Professor Rong Xinjiang of Peking University once gave a series of lectures entitled "Looking for Dunhuang all over the world" at the China National Silk Museum. Looking back on his experience of searching for Dunhuang treasures in Europe, America and Japan since 1985, in addition to academic content, there is also a lot of feelings during the visit. . After the series of lectures, a series of manuscripts were made based on the audio recordings, which were serialized in "Knowledge of Literature and History".

"Looking for Auspicious Lights and Feathers from All over the United States" is the last article in this series. It describes the author's search for Dunhuang collected in the United States by Yale University, Harvard University, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Metropolitan Museum, Princeton University, Freer Museum of Art, etc. , Turpan, Khotan documents and works of art experience and harvest.

The last lecture is about the Dunhuang, Turpan, and Khotan documents and artworks collected in the United States. The United States is a step slower than the old European colonial countries in terms of expeditions to the Western Regions. They do not have particularly large collections, but many universities and museums have successively collected some things, some of which are collected by the expedition team, and some are obtained through auction houses or donations. Very sporadic. Although the things are scattered and the collection is small, some of them are shining brightly, so I call the title of this lecture "Looking for the Auspicious Feathers Across the United States".

Rong Xinjiang

1. From Yale, Harvard to the Metropolitan Museum

The first time I went to the United States was from December 1996 to the spring of 1997. I participated in Yale University's "Regathering Treasures of Gaochang" project and stayed in the United States for three or four months. Centering on Yale University, I traveled along the east coast, from Boston to Washington, and investigated the collections of Yale University, Harvard University, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Metropolitan Museum, Princeton University, and the Library of Congress.

Yale University has the "Huntington Collection", which I knew from the beginning of my research in Khotan. Huntington (Ellsworth Huntington) is a teacher at Yale University, researching climate and geography. He went to Xinjiang for investigation in 1905, but his luck was not very good, or he did not have much experience in archaeology. He and Stein hired the same guide, but when he arrived at Dandan Ulik, the ruins were buried by wind and sand, and he only got a few small items. Huntington wrote "The Pulse of Asia", which is valuable for climate research and waterway analysis of the Tarim Basin.

The Huntington collection is partly in the Yale University Library (Yale University Library (Figure 1) and partly in the Yale University Archives. After I arrived at Yale University, I first went to the library and found some wooden slips in Khotanese and Khaluwen, as well as some Buddha statues, packed in kraft paper pockets. When the Buddha statues were taken out, the pockets were full of fallen sand. The library preserves cultural relics in the way of keeping books, but does not preserve cultural relics in the way of museums, which will cause great damage to cultural relics. I found a great deal of material about Huntington in the manuscript department and archives, including the correspondence of Bailey, Enmerik, and other text experts investigating his collection.

Figure 1 Yale University Library

Among the more important collections of Yale University is a painting of sackcloth banners unearthed in Bezeklik (Figure 2). Around 1932, this banner painting was sold by A. von Le Coq, with a serial number written by Le Coq on the back. Before World War II, the German economy was very poor. The museum decided to sell a batch of small cultural relics, mainly fine arts, which were sold by Le Coq. A very beautiful Manichean supporter is painted on the banner painting.

Figure 2 Manichaean flag painting on sackcloth unearthed in Bezeklik

Yale University also has a Dunhuang manuscript with an inscription on the third year of Sui Daye (607), and a Buddha statue painted on it is not in place, and it is fake at first glance. Inside the package was a note, which said that Mr. Duan Wenjie had come to see it, and said it was fake and of no value. However, the school can't just throw away the things that go into Tibet. There are a lot of such things in scattered works. I saw roughly the same manuscripts in several places, and they were probably sold collectively to make money. In the early years, Americans didn't read many real Dunhuang volumes, so it was easy to fall into the trap.

