Recently, a symposium on the publication of Criticism of Pure Reason (translated by Han Linhe) was held at the Commercial Press. The conference was hosted by the Commercial Press, the Institute of Foreign Philosophy of Peking University, the Department of Foreign Philosophy of Peking University and the Chinese Kant Society.

Kant is one of the most important and far-reaching philosophers in the West, and has a foundational significance for modern Western thought. Kant's philosophical achievements are concentrated in the "Three Criticisms". His "Three Criticisms" are "Critique of Pure Reason", which mainly solves epistemological problems, "Critique of Practical Reason", which mainly solves problems of moral philosophy, and "Critique of Judgment", which mainly solves aesthetic problems. The "Three Criticisms" touch on It captures the knowledge, emotion, and will of the subjective world of human beings. The Critique of Pure Reason is the core of Kant's philosophy. The Critique of Pure Reason discusses the universal cognitive ability of human beings, which transcends the barriers of civilization and is valued in many parts of the world.

The Critique of Pure Reason, newly published by the Commercial Press, was translated by Professor Han Linhe from the Institute of Foreign Philosophy and Department of Philosophy of Peking University. Han Linhe is a well-known analytic philosopher and an expert on Wittgenstein studies. He has presided over the translation of the 8-volume "Works of Wittgenstein". He has been focusing on the study of Kant's philosophy for many years.

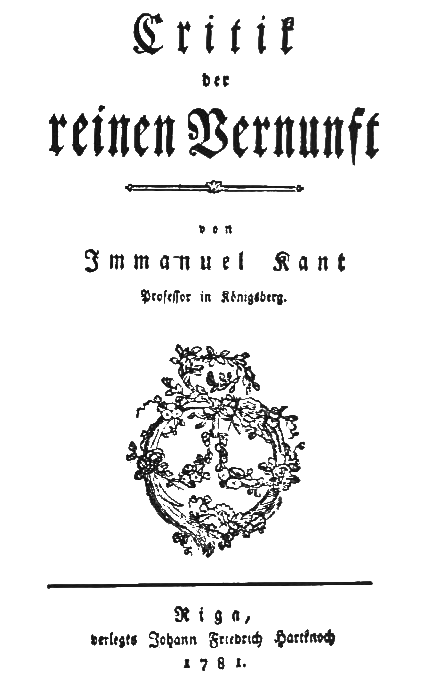

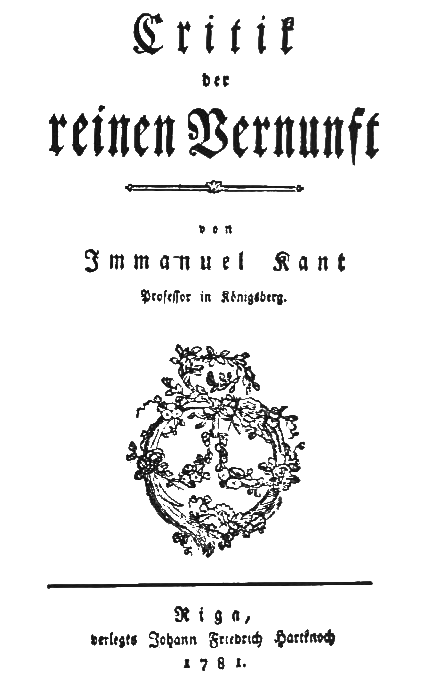

Regarding the choice of translation bases, Han Linhe introduced that the first edition (often called "A edition") of Critique of Pure Reason was published in 1781, and the second edition (often called "B edition") was published in 1787. Thereafter, before Kant's death, the third to fifth editions were published successively in 1790, 1794 and 1799. In 1818 and 1828, the sixth and seventh editions were published. Of these editions, only the first and second editions were modified by Kant himself, who also actively participated in the publication process. The third through seventh editions are basically reprints of the original second edition (with two additional pages of Grillo's corrections at the end of the fifth edition). According to scholars' research, Kant did not participate in the publishing process of the third to fifth editions.

It is understood that there are at least 10 English translations and at least 12 Japanese translations of Critique of Pure Reason.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a classic that is constantly translated and new, and every retranslation is a new interpretation of Kant's philosophy. There are now seven "full" translations published in the Chinese world. The first Chinese translation published in 1931, the Hu Renyuan version, was translated from the Müller version. The Lan Gongwu translation published in 1957 (translated from 1933 to 1935) was translated from Smith's translation. Mou Zongsan's version and Wei Zhuomin's version, published in 1983 and 1991 respectively, were also translated from this version. Deng Xiaomang's translation published in 2004 is based on the Schmidt edition reprinted in 1976. Li Qiuling's translation published in the same year was based on the Academy's version. The Wang Jiuxing (main) translation published in 2018 was also translated based on the Academy Edition (this translation is not a full translation in the strict sense, because it lacks the most important chapter of the book, that is, the part about the transcendental deduction of categories).

