What is the basis for "observing qi" and "interpreting paintings" in the appraisal of ancient calligraphy and paintings? How can images prove history? What is the relationship between image research and appraisal?

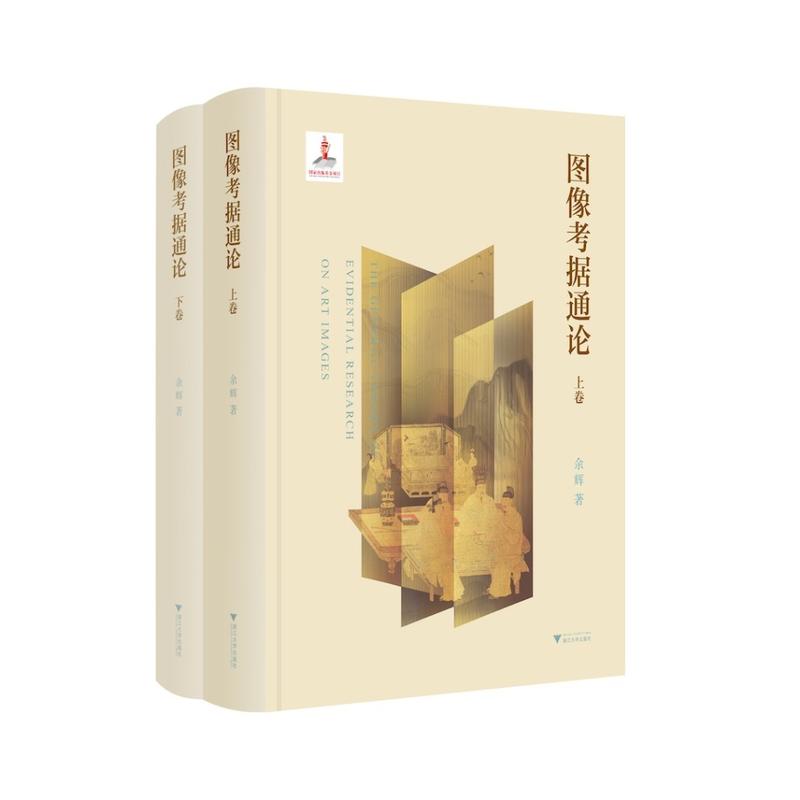

"Image research originates from academic appraisal in calligraphy and painting authentication, and is a follow-up exploration after authenticity authentication. Without scientific authentication as a foundation, image research is like a tree without roots. Image research, like text research, is inseparable from the authentication of materials. " Yu Hui, a researcher at the Palace Museum, said this in his new book "General Theory of Image Research."

The book was recently published by Zhejiang University Press, and includes his theories on image textual research. The Paper|Ancient Art specially selected and published his excerpts.

Image textual research comes from academic identification in calligraphy and painting authentication, and is a further exploration after authenticity identification. Without scientific authentication as a foundation, image textual research is like a tree without roots. Image textual research, like textual research, is inseparable from the identification of materials. Like authentication work, image textual research is a very practical thinking activity, but the radius of this activity has been further expanded. Authentication is to visually identify the relationship (author, collector) and physical properties (painting and mounting materials, tools, preservation conditions, etc.) of the image. Image textual research is to conduct in-depth exploration and extension of knowledge in the fields of humanities and social sciences and natural sciences in the form of textual research after completing the authentication procedure, and covers the research scope of authentication. The process of image textual research is actually a review of the authentication results, including drawing conclusions based on empirical authentication methods. The two form a very close complementary relationship.

(I) “Observing the Qi”, “Interpreting the Painting” and Identification

When paintings and calligraphy became collectibles, markets, interests, counterfeits, and appraisals followed one after another. Appraisals helped to make paintings and calligraphy collectibles. This logical chain was gradually established during the Eastern Jin Dynasty and the Southern Dynasties. When paintings entered the field of collection, there were two industries: counterfeiting and appraisal. In particular, literati got involved in appraisal research and counterfeiting activities, and even secretly merged them into one industry, making the appraisal of paintings and calligraphy more complicated. As Shen Defu said, "There have always been many counterfeits of antiques, especially in Wuzhong. All literati use them to make a living. Recently, the predecessors are as clean as Zhang Boqi (Zhang Fengyi), but they can't help but make a living from this. As for Wang Bogu (Wang Xideng), he used this as a strategy." Such "antiques" have left countless mysteries for future generations.