In December 1996, I went to the Sackler Museum at Harvard University with several Chinese teachers who were studying at Yale. Speaking of Harvard University, we must talk about Langdon Warner. Warner is a teacher of art history at Harvard University. From 1923 to 1924, Warner came to Dunhuang for the first time. He came late, and there were not many treasures left in the scripture cave, so he turned his idea to the murals, glued the murals off the wall piece by piece with sackcloth coated with adhesive, and then used water to remove the murals from the sackcloth . He stripped off more than ten pieces of fine Tang Dynasty murals in caves 335, 329, 321, and 320 of Mogao Grottoes, together with a painted statue of a Bodhisattva in cave 328, and plundered them back to the United States, where they were collected in the Fogg Art Museum of Harvard University. After the completion of the Sackler Museum, it was transferred from the Fogg Art Museum to the Sackler Museum. A Chinese translation of Warner's travelogue has been published. The title of the book is "On the Long Ancient Road in China". I asked someone to translate it, so I wrote a preface.

Wall paintings stripped by Warner, most notably the one in Cave 323. The north and south walls of Cave 323 are painted with paintings of Buddhist historical sites, depicting the stories of eight important Buddhist figures, including Kang Senghui, Fotucheng, and Master Tanyan. A Buddhist story adapted from Zhang Qian's historical facts. Warner stripped away the main part of the Eastern Jin Dynasty Yangdu Golden Statue Chuzhu Story Painting. Today, in front of the stripped mural in Cave 323, a photo taken from Harvard University was placed in front of it, and some publications put the stolen mural into the whole picture with a computer. Japanese scholar Mitsukazu Akiyama investigated and compared the stolen part with the existing wall, and found that the chemical potion used by Warner damaged the mural and made the mural black. In the book, Warner grandly stated that stripping the murals was to protect the murals. In fact, he destroyed the paint of the murals and the overall picture.

In 1925, Warner went to Dunhuang for the second time, and Peking University sent Mr. Chen Wanli to follow him. Warner's translator and Yanjing University student Wang Jinren participated in Warner's first Dunhuang expedition. Seeing that Warner had prepared a large amount of chemical potions and fabrics again this time, Wang Jinren secretly ran to the home of Hong Ye, the director of the History Department of Yenching University, to report. Hongye told the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Education notified the local officials in Gansu. After the vanguard of the Warner expedition arrived in Dunhuang, the local soldiers and civilians who had already heard the news did not allow the expedition to move the murals. Warner failed to enter the Mogao Grottoes for the second time, so he turned around and went to the Yulin Grottoes, and later wrote a small book "Wanfo Gorge: A Study of Buddhist Murals in the Ninth Century Grottoes", which is actually a long article.

Cave 328, taken by Warner, is the best first-class Dunhuang painted sculpture for Bodhisattvas. It turned out to be a pair, one was still in the cave, and the other was taken by Warner. He also took away some Buddha statues, scripture scrolls, and painted banners. In the 1920s, Warner could still get such good things. It can be seen that Taoist Wang and Dunhuang people hid a lot of things in their homes at that time.

There are also two relatively good silk paintings in the Sackler Museum of Harvard University, which may have been given to dignitaries by Taoist priests or local officials in Dunhuang in the early days. At that time, many officials sent to Xinjiang passed by Dunhuang. When local officials in Dunhuang encountered these demoted officials, they would treat them and give them gifts. Some of these officials returned to Beijing soon, and when they returned to their original posts, they were people who could talk in Beijing, so Dunhuang officials would send them the best things. One of the twelve-faced and six-armed Avalokitesvara Sutra paintings has an inscription dating from the second year of Song Yongxi (985). There is also a picture of Maitreya preaching, painted in the tenth year of Tianfu (945) in the later Jin Dynasty. These two silk paintings were donated to Harvard University by Grenville L. Winthrop in 1943, and both have individual research works and overall records. The silk painting was isolated from the outside air in the scripture cave. After more than a thousand years, the color is still good, but the color of the murals in the Mogao Grottoes is oxidized and distorted. When we study the colors of Dunhuang frescoes, we need to look more at the silk paintings with well-maintained colors. These paintings may be the first cultural relics brought out of the scripture cave, and they were scattered out very early. According to Stein's archaeological report, many silk paintings were placed on the upper floor of the scripture cave. Because Taoist Wang didn't understand the academic value of cultural relics, he picked things, mainly scrolls with good calligraphy. The best calligraphy is often ordinary Buddhist scriptures, which have the least academic value. However, Stein and Pelliot only selected non-Buddhist literature, Hu language literature, and silk paintings, and the documents they took with high academic value were precisely the ones that Wang Daoist did not want. This was the tragedy of the Chinese cultural circle at that time.