Regarding his new translation, Han Linhe introduced that he borrowed the methods of organizing and commenting on ancient Chinese books and gave a research commentary of nearly 100,000 words. These annotations include: analyzing multiple editions, examining typographical and typographical errors in historical editions; discovering and correcting Kant's own clerical errors; prompting German text editors and English translators to modify some key words, and Different understandings and possible misunderstandings caused by these factors; I carefully studied the terms referred to by pronouns in the text, and listed and compared the controversial parts; I tried to determine some popular Chinese Kant terms to explain different translators Reasons for using different translations.

Because Han Linhe has both the British empiricism and the academic background of contemporary logic and analytic philosophy, there are some places in the annotations that indicate the ideological origin of the concepts used by Kant and the inspiration for later generations. These works can help readers to grasp the Critique of Pure Reason more deeply, and also provide a contemporary philosophical perspective for German classical philosophy. During the seminar, Wang Bo, vice president of Peking University, pointed out that the Critique of Pure Reason translated by Han Linhe is the eighth Chinese translation. The Chinese world needs to overcome the barriers of language and time to understand Western culture. The sense of language is connected with our breath. Li Qiuling, an expert in Kant research and the translator of the Chinese version of the Complete Works of Kant, said that translating academic works is not simply a matter of language conversion, but requires in-depth research and the accumulation of predecessors. Han Linhe's new translation balances many conventional terms in the academic world, and also gives detailed annotations, indicating the source of some key words in different versions and translations, giving readers a lot of convenience. Xie Dikun, an expert on Kant studies, pointed out that translating Kant's classical philosophy from the perspective of analytical philosophy has unique methodologies. The footnotes in the book are also impressive.

During the seminar, Wang Bo, vice president of Peking University, pointed out that the Critique of Pure Reason translated by Han Linhe is the eighth Chinese translation. The Chinese world needs to overcome the barriers of language and time to understand Western culture. The sense of language is connected with our breath. Li Qiuling, an expert in Kant research and the translator of the Chinese version of the Complete Works of Kant, said that translating academic works is not simply a matter of language conversion, but requires in-depth research and the accumulation of predecessors. Han Linhe's new translation balances many conventional terms in the academic world, and also gives detailed annotations, indicating the source of some key words in different versions and translations, giving readers a lot of convenience. Xie Dikun, an expert on Kant studies, pointed out that translating Kant's classical philosophy from the perspective of analytical philosophy has unique methodologies. The footnotes in the book are also impressive.

It is reported that the Critique of Pure Reason, as Kant's "first critique", starts from the understanding of why it is possible, criticizes and sublates rationalism and empiricism, and believes that there are two sources of human knowledge: one is provided by human senses Acquired perception experience; one is the innate form and category in human thinking that brings inevitability and universality to knowledge, and is an "innate comprehensive judgment" applicable to the phenomenal world. The main discussion in the book revolves around "innate comprehensive judgment".

"Innate comprehensive judgment" is not difficult to understand. It refers to a kind of judgment that is universal, inevitable, and can provide real knowledge. The difficulty lies in "how is the innate comprehensive judgment possible". This question concerns the process of how innate knowledge forms and empirical knowledge matter constitute knowledge. Kant's transcendental self provides the a priori form of knowledge, thus ensuring the universal inevitability of knowledge; his thing-in-itself provides the material of experience, enabling us to continuously acquire new knowledge content. Kant decomposes the core question of "how is a priori synthetic judgment possible" into four questions, namely, how is pure mathematics possible? How is pure natural science possible? How is metaphysics as a natural inclination possible? How is metaphysics as a science possible?

In his discussion of these issues, Kant pointed out that the subjective (transcendental self) provides the form of knowledge, and the objective (the thing-in-itself) provides the material of knowledge, and the combination of the two constitutes empirical knowledge or knowledge with both universal inevitability and new content. Scientific knowledge, which is the basic principle behind the possibility of a priori comprehensive judgment. Kant's entire epistemology is mainly divided into three steps: sensibility, intellect, and reason to illustrate how the two are combined.

More subversive in the perceptual stage is Kant's view of time and space. The transcendental self provides an innate form of intuition for our cognition, which is time and space, and it is through these two forms of intuition that we form our perceptual cognition of phenomena. Kant believes that time and space are not the existence forms of objective things themselves, but a form of subjective cognition of the objects we feel. Kant believes that space is the form of external senses, that is, the innate form of intuition about all external phenomena; time is the form of inner senses, that is, the innate form of intuition of all internal phenomena (inner state).

