"There is the face of a fair-haired maiden, which I treasure in this little round box... For her I have composed a sad elegy, and this sweet and lasting memorial I treasure."

As the Milanese humanist Angelo Decembrio described in his 1450s On the Grace of Literature, Renaissance portraits now hang on the walls of museums around the world and hold countless secrets: covered sketches, hidden self-portraits, even giant skulls, seemingly reminding viewers that humans are mortal yet eternal in memory and image.

The Paper learned that starting from April 2, the exhibition "Hidden Faces: Covered Portraits of the Renaissance" at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will attempt to show another little-known level - many portraits were once covered by covers, and the back of the portrait usually contained another completely different image, which also included the intimate and interactive nature of the portrait.

Titian, The Triumph of Love (cover with missing portrait), c. 1545 © Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The first exhibition to examine the multifaceted portrait tradition of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe, the exhibition features 60 works by artists including Hans Memling, Titian and Lucas Cranach the Elder, emphasizing the interactive nature of veiled portraiture.

We usually think of portraits as two-dimensional works fixed to a wall, immutable and permanently visible. However, during the Renaissance, private portraits were often hidden beneath other paintings, and these paintings, which served as covers, were like a prelude to these three-dimensional, portable objects.

Marco Marziale’s Portrait of a Man has an allegorical landscape on the reverse.

These portraits “are not usually shown, but are meant to be unveiled and viewed,” says Alison Manges Nogueira, the exhibition’s curator. The portrait is the primary image, but the work as a whole is often decorated with rich symbolic images and inscriptions on the cover and back, revealing traits of the sitter while physically hiding the portrait. The viewer is invited to judge the portrait by its cover, to decode its enigmatic symbols, allegories and myths, and to uncover the person behind it, the reverse of which also reveals the identity of the sitter in form and meaning, and the work’s function as a symbol of friendship, love or political loyalty. “We should think more about the impact of other images on the whole work.”

Augustus gold coin (reverse on right), Rome, 20–19 BC,

Multi-sided portraits originated in the Netherlands in the early 15th century before spreading to Italy and other parts of northern Europe. According to Nogueira, the practice built on ancient traditions, including the tradition of unveiling sacred artworks during liturgy, hiding erotic images behind curtains, and the tradition of minting coins and medals, where the reverse image was often a celebration of the figure portrayed on the front. Fourteenth-century religious painting also influenced the genre, as many pieces had painted images on the reverse, both to protect against moisture and to "enhance the religious narrative," Nogueira said.

Altarpiece with roof decoration, Germany, circa 1490 Front and back

Altarpiece with roof decoration, Germany, c. 1490 (opened)

Rogier van der Weyden (Netherlands), Portrait of Francisco d’Este (1429-1486), circa 1460

Covers come in a variety of forms, including wooden panels that slide in grooves in the frame, hinged diptychs, curtains, boxes and lockets. While Renaissance sources confirm the prevalence of multi-sided portraits, most such works have lost their original covers and reverse images, obscuring evidence of their former construction. This meant that the tradition was long neglected. The few examples that have survived are often badly damaged or difficult to display. Double-sided portraits present similar challenges, as it is not usually feasible to display both sides simultaneously in the context of a traditional gallery wall display.

Bernhard Strigel, Portrait of Margarethe Vöhlin (left) and coat of arms on the reverse, 1527, National Gallery of Art, Washington

In some cases, paintings and their covers were separated at some point and placed in different collections. The Met exhibition re-presents one such pair—an allegorical scene by Lorenzo Lotto from the National Gallery of Art in Washington and a portrait of a woman from the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon in France. Lotto’s letters provide valuable information about the multifaceted tradition of painting, and the Venetian artist’s patron was puzzled by the sacred images he chose to decorate his covers.

Lorenzo Lotto's "Portrait of Giovanna de Rossi" in 1505 (left, in the collection of the Dijon Museum of Fine Arts, France); the cover of the portrait "Allegory of Chastity" (right, in the collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington)

“He wrote back advising his patrons that it was up to their imagination to give them meaning,” Nogueira said. “That’s still relevant to us today because these images are still confusing. At the time, they were interpreted in so many different ways.”

