The city of Babylon, the most well-known ancient city in the Mesopotamia. "Bible · Revelation" once said: "Babylon the Great, the mother of harlots and all abominations in the world." This evaluation once dominated the Western view of Babylon. After the 19th century, the development of modern archaeology has made people witness the remains from the city of Babylon: the complete "Code of Hammurabi", the 15-meter-high Ishtar Gate, the huge glazed brick painting The patterns of mythical beasts... These shocking cultural relics allow the world outside Babylon to gradually observe and watch the city from a new perspective.

The mysterious veil of Babylon City was slowly revealed.

City of Babylon and Kingdom of Babylon

Babylon city is located in the southern part of the Mesopotamia, more than 80 kilometers south of Baghdad, the capital of Iraq, and the Euphrates River flows through this city. Little is known about its origin. The earliest records about it date from the late third millennium BC (referring to 3000 BC-2001 BC). Compared with other ancient cities in the Mesopotamia, such as Elidu, Nippur, Uruk, Ur, etc., the construction time of this city is indeed a lot late. But once it rises, it becomes noticeable.

About 1894 BC, a tribe of Amorites occupied the city of Babylon. The chief of the tribe is Sumu-abum. His successor, Sumu-lael, annexed some of the surrounding small city-states and established an Amorite kingdom centered on the city of Babylon.

In 1792 BC, Hammurabi (reigned 1792-1750 BC), a descendant of Sumrael, ascended the throne. However, the kingdom of Babylon at that time was still a small country, extending 60 kilometers from the city of Babylon to the north and south, that is, to the border of the country.

In his early years in power, Hammurabi did not rush to annex neighboring countries, but instead used a complex strategy of alliances and anti-alliances among them. In the 29th year of his reign, he united the city-states of Yamhad and Mari in the north, defeated Elam in the east, and took control of the city-state of Eshnuna in the northeast, which was once occupied by Elam ( Eshnunna). In his 30th year in power, Hammurabi once again united with Mali in the north and sent troops to Larsa in the south, successfully annexing the city-state. At this time, according to the tradition of the Mesopotamia, Hammurabi called himself "the king of Sumer and Akkad". In his 32nd year in power, Hammurabi defeated Mali with a backhand and became the unrivaled overlord in the Mesopotamia. Therefore, he also called himself "the king of the four corners of the world".

