"Through the Mirror of Darkness: Alchemy and the Ripley Scrolls 1400-1700," Princeton University Library, USA, shows how European alchemists built the golden age of alchemy on the basis of the Greco-Egyptian period, the Islamic world, and the late Middle Ages. Illustrations of alchemy can also be displayed as applied arts and ancient philosophical traditions.

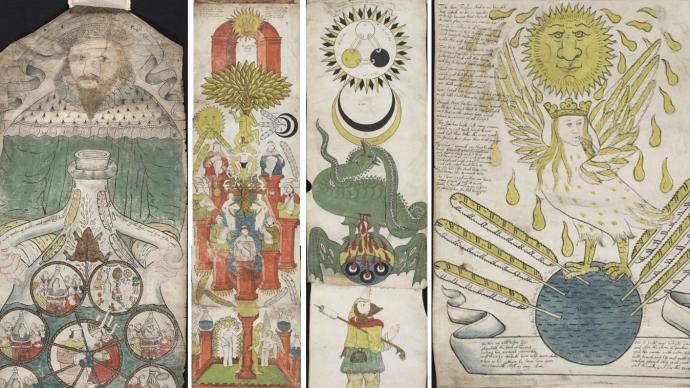

The Ripley Scrolls, 1624

In medieval Europe, alchemy was a changed science. Alchemists attempt to achieve extraordinary physical transformations: whether it's converting base metals into gold and silver, or creating elixir to prolong life. They saw alchemy as a practical artistic and philosophical tradition, and used allegorical language and obscure fantasy imagery to disguise its secrets.The Ripley Scrolls is an iconic manuscript of alchemy, produced in England in the late 15th century, probably for royal patrons, of unknown origin, later attributed to the English alchemist, The Compounds of Alchemy (1471) Author George Ripley. Over time, a new generation of readers tried to decipher the meaning of the images in the scrolls and incorporated new perspectives to reflect attitudes towards nature, experimentation and English alchemy.

The Princeton University Libraries currently hold two of the 23 volumes of the Ripley Scrolls, a manuscript that played a central role in spreading the knowledge of alchemy.

The Ripley Scrolls, circa 1590

The designer of Ripley's Scrolls should be familiar with the reading methods of various illustrated scrolls. He followed the ancient book structure represented by the Egyptian papyrus scrolls, emphasizing the continuity of illustration and text. "The makers use allegorical language and vague imagery to cover up the secrets of alchemy, the obscure, fantastical imagery that culminates in 'The Ripley Scrolls.'" Jennifer, curator of the exhibition and associate professor of history at Princeton University Jennifer Rampling said.The exhibition title, "Mirror Through Darkness" (from the New Testament), emphasizes the importance of studying alchemy more deeply through the surface; at the same time, one must refract alchemy itself through its historical practices and allegorical imagery.

exhibition site

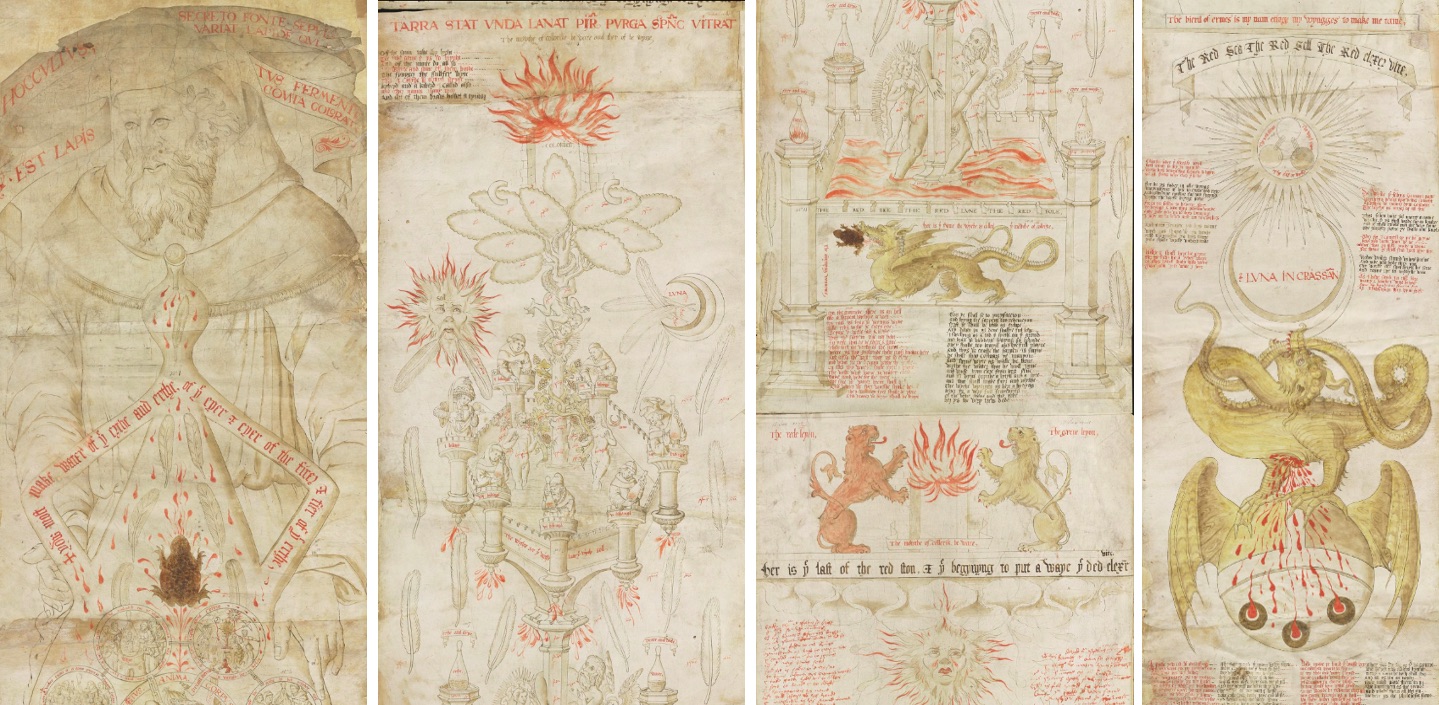

Philosopher or LiarIn the popular imagination, alchemy is often associated with quackery and fraud. The "fake alchemist" even appears as a metaphor in early satirical texts, although there is little direct evidence that the alchemist deliberately deceived. In fact, alchemists often use the metaphor in their own writings, hoping to draw a line between the learned "philosophers" and the fools who cannot decipher the secret language of alchemical texts.

In Sebastian Brant's (1458-1521) satire, The Ship of Fools (Narrenschiff, 1494), a woodcut refers to Brant's description of a fraud that he would wear a clown The hat's alchemist (left), alongside a cunning wine merchant (right), attacked a fake alchemist peddling useless knowledge.

