s own bold and forthright sensibility was reflected in her novels. Each of the first editions of her six novels contains a passage that either deals with the concept of the “lively mind” or with one of the author’s key ideas. In Northanger Abbey, for example, Austen addresses the reader directly in a famous passage, offering a powerful defence of the novel and declaring that it “provides a wider and more natural pleasure” than other kinds of books.

In Persuasion, Anne Elliot responds heartily when an acquaintance reminds her that the "inconstancy" of women is a perennial literary theme. This is because "men have an advantage over us in telling our own stories," Anne replies. "They are highly educated; the pen is always in their hands." This is a good argument for Austen's reason for writing.

Jane Austen's silk gown, decorated with a golden oak leaf pattern, shows her stylish temperament

Illustration of a fashionable morning dress from Jane Austen's time

Illustration for Sense and Sensibility, 1898-1899

Another notable piece of content is a video showing how Austen's silk coat was made and how one would walk around in it. The inscription on Austen's tombstone in Winchester Cathedral praises the writer's "charity, devotion, faith and purity" and "her extraordinary intellect" but makes no mention of any of her writings. There's also a playful letter she wrote to her eight-year-old niece, Cathy, with every word spelled backwards.

Jane Austen's handwritten letter to her sister Cassandra

Also on display are four of the six extant first editions of Emma published in the United States. One of them belonged to Jeremiah Smith of New Hampshire, an Austen fan who served as governor and chief judge of the state at various times. He had a habit of changing the content of the book with his pen. Interestingly, he changed "imaginist" (a word invented by Austen to describe Emma's imagination) to "imaginast" (another fake word).

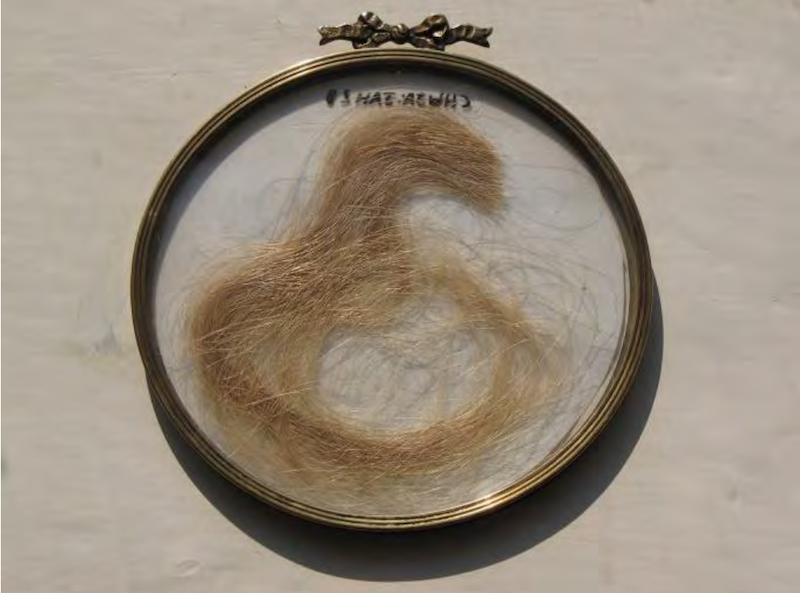

A lock of Jane Austen's hair, 1817, on loan from Jane Austen House, Chawton

J. Austen: after an original family portrait, engraving, 1873

It’s a delight to see Austen emerge from these documents. It’s also touching to see how much she was loved — Cassandra was Austen’s closest person during her life and death. “She was the sunshine of my life, deepening every joy, soothing every sorrow,” she wrote to Fanny a few days after Jane’s death. “I feel as if I have lost a part of myself.”

The exhibition will run until September 14th.