The Paper has learned that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York is holding a major Mayan art exhibition - "The Life of the Gods: Divinity in Mayan Art" exhibiting nearly 100 treasures dating back to 250-900 AD.

From imposing stelae to trinkets carved from jade, shells, and obsidian, these rare artifacts unearthed from lost cities tell the stories of ancient Mayan gods and evoke a dynamic world of interconnected gods, people, and nature. world. “Maya artists inspired form to the gods through works of visual complexity and aesthetic refinement,” said Joanne Pillsbury, curator of ancient American art at the Met.

exhibition site

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, in partnership with the Kimbell Museum of Art in Fort Worth, documents the history and life of the Mayan culture during the Classic period (heyday, AD 250-900) through a variety of sculptures. With the natural decay and man-made destruction of almost all Mayan texts, the deciphering and analysis of the religious and spiritual life of the ancient Maya is mainly through cultural relics. Among the vessels and ornaments on display are some inscribed (or painted) hieroglyphs and images similar to extant Mayan codices.

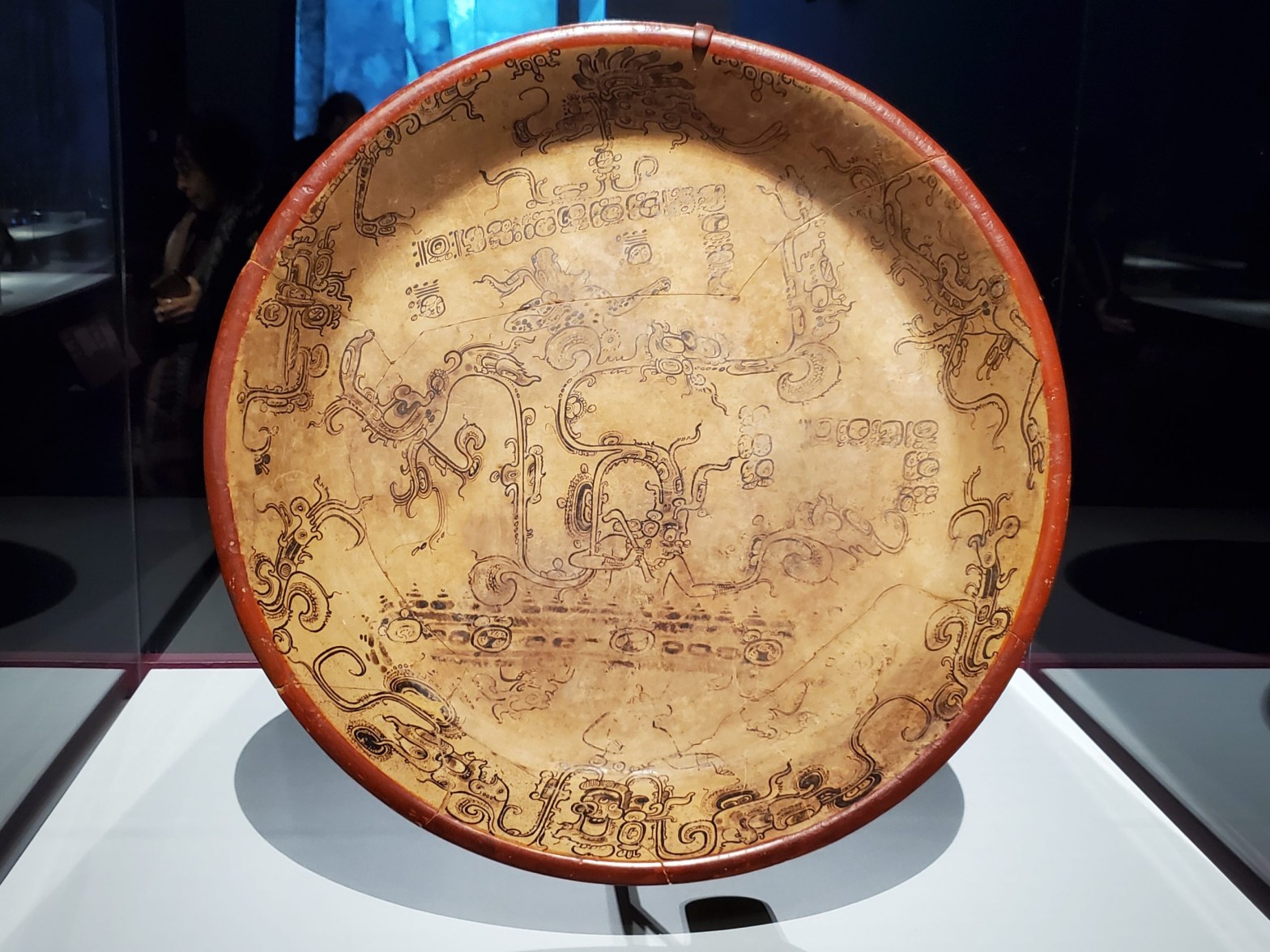

Plate of mythological scenes, 700-800 AD, with illustrations similar to Mayan codexes

In 250 AD, the Mayan civilization developed steadily. And in the next 600 years, hundreds of cities were established, and then developed into a number of city-states with intensive agriculture and concentrated cities. They carved stone tablets and described genealogies, war victories, and other achievements in hieroglyphics. Farmers cultivated border fields, terraced fields, and marsh paddy fields, and the food produced could support the surging population; artisans made artworks with flint, stone, bone horn, and shells, carved stone inscriptions, painted pottery, and murals; commodity trading flourished.

Beginning in the 9th century AD, the classical Mayan civilization began to decline. By the 10th century AD, the once-thriving Mayan cities were abandoned in the jungle.

Alligator whistle, 800 AD

In 1502, Columbus made his last voyage to the Americas. The ship docked in the Bay of Honduras, and Columbus and his crew set foot on the long-lost verdant land. In the local market, a kind of exquisitely crafted pottery basin from "Maya" attracted him. Since then, the magical name "Maya" was introduced to Europe for the first time. In 1519, the Spanish explorer Hernan Cortez led the Spanish army to sweep across Mexico. In the second half of the 16th century, Bishop Diego de Landa (1524-1579), the second governor of the Yucatan region, carried out military, religious and cultural suppression and colonization of the region.

