Zhang Mu, a Guangdong painter in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, was born in Chashan, Dongguan. ). In his life, poetry and paintings are more important than the times, so there are many important accounts of his life, friendship, festival meaning, poetry, and paintings. Since the 20th century, Rong Geng has written "Zhang Mu Biography", Wang Zongyan and Huang Sally edited "Zhang Mu Chronicle", Shan Xiaoying edited "Lingnan Painting Library Zhang Mu Scroll", and Xu Dunping wrote "Images of the Collective Memory of the Remnants of the Ming Dynasty". Reappearance - An Analysis of Zhang Mu's "Seventy Dragons Media Map", etc. With pearls ahead, breakthrough research is not easy to do. Zhang Mu is well-known for his horse painting. Many commentators talk about Zhang Mu's artistic achievements in terms of horses, eagles, orchid bamboos, and figures, and discuss the remnant complex and political metaphor implied by his dismounting of horses and eagles. Cow is rarely mentioned because of the rarity of paintings.

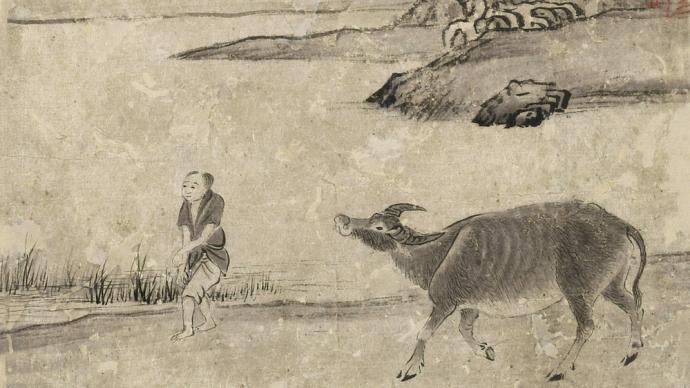

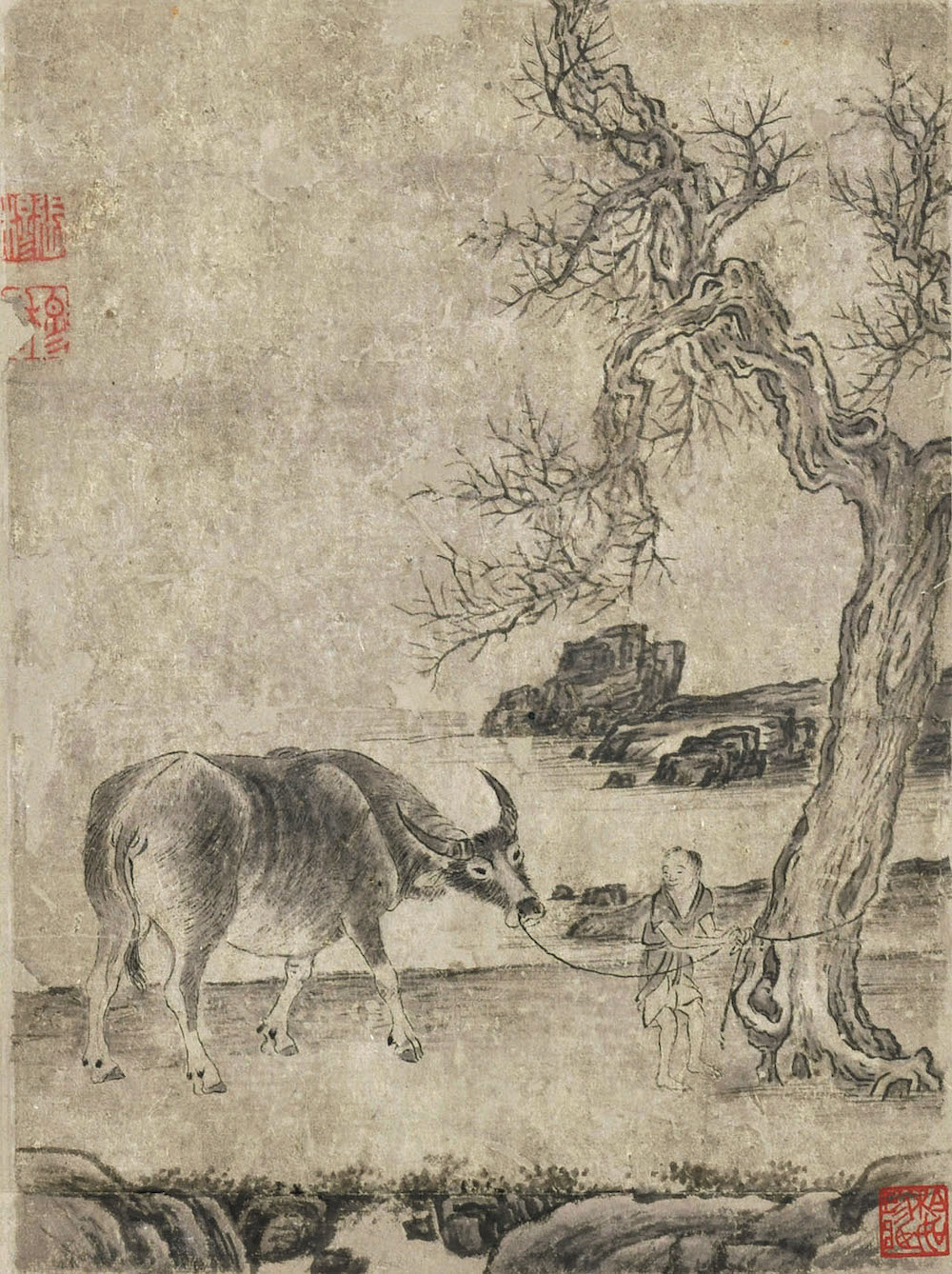

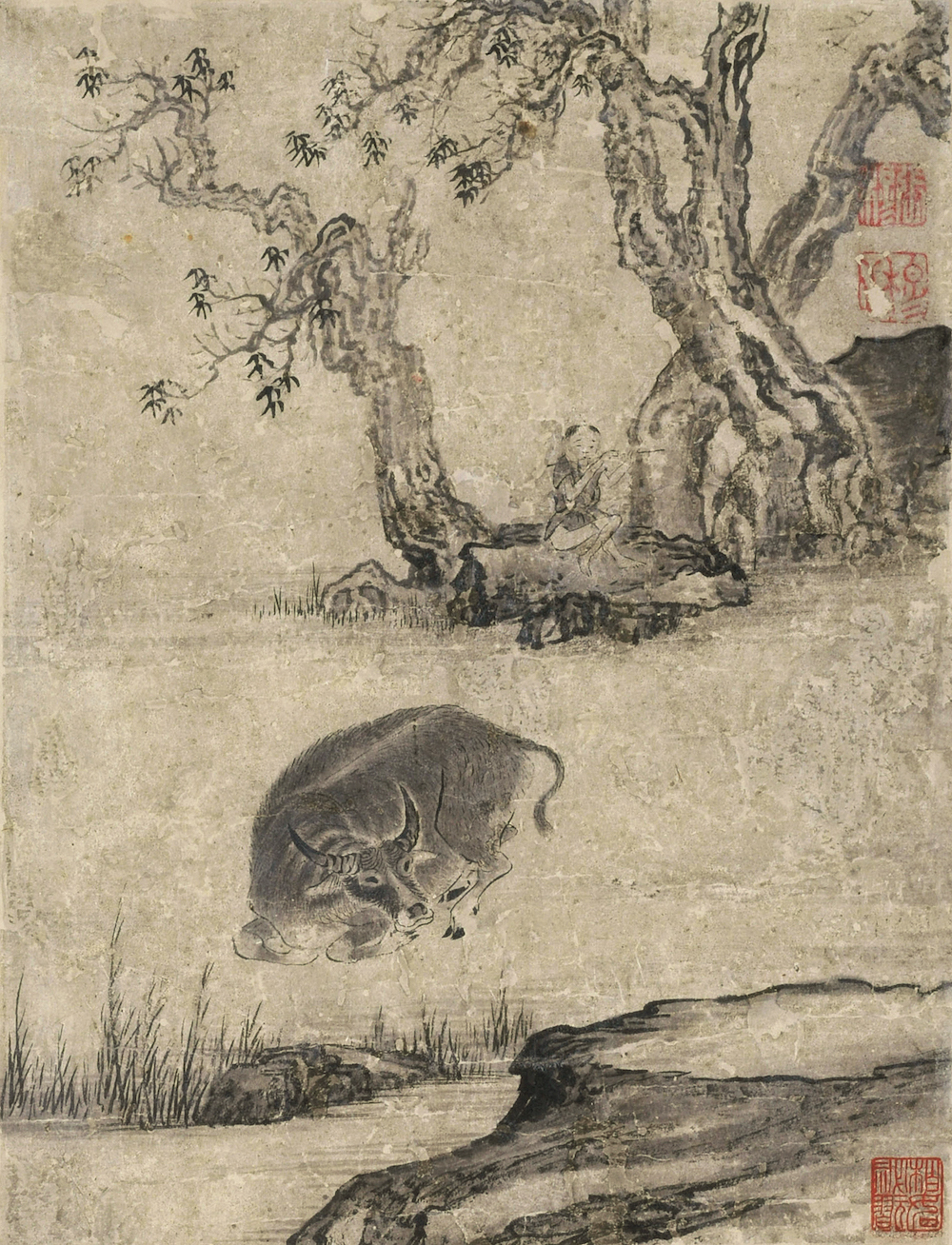

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Mu Niu Atlas·Preliminary Coloring on Paper

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Mu Niu Atlas · Preliminary paper coloring 23.7 cm vertical 17.7 cm horizontal Mr. Yang Quan donated the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