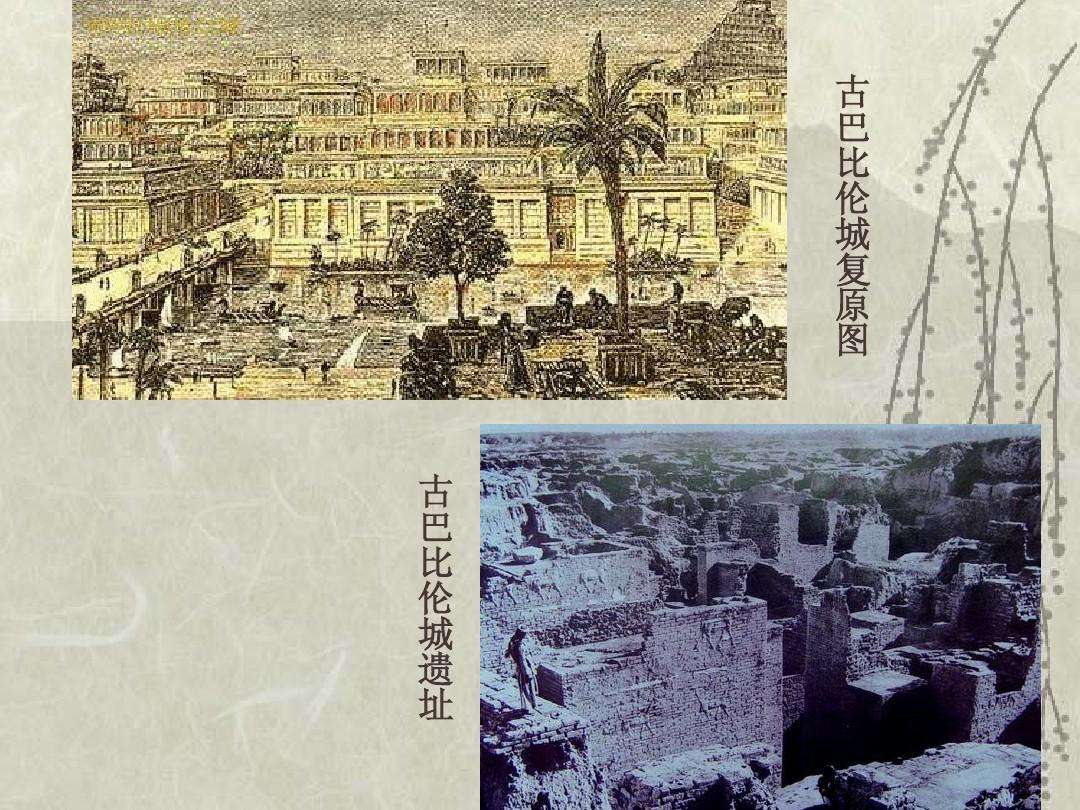

Restoration map and ruins of the ancient city of Babylon

Because the city of Babylon was the capital of the kingdom, the kingdom was later known as the Kingdom of Babylon (about 1894-1595 BC). The word "ancient" was added to distinguish another empire more than a thousand years later, the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 BC). In addition, the southern part of the two river basins ruled by this kingdom was also called Babylonia in later generations.

A splendid civilization was born during the period of the Babylonian Kingdom. For example, it deeply influenced later generations in terms of astronomy, calendar, mathematics, etc., and it also nourished the latecomers of the ancient Mesopotamia in terms of religion, mythology, art, literature, and language. And in Hammurabi's time, he carried out a series of reforms after fighting around: rebuilding cities destroyed by war or floods, housing displaced people, digging irrigation canals, promoting agricultural recovery, allowing clerics fleeing wars to rebuild gods temples, continued their belief in their gods, and enacted far-reaching laws.

These measures not only made the kingdom strong, but also left its mark on the capital city of Babylon. It's just that we know very little about the city's appearance at that time and the remains of cultural relics. The reason is that in the past few hundred years, the rise of the groundwater level has made it impossible to carry out underground archaeology for older and deeper layers. Therefore the appearance of Babylon in the second millennium BC and before is not known.

People's understanding of the city of Babylon in the Babylonian period comes from archaeological discoveries in other areas of the Mesopotamia, some from the manuscripts of ancient documents in later generations, and the remains of Babylon that were plundered to other cities due to wars. Most of these related materials are written information, and the remains of both documents and visual art effects, the most famous example is the stone column of the Code of Hammurabi.

stolen stone pillar

Robert Francis Harper, an important early Western Assyrian, recorded in detail the discovery process of the stone pillars in the Code of Hammurabi: From the end of 1901 to the beginning of 1902, an expedition sent by the French government to Iran , the stone pillars of the Code of Hammurabi were found in the Acropolis of the ancient Elamite capital of Susa. The stone pillar at that time broke into three pieces, but was easily put back together. The stone pillars are 225 cm high and made of black basalt. In addition, the expedition found other rubble engraved with the contents of the Codex. This shows that the Code of Hammurabi is not only engraved on this stone pillar, but also other stone pillars. The stone pillar was found in Susa because the king of Elam plundered it from the city of Babylon in the 12th century BC and brought it back to his capital as a trophy.

Above the front of the pillar is a set of bas-reliefs depicting Hammurabi standing in a pious manner before the sun god Shamash, while the sun god is sitting on a throne, seemingly conveying an oracle to the Babylonian king. Scholars at the Louvre believe that this scene represents God's legitimacy of Hammurabi's kingship and code.

The stone pillar of the Code of Hammurabi, black basalt, 225 cm high, hidden in the Louvre.

Below the reliefs are 16 columns of text, and on the back of the stone pillars are 28 columns. The content of the code is divided into three parts: the preamble, the main body and the conclusion. In the preface, Hammurabi describes his conquest of the Quartet and his devout construction of the capital. He became the Chosen King and the Just King.

