The Paper has learned that starting from April 18, the National Gallery in the UK will exhibit Caravaggio’s last work, “The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula,” along with another late work by Caravaggio, “Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist.”

The Martyrdom of Saint Úrsula depicts the most dynamic and dramatic scene, and unlike the previous paintings, this one does not feature a model in a fixed pose. This makes the painting freer and more impressive. It also includes a self-portrait of Caravaggio, who peeks over the saint's shoulder.

Caravaggio, The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula, 1610, from the collection of the Italian banking group Banco San Paolo

Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610) was one of the most revolutionary figures in Western art. His paintings, highly original and emotional, with intense naturalism, dramatic lighting and powerful storytelling, had a lasting impact on European art that still resonates today. But Caravaggio was arrogant, rebellious and a murderer, and his short and turbulent life matched the drama in his work.

The National Gallery exhibition "Caravaggio's Last Paintings" focuses on Caravaggio's last days. His last work "The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula" (1610) was loaned by the Italian banking group Banco Sanpaolo. This is also the reason why the work was re-identified as Caravaggio's work in 1980 based on archival letters describing its commissioning process. In contrast, the National Gallery's collection of another late Caravaggio work "Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist" (c. 1609-1610)

"Caravaggio's last painting is deeply emotional and tragic, and seems to reflect the artist's confusion and anxiety as he prepared to leave Naples and return to Rome," said Dr Gabriele Finaldi, director of the National Gallery.

Caravaggio's Last Days

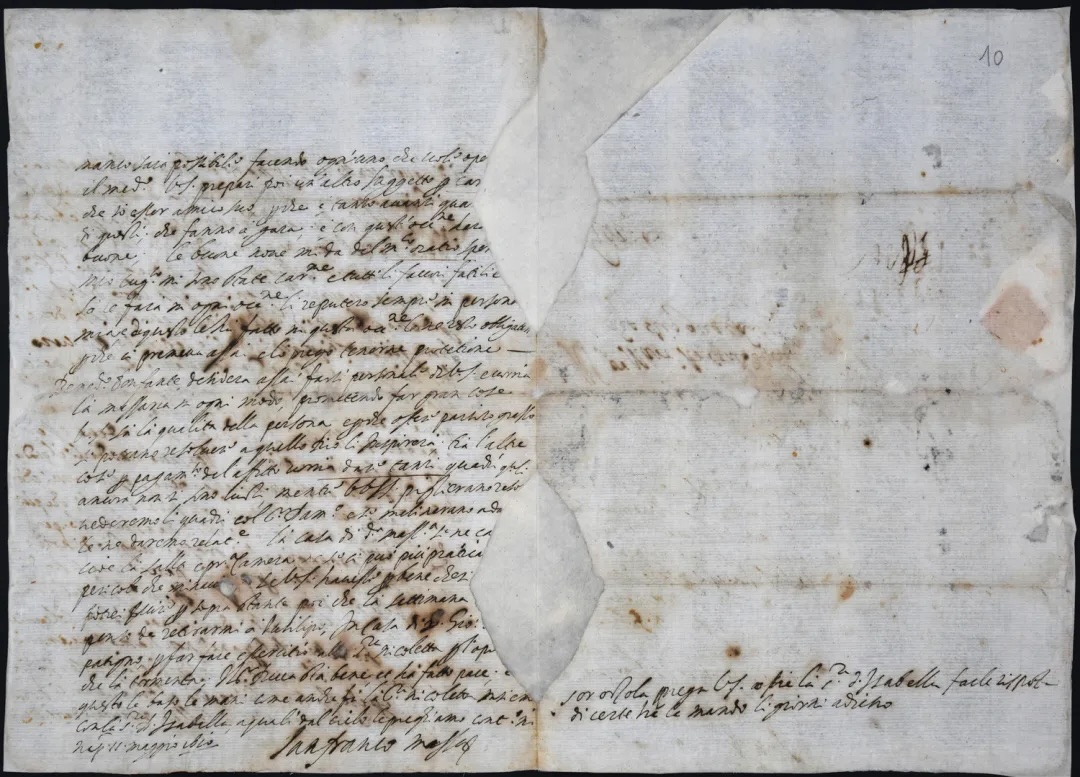

The commissioning letter confirming the Martyrdom of St Úrsula’s attribution to Caravaggio will also be on display in the exhibition, this time from the Naples State Archives to be shown in the UK. It records the final stages of the commissioning process as the painting was sent from Naples (where it was created) to Genoa (where its patron, Marcantonio Doria, lived).