"Many books that existed during the Classic period were probably destroyed by neglect centuries before Bishop Diego de Landa." Osvaldo, Yale University archaeologist and anthropologist, exhibition co-curator Oswaldo Chinchilla said, "The climate in the Maya region was particularly unfavorable to the preservation of organic materials. But the objects on display in the exhibition came from cities in ruins. The Spanish did not invade these ruins, which may be the reason for these sculptures and The reason for the preservation of the architectural structure."

Because there are few written records of the Maya's heyday, art historians, scholars, and the contemporary Mayan community gather information about the ancient civilization through the rare artworks and antiquities that survive. The Met divides the exhibit into seven sections—Creation, Day, Night, Rain, Corn, Knowledge, and Patronus.

The "Creation" section guides the audience back to the beginning of the world. At the entrance of the exhibition, there is a painted image on a square ceramic container. In the picture, an elderly god with jaguar ears sits on a throne covered with jaguar fur, presiding over the assembly of the gods. Relevant hieroglyphs record: On August 11, 3114 BC, 11 gods gathered in the square. Although what they discussed was unknown to humans, the mythical gathering is believed to have restored order to the world and created the conditions for the emergence of men, cities, and kingdoms.

Square vessel, Lo' Took' Akan (?) Xok (Mayan, active 8th century), Naranjo or surrounding area, northern Petén, Guatemala, 755-780

Mayan artists also enjoyed depicting humorous mythological episodes as a means of conveying profound meanings related to the origin of the gods, the world, humans, and social institutions. Itzamnaaj, the Mayan god of the sun, art, corn, and writing, in a vessel titled "Vessel with Mythological Scene." He had a protruding nose and was thought to be a peaceful old man) clumsily mounted on a wild boar. Like a scene in a modern comic book, there is a beautiful undulating line between his lips and his words, and he is asking passers-by about the whereabouts of the fugitives.