Just as there are originals, rubbings, copies, and forgeries of ancient books, there are also authentic, copied, and forgeries of ancient calligraphy and paintings. There have been many activities of copying ancient calligraphy and paintings in the courts and the public throughout the dynasties. In the Tang and Song dynasties, there were large-scale activities organized by the court to copy the calligraphy and paintings of the ancients, and many copies were carefully made. At that time, they were for the purpose of extending the life of the originals and studying. Due to human and natural factors in history, the scroll paintings handed down from the Eastern Jin Dynasty have disappeared, and there are few scroll paintings from the Tang Dynasty. Experts and scholars of the calligraphy and painting appraisal team of the State Administration of Cultural Heritage have basically identified the collections of cultural and museum institutions, re-verified the appraisal conclusions of the ancients and the royal family, and distinguished the copies from the originals, and the authentic from the forgeries. This was an important topic in the study of ancient calligraphy and painting in the mid-to-late 20th century.

The Tang, Song, late Ming and prosperous Qing dynasties were the four peaks of calligraphy and painting collection and appraisal. Each peak saw the exploration of appraisal theories and methods. There are roughly two methods for authenticating ancient paintings: "observing the aura" and "interpreting the painting".

(1) About “Looking at the Qi”

The identification method based on experience is commonly known as "looking at the spirit". It mainly relies on the experience accumulated over the years and the ability to be familiar with the identification object. For example, through a large number of readings to be familiar with the works of a certain painter in different periods and the language habits and characteristics of the works of related schools and times (composition, brushwork, modeling) and "spirits" such as seals, the law of its artistic formation and evolution can be found out, and combined with the inscriptions and seals in the paintings, a set of empirical "looking at the spirit" scales can be formed to determine its authenticity. For example, when facing Wu Changshuo's plums and rocks, Qi Baishi's shrimps and crabs, etc., the "spirits" in these paintings have no direct connection with the timeliness of social history and humanities, and generally do not directly constitute the humanistic elements of image textual research, and can only make empirical judgments on their authenticity. Therefore, the traditional empirical "looking at the aura" is an indispensable identification method. Its teaching is quite limited, and the main way is word of mouth between teachers and students. Some of them are perceptual experiences that are difficult to express in words. Learners need to go through a long period of practice and perception before they can understand and gradually form a style identification spectrum belonging to personal perceptual experience. It is difficult to deal with ancient paintings outside this spectrum. The identification conclusions formed by scholars appear in the form of a few words in inscriptions or notes, and it is difficult to elaborate on their principles.

The biggest limitation of the "Aura-Watching" method is that it is difficult to solve the problem of identifying paintings before the Yuan Dynasty. The identification method of early paintings is different from that of paintings from the Ming and Qing Dynasties to modern times. There are not many early paintings left, and few of them are signed or stamped by the authors. In addition, a small number of paintings without signatures or seals are judged to be works of an anonymous author in a certain dynasty, and most of them are attributed to a famous artist. What's more, counterfeiters in the Ming and Qing dynasties mixed figure paintings of the current dynasty with early ancient paintings. Therefore, it is difficult for modern people to solve the problem of identifying early paintings using the "Aura-Watching" method.

(2) On “Interpreting Paintings”

After solving the authenticity of the brush and ink style, when conducting in-depth exploration of its ideological connotation, creative motivation, artistic influence and other aspects, it is difficult to carry out follow-up research based on the perceptual brush and ink experience and style identification. This requires a rational textual research method, drawing on relevant disciplines to uncover everything behind the image. This is another identification method based on textual research images. Since the Southern Dynasties, it has been commonly known as "Jiehua", which is similar to the academic identification of modern people, that is, according to the era characteristics of social history and humanities reflected in the images of events, objects, etc. in the painting, as well as the relevant recorded collection history, to determine its author and era. When faced with an extremely limited number of early ancient paintings, it is difficult to fully recognize the style of a painter in different periods, and most of them are borrowed from some paintings of the same period. Image textual research comes from the early academic identification of "Jiehua", which is organized into an identification method and research means that can be taught in addition to "Wangqi". This process is to collect all available texts and images, and follow the systematic procedures of image textual research, namely evidence collection, verification, analysis, judgment, verification, etc., to obtain a series of relevant research results, and finally present them in the form of investigation reports or academic papers. The entire textual research process does not exclude the method of "looking at qi", and its premise is to accept the verified "looking at qi" conclusions.