In addition to limiting the amount of portraits that could be seen, faceted portraits allowed artists to comment on their own work, painting allegorical scenes that reflected the portrait's character on the removable cover or reverse of the portrait. For example, Memling's Allegory of Chastity may have originally been paired with a now-lost portrait of a woman named Barbara, hoping to evoke the saint of the same name.

Hans Memling (Netherlands), Allegory of Chastity (or cover of a lost portrait), 1479-1480

Nogueira came up with the idea for the exhibition while researching a pair of double-sided portraits in the Met’s collection. The small panels were created between 1485 and 1495 by the Venetian artist Jacometto Veneziano. One, identified as a portrait of Alvise Contarini (Venice’s 106th Doge), features a tethered stag on the reverse. The other, a woman who may have been a nun, has a severely damaged reverse that appears to contain a grisaille scene (a technique in which artists use gray to mimic sculpture in two-dimensional form).

Jacques Meteau's Portrait of Alvise Contarini (left) and the reverse version of the painting, The Tethered Stag (right), circa 1485-1495, from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Two small portraits by Jacquemet, preserved in the same portrait box; the woman on the right may be Sister San Cenote; the reverse depicts themes of Love, Devotion and Sorrow.

"These pairs of portraits were originally grouped together in a box," Nogueira said. "They have long been studied and a mystery. Who they are, what their relationship is, and what the image on the back means." In the exhibition catalogue, the curator suggests that the key to solving the mystery lies in the gray-toned scene, which she identifies as the mythical hero Orpheus, playing his instrument, begging Charon, the ferryman of the River Styx, to give him a chance to find his dead wife. "Through the image of Orpheus, Alvise is not only claiming to be a widower, but also a cultured lover of music and poetry."

Reverse of a female portrait (possibly of the Sister of San Zenoto), circa 1485-1495

Contemporary viewers would "tend to favour the portrait and consider the reverse side secondary", partly because this side of the panel was often painted in the artist's studio, with the artist giving the finishing touches. A similar bias existed during the Renaissance. Around 1485, Memling painted a vase of flowers on the reverse of a portrait of a young man, creating one of the earliest still life paintings in European history. "It's really an outstanding example of how artists used the reverse side of a portrait and the cover to experiment with subjects that were not necessarily considered worthy of painting at the time," the curator said.

Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man (left) and, on the reverse, Still Life with Flowers in a Pot (right), c. 1485, © Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Ultimately, the curators hope that viewers will gain a clearer understanding of the complex subject of Renaissance portraiture through the exhibition. "When we look at a portrait, we see fragments," Nogueira said. "This is what we recognize when we look at a fragment of an altarpiece. We know it was once part of a larger work. But when it comes to portraits, we don't usually think about this, but in fact, there is a lot more for us to discover."