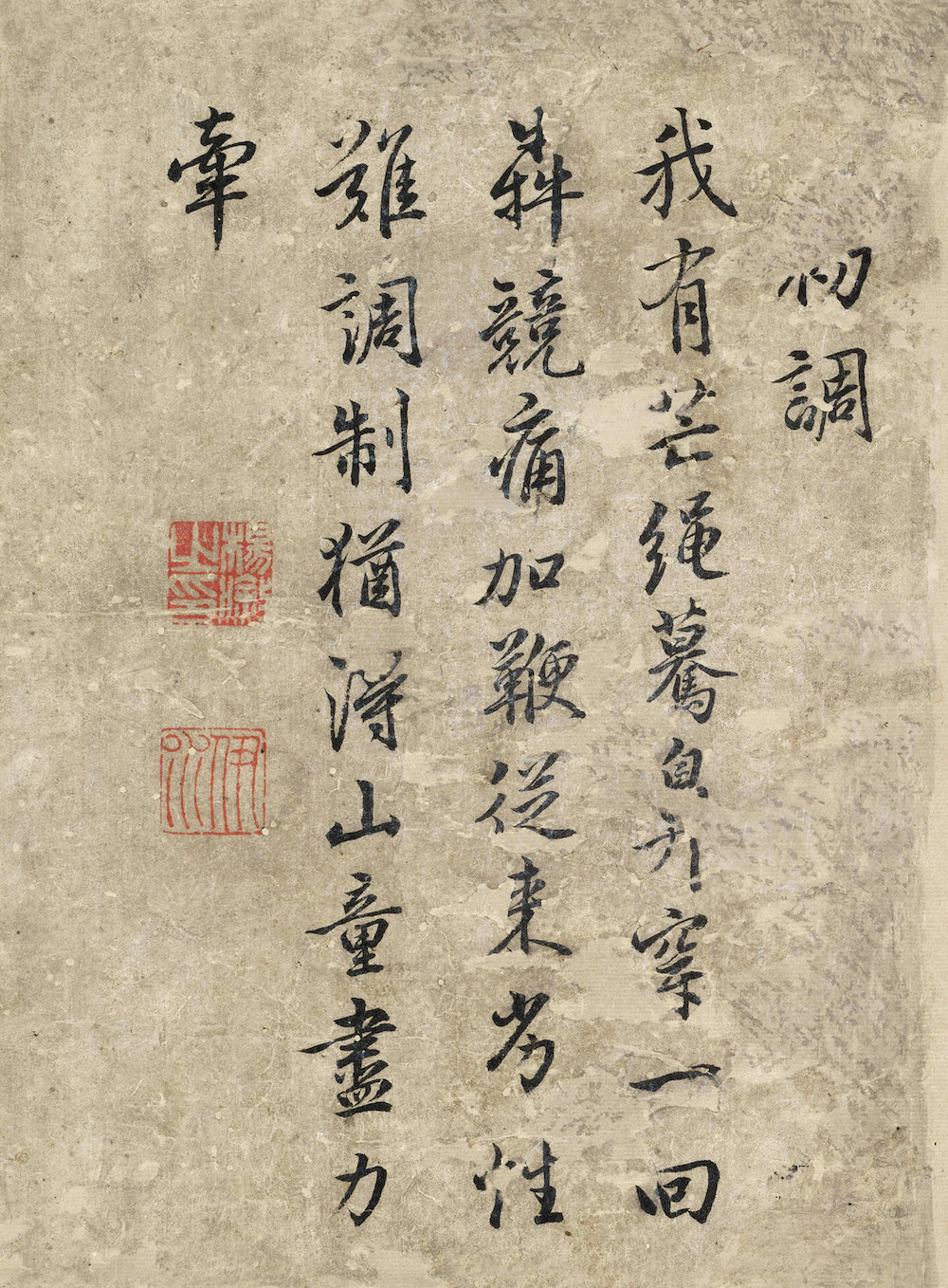

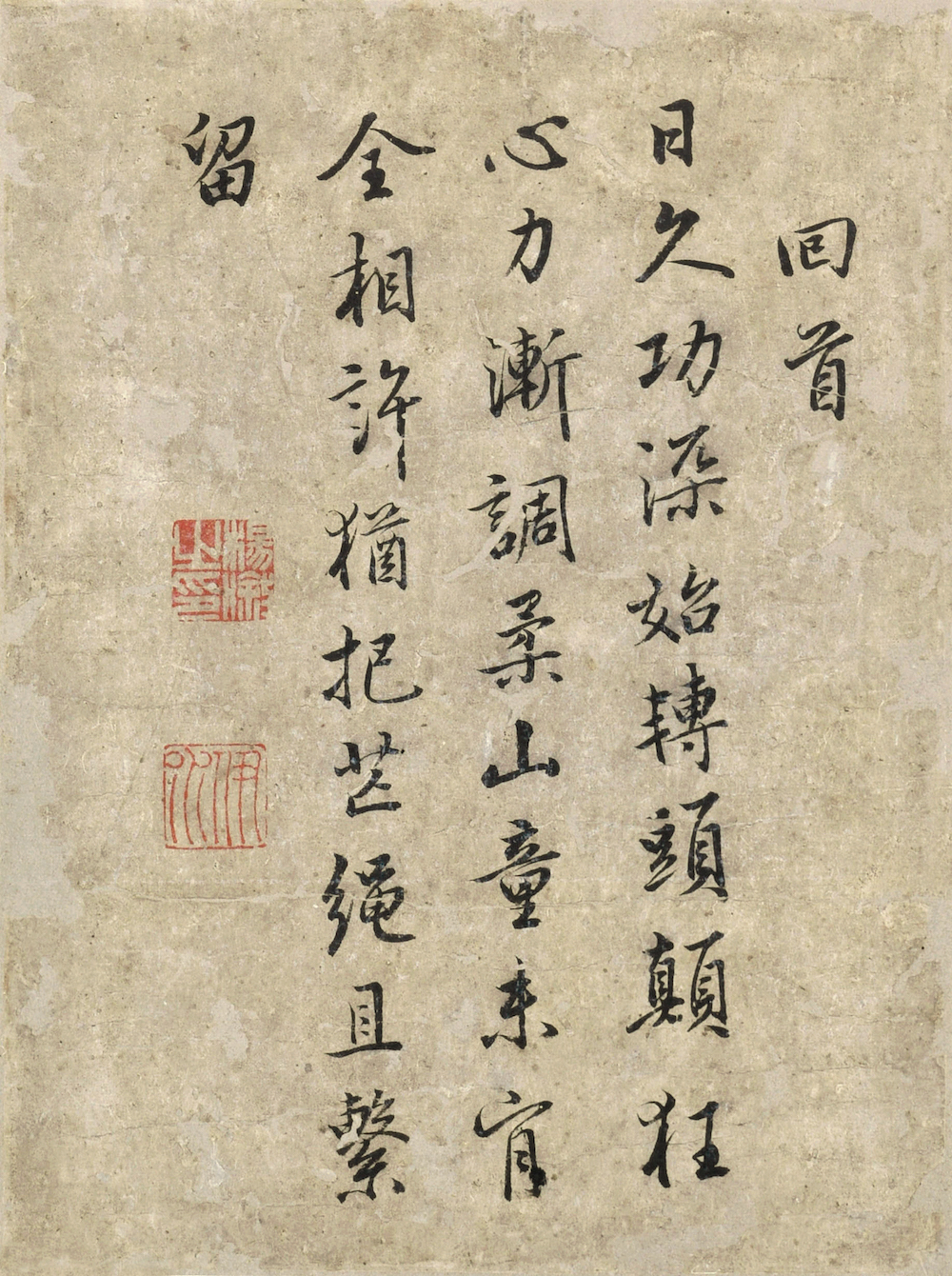

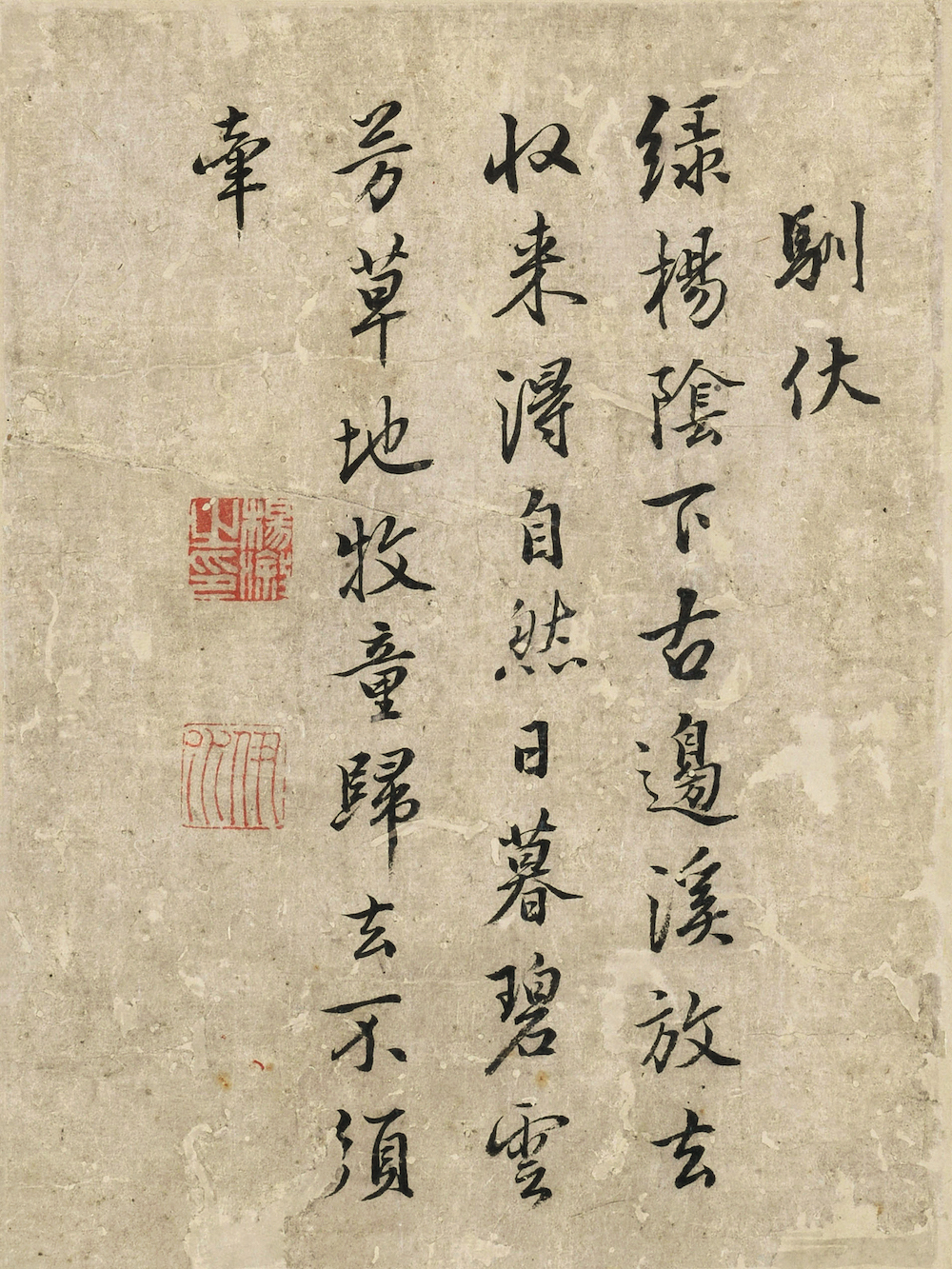

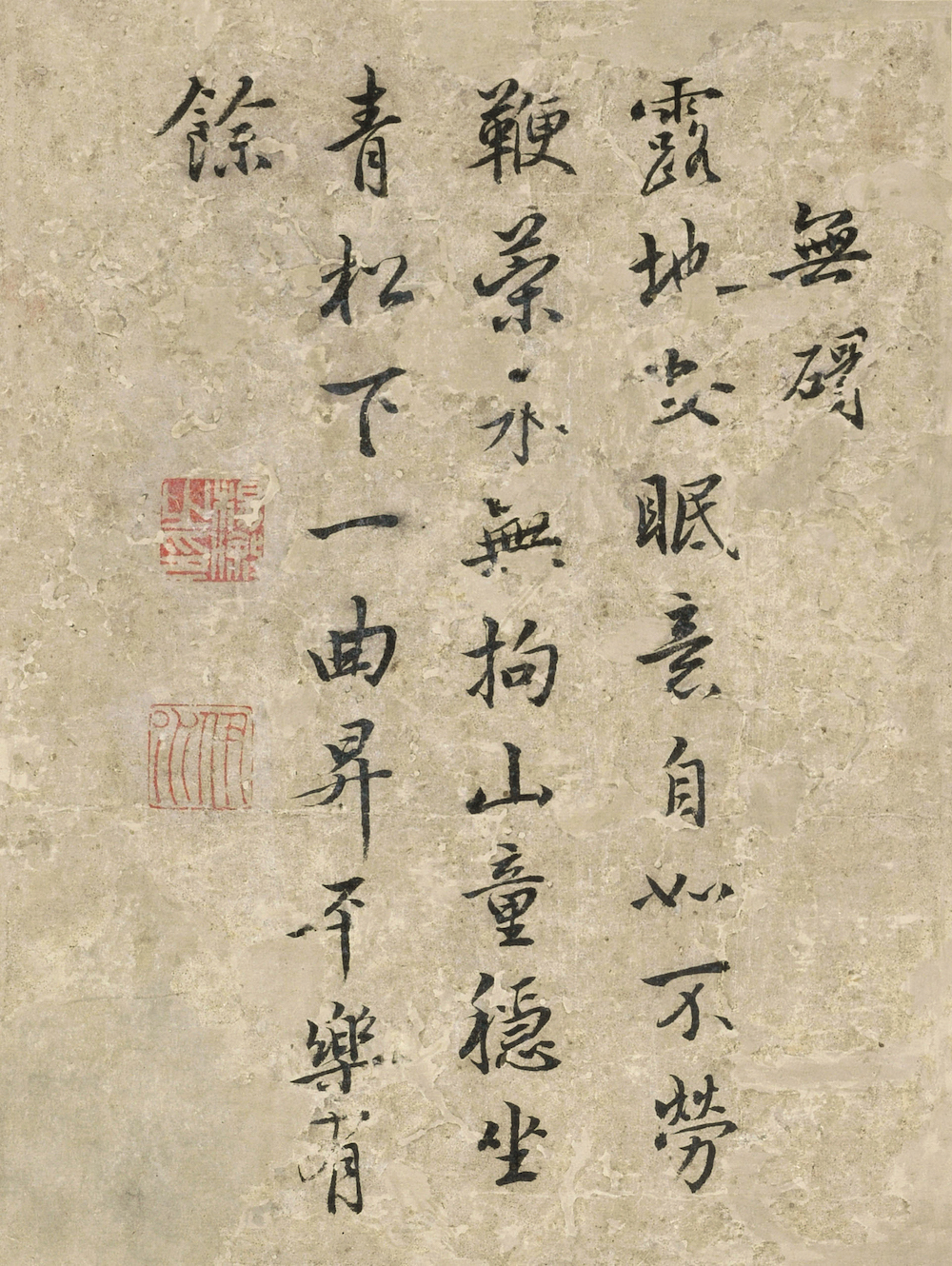

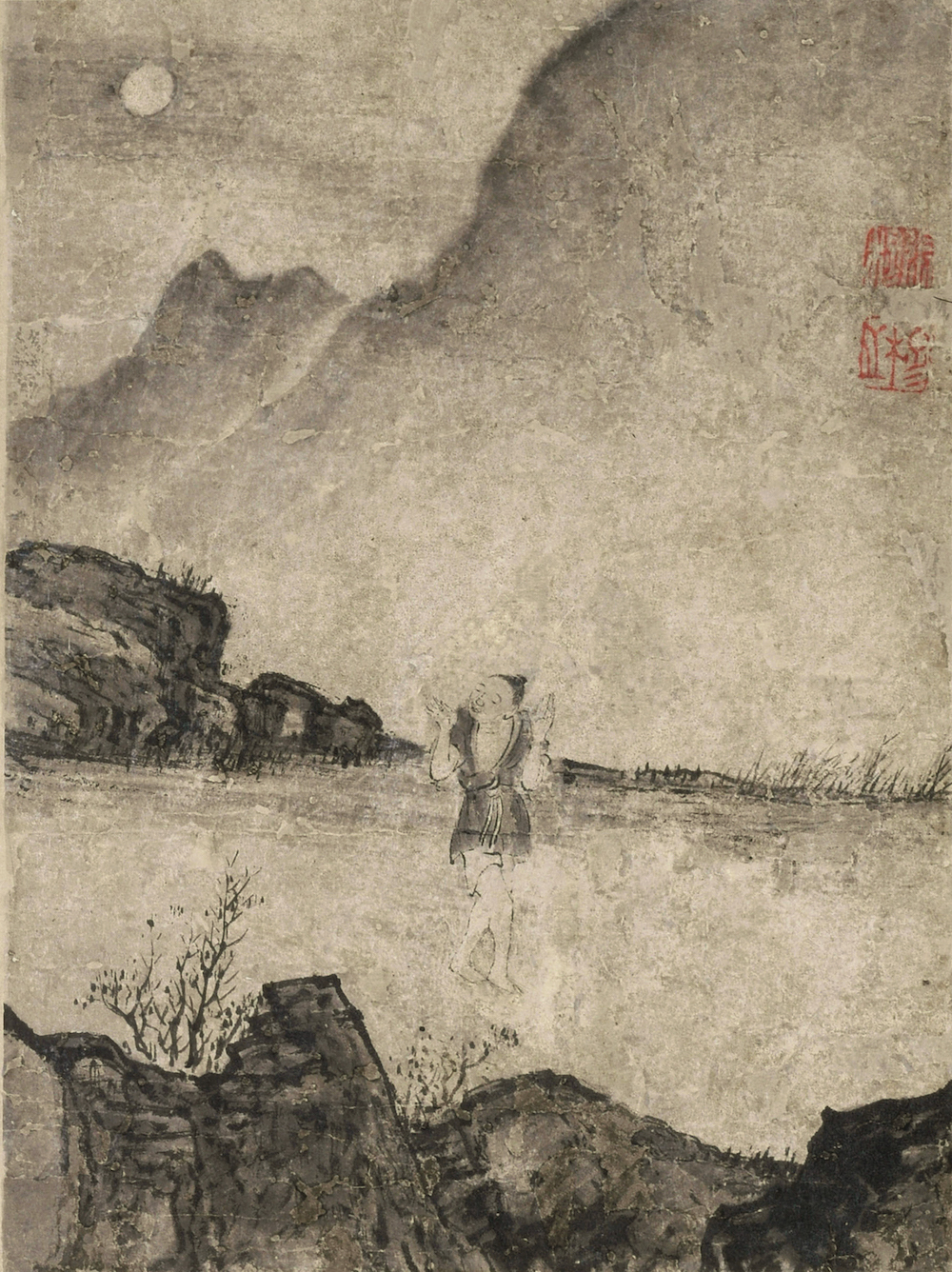

At the time of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, Lingnan became a famous source for the remnants to escape from Zen, and its Buddhism stood on the three pillars of southern Yunnan and Jiangnan. They either took ordained ordained and directly supported themselves in temples, or converted to become laymen, and became an important group of scholars and monks in Lingnan in the early Qing Dynasty. In his later years, Zhang Mu, a hero who had no way to serve the country, began to turn to Buddhism to find a good way to rest his body and mind. According to research by Wang Zongyan and Huang Sally, Zhang Mu converted to Taoist monk at the age of fifty-two (AD 1658). He had a lot of contacts with the Taoist monk Fa Shi Tianran and his disciples of the current generation and refugees, such as Jinshi and Chen Zizhuang. Some commentators believe that Zhang Mu converted to Taoism in his later years, but at present there are not many materials about Zhang Mu's belief in Buddhism and Taoism. This set of "Cattle Cattle Atlas" may provide a glimpse of Zhang Mu's thinking on Buddhism, and provide some clues for understanding the spread of Lingnan Zen Buddhism in