When I went to Harvard, I stopped by The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. There is a silk painting of Avalokitesvara unearthed in the Dunhuang Sutra Cave (975) in the eighth year of Kaibao in the Song Dynasty (Figure 3), which is an old collection of Duanfang. Duanfang was a great collector in the late Qing Dynasty and once served as the governor of Liangjiang. When I talked about the German collections, I mentioned that Duanfang expanded the monument of Qiequ Anzhou's meritorious deeds during his overseas trips. This silk painting has an inscription "Yan Jinqing sent from Lanzhou" by Wang Guan, a staff member of Duanfang. Wang Guan was a master of seal script in the late Qing Dynasty, and the Duanfang shogunate raised many such literati. Yan Jinqing, an official in Gansu Province, gave this silk painting to Duanfang. This silk painting has two time nodes. One is the inscription of the Song Kaibao’s offering for eight years, which is close to the time when the scripture cave was sealed; Arrived in Dunhuang in March 1907, and this painting fell into the hands of Duan Fang before Stein. Because of these two time points, this painting is of great significance for estimating the original situation of the scripture cave. The silk paintings are well preserved and have been collected and collected until now with bright colors. They are the fine works of the Dunhuang scripture cave. The black and white photo of this silk painting was published in the 59th issue of "Yilin Xunkan" on August 11, 1929. In order to collect materials on Dunhuang and Turpan, I once looked through magazines that may be related to Dunhuang and Turpan during the Republic of China, especially calligraphy magazines, which contain a lot of precious materials. "Yilin Xunkan" is a magazine of the Chinese Painting Research Association run by Jincheng, and has published many things related to Dunhuang. I used to read "Yilin Xunkan" in the library of Peking University. I could only read that page. Ten Weekly", I bought a copy, and it is convenient to turn it up.

Figure 3 Silk painting of Avalokitesvara in the Northern Song Dynasty in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (formerly in the collection of Duanfang)

I also had the opportunity to visit The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The China Pavilion here is most famous for the murals of the Yuan Dynasty at Guangsheng Temple in Shanxi. The entire mural is set on one wall of the exhibition hall of the China Pavilion. The museum's Dunhuang-Turpan collection includes some small Kizil murals acquired by the German expedition and Trinkler's Khotan collection. Later, due to lack of funds, the Trinkler expedition sold some of the cultural relics obtained. Most of the cultural relics are in the Overseas Museum in Bremen, Germany, and some were bought by several places such as the Metropolitan Museum of New York and the University of Tokyo. A member of our "Regathering Gaochang Treasures" project works in the Eastern Department of the Metropolitan Museum. She took me to the warehouse to look at these cultural relics. Most of them are small works of art. One of them is a statue of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva carved and printed during the Cao Yuanzhong period. . Dunhuang has many prints of this kind of veneer, some are real and some are fake, this one should be real.

2 Dunhuang and Turpan Documents in the Collection of Princeton University

In the Gest Library of Princeton University, I have a more important harvest. In January 1997, I went to Princeton University to visit Mr. Yu Yingshi, and at the same time, I went to the Gerster Library to investigate Dunhuang and Turpan documents. I learned very early on from the journals of the Gerster Library that there are a number of fragments of Dunhuang and Turpan documents in the library. In 2010, when my student Chen Huaiyu went to Princeton to study for a Ph.D., he compiled a catalog of these Dunhuang and Turpan documents. So this work is a relay, and the 1997 survey was the first step.

Where did the documents in the Princeton collection come from? Most of them were sold by Zhang Daqian to Luo Jimei, and Luo Jimei's wife sold them to Princeton University. Luo Jimei used to be the director of the photography department of "Central Daily". In the 1940s, she was invited by Chang Shuhong to take a lot of photos of Mogao Grottoes. These photos were also placed at Princeton University for research by scholars, and the copyright belongs to Mrs. Luo. When I was in Princeton, I looked through this set of photos. Luo Jimei’s photos are much more detailed than those of Stein and Pelliot. There are many partial pictures, and the costumes and crowns of the characters in the paintings can be clearly seen. Recently, Mr. Zhao Shengliang of the Dunhuang Academy helped Princeton organize and publish this set of photos, a total of nine volumes.