Sebastian Brandt, inside page of Ship of Fools

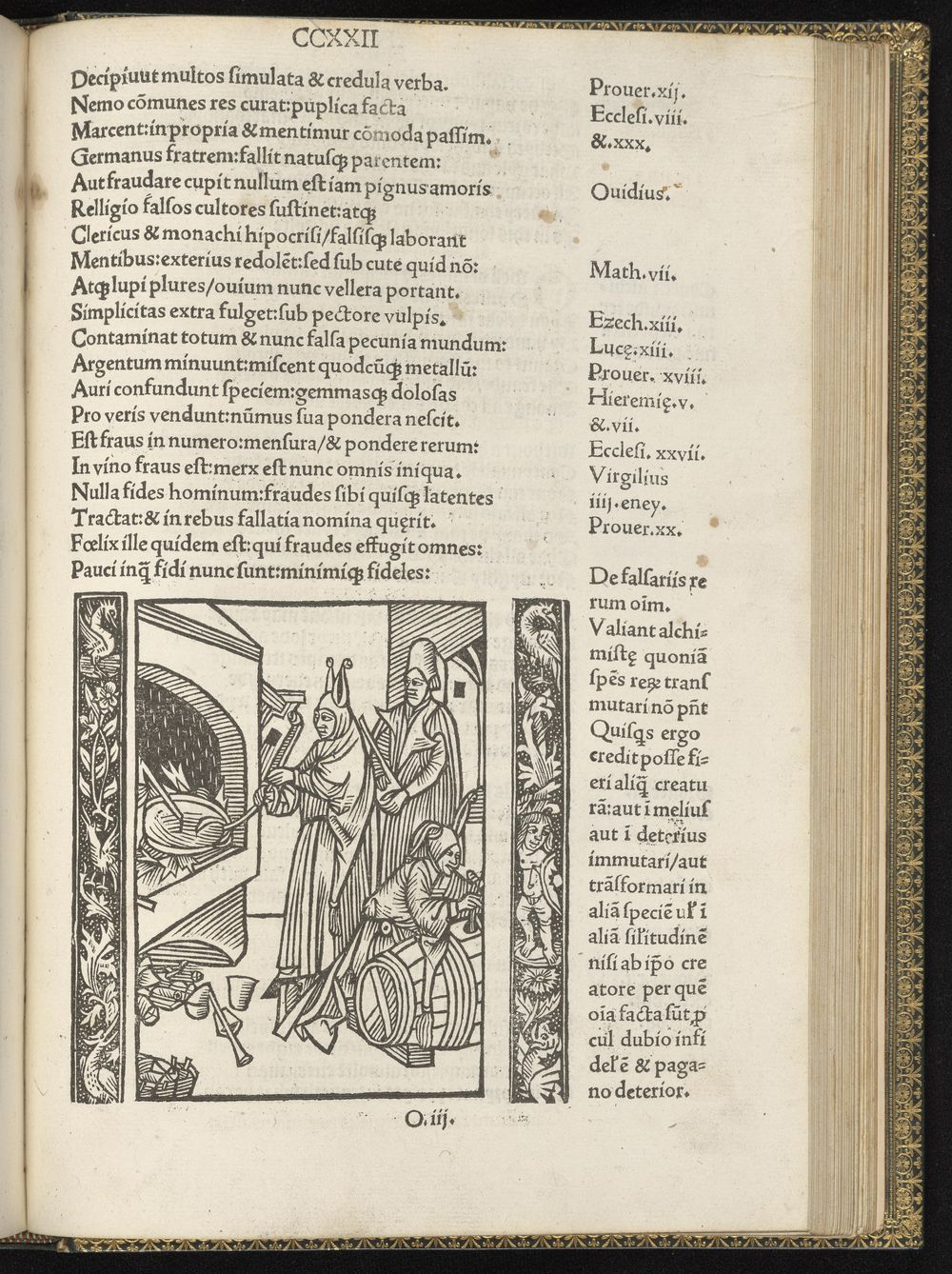

The widespread use of alchemy in 16th and 17th century England prompted playwright Ben Jonson to respond with drama. The Alchemist, premiered in 1610, portrays the alchemist as a liar (or someone who is fooled). In fact, as early as more than two centuries ago, similar characters have appeared in the works of Chaucer, the first British poet. Jonson was also well aware of the "alchemy literature" of his time, and his "The Alchemist" script cites several English poems related to alchemy, including George Ripley's "Alchemy". The Complex of '' and 'Letter to Edward IV' (1471).

Ben Jonson, The Alchemist

Master and apprenticeAlthough Western alchemy dates back to the Hellenistic period, it was still a novelty in Europe until the 12th century, with texts largely derived from Latin translations of Arabic texts, and practitioners, in order to establish prestige, positioned it as scholarship, not handicraft. To this end, they searched for authority in history, starting from the Greco-Egyptian saint Hermes Trismegistus (Greek god, who possessed treasures such as winged sandals, wands, hypnosis flutes, etc.) The seal is on their raw materials, indicating that the secret cannot be leaked) to the characters of the "Bible", alchemy, as a secret knowledge, continues in the way of master and apprentice.

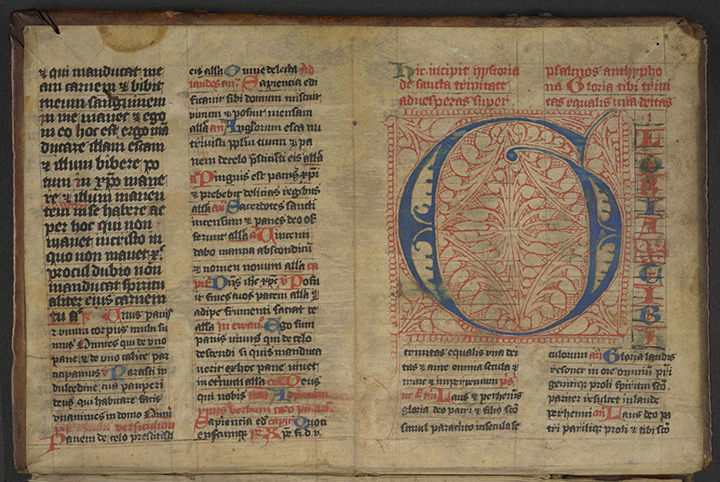

Hermes is also credited as the author of The Alchemy Corpus (also known as Hermetic Corpus), although the Alchemy Corpus was actually written in the second and third centuries, but Hermetic Moses has long been considered a contemporary of Moses, a misunderstanding that has given greater prestige to the so-called Hermes writings. The first chapter, Pimander, is presented in the form of a teacher-disciple dialogue.

A page from The Shepherd of Men, published in Paris in 1505.

In 1463, the Summa Alchemy was restored by Cosimo de' Medici, who obtained a Byzantine manuscript containing 14 articles that were written in the same year by the Florentine humanist Marr. Translated into Latin by Marsilio Ficino. Published with the help of printing in 1471.