the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties.It is an eight-volume set of "Cattle Cattle Album", which is now in the collection of the Guangzhou Art Museum, each with an inscription by Yang Xu (active in the 17th century). There is no record of handing over the album from the early Qing Dynasty to the Republic of China. It can be seen from its seal that this album was collected by Guangdong collectors and Dongguan Liang Boru during the Republic of China. After it was handed over to Yang Quan, Yang Quan donated it to the public collection. Although this album is small in size, it has fine brushwork. The brush strokes and ink habits of trees, stones, cows, smudges, and rubbing, as well as inscriptions and seals, all correspond one-to-one with the handed down original works of Zhang Mu. The author of the question, Yang Xu, whose life is not available, should be contemporary with Zhang Mu. In a set of "Eighteen Arhats", which was passed down to the Yuan Dynasty and was anonymous, the authors of each opening are Xie Changwen, Jinshi, Chen Gongyin, Yang Zhongyue, Tang Yuanji, Wu Qiu, Shi Jian, Yang Xu, Wei Qu, Nong Shanyu, Cheng. Shi Shi, Ruan Jie, Fang Guohua, Jin Wu, Zhang Mu. This set of paintings was collected by Pan Xi and Liu Zuochuo in the middle of the 20th century. It was exhibited at the Guangdong Cultural Relics Exhibition in 1940 and is now in the collection