Zhang Daqian went to Dunhuang in May 1941, copied the murals of previous dynasties, renumbered the Mogao Grottoes, and obtained a batch of cultural relics. In the past, we thought that Zhang Daqian only had Dunhuang documents. Later, we saw dozens of Turpan documents with Zhang Daqian’s seal in the Gestalt library. They should have been bought by Zhang Daqian from a cultural relic vendor and then sold to Luo Jimei and his wife. This amount is considered a small and large-scale collection in the Turpan collection. I bought a batch of document photos from Mrs. Luo, and later distributed the photos to the students according to their majors for research in the Turpan document reading class I opened. For example, students who study archeology, I will give them photos of their clothes. This is a collection of clothing from the Gaochang County period. We know that there are very few clothing collections in the tombs of the Gaochang County period. This piece is of great research value.

There is a "Wucheng City in Gaochang County, Xizhou, Tang Dynasty, Going to Niling as a Bandit", which was issued by Gaochang County to the Wucheng City below. I used it in "New Views of the Official Documents of Khotan Local Military Town in the Tang Dynasty". this document. There are only seven lines left in the document, the second half of which is incomplete. It says that Tanren is the scouts of the Tang Dynasty who patrolled and scouted the enemy's situation in the Yingsuo area north of Turpan, which is the frontier area of the enemy. This document is only seven lines long, but it is written very visually.

There is another piece of "Tianbao Eight Years of Tianshan County 鸜鹆 Warehouse". Tianshan County is located in today's Tuokesun County, a county that must pass through from the Turpan Basin to southern Xinjiang. There is no record of this place in historical records, so these documents recording the operation of the local government are very precious.

There are still many fragments of documents in Princeton, for example, a few pieces can be sorted out to make a confession. The confession is the official certificate, and the date of release and the official position will be stamped with typesetting, and the typesetting will cover every word, so as to prevent the date or official position from being modified. The second article in the middle of this group of fragments reads "December 14th, the 23rd year of Kaiyuan", and the names of officials from the Zhongshu, Menxia, and Shangshu provinces of the Tang Dynasty are written in the latter few pieces. They are all high-ranking officials, some with names Seen in historical records.

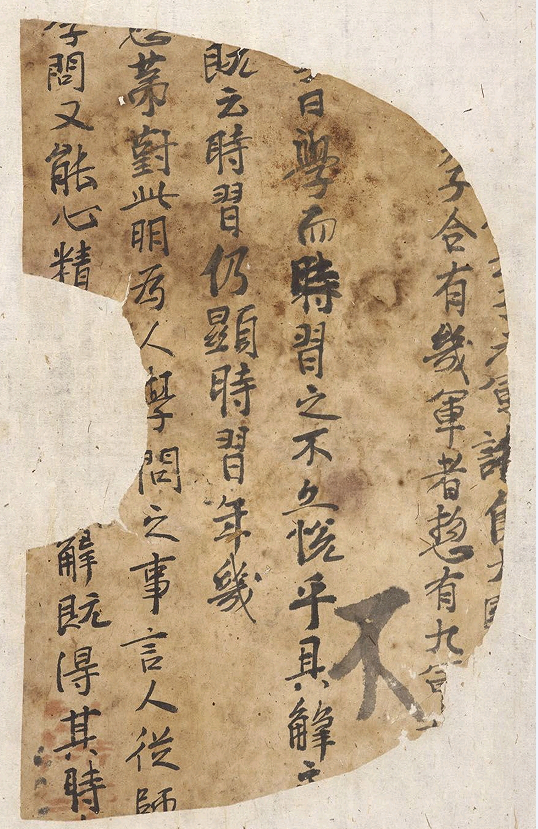

The most fragmented one is a group of Jingyice questionnaires (Figure 4), which are homework written by students in the Tang Dynasty. After students write the answer to a question, a piece is left for the teacher to write comments. The fine handwriting is written by the students, and the thick handwriting such as "right", "pass" and "although the notes are correct, there are many mistakes" are the teacher's comments. There are more than a dozen documents in this group, and the content involves classics such as "The Analects of Confucius", "Book of Filial Piety", and "Shangshu" that students of the Tang Dynasty studied. After these documents were discarded, the housewives used the waste to make soles or uppers, and to make funeral utensils. In fact, they are very vivid materials for studying the history of education in the Tang Dynasty. Teacher Liu Bo of the National Library of China wrote an article "Arranging and Researching the Fragments of the Tang Manuscripts of the Tang Manuscripts of the Turpan Manuscripts Collected by Princeton University" and made a research on this.