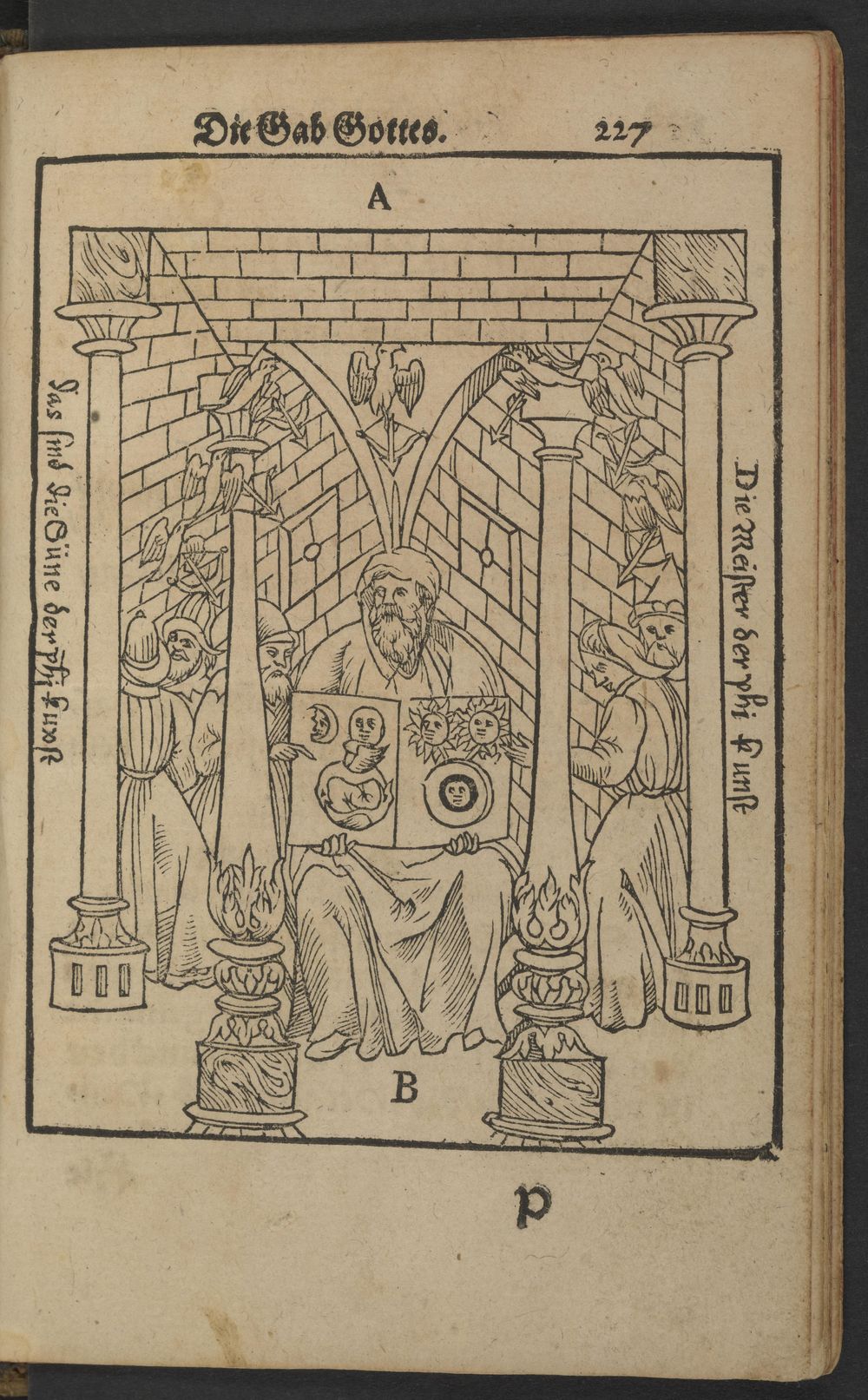

In the Name of Franciscus Epimethe, The House of Philosophy, 1582 (Basel)

In an alchemical woodcut from Germany, the statue of Hermes under the vault is represented. The old man in the painting is sitting on a throne, holding a book related to hidden wisdom. The scene is depicted several times in medieval imagery, and the book in his hand is reimagined as an illustrated book.

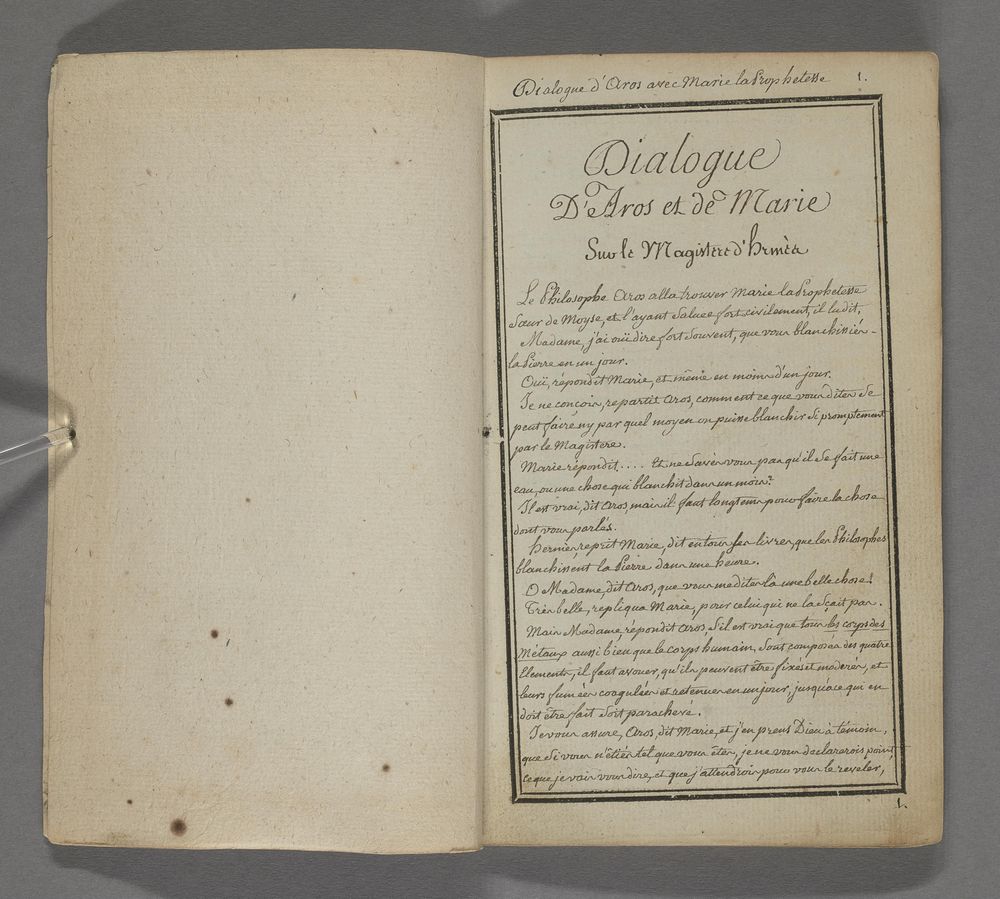

Anonymous, "Maria Dialogues with Aros", 18th century, France

Maria the Jew, one of the medieval European authorities on alchemy, used a series of cryptic analogies to teach the secrets of alchemy to her student Aros. By the 15th century, the book had been translated into Middle English poetry and copied into the Ripley Scrolls, and an 18th century French translation, possibly a translation of English poetry.