of the Hong Kong Museum of Art. The opposite of Zhang Mu's "Atlas of Cattle Shepherd" and the anonymous "Book of Eighteen Arhats" proves that Yang Xu and Zhang Mu were contemporaries, and both of them were in the circle of Ming survivors and should have had contacts. The inscription "Written on the Dragon Boat Festival of 1911, by Zhang Mu" in the "Cattle Cattle Album" shows that the album was made in 1671 (the tenth year of Kangxi's reign), and was a work of Zhang Mu in his later years (then he was sixty-five years old). This album was included in "Selected Paintings and Calligraphy of the Past Dynasties in Dongguan" and "Lingnan Painting Library·Zhang Mu". Zhang Mu's "Cattle Cattle Album" is based on the "Ode to Cattle Cattle" (also known as "Ode to Ten Ox", collectively referred to as "Ode to Cattle Cattle") by Zen Master Puming. The title and poems written by Yang Xu are also all recorded in the verses of Chan Master Puming's "Ode to Shepherd Cattle". Therefore, it can be concluded that the "Cow Shepherd Atlas" should have been a ten-open volume, and its titles were "Wei Mu", "Primary Tuning", "Restricted", "Looking Back", "Tame and Subdued", "No Obstruction", "Ren Yun" and "Forgetting" "Single Photo" and "Double Desolation". It is a pity that in the process of circulation, two openings were lost, namely the first opening "Wei Mu" and the third opening "Restricted".

