The exhibition "The Last Nobles - 18th Century European Master Paintings from the Uffizi Collection", which brings together works by more than 50 European artists including Goya, Tiepolo, Canaletto, Boucher, Chardin, etc., is currently on display at Shanghai Dongyi Art Museum. This exhibition is the fourth exhibition of the "Five Years and Ten Exhibitions" cooperation project between Dongyi and the Italian Uffizi Gallery. Through paintings, aristocratic jewelry, handicrafts, sculptures and other forms, it reproduces the artistic heritage left by the Medici family to the world.

For this exhibition, curator Alessandra Griffo recommended to The Paper more than 10 works that she thought were most worth seeing, and told the artistic stories behind the exhibits.

Portrait of Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor, Maria Theresa of the House of Habsburg, and their Thirteen Children

Martin van Meytens, Portrait of Emperor Francis I, Maria Theresa of Habsburg and their Thirteen Children, 1756

This is a typical luxurious dynastic portrait, which was very common in Europe in the 18th century. In the painting, the royal couple sits solemnly, surrounded by their many descendants. At that time, the royal family ensured an effective network of relationships through marriages with other countries. The painter Martin van Maytens was the official portrait painter of the Habsburg-Lorrain family. It is known that he created three versions of the royal family, starting in 1754, with about a year between each version. The work in the Uffizi Gallery is the last in the series and shows the final composition of the family. In the first work, which is collected in the Schönbrunn Palace in Austria, there are only eleven children in the painting, while the number of children has become twelve in the second work collected in the Palace of Versailles.

If we ignore the number of children and the slight variations in the accuracy of the portraits, the three paintings are very similar, because the main purpose of this work is to convey a perfect image of one of the great powers that dominated the West before World War I. The painting tries to create an atmosphere of family affection, but in the process of repeating this theme unchanged for many years, it loses all spontaneity.

Emperor Francis I opens the scene, sitting on a carved and gilded wooden throne, holding the imperial emblem in his right hand. The emblem features a scepter, the ancient octagonal crown of the Holy Roman Empire and a cross sphere, the sphere representing the world and the cross on top, to prove the legitimacy of the imperial power as a Christian state. Symmetrically with him is the image of Empress Maria Theresa, who was also the Queen of Hungary. On the left, Marie Antoinette is the youngest child in the cradle, the future Queen of France and a symbol of the old system that was later destroyed by the Revolution of 1789; to the right of her mother is the eldest son, Joseph II, who will become emperor; and on the far right of the canvas is Leopold, whose father died when he was very young and who later became the Grand Duke of Tuscany. At the time of this painting, Leopold was still living with his parents and siblings in the summer resort of Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. Behind the family, in the center of the composition, we can see the Monumental Square outside the Royal Palace and the entrance guarded by two obelisks crowned with the Imperial Eagle.

A few years later, in the summer of 1765, Leopold married Maria Luisa of Spain, sister of King Ferdinand IV of Naples, who in turn married Leopold's sister Maria Carolina, thus establishing a double bond of peace between the two kingdoms. A few weeks later, the young couple came to Florence and brought with them the portrait, which would soon be placed in their children's rooms (on the second floor of the Pitti Palace). Such a dazzling portrait would allow the young archdukes to grow up with a clear understanding that they belonged to the most influential family of the time.

Equestrian Portrait of Maria Theresa de Valabrega

Francisco Goya, Equestrian Portrait of María Teresa de Vallabriga, 1783-1784

Francisco Goya, Equestrian Portrait of María Teresa de Vallabriga, 1783-1784

The work on display is one of Goya's representative works as a portrait painter. Goya has been engaged in portrait painting since 1780 until his death and has achieved success in this field. Goya's initial portraits were based on the works of his teacher Raphael Mengs and predecessors such as Diego Velázquez and Antoon Van Dyck. At the same time, he was influenced by French portrait painting and the works of British artists Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. In the end, Goya formed a very personal artistic style.