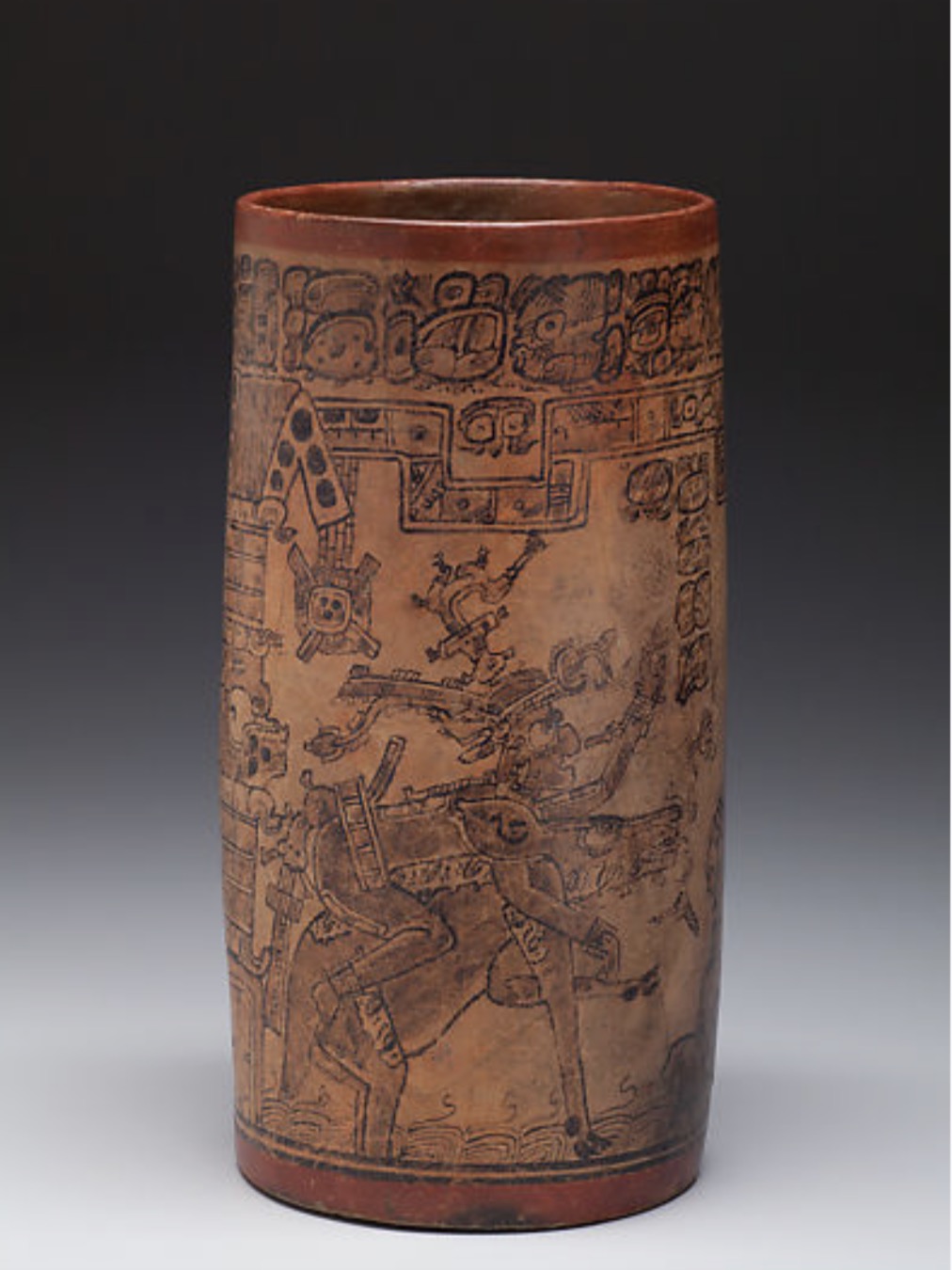

Vessels with mythological scenes, Mayan, Belize or Guatemala. 7th-8th century

Hieroglyphic block bearing the name Itzamnaaj, Maya, Tonina, Mexico, 7th-8th century, sandstone

The "Day" and "Night" sections of the exhibit focus on astrological symbolism and how animals became Mayan deities. As in many other religious systems, the sun and its associated deities, including the king "K'inich" (K'inich, king of Palenque, an important western city-state during the Classical Maya period), were the life-giving powers, while the moon represented a young Feminine, symbolizes reproduction and weaving. Jaguars, common nocturnal predators in Mesoamerica, are believed to be nocturnal deities with "aggressive, belligerent personalities." Many of these cultural relics are relief stone carvings, painted and inscribed ceramic vessels, or inscribed jade, obsidian and shells.