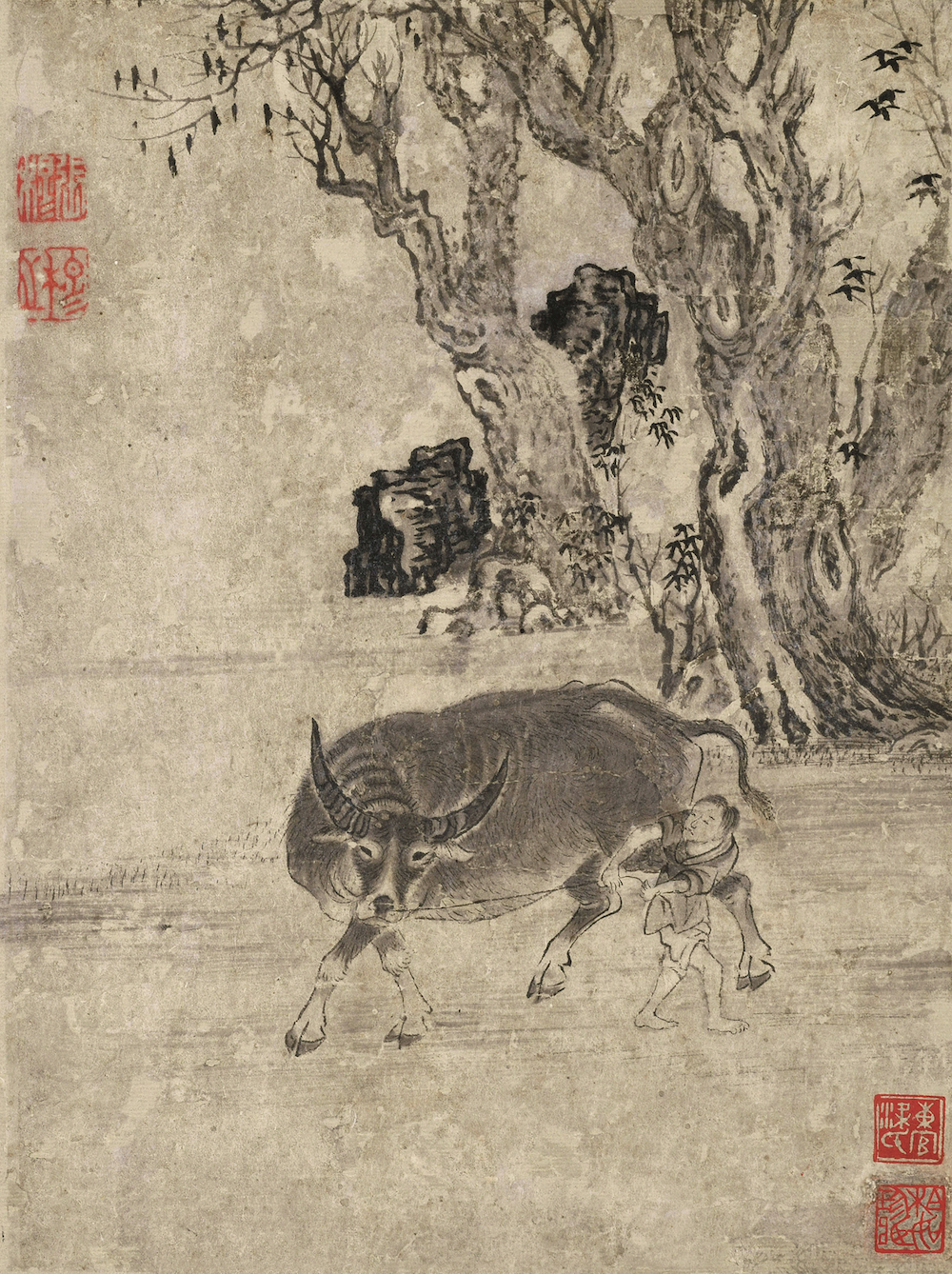

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Looking back on paper and coloring, 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Looking back on paper and coloring, 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the Guangzhou Art Museum

Taking the cow as an analogy is a well-established and convenient method of representation in Zen Buddhism. "Cow" is a metaphor for the human nature, and the different states of "grazing cattle" are a metaphor for the different processes of cultivating the mind and proving the Way. From the ten stages of "weimu" to "double desolation", it is metaphorical that Buddhist practitioners go from ignorant of the Buddhist Dharma to the different stages of cultivation of human hearts. Buddhism believes that people indulge in all kinds of desires because of ignorance, struggling to get rid of it. In order not to be affected by external desires and fall into the sea of misery, one needs to control the nature of the mind, just like a cow. Therefore, "ox" is a metaphor for the human heart, and "cow herding" and "bringing cows" symbolize different stages of mind control. White cow". Regarding the classics that use the cow as a metaphor for convenient representation, it can be traced back to the early three Tibetans, such as the "Ahan Sutra", "Zha Ahan Sutra" and "Buddha-like Mudhuan Sutra". Beginning in the mid-Tang Dynasty, there are also many stories in Zen texts about the metaphor of cow herding, such as "Shi Gong Monk", "Fuzhou Xiyuan Monk" and "Wuguan Mountain Ruiyun Temple Monk" included in "Ancestral Hall Collection". . For example, in the widely circulated "Shi Gong Monk", its story is:After the teacher was doing chores in the kitchen one day, Ma Shi (Ma Zu Daoyi Zen Master, (AD 710-788)) asked: "What do you do?"

To Yun: "Cow herding."

Master Ma said, "What do you do as a shepherd?"

He replied, "As soon as I get into the grass, I pull my nostrils in."

Ma Shiyun: "Zizhen herds cattle."

Mr. Cai Rongting's research pointed out that this kind of koan Zen language, which uses cow herding as a metaphor for the process of cultivating the mind and proving Taoism, has the forms of poetry, verses, singing praises, sayings of common sayings, distinguishing pairs of machines, and asking questions about Zen meditation. It was very popular at the time of the rise of Zen Buddhism. At the same time, by combing through the literature, Mr. Cai also found that the opportunistic French related to cattle herding in the Tang and Five Dynasties all came from Caoxi Huineng's legal system.

(Ming) Zhang Mu's cattle-grassing album · taming on paper, coloring 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's cattle-grassing album · taming on paper, coloring 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

Based on the existing Buddhist prints and Chinese paintings, the painting themes with cattle-herding as a metaphor came into being relatively late, while the stylized and popularized prints of "Cow-herding" or "Ten Niu" may be even later. Chan Master Puming's "Ode to Cattle Herding" is the most popular version of the cow herding picture in the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the Ming Dynasty, Chan Master Yun Qihong (1535-1615 AD) wrote the preface to Puming's "Ode to Herding Ox" (Wanli Jiyou, AD 1609) as follows:The "Last Teaching Sutra" says... There is a picture after the painting, starting from Weimu, and finally double-dead, and it is listed as ten; . And Puming is a series of eulogies; Puming has not specified who the people are, and I don’t know if the picture song is the hand of one person? No matter today.

From this, it can be seen that people in the Ming Dynasty have no way to study why Puming was a person, and who did the picture song come from. But what is certain is that during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty, the "Ode to Cattle Shepherd" by Zen Master Puming became quite popular. This version was reprinted several times during the Qing Dynasty. It is believed that this is related to the prosperity of the engraving industry during the Wanli period of the Ming Dynasty. This popular Puming "Ode to Cattle Cattle", which was popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties, is the representative of the Ming Dynasty martial arts prints. At the same time, under the corrupt and absurd government of the late Ming Dynasty, scholars believed in Buddhism, obtained spiritual insight and savvy from Buddhism, and realized the ideal of "retirement".

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Ink and color on paper, 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Ink and color on paper, 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

Another popular version of "Ode to Shepherd" is "Ode to Ten Ox" by Zen Master Kuo'an in Song Dynasty. This picture ode is also composed of ten pictures, each picture contains a verse, and the ten stages are: searching for the cow, seeing the trail, seeing the cow, getting the cow, herding the cow, riding the cow and returning home, forgetting the cow, missing the man and the cow, returning to the origin and returning to the source, and entering Jiang lowered his hands. In the eighth stage, "people and cattle disappear", which is equivalent to the Puming version of "double annihilation", and the subsequent "return to the original source" and "return to the house" and "hanging hands", preaching that after the personal enlightenment is complete, it is still necessary to enter the world again. , translate what you have gained into others, and guide others to share liberation. Kuoan's version is more in line with the ultimate concern of Mahayana Buddhism than Puming's version. Today, the Kuo'an version is more favored by the Rinzai sect of Zen, while the Puming version is more favored by the Caodong sect of Zen.