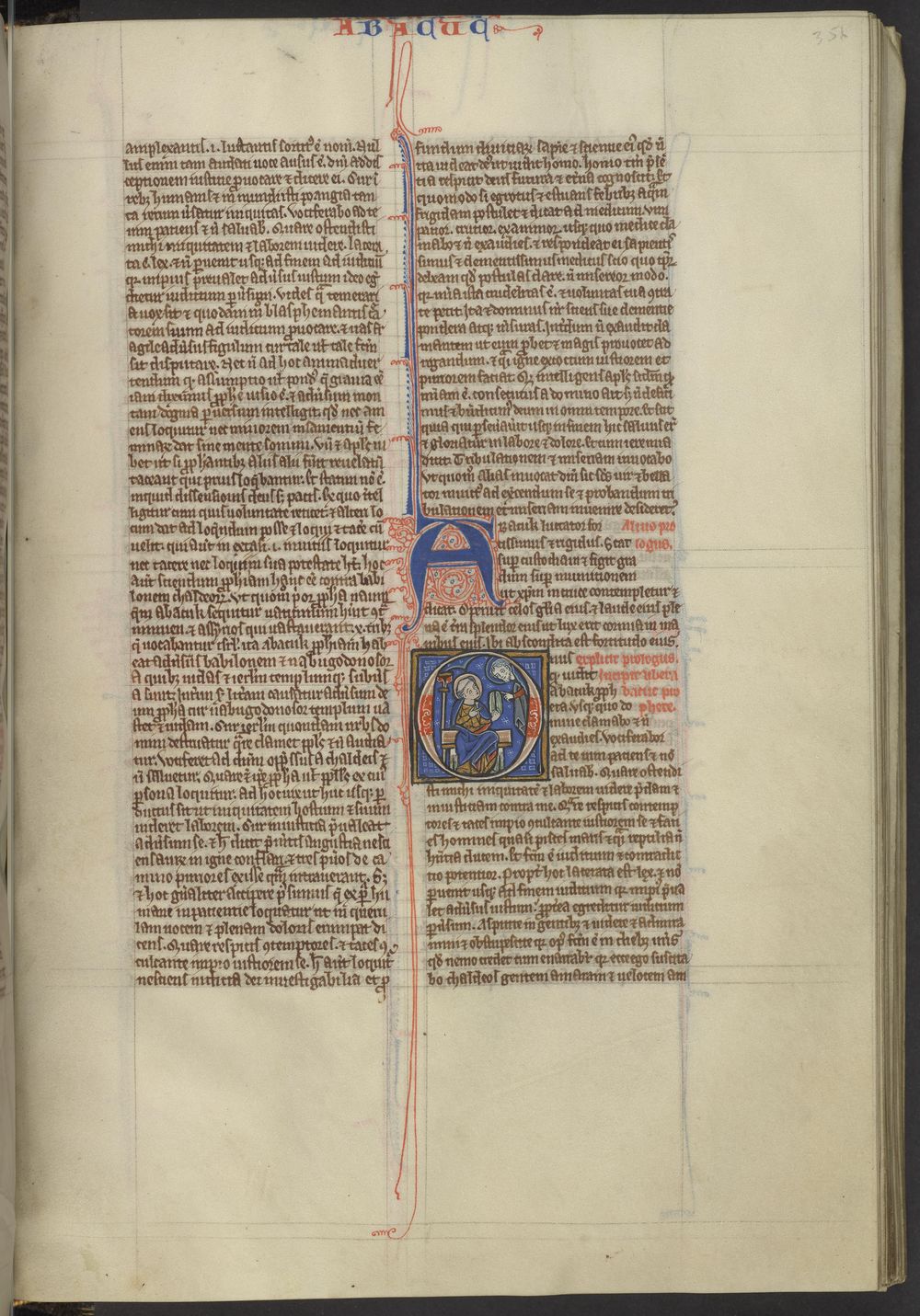

Latin Bible, England, about 1260-1270

Writers of books on alchemy often attribute success to God's grace or revelation. In religious iconography, this wisdom may have fallen from the sky and been transcribed into volumes by humans. On a page from a 13th-century Bible, illuminated capital letters show the apostle Paul seated with a scroll representing his letter to the Corinthians.Philosopher's Bottle

As a practical art, alchemy requires tools such as flasks, furnaces, and the skills to manage complex chemical experiments. The Ripley Scrolls show the practice in a glass flask called the Pelican, which is painted with toads dissolving into blood-like droplets. The name "Pelican" comes from the fact that pelicans pierce their own chests with their long beaks to feed their offspring with blood, reminiscent of religious sacrifice.

Modern reproduction, Double Pelican Flask ("gemissaries"), 1981

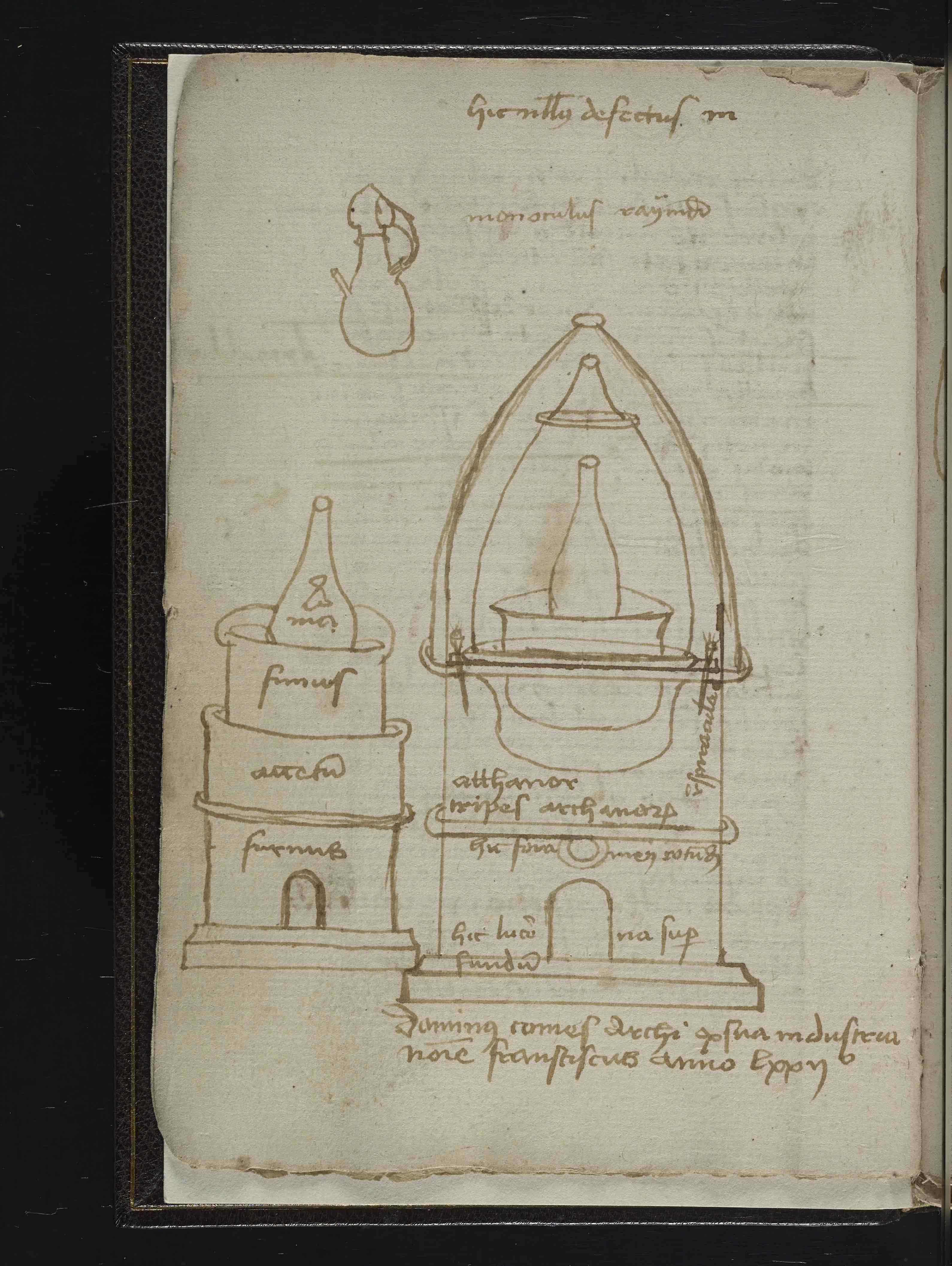

In a 15th-century drawing depicting alchemical equipment, on the left is a closed furnace, which ensures constant heat in the flask. The ingenious distillation apparatus on the right is connected to a gourd-shaped flask, which is also a "Pelican" in the Ripley Scrolls.