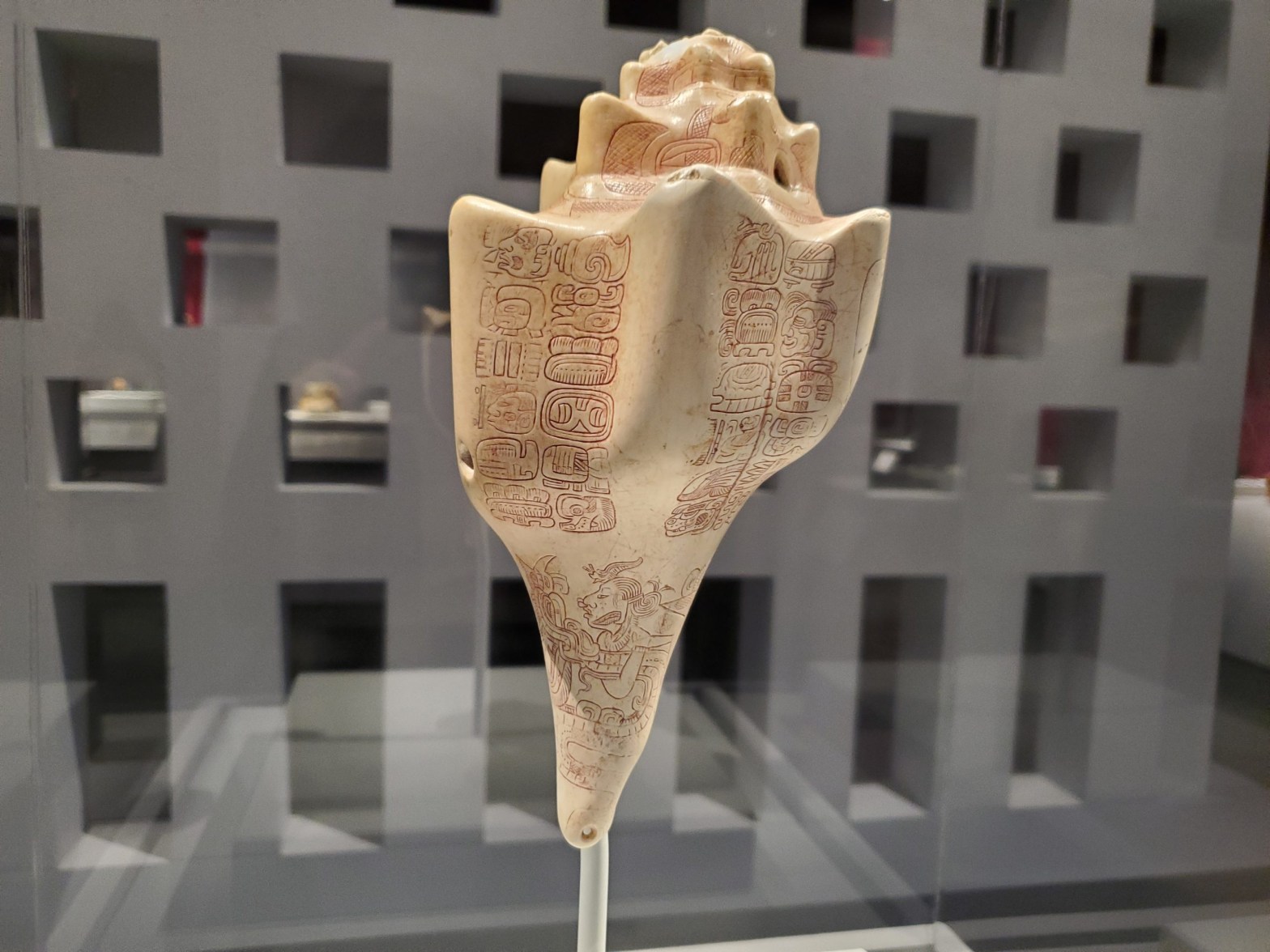

Conch trumpet, Maya, Petén Province, Guatemala, 4th-6th century, shell, hematite

In Mayan belief, objects were also living beings. The "Conch Trumpet" in the exhibition is made vivid by the way it can be viewed up and down: when the sharp corner is facing up, a face can be vaguely seen; when viewed in reverse, the inscription on it spells out the name of the object. The surface of the shell is engraved with two gods - the corn god and the sun god, who holds a snake in his arms.

Rabbit pendant, Maya, Guatemala, 4th-6th century

Rabbits are a recurring theme in Mayan art. As in Chinese mythology, rabbits were residents of the moon in Mayan culture and scheming liars. In an earthenware vessel, the goddess of the moon holds a rabbit and presides over a congregation of four lunas, possibly related to the phases of the moon. In court scenes, rabbits play the role of musicians or scribes.