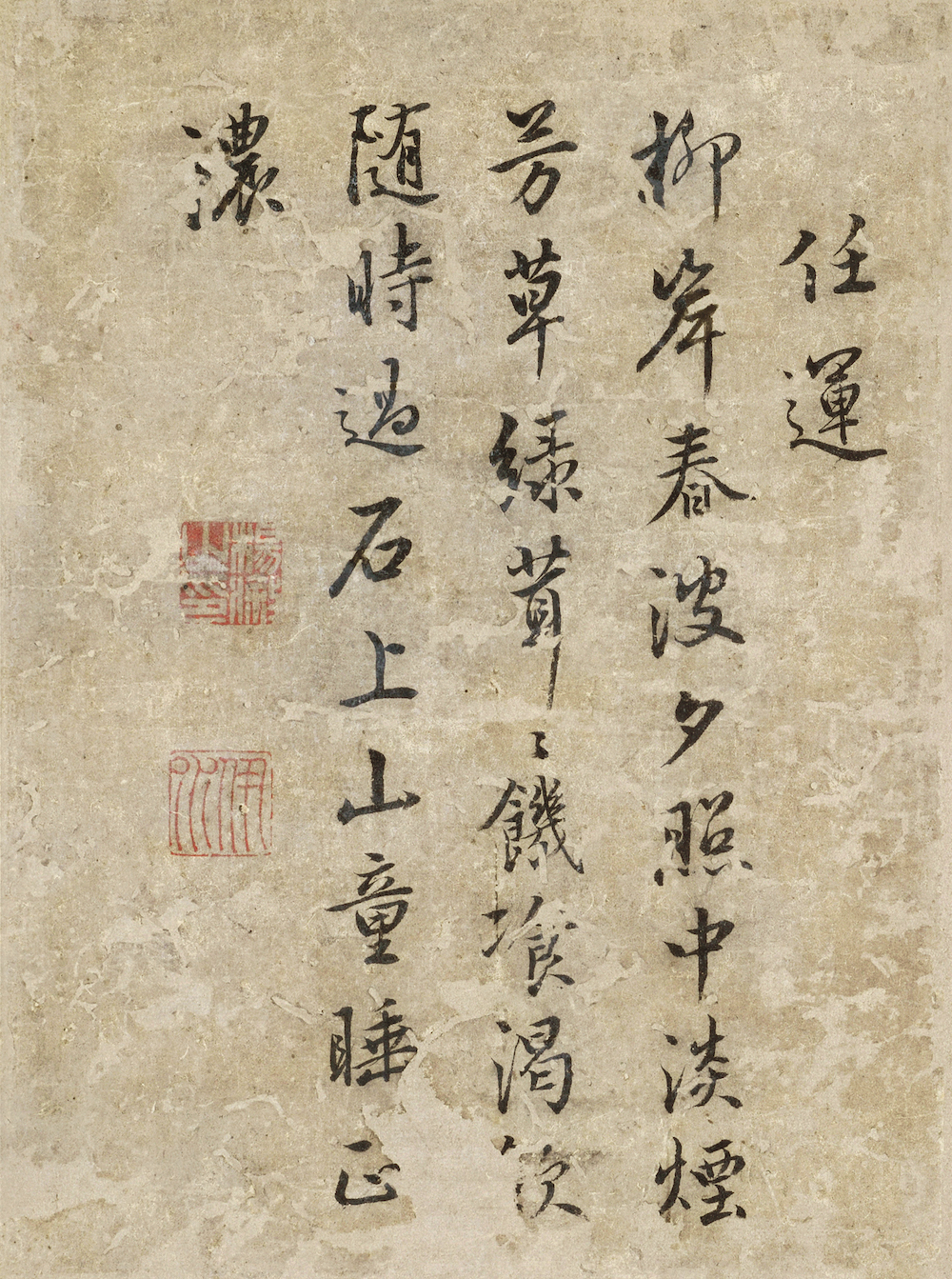

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas·Ren Yun Paper and color, 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas·Ren Yun Paper and color, 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

However, from the mid-Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty (at least before the Kangxi period), the Kuo'an version was not popular. Chan Master Hong mentioned in the preface of Puming's "Ode to Shepherd Cattle": "Outside, there are more cattle hunting and even entering the shop. It is also the tenth picture. It is similar to today. It is also the order of training in the teaching. It can be known in proportion. Attached at the end of the brief for reference." Master Hong thought that the formulation of "similar to today's" is debatable. But this passage proves that Kuo'an's version was also seen in the Ming Dynasty, but it was not popular. For the convenience of the followers, the editor also appends its pictures to the back, but only the pictures and no verses. During the Kangxi period, when Master Jialing Xingyin republished the "Ode to Shepherd Cattle", he said in the "postscript": "Liangshan Yuanyuan sang, my teacher Meng, the old man, has not seen it for forty years. The monk's office is overjoyed. But the original number of the postal stamps is empty." It can be seen that the "Ode to Ten Bulls" by Zen Master Kuo'an was still not popular in the early Qing Dynasty. Only the picture and the song are compatible. The earliest illustrated and textual Zen Master Kuo'an's "Ode to Ten Bulls" can be found in the Wushan edition in the old collection of Saburo Matsumoto (1869-1944), Institute of Humanities, Kyoto University, Japan. According to the research of the Japanese scholar Yanagida Shengshan, from the Kamakura period (AD 1185-1333) to the Muromachi period (AD 1338-1573) Japan was influenced by Zen Buddhism in the Song Dynasty, and Kuan Shiyuan's "Ode to Ten Bulls" was introduced. It was not until the beginning of the Edo period (AD 1603-1867), due to the introduction of macro reprints, the "Ode to the Ten Bulls" in the Puming version was not known. Contrary to the situation in Japan, the Puming version was popular in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties, and it was not until the early Qing Dynasty that the Kuoan version gained renewed attention.In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Zhang Mu's "Cattle Cattle Album" should be based on the popular Zen Master Puming's "Ode to Cattle Cattle", and it has some creative play. Each frame of Zhang Mu's "Cow Herding Album" shows the plot of the interaction between people and cattle, which is consistent with the engraved version. But comparing the two "cattle pictures", first of all, it is not difficult to find that Zhang Mu's "cattle album" obviously lacks the gradual process of Zen Buddhism's "cow" (human heart) from black to white, only in the eighth picture "phase" In "Forget", an all-white ox is drawn, and the verse to solve the problem is hidden: "The white ox is always in the white cloud". Secondly, Zhang Mu's landscape backgrounds, such as trees, rocks, and the dress of the shepherd boy's shorts and shorts, all have the feeling of Lingnan countryside. Ms. Li Huanzhen also believed that Zhang Mu was depicting cattle herding in the Lingnan countryside. It can be seen that, while referring to the classics, the painter integrates his own understanding of Buddhism as well as his personal artistic creation experience and life experience.