Name of Fake Raymond Lule (14th century), alchemical drawing (Codicillus), circa 1450-1500 (Northern Italy or Germany)

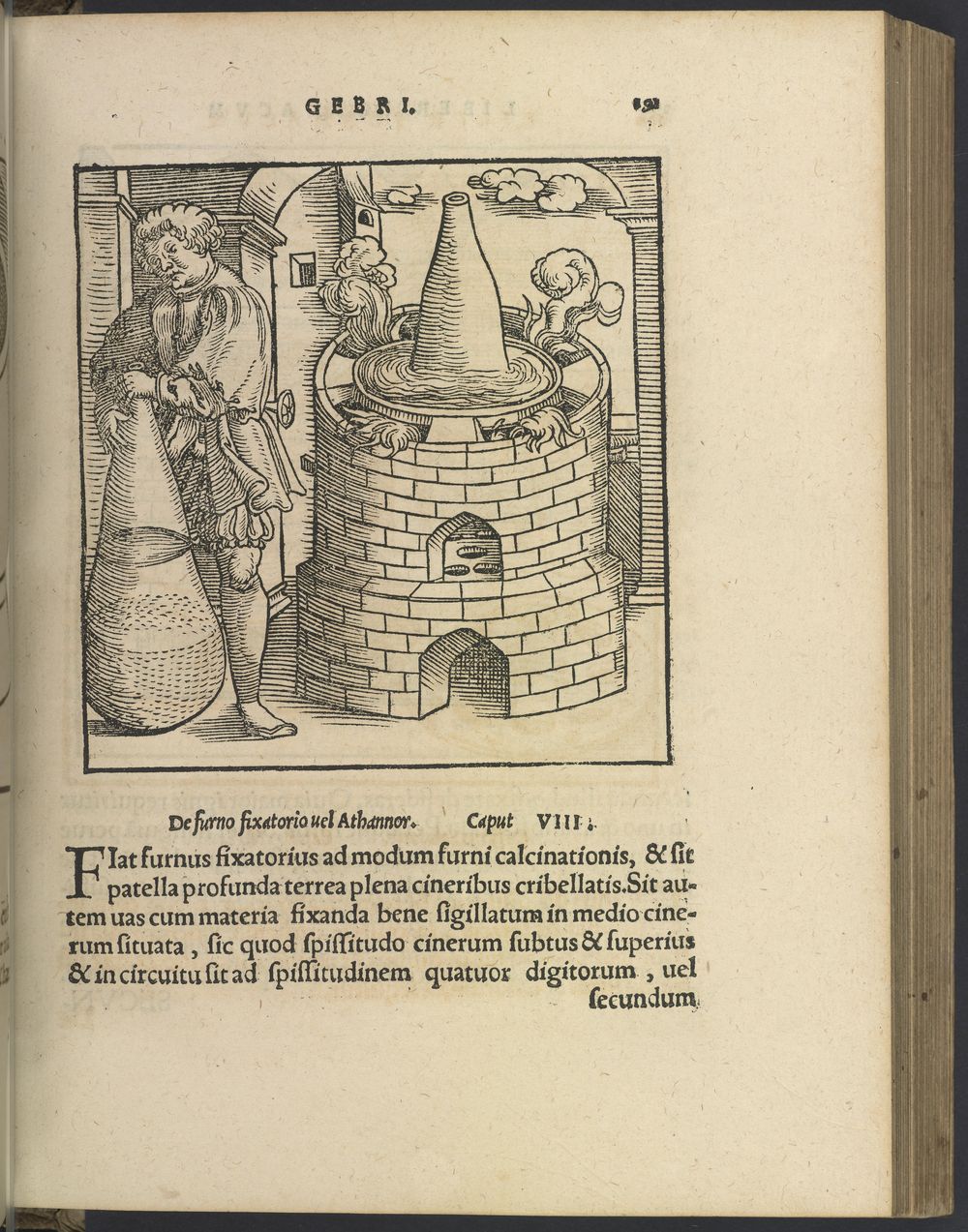

A well-constructed furnace is critical to maintaining temperatures for long periods of time. Various furnaces are described in the 13th century Book of Forges, including one with a design similar to that described in the Ripley Scrolls.

13th Century Book of the Forge

combination with chemistryThe second volume of "The Ripley Scrolls" tells the manufacturing process of the "Sage's Stone" (the Philosopher's Stone, a Western alchemy legendary prop).

The divine power of the Philosopher's Stone has been described by alchemists as divine, and there is a passage in the "Alchemy Museum": "People call the Philosopher's Stone the Philosopher's Stone, which is the oldest, the most mysterious, and the most inhospitable. What is known to man is the blessing of God, the power of morality and God, but it is secret to the ignorant."

Described by the alchemists, the Philosopher's Stone is both the chemical union of the sun and the moon, symbolizing the opposing principles of heat and dryness, cold and wetness, as well as body, soul, and spirit.

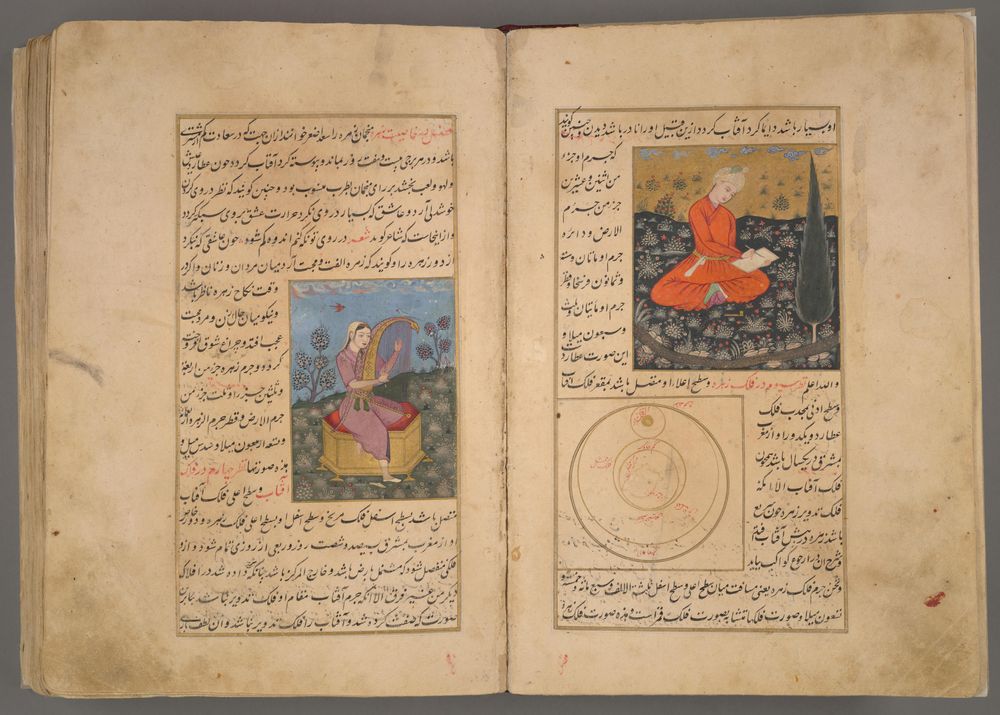

Personification of cosmic planets is common across disciplines, and the illustrated encyclopedia Miracles of Creation by astronomer al-Qazwīnī (died 1283) is widely read in the Islamic world. In the book, he depicts the planets as human figures, such as Mercury reading, Venus playing musical instruments.

Throughout the history of Islam, Muslim scholars have long debated the efficacy of alchemy. Most orthodox religious scholars oppose alchemy, while most scholars of natural sciences accept the basic idea of alchemy even though they do not believe that ordinary metals can be turned into gold. Kazvini also wrote about alchemy.

Kazvini, The Miracle of Creation, 18th century

The tradition of linking the planets to matter (gold-sun, silver-moon, mercury-mercury, copper-venus, iron-mars, tin-jupiter, lead-saturn) in the writings of alchemy and metallurgy is in the Italian painter Bekaf Woodcut embodiment of Mi (Domenico Beccafumi, 1486-1551). Under the leadership of the god of Saturn, human workers engaged in metallurgical work, and the lame gesture of the workers suggested the corrosion of lead; the liquid volatile mercury was represented as the winged messenger of Mercury.