The intellectual stage also has some innate forms of knowledge, that is, "innate thinking forms", which are expressed in twelve categories, namely singularity, plurality, and totality; reality, negation, and limitation; substance and accident, Cause and effect, active and passive; possibility and impossibility, existence and non-existence, inevitability and contingency. The cognitive activity in the intellectual stage is to use these categories to synthesize and unify the phenomena that are already in space and time. By adding these twelve categories to different phenomena, empirical knowledge or scientific knowledge with universal and inevitable connection is formed.

In the perceptual stage, we endow the perceptual material with the innate intuitive forms (space and time), form phenomena, and produce mathematical knowledge; in the intellectual stage, we use the innate thinking forms (categories) to synthesize the phenomena that have been formed in the perceptual stage unification, resulting in natural scientific knowledge. Entering a higher level of "rationality" requires a transition from the specific knowledge of the intellect to the more complete absolute knowledge. For example, go further from specific psychological knowledge to knowledge about the "soul" itself, and from specific physics knowledge to knowledge about the "universe" as a whole.

Kant is one of the most important and far-reaching philosophers in the West, and has a foundational significance for modern Western thought. Kant's philosophical achievements are concentrated in the "Three Criticisms". His "Three Criticisms" are "Critique of Pure Reason", which mainly solves epistemological problems, "Critique of Practical Reason", which mainly solves problems of moral philosophy, and "Critique of Judgment", which mainly solves aesthetic problems. The "Three Criticisms" touch on It captures the knowledge, emotion, and will of the subjective world of human beings. The Critique of Pure Reason is the core of Kant's philosophy. The Critique of Pure Reason discusses the universal cognitive ability of human beings, which transcends the barriers of civilization and is valued in many parts of the world.

The Critique of Pure Reason, newly published by the Commercial Press, was translated by Professor Han Linhe from the Institute of Foreign Philosophy and Department of Philosophy of Peking University. Han Linhe is a well-known analytic philosopher and an expert on Wittgenstein studies. He has presided over the translation of the 8-volume "Works of Wittgenstein". He has been focusing on the study of Kant's philosophy for many years.

Regarding the choice of translation bases, Han Linhe introduced that the first edition (often called "A edition") of Critique of Pure Reason was published in 1781, and the second edition (often called "B edition") was published in 1787. Thereafter, before Kant's death, the third to fifth editions were published successively in 1790, 1794 and 1799. In 1818 and 1828, the sixth and seventh editions were published. Of these editions, only the first and second editions were modified by Kant himself, who also actively participated in the publication process. The third through seventh editions are basically reprints of the original second edition (with two additional pages of Grillo's corrections at the end of the fifth edition). According to scholars' research, Kant did not participate in the publishing process of the third to fifth editions.

Title page of the first edition of The Critique of Pure Reason (Kritik der reinen Vernunft)

Han Linhe's translation is based on the second edition ("B edition") revised by Kant himself in 1787, supplemented by the first edition in 1781 ("A edition"), which is the original edition of the Critique of Pure Reason. translate. During the revision process, the Academy edition edited by Benno Erdmann and the Philosophy Series edition edited by Raymund Schmidt were further selected as the main "collaboration editions", and other German texts and English translations were referred to. The full text has been carefully edited.It is understood that there are at least 10 English translations and at least 12 Japanese translations of Critique of Pure Reason.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a classic that is constantly translated and new, and every retranslation is a new interpretation of Kant's philosophy. There are now seven "full" translations published in the Chinese world. The first Chinese translation published in 1931, the Hu Renyuan version, was translated from the Müller version. The Lan Gongwu translation published in 1957 (translated from 1933 to 1935) was translated from Smith's translation. Mou Zongsan's version and Wei Zhuomin's version, published in 1983 and 1991 respectively, were also translated from this version. Deng Xiaomang's translation published in 2004 is based on the Schmidt edition reprinted in 1976. Li Qiuling's translation published in the same year was based on the Academy's version. The Wang Jiuxing (main) translation published in 2018 was also translated based on the Academy Edition (this translation is not a full translation in the strict sense, because it lacks the most important chapter of the book, that is, the part about the transcendental deduction of categories).

Regarding his new translation, Han Linhe introduced that he borrowed the methods of organizing and commenting on ancient Chinese books and gave a research commentary of nearly 100,000 words. These annotations include: analyzing multiple editions, examining typographical and typographical errors in historical editions; discovering and correcting Kant's own clerical errors; prompting German text editors and English translators to modify some key words, and Different understandings and possible misunderstandings caused by these factors; I carefully studied the terms referred to by pronouns in the text, and listed and compared the controversial parts; I tried to determine some popular Chinese Kant terms to explain different translators Reasons for using different translations.

Because Han Linhe has both the British empiricism and the academic background of contemporary logic and analytic philosophy, there are some places in the annotations that indicate the ideological origin of the concepts used by Kant and the inspiration for later generations. These works can help readers to grasp the Critique of Pure Reason more deeply, and also provide a contemporary philosophical perspective for German classical philosophy.