This equestrian portrait was executed by Goya in quick, loose brushstrokes. It was painted as a posthumous portrait of the now-lost María Teresa de Vallabriga, wife of Don Luís of Bourbon, brother of King Charles III of Spain. According to letters written by the artist to his friend Martín Zapater, this equestrian portrait of María Teresa was nearing completion in early July 1784. It was intended to be paired with Francisco Sasso's portrait of Don Luís himself on horseback. In the overall composition, Goya tended to the conventions of portraiture usually reserved for monarchs, modeled on the equestrian portrait of Queen Isabella of Spain by Velázquez, now in the Prado Museum, which Goya had copied as an engraving in 1778. In the sketch, Maria Theresa is clearly outlined, her face is hidden by a feathered hat, and she is holding a white-haired horse tightly, showing her skillful horsemanship. Her elegance and calmness stand out against the wild, stormy background. Her costume is dark blue, which clearly echoes the background color of the Bourbon coat of arms.

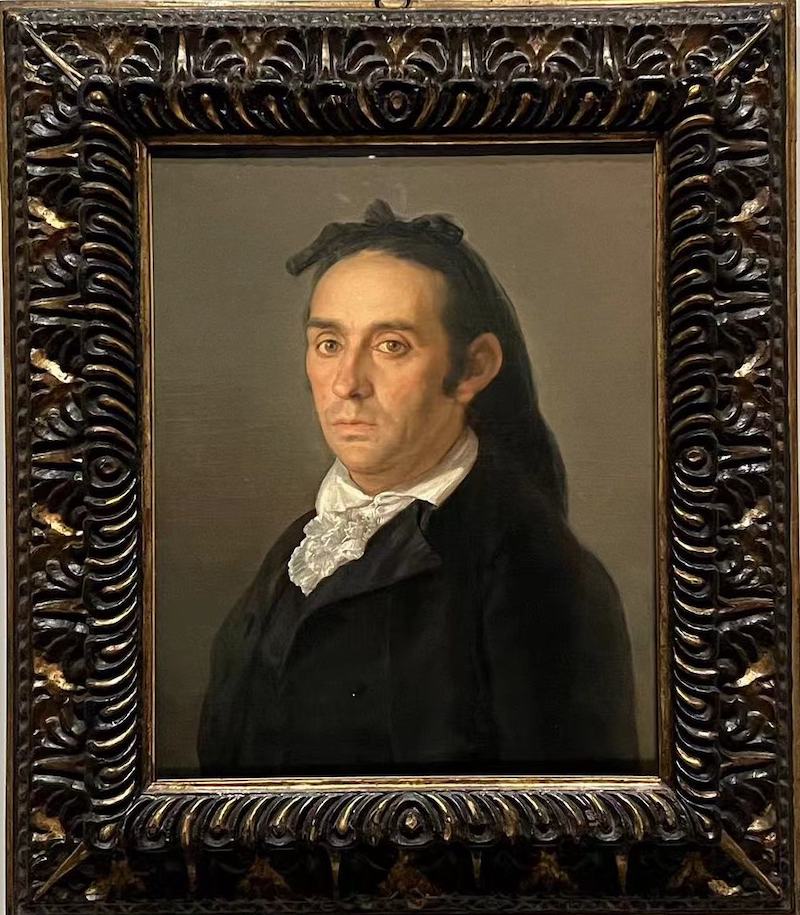

Portrait of a Bullfighter

Francisco Goya, Portrait of a Bullfighter, circa 1797

The portrait dates back to 1797. It is a representative work of the style of portraiture that Goya developed after 1792. At that time, he adopted a more relaxed and casual approach to painting than before due to his serious illness, and paid more attention to depicting the subject's psychology.

The mature man is shown in three-quarter profile, against a semi-dark grey-brown background. He is dressed in a black wool suit over a white shirt with a lapel and ruffled lace on the front. His long black hair is held up with a netted headband and tied in a bow, as was popular in Spain at the time. This is also reflected in many of Goya's other figures. The figure's head is slightly angled from the bust, and the gaze is directed towards the viewer. The figure's mass is outlined with light and lively strokes, with broader and faster strokes for the clothes and hair, while the relaxed muscles of the face and the shining reflections in the eyes are rendered with more delicate strokes.