Bekafmi, The Blacksmith, circa 1525-1540

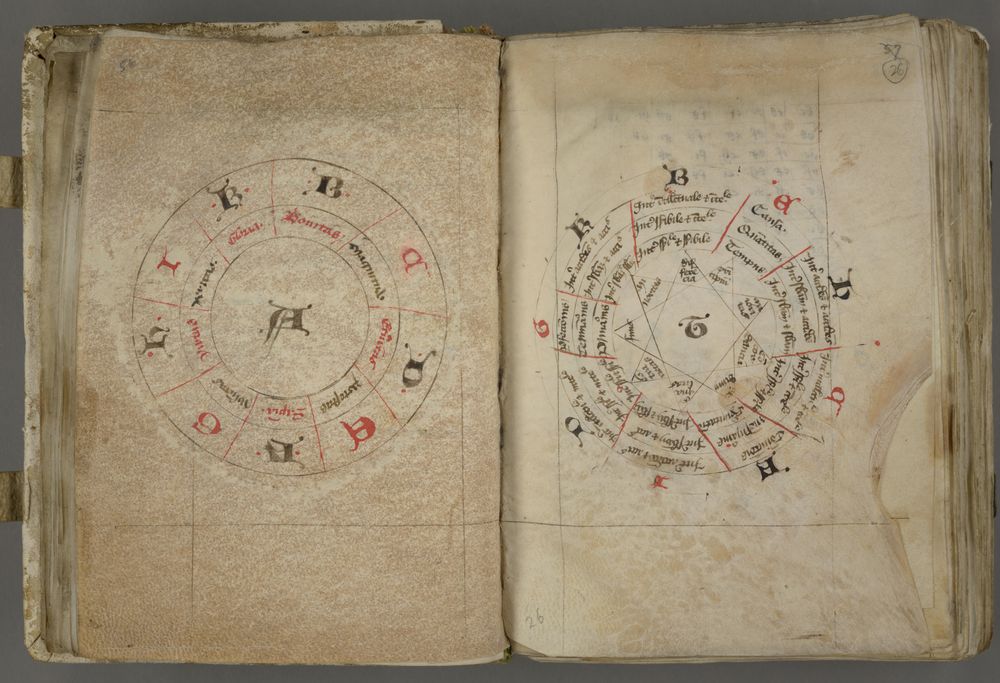

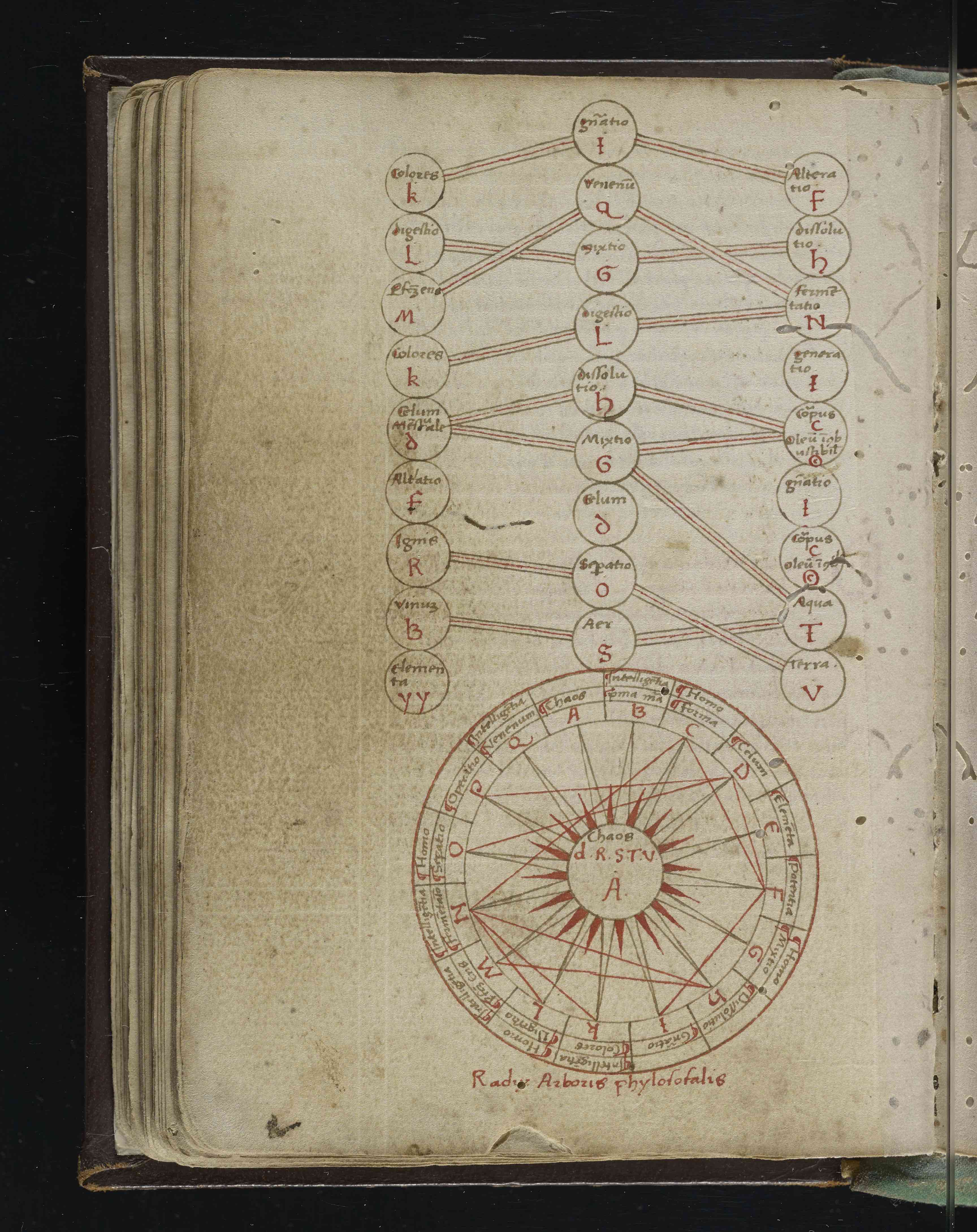

tree of philosophyThe mind map was a central device in the logical system of the Mallorcan philosopher Ramon Llull (1232–1315). This device was used by medieval Arab astrologers to calculate ideas by mechanical means. 14th-century alchemists used Raymond Luhr's diagrams to express the relationship between chemical materials and craftsmanship, and a large number of texts appeared under the name of Raymond Luhr. Although the historical Raymond Luhr did not agree with the possibility of metal transmutation, he was still hailed as the authority on European alchemy. While the Ripley Scrolls do not use mind maps, some of the images do reflect the teachings of "pseudo-lure".

Raymond Luhr, Ars Brevis (Ultimate Art), circa 1450 (England)

The writings of Raymond Luhr were widely circulated in medieval Europe. Included in a 15th-century miscellany from Oxford or Cambridge is a simplified version of Raymond Luhr's mind map (using different Arabic letters to represent different philosophical ideas. By combining numerical values associated with letters and categories, created new insights and ideas). The manuscript later belonged to Sir Henry Percy, Earl of Northumberland (1564-1632), patron of the English astronomer, mathematician and alchemist Thomas Harriet.

Under the name of Raymond Loule, The Book of the Secrets of Nature, circa 1498 (Venice)

A 15th-century manuscript preserves a "Luer-style" system of mechanical paper plates showing how mineral and organic components were combined through alchemy. Written in the second half of the 14th century, the Book of Nature's Secrets is one of the most influential treatises on alchemy in early modern Europe and an important source of the Ripley Scrolls, which record a The distilled solvent, "pseudo-lure" makes it medicinal.Provider

The final part of The Ripley Scrolls brings us face to face with the alchemists: they are not solemn philosophers, but plainly dressed figures holding pilgrims' canes, which also suggest the figure of the author of the scrolls. In some versions, he faces the flamboyantly dressed king - a clue that could be the recipient of the scroll.

Although alchemy was illegal in 15th-century England, alchemists could still seek support from the royal family. Many British rulers, including Henry VI, Edward IV, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth I, also did issue licenses and sponsored alchemy projects. The Scrolls of Ripley were often given as gifts to supporters by alchemists to arouse the royal family's curiosity about alchemy.