The second part clarifies 275 to 300 legal provisions. These articles all have a similar narrative format, that one person's actions lead to corresponding consequences. The articles cover a wide range of areas, including perjury, theft, labor, family affairs and personal assault. Among them, the "homogenous revenge law" is the most well-known, that is, the principle of "a tooth for a tooth and an eye for an eye". This principle is similarly stated in later Bibles.

The third part emphasizes the unshakable future of the code in poetic form. "The Code was issued as a divine decree, for the benefit of mankind to be treated justly. The Code is vivid and acerbic against any future ruler who dares to tamper with it: His cities shall perish, the people shall be scattered, and the kingdom shall be replaced. , his name will be forgotten forever...his soul (in hell) has no water to drink."

From the code, one can know the stratification of Babylonian society at that time, namely nobles, commoners and slaves. Victims of different classes receive different compensation. The nobles were protected by the law of homomorphic revenge, while the lower classes could only receive financial compensation.

This code is valid throughout the Babylonian kingdom. It creates a bond between all classes of people, and sets norms for society in terms of morality, social class, gender relations, and religious beliefs. At the same time, it also established the absolute authority of the king in the country.

Some scholars cite what is mentioned in the Codex, and believe that the stone pillar stands in front of the statue of Hammurabi in the capital city of Babylon; some scholars believe that the stone pillar stands in a solemn place such as a temple. In any case, the writing of the code on the stone pillar is a declaration made by the king, that is, the justice that he brings to his subjects as the chosen king. Perhaps this stone pillar has also become a symbol - "symbolizing the concept of justice based on kingship and legal procedures in the Mesopotamia."

The impact of this code is far-reaching. Clay tablets containing parts of the Codex appeared in the libraries of the Assyrian Empire a thousand years later. Although the Mesopotamia suffered successive conquests by Persian, Greek and Parthian empires starting in the 6th century BC, parts of this code were still used. Outside the Mesopotamia, the influence of the Code of Hammurabi also exists. Even today, in the Chamber of the House of Representatives of the United States Capitol, there are 23 reliefs of historical figures who have a major influence on the foundation of American legislation, including Hammurabi.

The city of Babylon that changed hands several times

In 1595 BC, Babylon was invaded by Hittites from the northern Anatolian plateau (in present-day Turkey), the descendants of Hammurabi failed to defend against the enemy, and the dynasty perished. Later, the Kassites from the Zagros Mountains in the east of the two rivers infiltrated, occupied the city of Babylon, and established the Kassites Dynasty (1595-1155 BC). This dynasty lasted for more than 400 years, inherited the religion and traditions of Babylon, and also left cultural relics such as monuments and cylinder seals showing the images of the gods in the two rivers.

The city of Babylon changed hands several times after that. It was ruled by the Assyrians and sacked by the Elamites until it became part of the expanding Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BC. During this constant political upheaval, the continued development of the city of Babylon was interrupted, and the remains that remained in the strata often exhibited dramatic changes. But in any case, since the Babylonian period, until around the 4th century BC, the city of Babylon was an important political center in the southern Mesopotamia.

During this time, many kings were in awe of Babylonian temples and erected monuments in them in an attempt to gain legitimacy and show their glory. But there were also rulers who plundered their wealth or punished the Babylonians for their rebellion. A prominent example is the Assyrian king Sennacherib (reigned 704-681 BC). At that time, in the face of the control of the Assyrian Empire, protests often broke out in the southern part of the Mesopotamia, that is, in the Babylonian region. Because Sinaherib failed to effectively control the situation, he turned his anger on the city of Babylon. In 689 B.C.E., he recorded his revenge against the city of Babylon: razing buildings to the ground and throwing rubble into the river as if a flood washed the face of the earth. But the king's successors were ashamed to talk about the man-made destruction of Babylon as blasphemous. They only downplayed it as a natural disaster.