Often, the figure is described as a "bullfighter", and is sometimes identified as Pedro Romero, the famous bullfighter of Ronda. However, this identification, based on the similarity of the two faces, especially the shape of the eyes, does not seem entirely convincing. Nevertheless, given Goya's interest in paintings of bullfighting from the turn of the century, it is possible that the figure was a bullfighter.

Self-portrait with my family

Giuseppe Maria Crespi, Self-portrait with Family, 1708

This small work, a vivid and moving self-portrait of the artist, was sent from Bologna to Archduke Ferdinando in 1708, his biographer Zanotti tells us, "to wish him a merry Christmas." In response, the Florentine prince sent an exquisite box "full of tea and tea-drinking utensils, all of the finest silver, and of excellent workmanship."

In the history of relations between patrons and artists, gifts, medals and honours are not uncommon, sometimes as a substitute or supplement to monetary rewards from the former. But in this work, there is something different. In fact, we see a particularly casual self-portrait. Compared with other known works of the time, this self-portrait is more casual. In the painting, Crespi respects the traditional portraiture and depicts himself with palette and brush. In other words, the characteristics of this work reveal a very familiar and relaxed relationship between patron and painter, who obviously felt entitled to give such a personal creation in the name of mutual respect, affinity and taste.

The dynamic composition of the painting, with the painter in his house clothes, his wife sewing on her lap, and the two children, with typical childlike innocence, absorbed in their play, has been seen by some as an accurate expression of their intentions, which were to yearn for a simple life and enjoy the pleasures of intimacy.

Giuseppe Maria Crespi satisfied his passion for genre painting with great sensitivity. In addition to its autobiographical nature, this self-portrait also contains the seventeenth-century tradition of careful attention to nature, which is reflected in its plain composition, simple attitude, warm tones and accurate light and shade. However, even in such a small work, there is another detail that deserves our attention. It is the painting within the painting. In the painting, the painter stopped working and preferred to distract himself with innocent games with children.

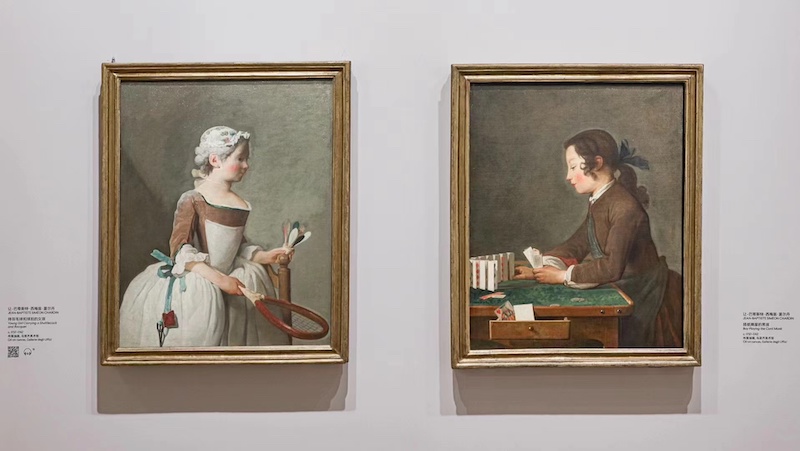

"Girl with Badminton and Racket" and "Boy Building the House of Cards"

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, Young girl carrying a shuttlecock and racquet, circa 1737-1742; Boy playing the card monk, circa 1737-1742

The two paintings were acquired by the Uffizi from a private collection in 1951. Both paintings are signed by Chardin (Girl with Racket, top right, Boy with Table, side, drawer, right), but not dated. There are also two paintings of the same subject and size, one of which was presented to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., by Andrew W. Mellon in 1937. The works were owned by Catherine II of Russia around 1777 and were divided at auction by Tsar Nicholas I in 1854.

Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin, Girl with Badminton and Racket

The painter's originality lies in his choice of subject matter and his equally unique ability to copy. He was the only artist to exhibit duplicate works at the Salon, describing them in the Salon catalogue as "repetitions with variations" (répétitions avec des changements). This unusual practice was adopted to ensure that his works would become part of the public consciousness and would not disappear into private collections. The uniqueness of Chardin's approach is matched by his choice of word: "repetition" (répétition), which was not common at the time and had no fixed meaning, while "copying" was the term of the time. The paintings are derived from the fantasy paintings of the Netherlands and Flemish countries in the 16th and 17th centuries, but the painter's skill in transforming the subject of moral precepts into a new and ambitious genre painting is admirable.

Jean-Baptiste Simeon Chardin, The Boy Who Built the House of Cards

In the paintings in the Uffizi and Washington collections, the boy is wearing an apron with a pin inserted near the cuff of his left sleeve, suggesting that he is a domestic servant who has just finished work. The pin is more than just a detail: in children's games, pins were also used as gambling chips and sometimes to connect playing cards.

Madonna Sewing

Francesco Trevisani, Madonna Sewing, circa 1692–1700

This work is one of a series of paintings characterized by its intimate style and rich everyday details, which had great success in Rome. The same work of similar size is The Dream of St Joseph, also in the Uffizi Gallery.

The work once belonged to Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni, grandson of Pope Alexander VIII, who presented it to the Florentine prince during his visit to Florence in 1709. The provenance of the painting can be seen both in the eagle and the cardinal’s wide-brimmed tasseled hat seen on the vase on the far left, as well as in the coat of arms, and in the words of the biographer Lione Pascoli, who in his Life of Francesco Trevisani, mentions a painting of the Dream of St. Joseph that the artist had made for Cardinal Ottoboni, a pair with the one on display.

The artist, who was trained in Venice, moved to Rome in 1678 and lived in the home of a powerful priest, who introduced him to the literary institution Accademia dell'Arcadia, founded in 1690, which advocated a return to the simplicity and naturalness of classical art. This work was created in this atmosphere, and its clear composition and subtle colors add a sense of intimacy to the picture. The work is interspersed with everyday details such as sewing and baskets, depicting the Virgin Mary holding a needle and thread and having a tender conversation with her son Jesus. Their highly dramatic movements are consistent with Ottoboni's interests (such as drama) and reveal his love of scenes. The expression on Jesus' face is reminiscent of his future suffering and death on the cross.

Grand Canal View and Doge's Palace View in Venice

Giovanni Antonio Canal, also known as Canaletto, View of the Grand Canal, 1726-1728

Canaletto learned to paint in the workshop of his father, Bernardo, who was a set painter, and Canaletto studied for a while with his father. During a stay in Rome in 1719, Canaletto was inspired by the work of Dutch landscape painter Caspar Van Wittel and began to paint landscapes. Returning to Venice, he began to depict the city's most striking sights, with a dynamic and detailed style, strict perspective, and a focus on the texture of different surfaces, resulting in an atmospheric and bright naturalism. To obtain the initial view, Canaletto also used a camera obscura, a portable optical device that projected an inverted, illuminated image of the lens's view onto a flat surface inside the device.

Although these works are highly credible, they are not a simple record of reality, but are infused with the painter's own poetic imagination. Venice was the capital of the Republic at the time. Although the political and economic situation had declined, the city presented a prosperous and peaceful scene. The morning light or midday light illuminated the canals and squares, making the outlines of the buildings clearer and reflecting dazzling light. These pleasing features determined that the painter's works were very popular locally and throughout Europe. The British, in particular, were particularly fascinated by the architecture and atmosphere of Venice, and Venice became a must-visit place for them.

The exhibition features some of Canaletto's most popular works, symbols of Venice's splendor and power accumulated over centuries of maritime dominance. He repeated these two works several times in different sizes, with slightly different perspectives, and with variations in light, atmosphere and characters. The first work is inscribed on the reverse, identifying the work and its date. The painting depicts a particularly monumental stretch of the Grand Canal, lined with aristocratic buildings. On the left side of the painting is Palazzo Balbi, radiant in the sun; on the right is Palazzo Contarini, in the shadows. At the end of the perspective, we see the Rialto Bridge, slightly foreshortened, with the Cathedral of San Giovanni and Paolo dominating.