"Observing the Qi" based on sensory experience and "interpreting paintings" based on rational textual research are two different identification methods that complement each other and are irreplaceable. The two have the same but different social purposes and functions. The purpose of empirical identification is to gain economic benefits in the calligraphy and painting market. In modern society, it also adds a social function, namely, providing basic information services for museum collections, involving eras, authors, schools, records, and collections. Academic identification has more social functions, such as conducting follow-up special in-depth research on museum displays, education, and publications, and expanding to cooperative research with universities and research institutes.

The resurgence of textual criticism in the Qing Dynasty, especially the formation of the Qianlong and Jiaqing schools, greatly nourished the theory and methods of textual criticism. For example, textual criticism, version identification, and version source system verification formed an academic chain. The development of textual criticism in the Qing Dynasty provided reference experience for image criticism, especially that textual criticism was no longer limited to the authenticity of the version era. Image criticism is following this path to explore and solve problems such as historical facts in images.

After nearly a hundred years of social development, the connotation and extension of calligraphy and painting authentication are no longer limited to the authenticity recognition of the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China. Both the needs of the general public and the wishes of researchers are far from being satisfied with this. It is necessary to further explore the relationship between the author's thoughts, life, motives and the themes and contents of the paintings, as well as other related paintings. Even when faced with counterfeits, they must be given due analysis and positioning.

(3) Finding the “secret door” with problem awareness

Identifying the authenticity of ancient paintings is the beginning of textual research on images, just as knowing all the leopard spots does not mean knowing the leopard. Theoretically speaking, identifying the surface features of an object is by no means the end of knowledge. The key is that in some ancient paintings with a relatively deep cultural heritage, only the painters of that era often have the cognitive methods and means of expression of that era to depict things. In such images, the consistency between the content and the era is unquestionable, which is the entrance to identifying its age. Researchers should do everything possible to get close to that era and try to be as if they were there in person, so as to get close to the cognitive methods and results of the time, and discover all the truths of that era, so as to strive to interpret the image content in place without overstepping, and moderate without excessive.

If you want to know the images in an ancient painting with rich content, complex background and long history, you may need to prepare many keys to open multiple doors of cognition, or even accumulate the knowledge of several generations to open layers of unknown doors. It is easier to open the visible door and the visible lock, and the most difficult is to open the hidden locks on some invisible doors. Their hidden existence will make us mistake the beginning of cognition for the end. The proposition of textual research must be a combination of subjective and objective. The problem consciousness in the mind of the textual researcher is the key to finding the hidden door, which is mostly hidden in the details. For example, the hidden door of the scroll "Double Screen Chess Picture" by Zhou Wenju of the Southern Tang Dynasty (a copy of the Northern Song Dynasty) is arranged in the order of succession to the throne of "brother succeeds brother". Logically, the cognition of this painting seems to be complete, but there is another hidden door in the hidden door, that is, the picture is a copy of the Northern Song Dynasty. The Northern Song Dynasty court copied the picture carefully in order to preserve the historical evidence of "brother succeeds brother". Emperor Taizong Zhao Guangyi was the first "brother succeeds brother" in the Northern Song Dynasty! Here, any emotional factors such as confidence, satisfaction or contemptuous attitude will make you forget the existence of the secret door.

Zhou Wenju of the Southern Tang Dynasty (a copy from the Northern Song Dynasty), "Double Screen Chess Game", in the collection of the Palace Museum

2. The objective existence of the “post-identification era”

Since the Chinese Ancient Calligraphy and Painting Authentication Group organized by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage twice in the 1960s and 1980s successfully completed the historic task of authenticating the authenticity of more than 100,000 calligraphy and paintings, the research on ancient calligraphy and painting authentication can be said to have entered the "post-authentication era", that is, the stage of deepening and expansion of ancient authentication science. In this "post-authentication era", the experts and scholars of the two authentication groups and their disciples continued to conduct a large amount of textual research on the calligraphy and paintings that had been authenticated.