Cylindrical vessel with Moon Goddess and other deities, Maya, Mexico or Guatemala, 7th-8th century

The "Rain" and "Corn" sections of the exhibit illuminate the relationship between the Maya and natural resources. Corn was a staple of the Mayan diet and economy, and the maize god was a particular fascination for ancient Mayan artists. They displayed multiple images of the maize god's birth, life, death, and rebirth in art form that may have coincided with the growing season to show reverence. The maize god is often depicted as a husked cob or the pistil of a flower, mostly in a swaying or dancing state, but in some figurines it is shown with arms folded and also has the function of whistling (when held against a long and An empty pole makes a high-pitched sound when blown).

Corn god coming from flowers, Maya, Mexico, 7th-9th century, ceramics, pigments

Some maize god sculptures present a slender body and handsome face, with the beauty of ripe corn. Long hair grows from the top of the head, reminiscent of corn silk. The jewels on his body set off his elegance and preciousness. He has flawless skin and is sometimes depicted as a baby, requiring constant attention and care. Failure to appease the corn god can lead to starvation in families and communities.

God of corn, Maya, Temple 22, Copan, Honduras, limestone

The exhibit also introduces the Mayan god of wind and rain, Chahk, and K'awiil, the god of lightning. K'awiil is easily recognizable by the ax on his forehead. In a bas-relief tablet bearing the names of carvers K'in Lakam Chahk and Jun Nat Omootz, an elegant lady appears to be conversing with the lightning god. The relief is thought to have once been part of the interior of the palace of Piedras Negras, one of the most powerful urban centers of Mayan Usumacinta.

Discussion with Royal Women, K'in Lakam Chahk, Jun Nat Omootz (Maya, active late 8th century). Usumacinta River area, 795, limestone

Many reliefs unearthed at the site bear the name of the sculptor, such as the unearthed throne also bears the signature of K'in Lakam Chahk. The throne presents a living mountain with the silhouettes of two figures in its eye. They were probably courtiers appearing in the text on the back of King K'inich Yat Ahk II and the throne. The text on the back also describes the king's enthronement in a complicated political situation, celebrating the dynasty he ruled. However, history didn't go the way the ruler wanted - the king was captured by rival lords from Yaxchilan in 808. Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan were abandoned shortly after this violent conflict in the early 9th century.

K'in Lakam Chahk, Patlajte' K'awiil Mo (Mayan, active 8th century) Throne with two kings in the eye of the mountain, Piedras Negras, Petén, Guatemala

It is worth noting that many works in the exhibition bear the artist's clear signature. "Archaeological information suggests that these artists were members of the royal court, creating for royal patrons and kings," Chinchilla said. "So, in some sites, archaeologists have found houses where scribes and artists lived, some very close to royal palaces. Researchers have also found tools in them, including conch shell inkpots. Some of them are remnants of what they used. Pigments that had been used in the process.” “Small axes used for carving were also found, along with mortars and pestles for grinding pigments.”

"Recent advances in the study of Mayan hieroglyphics have allowed us to identify the names of dozens of artists whose names appear for the first time on the labels of major exhibitions," the museum wrote in a statement. Artist signatures are rare in art, but Mayan sculptors and painters left their names on the beautifully carved stelae and decorative works they created."

The "Knowledge" and "Patron Saints" sections of the exhibition depict the relationship between the ancient ruling class and the Mayan gods. "As archaeologists make major discoveries that enrich our knowledge of classic Maya visual culture, this exhibition also demonstrates new understandings of the relationship between ancient communities and the sacred."

The exhibition site, followed by the "Dancing Macaw" video.

The exhibition also includes a film documenting a performance called "Dance of the Macaws." Originating in Santa Cruz, in the province of Verapaz, Guatemala, this dance involves young members of the community who wear ornate scarlet robes and decorative masks with hooked beaks that mimic the appearance of macaws. According to a description provided by the Metropolitan Museum, the dance illustrates "the origin of social institutions and the principles of religious ceremonies dedicated to the gods of the earth and mountains."

Note: This article is compiled from "HYPERALLERGIC", Smith Institution, Yale University websites, and the official website of the Metropolitan Museum. The exhibition will last until April 2, 2023.