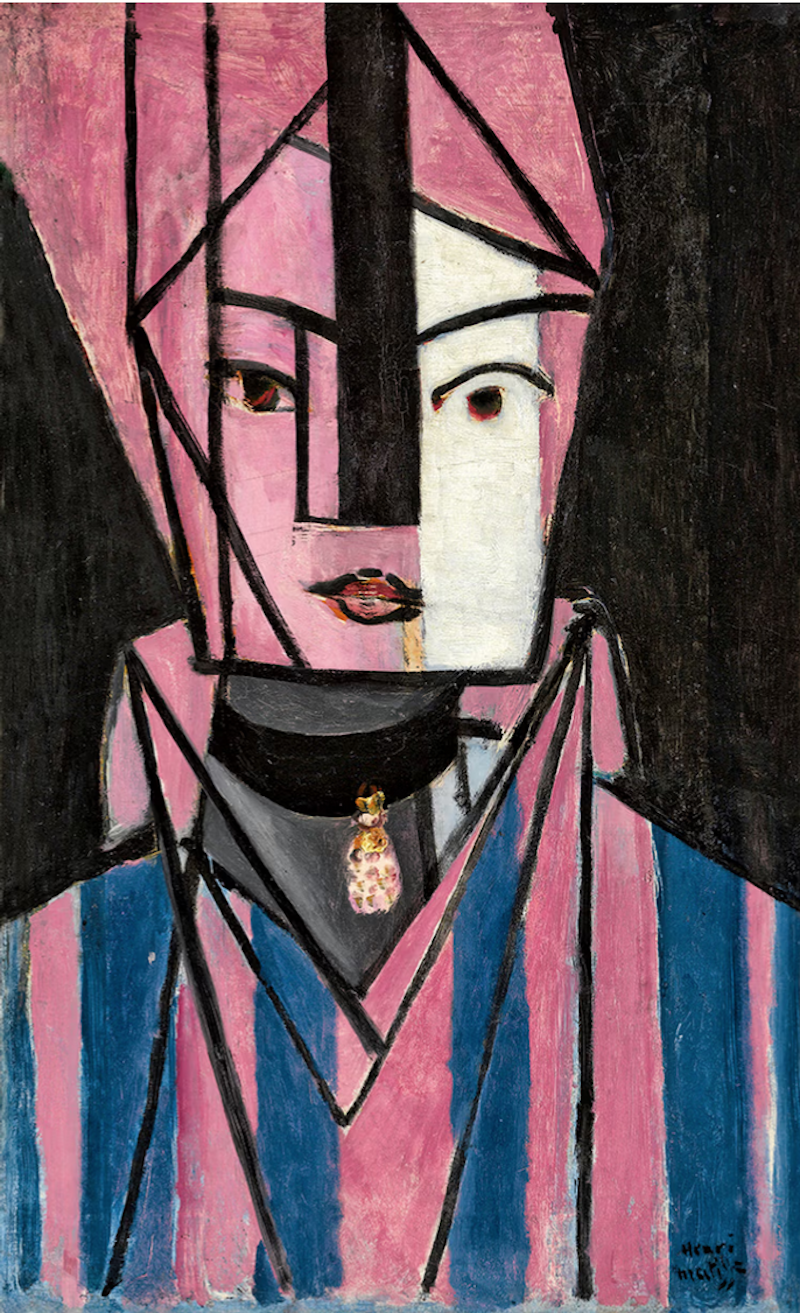

Lucas Cranach the Elder (German), Portrait of a Man with a Rosary, c. 1508

The portrait is one side of a now-removed triptych, and the young, well-dressed man appears to be in silent prayer. His ring is engraved with the coats of arms of two Dutch noble families, indicating that he is from the Netherlands. The painting was probably painted when Cranach visited the Netherlands in 1508.

Appendix: Exhibition section

Covering Secular and Sacred Art

The multi-faceted portraits of the Renaissance form part of a long tradition of hidden works of art that stretches from antiquity to the modern day.

In the sacred realm, this covering takes many forms and materials, including shuttered altarpieces, reliquaries, curtains fixed to frames or sewn from illuminated manuscripts, and veils used in Christian Lent celebrations. The covering of the sacred object enhances its sanctity, revealing that the sacred is at the heart of religious practice, activating the image and imparting sacred knowledge to the viewer.

Portraits and other types of secular images, such as nudes, were often covered by curtains or covers, which increased the sense of privacy and anticipation. In addition to protection from light, dirt, and other forms of damage, covering was essential to the viewing and significance of portraits, especially when their covers were decorated with heraldic images related to the sitter.