Figure 4 One of the Questionnaires for the Collection of Classics in the Gestalt Library

Part of the Princeton University collection was excavated by Zhang Daqian in the northern part of the Mogao Grottoes. He himself said that he picked it up by chance, but in fact he did excavations. I explained the whole story when I talked about the "Report of Zhang Junyi Xun" in "From Haneda Hiroshi Memorial Hall to Xingyu Bookstore". The northern area of Mogao Grottoes is the monk’s room cave where monks lived, the Zen cave where they practiced, the granary cave where they were stored, and the cave where people were buried. There are many burial objects in the upper cave, such as "Zhang Junyi's Announcement" is Zhang Junyi's burial object. After Mr. Peng Jinzhang arrived in Dunhuang, he excavated all the caves in the northern part of the Mogao Grottoes, cleared them down to the raw soil layer, and discovered a large number of documents from the Xixia and Yuan periods, including Uighur, Xixia, Tibetan, and Chinese. Yes, catalogs as large as octavo can be printed in several volumes. The burial objects in the Yu Grottoes were earlier, among which were found clothes with the year of Li Gui's Daliang regime written on them, dating from the end of the Sui Dynasty and the beginning of the Tang Dynasty, which are very precious. Caves 464 and 465, the northernmost ones in the North District, have three floors. The top floor was a printing office for printing Uyghur classics in the Yuan Dynasty. Later, the top floor collapsed, and the documents and wooden movable type collapsed to the middle floor. Stein and Pelliot made a rough excavation on it, and Pelliot took away more than one hundred wooden movable types. Zhang Daqian has been in Dunhuang for more than two years. Although he is not an archaeologist, he does excavate things from time to time. These Chinese documents, Uyghur documents (Figure 5) and many secular documents bear Zhang Daqian's seal, and it is certain that Zhang Daqian obtained them. Matsui Tai from Osaka University and Mr. Aydar from Xinjiang University have done related research.

Figure 5 Uyghur manuscripts unearthed in the northern part of the Mogao Grottoes in the Gestalt Library

There is a sackcloth sutra, the material is relatively poor, it is written "the eleventh", and the seal is "the seal of the king of Guashazhou", or "the seal of the great scripture of Guashazhou". There are two reading methods, and it can be confirmed that it is Dunhuang. It is very similar to the two linen scriptures collected by the Dunhuang Academy, which I mentioned in the footnotes of the article "The Nature of the Dunhuang Library Cave and the Reasons for its Closure".

I also went to the Art Museum of Princeton University. There are also some collections here, some of which are very good cultural relics from the Liao Dynasty, but the manuscript "Tao Te Ching" in its collection is a public case in the Dunhuang academic circle, and its authenticity is highly controversial. The document has the seal of "Dehua Li Shifan Jiangge Collection" and inscriptions of Huang Binhong and Ye Gongchuo. It was originally owned by Hong Kong collector Zhang Hong. When the writing paper was in Zhang Hong's hands, Ye Gongchuo told Jao Zongyi that there was something good in Zhang Hong's hands, you should study it. Mr. Rao wrote a long article, which was published in the "Oriental Culture" magazine of the University of Hong Kong. This is also Mr. Rao's first article on the study of Dunhuang manuscripts. When I was investigating Li Shengduo’s collection, I saw Mr. Zhou Jueliang write in an article: “At that time there was a certain Chen in Tianjin, who was said to be the nephew of Li Muzhai (Sheng Duo), who had seen the Dunhuang scrolls in Li’s collection. He is proficient in calligraphy, so he made a lot of fake things and sold them for money. I once saw a volume nearly ten feet long imitating Sui people's scriptures. Judging from the handwriting, the manuscript of the "Tao Te Ching" is also very likely to have been written by this gentleman." I quoted this account by Zhou Jueliang in the article "The Truth and False of the Dunhuang Scrolls Collected by Li Shengduo". Mr. Rao was skeptical after seeing the article, and later he did not include the article on the textual research of the "Tao Te Ching" in his Dunhuang essay collection.