During the seminar, Wang Bo, vice president of Peking University, pointed out that the Critique of Pure Reason translated by Han Linhe is the eighth Chinese translation. The Chinese world needs to overcome the barriers of language and time to understand Western culture. The sense of language is connected with our breath. Li Qiuling, an expert in Kant research and the translator of the Chinese version of the Complete Works of Kant, said that translating academic works is not simply a matter of language conversion, but requires in-depth research and the accumulation of predecessors. Han Linhe's new translation balances many conventional terms in the academic world, and also gives detailed annotations, indicating the source of some key words in different versions and translations, giving readers a lot of convenience. Xie Dikun, an expert on Kant studies, pointed out that translating Kant's classical philosophy from the perspective of analytical philosophy has unique methodologies. The footnotes in the book are also impressive.

During the seminar, Wang Bo, vice president of Peking University, pointed out that the Critique of Pure Reason translated by Han Linhe is the eighth Chinese translation. The Chinese world needs to overcome the barriers of language and time to understand Western culture. The sense of language is connected with our breath. Li Qiuling, an expert in Kant research and the translator of the Chinese version of the Complete Works of Kant, said that translating academic works is not simply a matter of language conversion, but requires in-depth research and the accumulation of predecessors. Han Linhe's new translation balances many conventional terms in the academic world, and also gives detailed annotations, indicating the source of some key words in different versions and translations, giving readers a lot of convenience. Xie Dikun, an expert on Kant studies, pointed out that translating Kant's classical philosophy from the perspective of analytical philosophy has unique methodologies. The footnotes in the book are also impressive.It is reported that the Critique of Pure Reason, as Kant's "first critique", starts from the understanding of why it is possible, criticizes and sublates rationalism and empiricism, and believes that there are two sources of human knowledge: one is provided by human senses Acquired perception experience; one is the innate form and category in human thinking that brings inevitability and universality to knowledge, and is an "innate comprehensive judgment" applicable to the phenomenal world. The main discussion in the book revolves around "innate comprehensive judgment".

"Innate comprehensive judgment" is not difficult to understand. It refers to a kind of judgment that is universal, inevitable, and can provide real knowledge. The difficulty lies in "how is the innate comprehensive judgment possible". This question concerns the process of how innate knowledge forms and empirical knowledge matter constitute knowledge. Kant's transcendental self provides the a priori form of knowledge, thus ensuring the universal inevitability of knowledge; his thing-in-itself provides the material of experience, enabling us to continuously acquire new knowledge content. Kant decomposes the core question of "how is a priori synthetic judgment possible" into four questions, namely, how is pure mathematics possible? How is pure natural science possible? How is metaphysics as a natural inclination possible? How is metaphysics as a science possible?

In his discussion of these issues, Kant pointed out that the subjective (transcendental self) provides the form of knowledge, and the objective (the thing-in-itself) provides the material of knowledge, and the combination of the two constitutes empirical knowledge or knowledge with both universal inevitability and new content. Scientific knowledge, which is the basic principle behind the possibility of a priori comprehensive judgment. Kant's entire epistemology is mainly divided into three steps: sensibility, intellect, and reason to illustrate how the two are combined.

More subversive in the perceptual stage is Kant's view of time and space. The transcendental self provides an innate form of intuition for our cognition, which is time and space, and it is through these two forms of intuition that we form our perceptual cognition of phenomena. Kant believes that time and space are not the existence forms of objective things themselves, but a form of subjective cognition of the objects we feel. Kant believes that space is the form of external senses, that is, the innate form of intuition about all external phenomena; time is the form of inner senses, that is, the innate form of intuition of all internal phenomena (inner state).

The intellectual stage also has some innate forms of knowledge, that is, "innate thinking forms", which are expressed in twelve categories, namely singularity, plurality, and totality; reality, negation, and limitation; substance and accident, Cause and effect, active and passive; possibility and impossibility, existence and non-existence, inevitability and contingency. The cognitive activity in the intellectual stage is to use these categories to synthesize and unify the phenomena that are already in space and time. By adding these twelve categories to different phenomena, empirical knowledge or scientific knowledge with universal and inevitable connection is formed.

In the perceptual stage, we endow the perceptual material with the innate intuitive forms (space and time), form phenomena, and produce mathematical knowledge; in the intellectual stage, we use the innate thinking forms (categories) to synthesize the phenomena that have been formed in the perceptual stage unification, resulting in natural scientific knowledge. Entering a higher level of "rationality" requires a transition from the specific knowledge of the intellect to the more complete absolute knowledge. For example, go further from specific psychological knowledge to knowledge about the "soul" itself, and from specific physics knowledge to knowledge about the "universe" as a whole.

Related Posts