Letter from Lanfranco Massa to Marco Antonio Doria, May 11, 1610. © State Archives of Naples

The Martyrdom of Saint Úrsula, which includes a self-portrait of Caravaggio peering over the saint’s shoulder, was painted during the last months of his life. The finished painting was dispatched from Naples on 27 May 1610 and arrived in Genoa on 18 June. Only a few weeks later, in July 1610, Caravaggio left Naples hoping to return to Rome, as he believed he would be able to obtain a pardon for a murder committed in 1606, a crime that forced him to flee south. However, he never made it to Rome, and died in Porto Ercole on 18 July 1610.

The Martyrdom of Saint Úrsula (detail), later a self-portrait by Caravaggio

In The Martyrdom of Saint Úrsula, Caravaggio departs from the traditional iconography of Saint Úrsula, who is usually depicted only with symbols of martyrdom, and with one or more virgin companions. Instead, he chooses to depict the moment when the saint refuses to marry a non-Christian Hun, and is shot with an arrow by him. The tight composition brings great dramatic emphasis to this scene. The whole scene is filled with the complex interplay of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, that is characteristic of Caravaggio's paintings.

The viewer is confronted with an intricate depiction of hands: the guilty hand that has just shot the arrow, Úrsula’s hand framing the fatal wound in her chest, and the hand of the bystander, belatedly intervening between the two protagonists. Caravaggio includes his own self-portrait on the right side of the painting, looking on helplessly.

Caravaggio, Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist, circa 1609-1610, National Gallery, London

The National Gallery's Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist was also created at the end of Caravaggio's life. The Gospel of Mark tells the story of John the Baptist's death: John criticized King Herod for marrying his late brother's wife Herodias, and she sought revenge. At Herod's birthday party, Herodias' daughter Salome delighted King Herod with her dance, so much that he promised to give her anything she wanted. Encouraged by her mother, she asked for John the Baptist's head, so King Herod ordered John to be executed.

Caravaggio, Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist (detail)

Caravaggio again reduces the story to its essence, focusing on the human tragedy and conveying the emotional power of the scene through more muted colors, stark contrasts and dramatic gestures. The brutal executioner places John's head on a tray held by Salome. Salome's serious expression and sidelong glance are full of mystery. An elderly maid clasps her hands together, setting the emotional tone of sadness. The close-up of the half-length figures enhances the dramatic impact of the scene. Some studies have suggested that the head painted on the tray is Caravaggio's own head.

Caravaggio, Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist (detail)

This is characteristic of Caravaggio's mature work, in which the deceptively simple composition conceals a complex physical and psychological interaction between the main characters. Salome and the executioner are subtly linked by their poses - the angles of their heads echo each other, the strong side light falls on their faces - but their roles are very different. The executioner hands the head to Salome with a blank expression: although he wields the knife, the blame for John the Baptist's death lies with her.

The exhibition provides an opportunity to explore Caravaggio's late paintings, the violence he represents, and the reflections on violence in our own time. The exhibition program and activities will focus on the image of Saint Úrsula, allowing the audience to gain a deeper understanding of her story. At the same time, the narrative of male violence in Caravaggio's paintings will also be paid attention to and examined.

The unknown side of Caravaggio

Caravaggio was born as Michelangelo Merisi, and took his hometown in Lombardy, northern Italy, as his stage name. In 1592, at the age of 21, he moved to Rome, the art center of Italy, to paint in the then-popular studio of Giuseppe Cesari, which was very attractive to young artists eager to study classical architecture and famous works of art.

Caravaggio, "Boy with a Basket of Fruit", painted around 1593-1595, acquired by the Borghese Gallery in 1607 (exhibited at the Pudong Art Museum until April 12)

In his first few years he struggled, specializing in still lifes of fruit and flowers. Caravaggio's best-known works from this period include the small Boy Peeling Fruit (his earliest known painting), Boy with a Basket of Fruit, and The Sick Bacchus, as well as a self-portrait painted while he was recovering from a serious illness, after he was no longer employed by Cesari. All three of these paintings show the realistic side of Caravaggio that would make him famous. Boy with a Basket of Fruit, currently from Rome's Galleria Borghese, is on display at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum and features his friend and companion, the Sicilian painter Mario Minniti, who was painted at around 16 years old.