At the end of the text of the cable manuscript "Tao Te Ching", it is inscribed "Jianheng second year, Gengyin, May 5th, Xinghuang County, Suoshu has been written", Jianheng is the year name of Sun Wu of the Three Kingdoms, which is earlier than all existing Dunhuang scrolls. After Princeton University bought it, Professor Frederick Mote published an article: The Oldest Chinese Book at Princeton. However, the academic circles have many opinions on its authenticity. It has two suspicious aspects. One is that it was signed in the second year of Jianheng. Dunhuang belonged to Cao Wei in the Three Kingdoms period, but it seems unreasonable that Dunhuang's Suo uses the year name of Sun Wu. The second is that the "Taishang Xuanyuan Tao Te Ching" was written in the article. "Laozi" was first listed as a Zishu, and it entered Taoism. It is as late as the Tang Dynasty, which does not match the second year of Jianheng. Some people also believe that this piece is genuine. An American scholar who studies Han Bamboo Slips suggested that the annotation of the requested copy of "Tao Te Ching" is very similar to the annotation of "Laozi" unearthed in Mawangdui, and this annotation is not found elsewhere. There are various views on this paper, and I will list them here.

The above is my harvest at Princeton University. After that, I went to the Library of Congress in Washington. When Mr. Wang Chongmin helped compile the catalog of rare books in the past, he described five or six volumes of Dunhuang manuscripts. Mr. S. Edgren, Director of the Gestalt Library and Chief Editor of the International Chinese Rare Book Bibliography Project at Princeton University, told me that the Library of Congress has since added some Dunhuang documents. I got the news and went to the Library of Congress. The person who received me was an old gentleman with a Chinese appearance. When he saw me, he jokingly said, "You came to look for the Dunhuang papers. Stein stole all the Dunhuang papers to London. How can we have them here?" In fact, they have some. , I saw a few pieces that time. Later, Mr. Li Xiaocong was invited by the Library of Congress to compile ancient Chinese maps in the collection. I asked him to find out if there are other scrolls besides the known Dunhuang documents. He found Ju Mi, director of the Chinese Department at the time, and Ju Mi gave me a set of photos. Among them, there are two scriptures that are relatively good, one from the Northern Wei Dynasty and one from the Tang Dynasty, and there are inscriptions and postscripts written by Luo Chunluo in the fourth year of the Republic of China. Luo Chunhao is a collector in Guangzhou, and many Dunhuang and Turpan scrolls contain his postscripts, such as the Beiguan Documents sold by a neighboring museum in Fujii, and the plain text collection of Xingyu Bookstore. These two pieces are ordinary scriptures, not of high text research value, but they are of certain significance for the study of Dunhuang literature diaspora.