Canaletto, View of the Ducal Palace in Venice, circa 1735-1750

The second work, View of the Doge's Palace in Venice, is of uncertain date, but probably dated between the 1730s and 1750s. This work shows a small perspective. From San Marco, the front of the pier is visible. The magnificent complex of buildings is the seat of the political, religious, economic and cultural institutions of the Venetian Republic. Starting on the left, we can see the Mint, the Marciana Library (with the Campanile of San Marco behind it); then Piazza San Marco, the Doge's Palace, the New Papal Palace, and finally the Palazzo Dandolo, located between two groups of low buildings. The perspective chosen by the painter also allows a corner of San Marco's Basilica to be frozen in the background, and further away are the bell tower and the arches of the commercial street.

In both paintings, the human figures show the audience the daily life of the city. The Grand Canal is dotted with ornate gondolas and other simple boats. The porters on the boats are transporting barrels and bundles of goods; the docks, St. Mark's Square and the Doge's Palace are crowded with all kinds of people.

Capriccio: Houses and Bell Tower by the Lagoon

Francesco Guardi, Capriccio with Bridges over a Canal, 1770

In the centre of the painting, a small white bridge spans the canal. On the left bank of the river is an uncultivated garden, on the right a church and a monastery, where a Gothic arched opening offers a glimpse of the courtyard under the shade of trees. In the background is the second bridge, whose flags flutter in a cloudy sky, directing the viewer's eye to the sea. Women and men in tricorne hats dance in this scene. They are mostly in pairs and are engaged in conversation. At the top of the first bridge, a washerwoman hangs a large red curtain in the sun, adding a touch of brightness to the otherwise cold tones of the work.

This small painting forms a diptych with another painting from the Uffizi Gallery. The artist, influenced by Canaletto, used strong white light and blocky pigment mixtures with light and energetic brushstrokes. This painting has been identified as a late work of Guardi. The painting seems simple in content, but it actually has a very complex composition due to the strong contrasts of light and the visual connections between the elements inside. This work is an excellent example of Guardi's ability to create "capricci", which means imaginary urban or rural landscapes. In his works, the artist reworked his memory of real places and combined them in a strict perspective structure, giving his created images credibility. In this sense, "capricci" can be said to be the opposite of "vedute" (landscape), which represents real places, even if the landscape is recreated according to the artist's personal interpretation and poetic filter.

Like Canaletto and other Venetian landscape painters of the time, Guardi was devoted to both types of painting. In the Capriccio he found not only the opportunity to give free rein to his emotions (an impulse that was necessarily suppressed in landscapes), but also the opportunity to appeal to different art markets. In fact, foreign tourists liked to buy landscapes when they traveled, while Venetian art buyers favored the Capriccio, which best highlighted the painter's stylistic features and delighted the viewer with its dreamlike visual effects.

Characteristic Costumes of the Kingdom of Naples

Installation view, Alessandro D’Anna and Antonio Perotti, Costumes of the Kingdom of Naples, circa 1785–1799

In order to find original subjects for the porcelain produced by the Royal Ferdinand Porcelain Factory, founded in Naples in 1771, the factory launched an ambitious investigation to record the different styles of clothing of the kingdom's inhabitants. Foreign visitors were amazed to find that in every neighborhood of every village and town around Naples, women dressed in a unique way. Ferdinand IV of Naples supported the campaign because he realized how important it was to enhance the pride of the locals and praise their hard work.

In 1782, the porcelain factory selected a series of artists to serve it. The artists' mission lasted for more than ten years and they traveled throughout southern Italy at the time, including Sicily, creating dozens of works, including drawings, tempera, gouache and engravings. The artists' works were used as models for the decoration of tableware and other items, and were highly praised at the time and later. At the same time, these creations also inspired the creations of other factories.