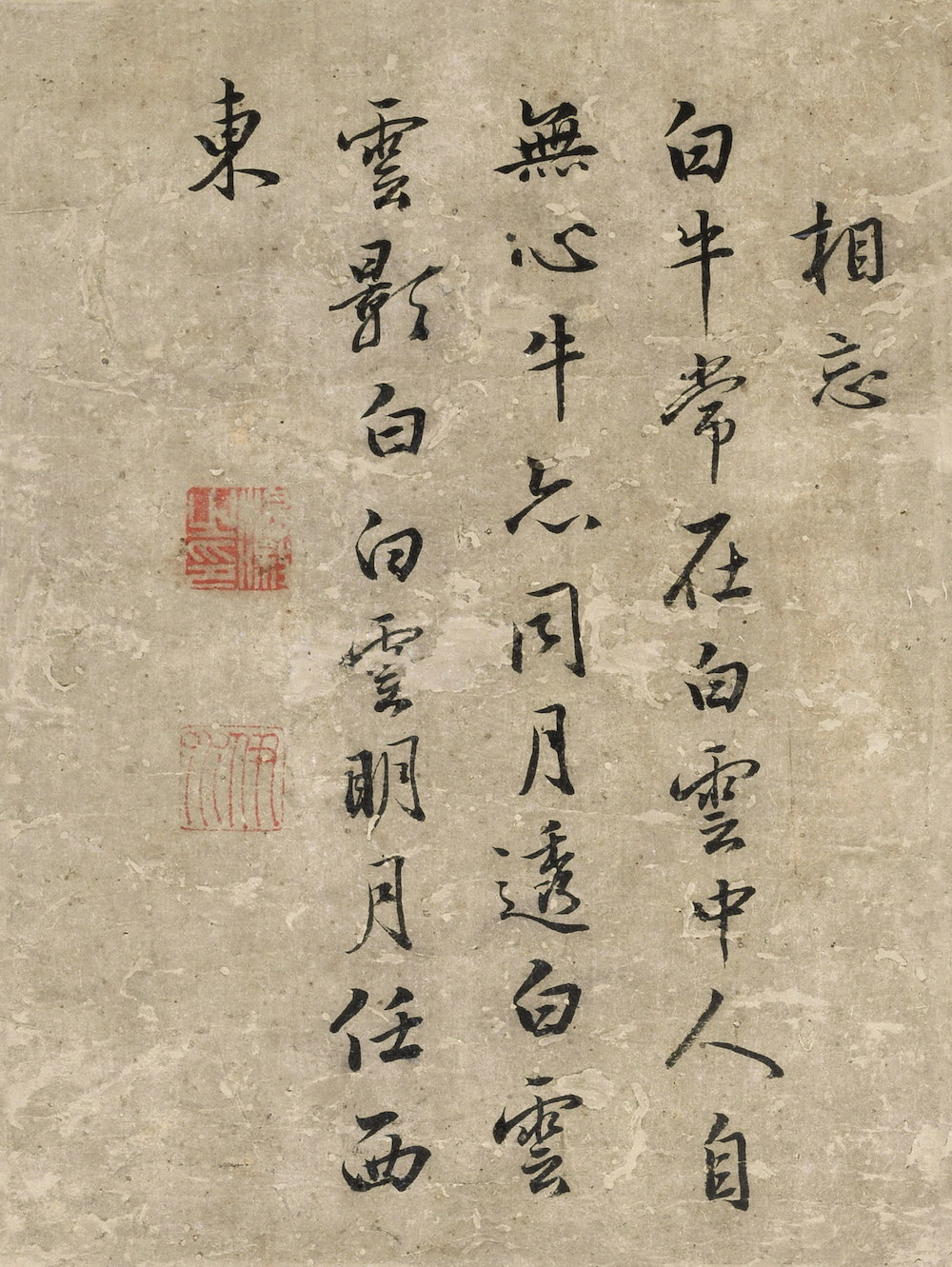

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas, Xiang Wang, ink and color on paper, 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas, Xiang Wang, ink and color on paper, 23.7 cm in length and 17.7 cm in width, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

The painters who painted cattle herding in the Ming Dynasty were not only found in Zhang Mu. Zhang Hong (1577-1652 AD) also painted a set of "Cattle Cattle Atlas". This atlas is in twelve folios, two of which are inscriptions and postscripts, including the preface to Puming's "Ode to Shepherd Cattle" written by Zen Master Yun Qihong and the process of this painting being circulated. The remaining ten are from ungrassed to double-dead. Each frame of pictures is accompanied by a page of inscriptions, which not only record Puming's poems, but also sing in harmony. Based on the engraved version of the "Ode to Cattle" in the Qing Dynasty, this practice of singing and verse was quite popular at that time. Zhang Hong's activity location is also in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, where the engraving industry is extremely developed. It is estimated that his paintings are also deeply influenced by his time books. Zhang Hong's inscription also mentioned that the friend who asked him to paint this album was "good Taoism". Of course, the paintings are not exactly modeled after the prints. Zhang Hong is an excellent painter, so his "Cow Cattle Atlas" has a fresh and elegant style, and his brush, ink and composition are all unique.Whether it is Zhang Hong's "Atlas of Cattle Shepherding" or the Qing Dynasty engraved version seen today, there are details of the gradually turning white of the cow. Master Hong clearly mentioned in his preface: "It begins with no shepherds, and ends with stagnation. It is ranked as ten in terms of quality. The cattle are as follows: first black, then white, until they are not as charming as they are." In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, the Lingnan Zen Forest was closely related, and the "bull" in his pen lacked the explanation of the transition from all black to all white, which is obviously intentional rather than a temporary negligence. In Zen's understanding of Buddhism, there are two propositions: gradual enlightenment and sudden enlightenment. Zhang Mu's "bull" is a metaphor for epiphany. It is undeniable that this set of "Cattle Cattle Atlas" is very likely to be a social entertainment work entrusted by others, but the subtleties can also reflect Zhang Mu's state of mind.

Zhang Mu was a suave man, but he was not good at Confucianism, and he had the ambition to make contributions to the country since childhood. He was born in the late Ming Dynasty. His father was a teacher of Guangning and the magistrate of Bobai County. His family was not bad. When he was young, he studied in Luofu Stone Cave. He has traveled to the north of the Lingbei, thinking of making contributions to the frontier fortress. Attached to the Tang King of Nanming, he and Zhang Jiayu recruited troops to fight against the Qing Dynasty. When Nanming entered Guangdong and started civil strife with the same room, he resigned in disappointment and returned to Dongguan to return to seclusion, and never returned. Within a few years, his friends Zhang Jiayu, Chen Zizhuang, and Chen Bangyan were killed in battle, and Guangzhou was also captured by Qing troops. He likes to draw horses and eagles, which is most likely related to his martial character.

In his later years, Zhang Mu entertained himself with poetry and painting, and liked to practice Buddhism. He is not only a lay disciple of the Taoist monk, but also has close contacts with the disciples of the current generation of "Haiyun Shijin", who is the natural monk of the Taoist monk, and he often sings poetry and prose. In the fifteenth year of Shunzhi (AD 1658), his poem " Going to Dangui Monk Youtang", there is a self-note: "Yu's family in the East Lake, go to the mustard temple in a water room, or let the boat often go to the old monk Kongyin, and meet Dangui. When the master talks at night, Xu Yu’s poems express his temperament, and he prefaces them with sympathy.” At that time (AD 1653-1665, from the tenth year of Shunzhi to the fourth year of Kangxi), Zhang Mu had retired to Dongguan and built Dongxi Thatched Cottage to live in the east of the city. The Thatched Cottage is separated by water from the Huangcun Jie'an where the monks Daodu (Kongyin) and Jinshi (Dangui) lived, so Zhang Mu often went to Jie'an by boat to chat with them elegantly. Dongguan Ji'an is an important place for Taoist monks to spread the Dharma. Monk Daodu (1600-1661 AD), a native of Nanhai, Guangdong, heir to the 33rd generation of Caodong Sect Mustard Um. After Dao Du passed away, his legal heir became a natural monk. In order to express the inheritance of the temple abbot of this teacher, Huashoutai, Ji'an, Haizhuang Temple, etc. were also symbolically abbot in turn.

Zhang Mu had close contacts with the Lingnan survivors and monks, and even converted to Buddhism. From this, it can be affirmed that Zhang Mu was quite familiar with the meaning of "cow herding" in Zen Buddhism. At the same time, from the Wanli period of Ming Dynasty to Kangxi period, Zen Master Puming's "Ode to Shepherd Cattle" has been reprinted and widely distributed. In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, scholars and monks from the Jiangnan area came south to fight against the Qing Dynasty and avoid disasters. It is more possible to flow into Lingnan. This set of "Cattle Cattle Atlas" is not the only "Cattle Cattle Picture" drawn by Zhang Mu that is related to Buddhism. Monk Dangui's anthology also includes an inscription he wrote for Zhang Mu's "Cow Herding Picture". He wrote:

Lianzhai entrusted this picture with the words "once you enter the grass, you will drag your nose in the future". The iron bridge seemed to throw the ropes aside. Goode also eulogized: "Two horns point to the sky, four feet on the ground, pulling the nose rope, shepherds shit." Knowing the meaning of this eulogy, I began to understand the meaning of abruptly and pulling back.

In this inscription, Monk Dangui specifically pointed out that although Zhang Mu was asked to draw cattle herding pictures, his cattle were not restrained by ropes. Dangui explained that if the nose rope is pulled off by looking at the cow, then it is even more impossible to herd the cow. Wang Ling served as an official in Guangdong between 1670 and 1681, and had contacts with Zhang Muduo in his later years. He also mentioned: "I have seen "The Picture of Cattle Shepherd" presented to Da Shi (Shi Jinwu), and Yan Lan will be born with the ridge and mu. If the nostrils are lifted up, the cattle rope will be lost, and I will not ask the shepherd again." It can be seen from the text that Zhang Mu also painted a picture of a cow that is still not restrained by a cow rope for his friend Jinwu Monk. There are not many works of Zhang Mu's paintings of cattle, but the "Cattle Cattle Atlas" and the cattle-grazing pictures recorded by monk Dangui and Wang Ling are enough to prove that Zhang Mu not only painted cattle-grazing pictures several times, but also has a good understanding of the meaning of "cattle-grazing" in the Zen classics. quite familiar. He did not paint exactly according to the content of the verse, showing that he had a personal view on the "grazing of cows" in Zen Buddhism.