Simon Marmion (France), The Death of Christ, c. 1473

Simon Marmion (France), The Death of Christ, back

Pisano (Italy), Medal with the Portrait of Celia Gonzaga (obverse); Unicorn in Moonlight (reverse), 1447

15th Century Northern European Covered Portrait

Half-length portraits painted in a realistic manner flourished in the Burgundian Netherlands in the early 15th century. Similar to religious double-sided paintings, many works by Jan van Eyck and his contemporaries had imitation stone patterns (such as marble or porphyry) painted on their frames and reverses to highlight the status of the sitter and the permanence of their image in later generations. Later, under Rogier van der Weyden, the reverses of portraits were also decorated with coats of arms and personal emblems to indicate the identity and lineage of the sitter. In the 1470s and 1480s, especially under Hans Memling, the reverses of portraits and cover pages became a site for experimentation with secular imagery. The still lifes, botanical studies, fantasy scenes, and allegories in this room, which often allude to the transience of life, represent early examples of these schools of painting, which later became independent subjects.

Studio of Rogier van der Weyden, with an open book and a portrait of a man (perhaps Guillaume Filast); right, a holly branch and an inscription (on the reverse), circa 1430s

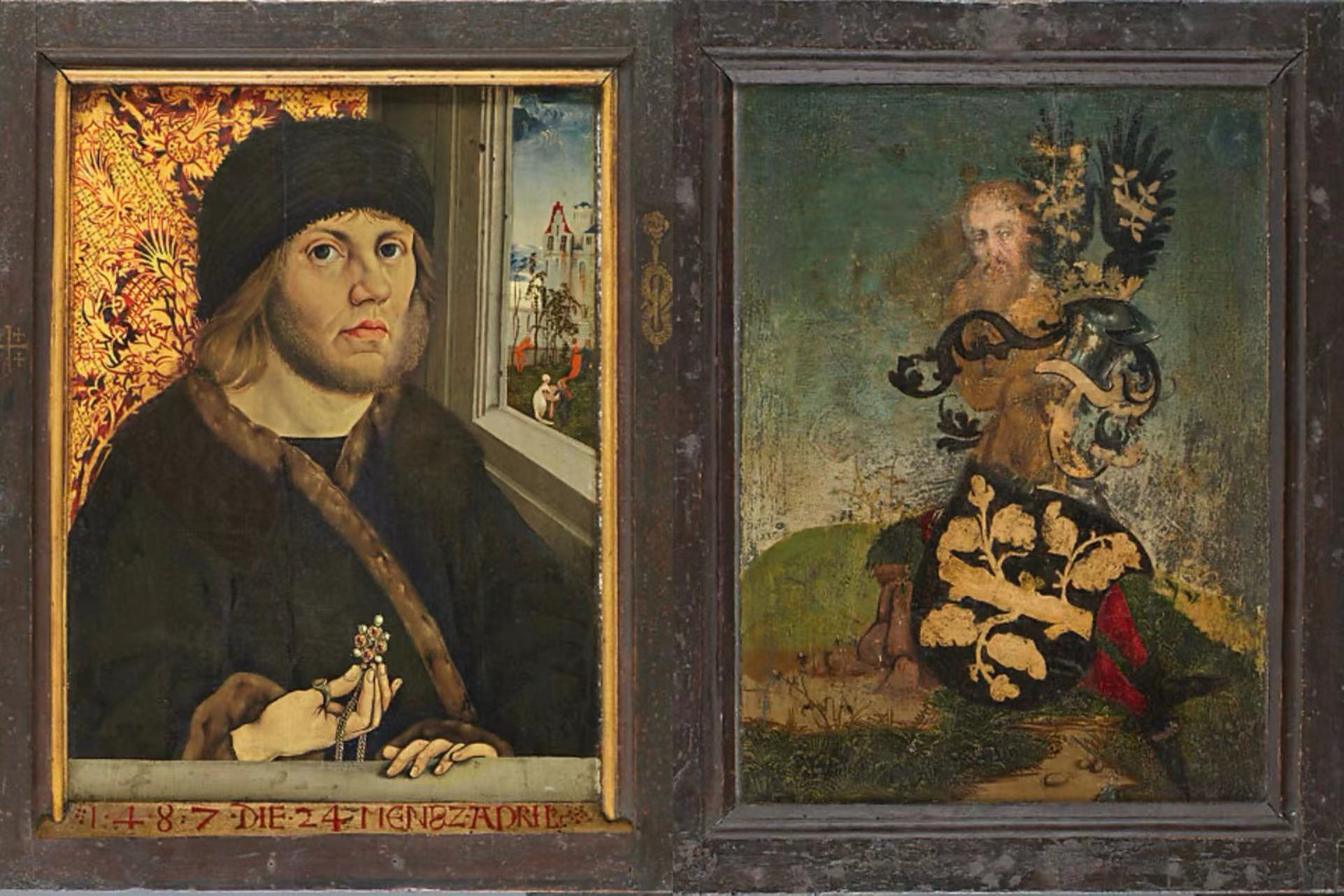

Wolfgang Beurer (Germany), Portrait of Johann von Reichen (left) and wild man with coat of arms on the back, 1487

Italian Covered Portrait

At the end of the 15th century, Italian multi-faceted portraits began to appear in large numbers, with covers and verso containing the same highly imaginative allegorical imagery as northern European portraits. Just as stylistic and technical innovations in painting spread north and south of the Alps, so too did the increasingly linguistic structures of portraiture and the symbolic imagery that accompanied them.

In addition to Florence, Venice, led by artists such as Jacometto Veneziano, Lorenzo Lotto, and Titian, flourished in a multifaceted portrait. From small wooden boxes to large canvas covers (a medium unique to Venice), portrait compositions combined the subject’s body with scenes and inscriptions from the Classical period, pairing them with celebrations of personal virtues (such as chastity) and of intellectual, moral, and social status.

The relationship between the cover and the work it concealed was often intentionally ambiguous, intended to provoke discussion among viewers. Lotto, who created covers for portraits and reliquaries throughout his career, expressed this vividly in 1524, advising his patron that “it will take the imagination to reveal [the meaning of the cover and the reverse]”.