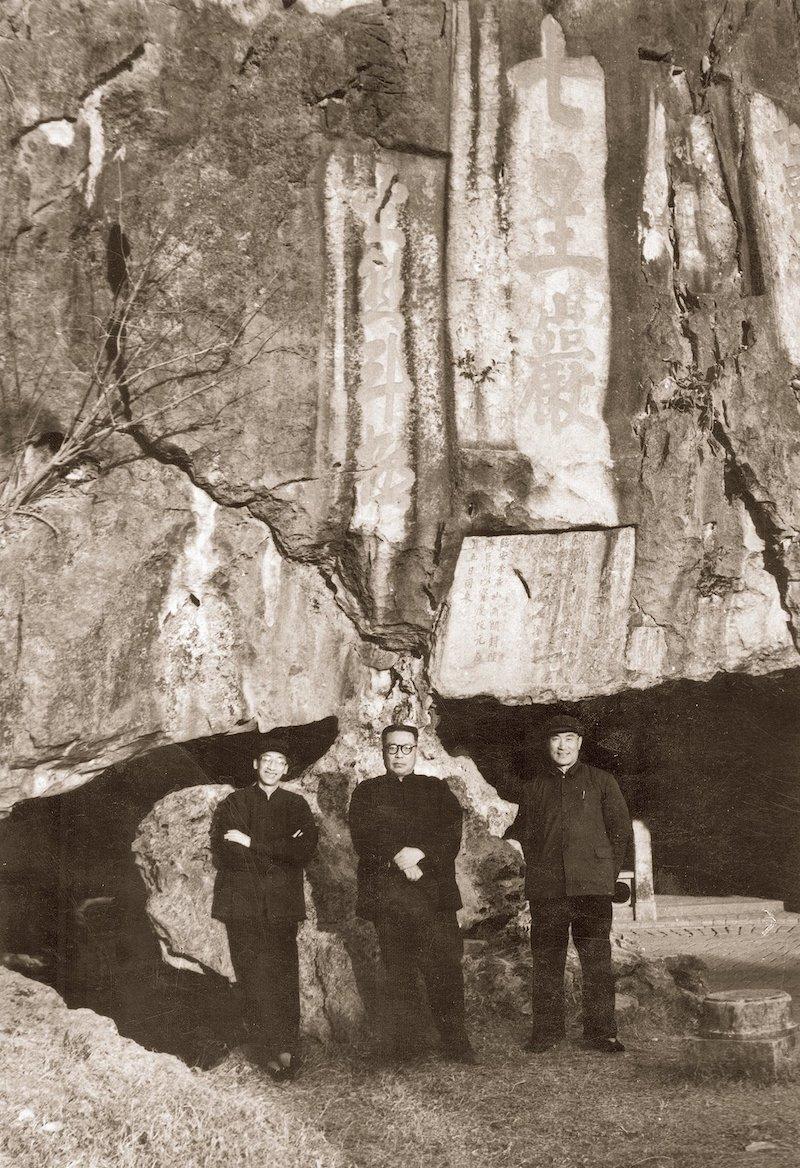

1962 Chinese ancient calligraphy and painting appraisal group, from left: Zhang Heng, Xie Zhiliu, Liu Jiuan at Qixingyan

1983 Chinese ancient calligraphy and painting appraisal group, from left: Xie Chensheng, Liu Jiuan, Yang Renkai, Xie Zhiliu, Qi Gong, Xu Bangda, Fu Xinian

The common sense in calligraphy and painting appraisal is "identification through comparison". The appraisal activities are carried out through the comparison of a large number of images and inscriptions between authenticity and falsity, real and real, and fake and falsity. Image research is far from being satisfied with the multiple comparisons between images, but focuses more on finding the connection between various things with the image as the center.

What is ancient painting appraisal? Qi Gong once summed it up in one word: to identify the authenticity (determine the era and author of the ancient painting, etc.) and to determine the quality (determine the artistic level of the ancient painting, etc.). Image textual research is to solve deeper problems after image appraisal. For example, Dong Yuan's "Dragon Sleeves and Proud People" solved by Qi Gong is one of the most typical cases. After completing the appraisal of its authenticity and quality, he further studied a series of issues such as the characters, objects and regional customs in the painting, and took the lead in entering the depth of image textual research.

The scroll of "Dragon and Villagers in the Suburbs" attributed to Dong Yuan in the Five Dynasties, collected by the National Palace Museum in Taipei

When facing a group of images with rich and complex contents in an ancient painting, in order to defeat them one by one, the textual research can adopt the method of decomposition research, just like medical treatment is the method of "overall coordination and diagnosis and treatment by discipline". Different painting subjects have different textual research methods. For example, figure painting is more restricted by court politics and social trends, and deity painting is more influenced by religion. Landscape and flower, bird and animal paintings are more nourished by philosophical thoughts and aesthetic concepts. The same is true for different image contents. In order to solve the image problem, we cannot stick to one or two methods. As long as the method is scientific and can find the answer, there is no taboo. This requires classification research by decomposing the picture and image. It can be determined according to the image. There are three commonly used methods, which can also be combined and used.