Portrait of Princess Khotan in Three Freer Art Museum

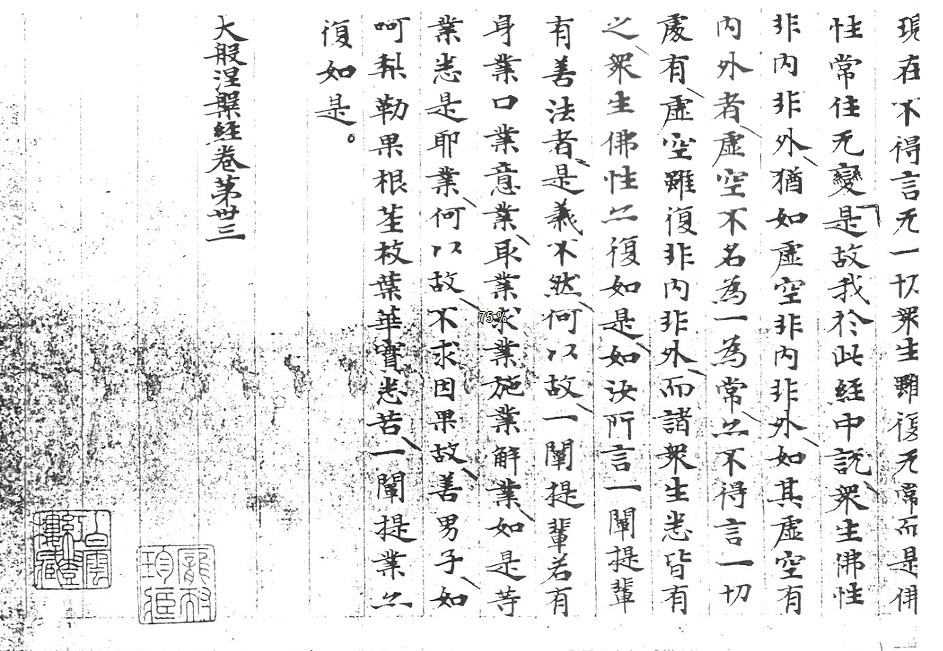

During our trip to Washington, we also went to The Freer Gallery of Art (Figure 6). The Freer Museum of Art and the Sackler Museum are a consortium that together form the National Museum of Asian Art. Zhang Zining of the Freer Art Museum received me, and he showed me a piece of "Mahaparinirvana Sutra" (Fig. 7) previously collected by Xu Chengyao, an official from Gansu Province in the Republic of China. Xu Chengyao is from Anhui. In the early years of the Republic of China, Zhang Guangjian, a native of Anhui, served as the governor of Gansu and recruited a group of Anhui officials to serve as officials in Gansu. These Anhui officials had some Dunhuang scrolls in their hands. Xu Chengyao was also Zhang Guangjian's subordinate. After he resigned and returned to Anhui, he turned to study Xiangbang literature and sold all the Dunhuang papers. Now the Anhui Museum has a batch of very good Dunhuang documents, which have not been published systematically.

Figure 6 Freer Art Museum

Figure 7 Volume 33 of "Mahaparinirvana Sutra" collected by Freer Art Museum

The Freer Art Museum also has a manuscript of the "Ten Kings Classic" written in Tibetan and Sichuan, with Weng Fanggang's inscription and postscript on it. It was scattered from the temple on Lushan Mountain, not from the Dunhuang scripture cave. I told Mr. Zhang this information, and later he went to the Freer Art Museum to sort out the "Ten Kings" and published it in "Dunhuang and Turpan Studies".

When I went to the Freer Museum of Art, the most important purpose was to investigate the silk paintings in Ye Changchi's old collection. Ye Changchi was a famous epigrapher in the late Qing Dynasty. From 1902 to 1906, he served as a scholar in Gansu Province. He toured various prefectures and counties in Gansu Province to test students and assess instructors. However, he did not go to Jiayuguan or Dunhuang County (now Dunhuang City) during his tour. ). If he arrived in Dunhuang, with the eyes of an epigrapher, he would be able to see the great value of the library cave documents at a glance, and the treasures of Dunhuang might not fall into the hands of foreigners. But then again, Pelliot saw a Dunhuang scroll in Urumqi, put down his original goal of Turpan, and went straight to Dunhuang. However, Chinese intellectuals were locked in their study rooms by the Qing Dynasty for three hundred years, and they lacked the enterprising spirit of Western archaeologists. Ye Changchi missed the scripture cave, firstly because he did not arrive in Dunhuang during his inspection tour, and secondly because Wang Zonghan, the county magistrate of Dunhuang, gave him wrong information. Wang Zonghan said that there were only a few hundred pieces in the Dunhuang scripture cave, and they were divided by Taoist priests, so there were not many left. In fact, this was a lie by Taoist Wang, and Ye Changchi believed it. The Chinese literati at that time lacked the spirit of today's archaeologists digging into the raw soil. Modern scholars, like me, search for Dunhuang all over the world, and try our best to get to the bottom of it.

Ye Changchi was a high-ranking official sent by the school, and the local officials and gentry in Gansu rushed to give him gifts. According to the "Diary of Yuandulu", on September 29, 1904, Dunhuang County Magistrate Wang Zonghan sent Ye Changchi a Song Dynasty silk painting and a scripture. The silk painting "Water Moon Avalokitesvara" has an inscription in the sixth year of Qiande (968). It is from the early Song Dynasty and belongs to the late period of the Sutra Cave. In the thirty-one pages of the Sutra, Ye Changchi's diary said it was in Sanskrit, but Ye Changchi didn't know Sanskrit. Judging from the fact that both Sanskrit scriptures and Khotanese scriptures found in Dunhuang are written in Brahma script, this may be Khotanese scriptures. Chinese intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century did not know about Khotanese, and may have mistaken Khotanese for Sanskrit. These thirty-one pages of scriptures are now missing. If found, it is possible to write a doctoral dissertation.