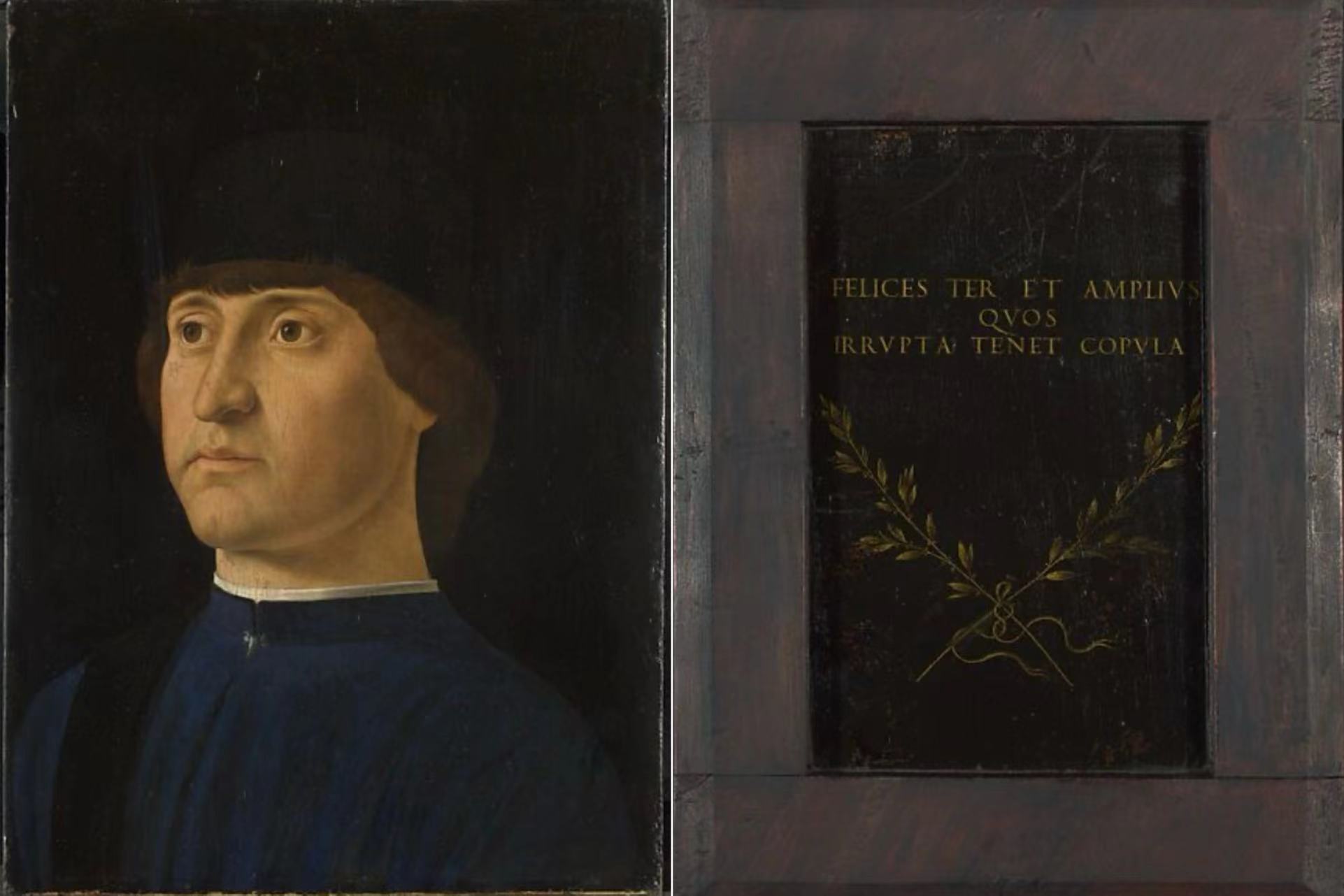

Jacometto (Italian, active in Venice), Portrait of a Man (probably Pietro Bembo) with a poem by Horace and a laurel branch tied to the reverse, ca. 1475-1497

Lorenzo Lotto (Italy), Cover with allegory, circa 1505

16th Century Nordic Portraiture

The double-sided and covered portraits produced in northern Europe in the first half of the sixteenth century continued the tradition established in the previous decades, with heraldry and allegory still the main forms of accompanying symbolic imagery.

In addition to wealthy merchants and bankers in German cities such as Nuremberg, Augsburg and Frankfurt, the Electors of Saxony were also important patrons of multifaceted portraits, whose functions varied from symbols of love to political propaganda.

This room offers a unique opportunity to view the reverse side of a portrait, which is often difficult to fully display. The reverse side images, often with symbolic and heraldic images, once played an important role in the presentation of the sitter, but are now partially obscured by the addition of collection information or by linings (wooden boards added in the 19th century to serve as structural support) during the collection process. For these reasons, as well as the complexity of display, the two-sided nature of many portraits remains little known.

Dürer (Nuremberg, Germany), Heraldry with Skull and Crossbones, 1503

Attributed to Ludger Tomlin the Younger (Germany), Portrait of a Woman with Sliding Cover; Sliding Portrait Cover, ca. 1560

Portable Portrait

Small portraits were often given as gifts for engagements, weddings, or travel as symbols of friendship, love, or political loyalty. These small portraits could be painted, decorated, painted, or carved in wood or wax and incorporated into boxes, gilded pendants, coins, and watches. These personal, intimate pieces were meant to be carried or worn on the body, often in a box or bag for easy transport.

The miniatures (round images in boxes) painted by German artists such as Lucas Cranach and Hans Holbein paralleled the development of miniature portraits in French and English courts beginning in the 1520s. The Protestant reformer Martin Luther took advantage of their dissemination by commissioning Lucas Cranach the Elder to create a number of small paired roundels of himself and his wife. These objects were placed in small wooden boxes and distributed as publicity material for the couple's controversial marriage in 1525.

Hans Holbein the Younger (Germany), Portrait of a Man in Imperial Uniform, 1532-1535

Lucas Cranach the Elder (Germany), Martin Luther and his Wife, 1525. Celebrating their union in a series of double-sided portraits in wooden cases.

Note: The exhibition will run until July 7. This article is compiled from Smithsonian magazine and the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition website.