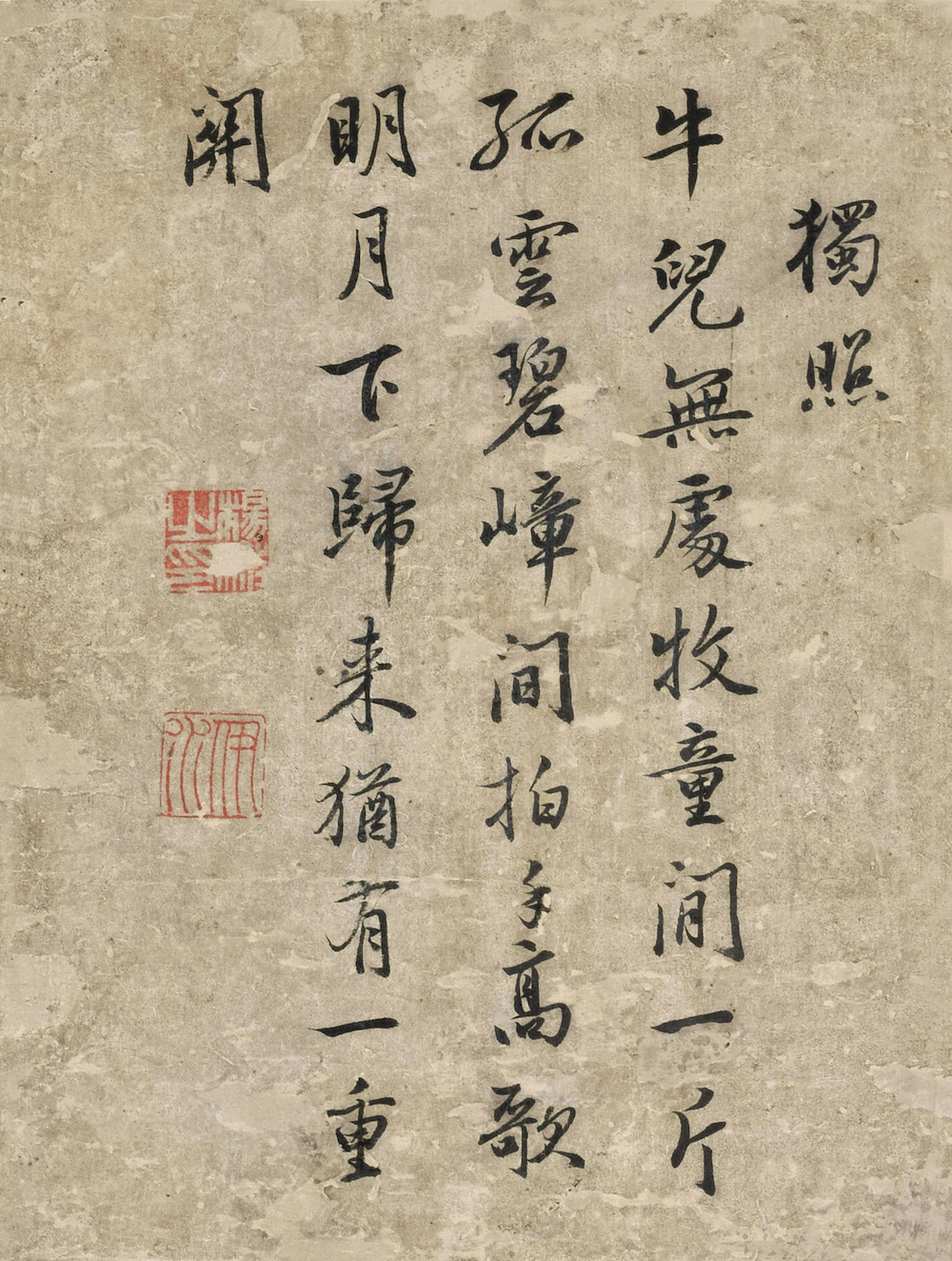

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Single-photograph on paper, coloring 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

(Ming) Zhang Mu's Cattle Atlas · Single-photograph on paper, coloring 23.7 cm long and 17.7 cm wide, donated by Mr. Yang Quan to the collection of Guangzhou Art Museum

Although Zhang Mu had a close relationship with Lingnan Zen Buddhism in the early Qing Dynasty, it did not necessarily mean that Zhang Mu fully believed in everything about Buddhism. His character, ambition and temperament made him always have the regret of being a hero in his old age and unfulfilled ambitions in his later years, so he left behind "books and swords have been hidden for a long time, doubtful and useful, and men and eyebrows often follow their desires." Sharpening the sword is still good new" and other verses. Monk Dangui, a good friend of Zhang Muduo who was paid for singing poems and inscriptions on paintings, knew Zhang Mu very well. In the fifth year of Kangxi (AD 1666), Monk Dangui wrote a preface to his collection of poems and essays "Iron Bridge Collection":Tieqiao Taoist family is near Luofu, and he reads the book of alchemy in the stone room. Once he abandons it, he gallops to test the sword, and he runs across the youth field. If he wants to use his soldiers to clear the sea, he will let himself go to poetry. The poetry and prose are very clear, and there are painters next to them. Tieqiao Yi was dirty and unwilling, so he converted to the head of the heart and pursued the purpose of no life. However, when the wine is hot and hot, there is a strong air, like a ray of electric light shining in the cold cloud and rain.

In the early Qing Dynasty, there were not only the Huashou School (Caodong School) founded by the Taoist monk, but also the Qingyun School, which was founded by the Taoqiu monk and used the Qingyun Temple in Zhaoqing as the main place for preaching. Scholars such as Chen Botao and Wang Zongyan believe that Taoism alone emphasizes world affairs and understands the truth, so it can recruit people of insight, such as natural monks, Li Suiqiu, Liang Chaozhong, etc., and convert them. Although they were outsiders, Dao Du and his disciples were loyal and patriotic. Zhang Mu converted to his disciples not only because of their religious beliefs, but also because they had a common sense of family and country. Zhang Mu was fond of Taoism in his later years. He wore a bamboo-skin crown, a cane and a cane, and a wide-sleeved shirt. He liked to talk about the art of cultivation. And Buddhist meditation is also a kind of cultivation technique, so the "good Tao in old age" here may not necessarily be just the Taoist "Tao". "Between similarity and dissimilarity" described in his "Cow Shepherd Atlas" and Buddhist classics, this may be the reflection of the subtle contradiction between his escape from the world of Zen and his unfulfilled ambitions. A reflection of deep personal awareness.

Zhang Mu's life was full of tragedies, coinciding with war and displacement, and his ambition to serve the country's merits failed to materialize. In his later years, he lived in seclusion, entertained himself with poems and paintings, and escaped from Zen and good Taoism. However, "even though the encounter is not coincidental, the reputation is immortal." He is a master painter in Guangdong in the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. His brushwork is steady, his lines are vigorous, and the horses, eagles, and oxen in his brushes are all lifelike. The flourishing printing industry in the middle and late Ming Dynasty made Zen Master Puming's "Ode to Cattle Shepherd" widely distributed throughout Lingnan and became one of the themes of his paintings. This volume of "Cattle Cattle Atlas" is an example of Zhang Mu's intersection with Lingnan Zen Buddhism in the early Qing Dynasty. Perhaps it is also an example of him seeking liberation from Buddhism in his later years, but he did not achieve "sudden enlightenment" after all. After all, the cows and shepherd boys in Zhang Mu's writings have the breath of life in the Lingnan water town, and their realm is still in the world.

(The author of this article works at the Guangzhou Art Museum. The original title is "Zen Machine in Painting: An Analysis of Zhang Mu's "Cattle Cattle Album". The full text was originally published in the 32nd issue of "Master's Gate" of the Beijing Academy of Fine Arts, when The Paper was authorized to republish it. Edited.)