However, the catastrophe encountered in the city gave the opportunity to rebuild the city of Babylon by a new dynasty soon after, which was the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Metropolis during the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire was rebuilt on the basis of the original city plan and the architecture of the late Assyrian Empire. Judging from the remains of the Babylonian city that have been excavated so far, "It is true that no royal or temple buildings earlier than the late Syrian Empire have been found, and as a result of large-scale reconstruction, the ruins of temples, palaces and city walls are mainly from the Neo-Babylonian period. ."

The city of Babylon is very large, nearly 900 hectares, and was the largest city in the ancient Mesopotamia. It borders the east bank of the Euphrates, and its outline resembles a large triangle: one side is the Euphrates, and the other two are the outer city walls with moats. The outer city wall is 18 kilometers long. According to the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, the wall was 25 meters wide and could accommodate four-horse chariots driving on it. After modern archaeological excavations, scholars believe that the city wall is a double wall, the height of the inner wall and the outer wall is more than 5 meters, and its width is more than 7 meters. There is also a 12-meter-wide gap between the two walls, filled with gravel or rubble, the height of which reaches the top of the city wall. It can be seen that Herodotus's statement is not an exaggeration. Such a city wall must have been breathtaking in the eyes of the people at that time, and it was also selected into the original version of the Seven Wonders of the World.

In the city of Babylon, there is also a rectangular inner city. Part of the inner city extends to the west bank of the Euphrates, and is connected to the inner city on the east bank by bridges. In the inner city, there are the temples of Esagila and Etemenanki dedicated to the patron saint of Babylon, Marduk. The inner city is also surrounded by walls and has 8 entrances and exits. The largest of these is the Ishtar Gate on the north side of the inner city. Its builder was the famous Nebuchadnezzar II (604-562 BC). He is known as the greatest builder of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

The Ishtar Gate is a compound city gate, one of which is preserved in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, Germany. At the beginning of the 20th century, when German archaeologists conducted archaeological excavations in the city of Babylon, they were amazed at the towering, majestic and ornate decoration of the city gate, and they moved the city gate to Germany. Today, the 15-meter-high Ishtar Gate stands in the Pergamon Museum. The other part of the city gate on the original site of Babylon is also 12 meters high, and its original height may be higher.

The restored Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum, Germany

The blue-toned glazed tiles of the Ishtar Gate are decorated with reliefs of two remarkable animals - the Mušḫuššu dragon and the bull. Both animals represented gods in Babylonian religion at the time: the serpent dragon symbolized Marduk, the chief god of Babylon, and the bull represented Adad, the weather god. The horizontal floral arrangement at the bottom of the gate may represent Ishtar, the god of war and love.

The snake dragon is a combination of various creatures: it has the head, neck, and tail of a snake, and it sticks out its tongue like a snake; it has the front paws of a lion, the hind legs of a bird, and scales on its body; its head has horns and a tail. The tip also has the sting of a scorpion. The snake dragon moved forward with its head held high and its tail raised. The Marduk it symbolized was originally just the protector of Babylon and the god of agriculture, and developed into the god of the state and the main god of the Babylonian gods during the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Serpent dragon image on the Ishtar gate

In the past, the buildings in the Mesopotamia mainly used adobe and fired bricks. In the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, although the same was true, "fired bricks were used more and more in the superstructure of palace buildings, creating dazzling glazes for Neo-Babylonian craftsmen. Technology makes it possible."

These glazed tiles were used to decorate the Ishtar Gate as well as the walls of the palace and the sides of important roads. Special patterns, such as animals and plants, geometric patterns, etc., need to be designed in advance on the brick, and then glazed and fired. The snake dragon and bull are orange or white, set off against the background of lapis lazuli-like dark blue glazed tiles, which is more prominent and solemn.

On the wall on one side of the city gate, the glazed tiles are inscribed with this inscription: "I (Nebuchadnezzar) rooted the foundation of the city gate to the water table. I built the city gate with pure blue stone. On the inner wall of the city gate are bulls and dragons. I decorate them grandly with gorgeous colors, so that everyone can stare with breathless awe."

Entering the inner city from the Ishtar Gate, people will walk on the straight parade avenue, leading directly to the core of the inner city - the Temple of Marduk. During the Babylonian New Years (around the vernal equinox), this avenue is the holy way, and people carry a statue of the god Marduk into the temple. At the same time, this gate is also the gate of the king. The king passes through this gate and reaffirms the kingship under the blessing of God.