(1) According to the subject areas involved in the images, the images and their contents are studied in different disciplines. For example, the "Zhuo Xie Tu" scroll attributed to Hu Wei in the Five Dynasties has different opinions on its age. The study of this picture can be divided into several individual images, and different disciplines can be used to study different image groups separately. For example, the content of the two people sitting opposite each other in the painting can be inferred from the history of ancient diplomacy, ethnology and folklore can be used to identify the ethnic affiliation of the hair and clothing in the painting, the age and popular region of the melon-shaped pot in the painting can be analyzed from the history of ceramics, the origin of the vertical konghou in the painting and the spread of the dance can be identified from the history of national music, the ethnic characteristics of the carpet and saddle pad patterns in the painting can be explored from the history of dyeing and weaving, and the horse breeds in the painting can be verified from the history of ancient horse breeding, etc. After breaking down each type of image into individual units for study, common factors and mutual verification relationships involving the era, region, and ethnicity can be found to verify the previous identification conclusions on the author, era, and content of the picture.

The scroll "Zhuo Xie Tu" (partial) attributed to Hu Wei during the Five Dynasties, collected by the Palace Museum

The scroll "Zhuo Xie Tu" (partial) attributed to Hu Wei during the Five Dynasties, collected by the Palace Museum

(2) According to the historical sub-topics involved in the image, the image and its content are studied separately. Based on the image data of the interpreters and eunuchs of the Honglu Temple involved in the Tibetan activities in the palace in Yan Liben's "Burenian Tu" (a copy from the Northern Song Dynasty), we can integrate multiple disciplines to conduct detailed research on each special sub-topic. For example, first, we can study the relationship between the emperor and the harem in connection with the court etiquette, harem history and eunuch system of the Tang Dynasty; second, we can study the intermarriage system between the court in combination with the enthronement and marriage affairs of the Tang Dynasty; third, we can study the ethnic relations of the Tang Dynasty through the ethnic politics and translation affairs of the Tang Dynasty; fourth, we can explore the narrative method of figure painting in combination with the development of art history in the early Tang Dynasty. We can also study the history of ancient court copying and whether there is a special background for the copying of this work in the Northern Song Dynasty based on the characteristics of this painting as a copy from the Northern Song Dynasty.

Tang Yan Liben (Northern Song copy) "Stepping on the Buddhist Monk's Chariot" scroll, Palace Museum

(3) According to the special art history issues involved in the image, the image and its content are studied separately. For example, by examining the details in the image and the evidence of textual materials, the relationship between the painter, his image and the era is solved. This involves a series of micro and macro issues such as ancient society and art history. In terms of figure painting, it can be as small as confirming the level of material civilization of the society at that time, or as big as revealing the omen or outcome of the great social and political changes in a certain historical period; in terms of landscape painting, it can be as small as verifying whether the region depicted is real or imagined, what regional characteristics are integrated and the achievements in artistic language, or as big as the painter or the author's political confidence in the society at that time and the ideological motivation. The study of the influence of ancient painting art, such as the study of collection itself, aims not only to confirm how the picture was circulated, but also to enter the process of examining the region and scope of the image's influence by tracing the footprints of the collection. For example, according to the analysis of the inscriptions and collection seals of Wang Ximeng’s A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains scroll in the Northern Song Dynasty, the collection route of the painting is: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (entered the palace once) → Cai Jing → Emperor Qinzong of the Northern Song Dynasty (entered the palace twice)… → Empress Wu of the Southern Song Dynasty (entered the palace three times)… → Gao Ruli of the Jin Dynasty… → Pu Guang of the Yuan Dynasty → Shengyin Temple in Dadu… → Liang Qingbiao of the late Ming and early Qing Dynasty → Qing Palace (entered the palace four times) → Pseudo-Imperial Palace Puyi… → Jin Bosheng of modern times → Jin Yunqing → State Administration of Cultural Heritage → Palace Museum (entered the palace five times)1. Based on this, we can unfold the influence of the painting on the court inside and outside the court of the early Southern Song Dynasty, and the court art of the Yuan and Qing Dynasties. To study the artistic influence of a certain ancient calligraphy and painting in the past dynasties, we should follow the collection route of the collection and query the collectors and social circles along the way to capture which people and regions the painting has had a great degree of artistic influence on, which influences are direct, and which influences are indirect. Some direct and indirect evidence can be found in the collection route.