Characteristic Costumes of the Kingdom of Naples

Characteristic Costumes of the Kingdom of Naples

When Ferdinand IV visited his brother-in-law Pietro Leopoldo and his sister Maria Luisa, he wanted to bring a gift that included 42 gouaches and 18 statues in different costumes of the kingdom. In the following years, the number of these works increased to 210. Four of them are on display in this exhibition. The diversity of the works is reflected in the paintings, even though they show men, women and children dressed in typical, colorful and picturesque local costumes.

A Lady in Turkish Costume Reading

Jean-Étienne Lyotard, A Lady in Turkish dress reading, circa 1753

A woman in Turkish dress sits on a sofa, leaning sideways with her feet up, absorbed in reading a book. The space, including the window with iron bars, is a red chalk depiction of Lyotard’s bedroom in Constantinople, where he lived from 1738 to 1742. The woman’s dress depicts carnations, roses, jasmine and sweet heather, all symbols of love, similar to the floral white tulle dresses worn by women in many of the artist’s pastels.

Although inscribed on the reverse, "Maria Adelaide of France", this is not a portrait of Louis XV's fourth daughter. The subjects are clearly expatriates from Constantinople, the same women who appear in many of Lyotard's pastels, dressed in local costume. These works often show women in Turkish dress, seated on couches in deep thought. Despite their distinctive portraiture elements, the works bear generic titles. In keeping with the pan-European Turkish fashion that arose between 1650 and 1750, Lyotard also depicted Europeans in Levantine dress.

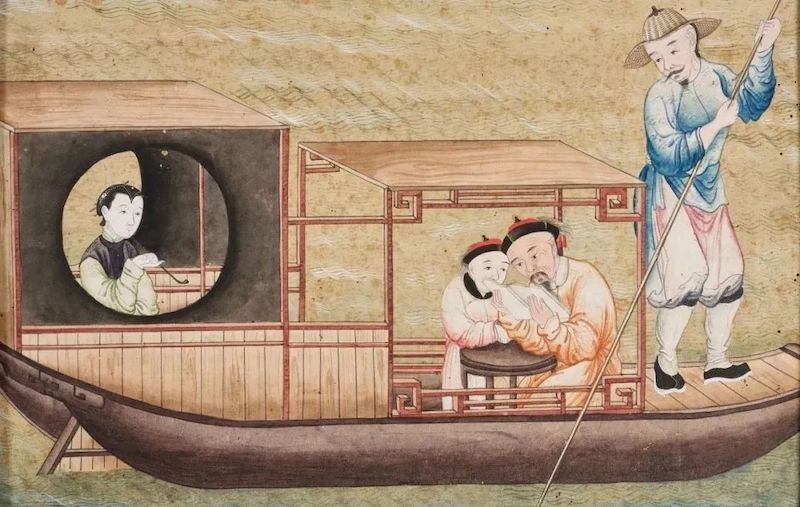

Chinese Export Painting "Traveling by Boat"

Chinese Export Painting (Chinese Artifact), Boat Trip, circa 1770

At the beginning of his reign, from 1795 to 1791, Grand Duke Pietro Lopoldo of Tuscany bought around 200 export paintings, including Chinese silk textiles, on the markets of Brussels and Livorno. His tastes were clearly in sync with Europeans’ thirst for China and the East, revealing a fascination with the exotic. In 1790, Giuseppe Bencivenni Pelli, director of the Uffizi Gallery, wrote of a visit to the great villa of the Dukes of Castello outside Florence where he admired “real views” of these and other distant lands. These views were mounted on canvas and framed with black-dyed wooden ornaments to imitate the surface effect of lacquer. The names of the paintings exported from China were related to their place of origin and the trading companies there. Most of these works were produced in the Guangzhou area, which was the only open port at the time for trade with countries such as the Netherlands, Britain and France. There were specialized workshops for this industry, which satisfied European curiosity about the cultivation of rice and tea, as well as the production of silk and porcelain.

Ironically, we now know that these artworks have little in common with the great Chinese artistic tradition, but the variety of subject matter, the detail of each scene, the vivid colors, and the "luster" created by the special treatment of the paper and the exquisite processing technology still fascinate Westerners.

Today, as then, our ultimate goal remains to create a magical place where different civilizations come together.