Caravaggio later gradually turned to half-length figure paintings for street sales. The most representative of these is "Boy Bitten by a Lizard". This symbolic yet realistic work was once exhibited in the Shanghai Museum.

Caravaggio, "Boy Bitten by a Lizard", 1594-1695, National Gallery, London

In 1595, Caravaggio's fortunes changed. The young painter's talent was spotted by the famous Cardinal Francesco del Monte, who took him into his home. Thanks to the cardinal's connections, Caravaggio received his first public commissions, and his striking and innovative works quickly made him famous. Between 1600 and 1606, Caravaggio became "the most famous painter in Rome," his enhanced chiaroscuro making his subjects dramatic, while his precise observation brought realism to a new level of emotional intensity. Roman painters were attracted by this new style, and young painters in particular gathered around Caravaggio, praising him as a unique imitator of nature and considering his work a miracle.

Caravaggio, The Supper at Emmaus, 1601, National Gallery, London

Meanwhile, Caravaggio led a frenetic life. Even in a time and place where disputes were commonplace, he was notorious for his frequent brawls. In 1606, an argument with a “very polite young man” over a woman or a game of tennis escalated into a sword fight, and Caravaggio accidentally stabbed the man. Although he may not have intended to kill him, the man died from the sword wound. Previously, his upper-class patrons had dealt with a series of his escapades, but this time they were powerless. To avoid legal action, Caravaggio fled Rome, confident that he would soon be pardoned.

Caravaggio fled to Naples and then to the island of Malta, an independent sovereign state and the headquarters of the Order of Malta, a religious military order similar to the Knights Templar. Caravaggio hoped to become a member of the Order so that he could better seek a pardon from the Pope for his murder. To this end, he was granted membership in the Order in exchange for a painting of the Beheading of Saint John the Baptist. However, he later had a conflict with a knight and was expelled from the Order. His major works during his time in Malta include the huge Beheading of Saint John the Baptist (the only work he signed) and the Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Attendants, as well as portraits of other leaders of the Order.

Caravaggio, Portrait of Antonio Martelli, Knight of Malta, 1608-1609, Uffizi Gallery, Florence (on view at Pudong Art Museum until April 12)

Caravaggio then traveled to Sicily, but after nine months, returned to Naples, where he was once again involved in a bar fight and was badly injured. But in Naples, he painted The Denial of St. Peter, his last St. John the Baptist, and his last painting, The Martyrdom of St. Ursula. At the same time, the painting Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist was sent to de Wignacourt to beg for forgiveness. It is possible that he also painted David with the Head of Goliath at the same time, in which the young David looks with strange sadness at the giant's injured head, which is still Caravaggio's head. He may have given this painting to Scipione Borghese, the cardinal's nephew and a passionate art lover who held the power of pardon.

Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist, 1609-1610, acquired by the Borghese Gallery in 1613 (on display at the Pudong Art Museum until April 12)

Indeed, Caravaggio won a pardon from the Pope—which meant he could return to Rome. Caravaggio loaded his baggage onto a ship, but for some unknown reason he was arrested and had to pay to be released from prison. When he was released, he found that the ship and all his possessions had sailed away. On the way along the coast, he became ill, probably with malaria, and died a few days later, alone and febrile, in Porto Ercole. If Caravaggio had lived, he would have produced something new.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, painted around 1610, acquired by the Borghese Gallery in 1613

Dr Francesca Whitlum-Cooper, curator of late Italian, Spanish and 17th-century French painting at the National Gallery, said: “The National Gallery has an exceptional collection of Caravaggio, with the early Boy Bitten by a Lizard, the important Roman The Supper at Emmaus and the late Neapolitan Salome Receiving the Head of John the Baptist. With The Martyrdom of St Úrsula, visitors will be able to experience Caravaggio’s late work in its entirety for the first time in decades.

Note: The exhibition "The Last Caravaggio" will be on display in Room 46 of the National Gallery from April 18 to July 21, 2024; "Caravaggio and the Baroque Miracle" at the Shanghai Pudong Art Museum will be on display until April 12. This article is compiled from the WeChat official account of the National Gallery and previous reports from The Paper.