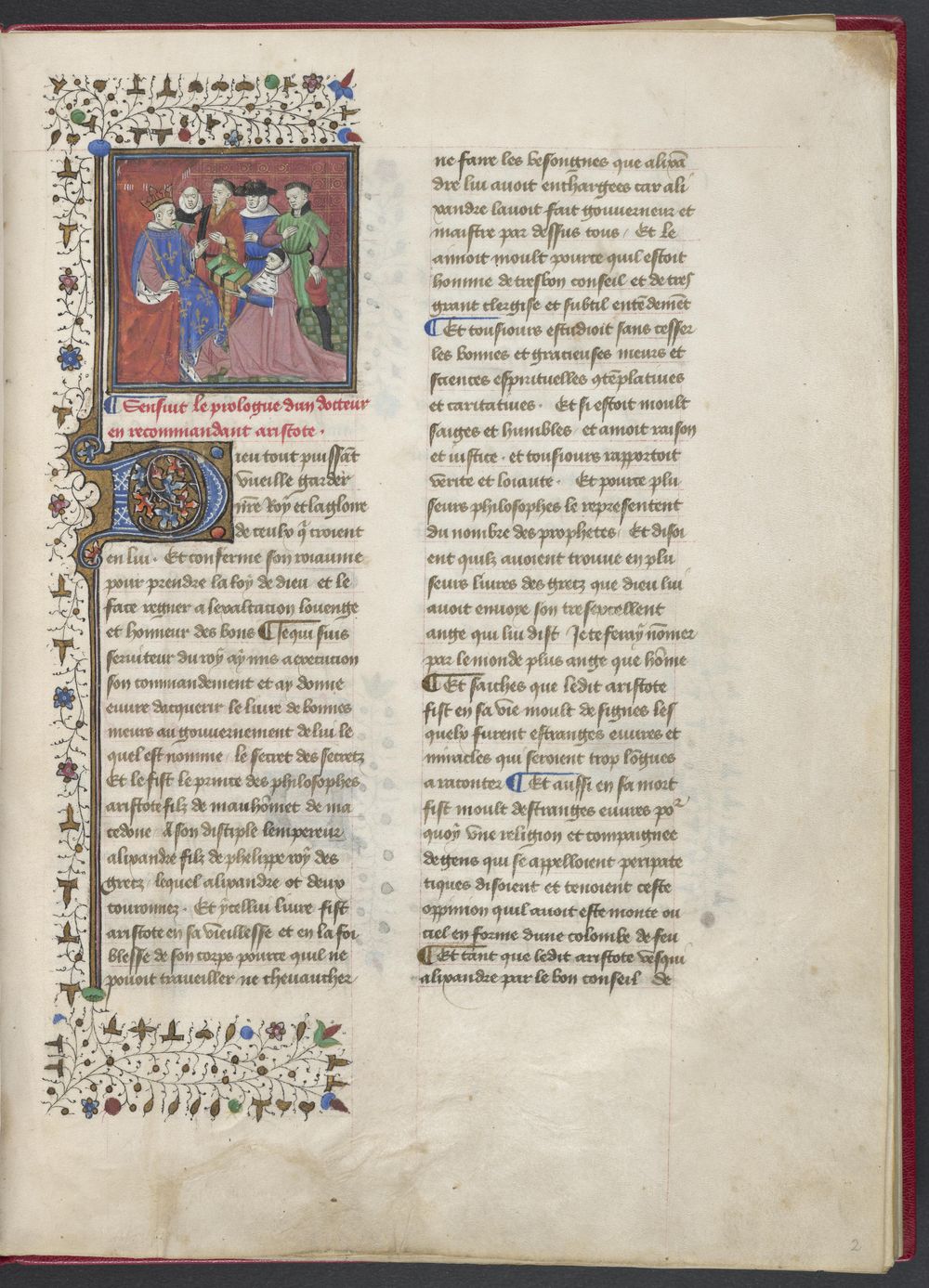

Under the name of Aristotle, The Secret within the Secret, circa 1425-1450 (Brittany)

In the Middle French version of The Secret of the Secret, a miniature shows the author (or translator) presenting a book to the king of France. In this book Aristotle advises his student Alexander the Great on topics such as alchemy and kingship. The reason why he used the name of Aristotle is to a certain extent, it is also close to the royal family's supporters.