On October 13th of the same year, Wang Zonghai of Dunhuang presented Ye Changchi with specialties outside the Great Wall as a gift of fellowship, as well as two volumes of scriptures written by Tang people and a frame of portraits, all of which were found in Mogao Grottoes. Ye Changchi took away the calligraphy and paintings, but returned the souvenirs. One is the one hundred and one volumes of the "Great Prajna Sutra", which I don't know where it is now, and the other is the remnant of the "Kaiyi Sutra". The portrait depicts Nanwu Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva, Generals of the Five Paths, and Monk Daoming. Below it is a woman holding flowers. This "Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" enshrined by Princess Khotan is what I am looking for.

Ye Changchi sold his collection in his later years, and the two silk paintings belonged to Chuanshutang of Jiang Ruzao in Wuxing, Zhejiang. Jiang Ruzao hired Wang Guowei to compile a catalog of books. Wang Guowei wrote two postscripts to the two silk paintings, which were published in Volume 20 of "Guantang Jilin". According to Wang Guowei's postscript, the inscription on Qiande's six-year portrait is already incomplete. Ye Changchi's home was in poor preservation condition, rotted, and some words were incomplete. Now the most complete information about silk paintings is Ye Changchi's diary. In 1925, Jiang Ruzao sold his collection of books due to a loss in business, and two Dunhuang silk paintings entered into the owner of the Shanghai bookstore, Jin Songqing, and were bought by a Japanese in 1930. Who is the Japanese who bought the painting? It's from the Yamanaka Chamber of Commerce. "Water Moon Avalokitesvara" was published in American publications as early as 1953, indicating that it was collected in the Freer Art Museum, but "Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" has never been found.

I noticed "The Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" very early on. My first academic article, co-written with Mr. Zhang Guangda, was "About the State Name, Year, and Royal Lineage of the Khotan Kingdom in the Late Tang and Early Song Dynasties", which talked about this painting. We had never seen this painting at that time, but it was written according to Wang Guowei's postscript in "Guan Tang Ji Lin". I've always wanted to see this painting. I guess, since "Water Moon Avalokitesvara" is in the Freer Museum of Art, "Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" is likely to be there as well. In 1997, I finally had the opportunity to go to the Freer Art Museum. I copied a whole set of Ye Changchi’s diary, Wang Guowei’s postscript, and the records of Jin Songqing in Lanzhou Academic Journal, and showed it to Zhang Zining. He kept his composure and took me into the warehouse. First, I saw "Shuiyue Guanyin Statue". Some of the inscriptions were rotten and incomplete, but the overall protection was very good and the colors were very bright. Then look at the other part of the panel, and the "Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" is indeed there (Figure 8). According to the collection archives, the former was purchased from New York by the Freer Art Museum in 1930, and the Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva was purchased in 1935. The two paintings entered Freer at different times, but the general context is the same. Zhang Zining said that in the past, he did not dare to publish "Statue of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva" because the silk painting is very well preserved and very fresh. Many people who have seen it think it is fake.

Figure 8: The Princess of Khotan offering to the Bodhisattva of Ksitigarbha in the Freer Art Museum

According to my research, "Statue of Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha" is the latest silk painting in the scripture cave. The Kingdom of Khotan was called Jinyu Kingdom after 982 A.D. This painting was painted after the princess died, and it may be later. The scripture cave was closed at the beginning of the eleventh century, and this painting should be the latest painting. The fate between me and Princess Jinyu Guotian of Khotan originated from my first article, which was completed in 1982. In 1997, I finally saw the real face of this princess. I wrote in "Ye Changchi: The Pioneer of Dunhuang Studies": "'Princess' is safe and sound, and the color is as new, which makes people very excited."

This is the end of the story of searching for Dunhuang all over the world, thank you all.

(Additional note: "Looking for Dunhuang all over the world" is a manuscript compiled from audio recordings based on a series of lectures given by the China National Silk Museum. Thanks to the museum and the organizers for their excellent arrangements and careful work.)

[This article was originally published in Issue 8, 2023 of "Knowledge of Literature and History", published by The Paper with authorization]