Model of the Parade Boulevard and Ishtar Gate by the Pergamon Museum, Germany

From 1899 to 1917, the German archaeological team excavated a 250-meter long parade avenue. The 180-meter avenue is lined with glazed brick paintings, the style and tone of which are the same as the Ishtar Gate, except that the animals are replaced by lions. In Babylonian religion, the lion represented the goddess Ishtar.

The Pergamon Museum has restored some of the relief decorations on the parade avenue, which is 30 meters long and 8 meters wide. The avenue on the original site was 20-24 meters wide.

The glazed brick decorations on both sides of the restored parade avenue in the Pergamon Museum are decorated with lions, symbolizing the god Ishtar

The prominence of these three animal images probably not only shows Nebuchadnezzar II's reverence for the gods, but he may also hope that these animals blessed by divine power can protect the city of Babylon. 26 At the same time, protect yourself and deter the enemy.

Regarding the city of Babylon, many people also think of the Hanging Gardens. However, people have not found the exact corresponding relics. Some scholars even believe that the Hanging Gardens are not in Babylon, but in Nineveh, Assyria. It is traditionally believed that the Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was built by Nebuchadnezzar II for his wife Amytis from the Kingdom of Media to comfort her in her homesickness for the mountains and rivers.

unique city

During the time of Nebuchadnezzar II, the city of Babylon reached its peak and became the largest city in the world at that time. Michael Seymour, an expert on the ancient Near East at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said in an article that Nebuchadnezzar continued the Assyrian tradition of moving large numbers of people from one part of the empire to another. The purpose may be to avoid breeding potential centers of resistance, or to mobilize the workforce. It is also from this that his similar actions against the western kingdom of Judah and the city of Jerusalem, the famous "Babylonian prisoner", earned the king a bad name in the Bible. As a result, Babylon became synonymous with evil, decadence, a land of sin, and was prophesied to be overthrown at the hands of God's vengeance. But the Babylonian kings positioned themselves as devout believers and repeatedly emphasized this piety in the form of inscriptions when rebuilding the temple. However, the God they believe in is not Jehovah.

In addition, in the eyes of Christians in the past, the city was extremely arrogant, because the Bible records that the Babylonians tried to build a high tower so that "the top of the tower would reach the sky." This caused the dissatisfaction of the LORD, so he "confused the words of the people there, and scattered the people over the whole earth, so the name of the city was Babel (babel, which means 'confusion')."

In Jewish Hebrew, Babylon is called "Babel". The name "Babylon" comes from the Greek translation of the Jewish classics - the Hebrew Bible (the same content as the Christian "Bible · Old Testament"). But in the eyes of the Babylonians, their capital city has had its own name since the Sumerian civilization, called "God's Gate", and this meaning runs through the entire history of Babylon.

In 539 BC, the first Persian Empire occupied the city of Babylon; two hundred years later, Alexander the Great came to Babylon; not long after, the city became part of the Seleucid dynasty. Since then, Babylon's status has been declining. In the 2nd century BC, Babylon was occupied by the Parthian Empire, and its art was influenced by Greek styles. Although the vicinity of the city of Babylon was still settled later, its glorious history is gone, and even the bricks of its ancient buildings were removed by the people to build houses. On those bricks, from time to time, there are inscriptions printed by Nebuchadnezzar II.

After more than 2,000 years of prosperity, the city of Babylon has fallen, and the ruins left behind have returned to their original colors. Today, although the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon are still spectacular and listed among the World Heritage Sites, the appearance of Babylon that we can see is limited after all, and more are still buried under the soil and covered with a thick veil of mystery. At the same time, these relics are often intertwined with myths and legends and become a unique label for the city of Babylon.

In different eras, people with different ethnic, religious and cultural backgrounds had different impressions of Babylon. Which is closer to the true face of history? It's hard to answer. In other words, it is difficult to have a unified answer. Perhaps that is why the city of Babylon has such enduring appeal.