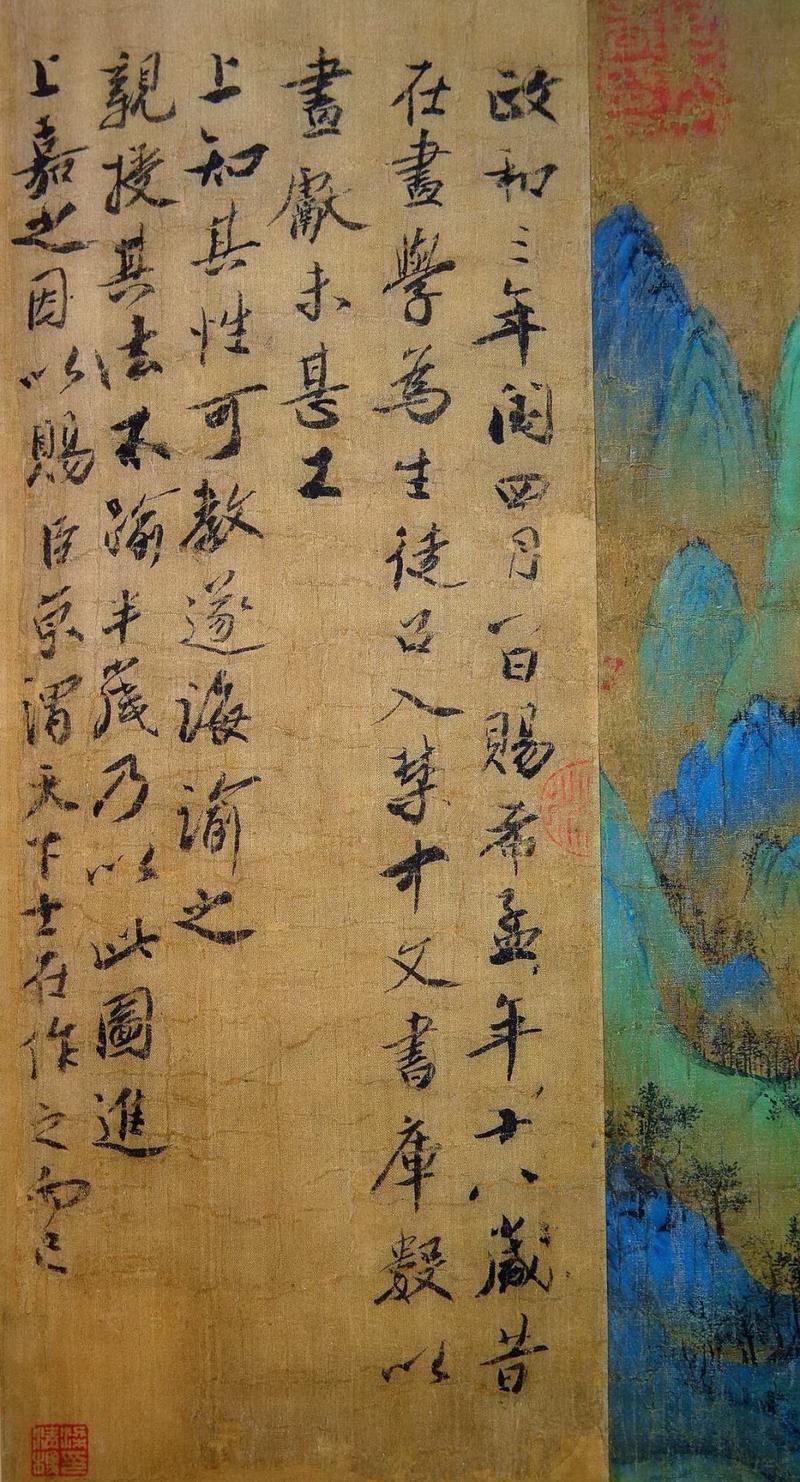

Postscript by Cai Jing on Wang Ximeng's A Thousand Miles of Rivers and Mountains in the Northern Song Dynasty

Yu Hui, General Theory of Image Research, Zhejiang University Press, 2024 edition

(This article has been edited for publication, and the title is added by the editor)