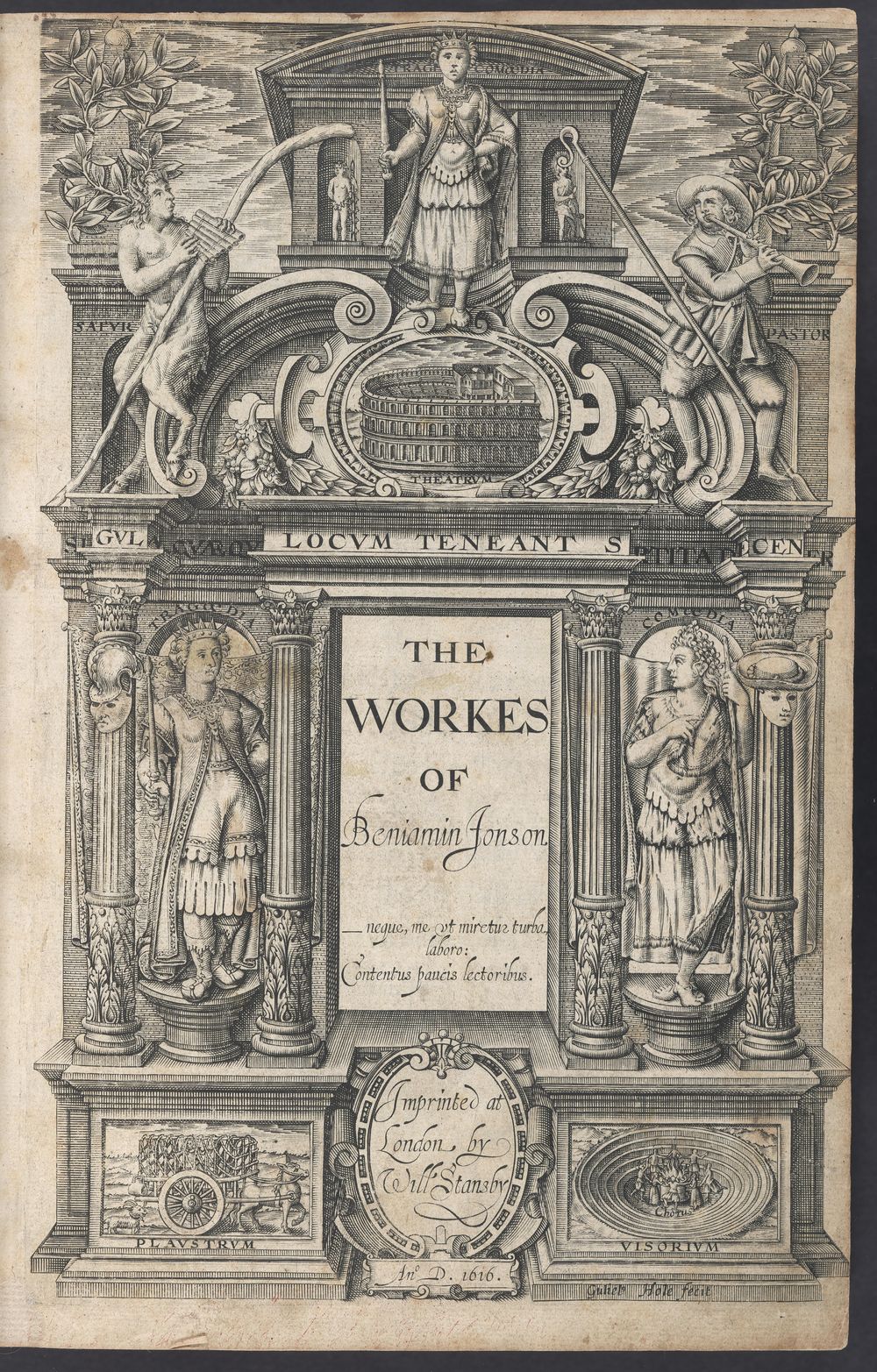

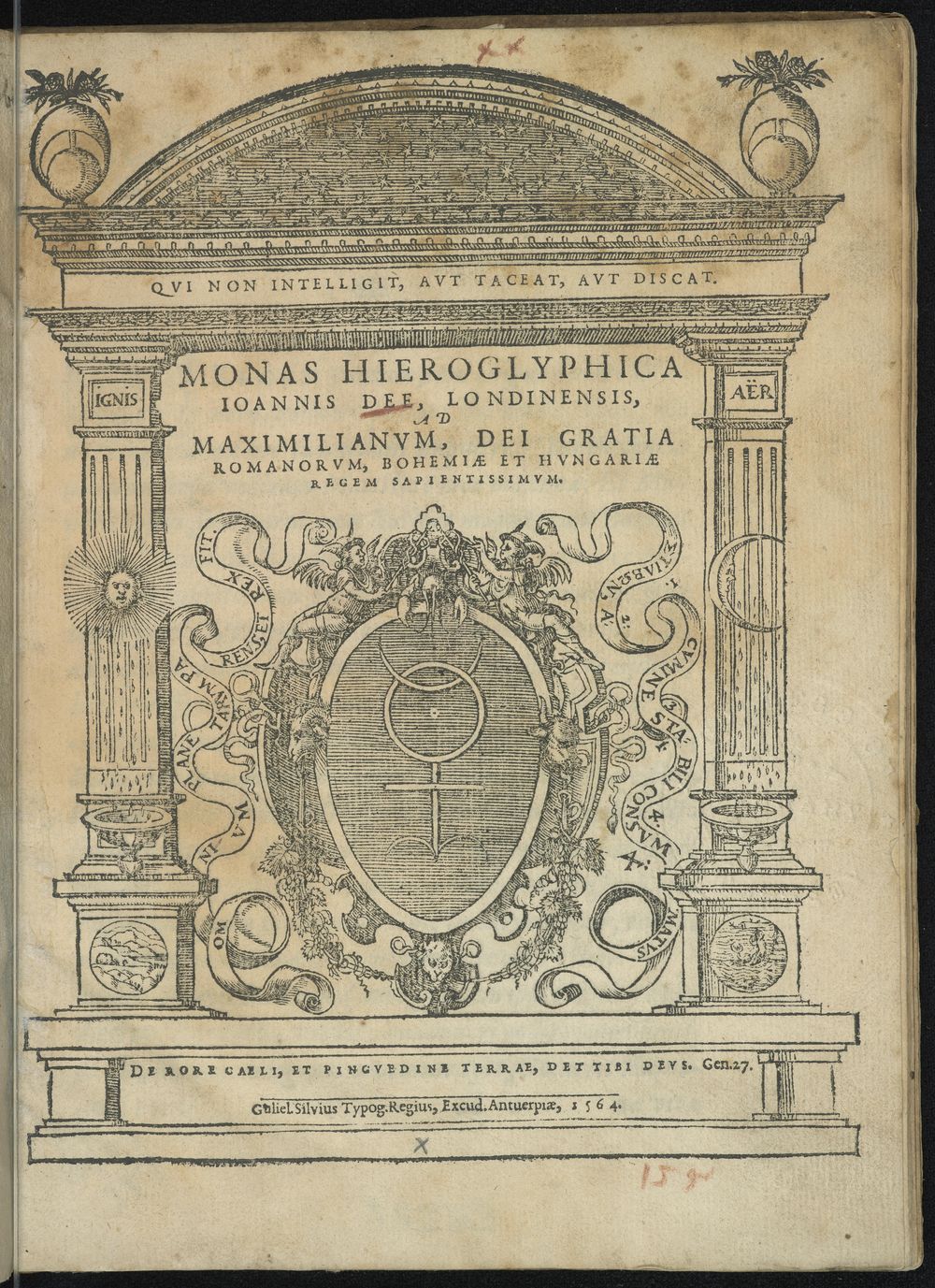

John Dee, Monas hieroglyphica, 1564

The Elizabethan mathematician and alchemist John Dee used his knowledge of alchemy to seek patronage in many parts of Europe. The only treatise he wrote on alchemy during his travels, the Monas hieroglyphica, was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II. In England, John Dee discussed the book with Queen Elizabeth I. Later, in Prague, he gave the book to Maximilian's successor, Rudolf II.depicting great work

The Ripley Scrolls represent an early attempt at alchemy in imagery, and advances in design and printing have also brought new developments to alchemy. In addition to the "instruction book"-style descriptions, 17th-century prints expressed broader relationships between art and nature, prayer and practice, heaven and earth. This progression of images is not unique to alchemy, but is used at all levels of knowledge to describe the universe and natural knowledge systems in a more vivid form.

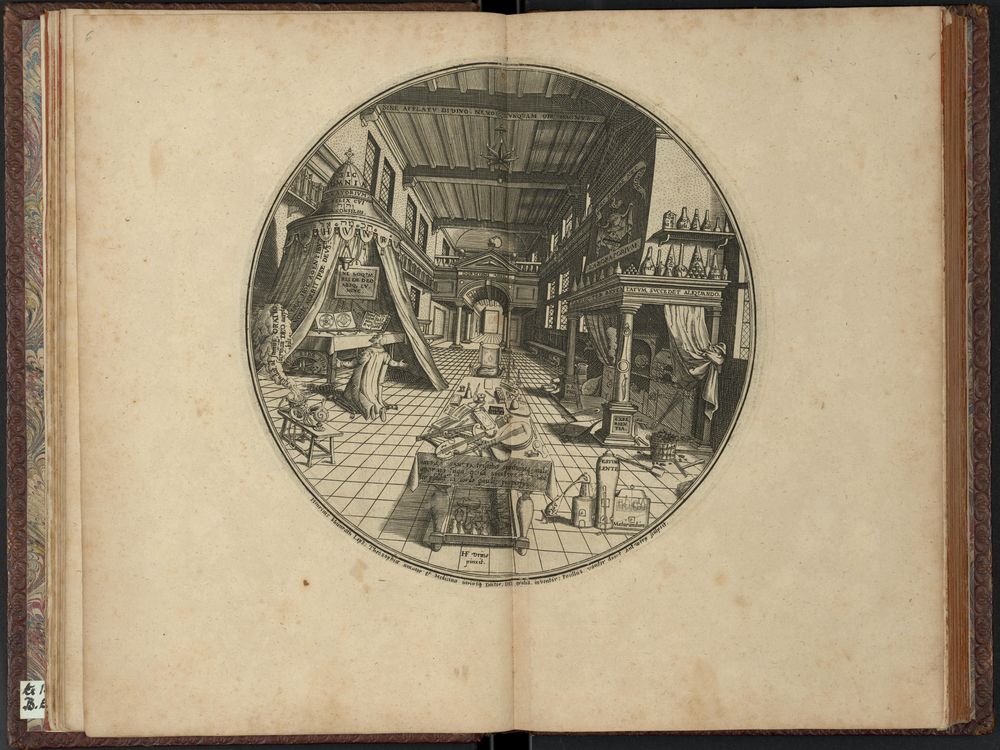

Heinrich Khunrath (1560-1605), The Fusion of the Amphitheatre, 1609 (Hanover)

Physical chemistry and divine magic fuse in the amphitheater of wisdom, written by Paracel physician and alchemist Heinrich Kunlath. The relationship between the sacred, the supernatural and the natural realms is reflected in a series of delicate circular prints - most notably the etchings of Khunrath's "laboratory", where an alchemist can be seen on the left Prayer, that is God's realm; on the right is a fully equipped laboratory that represents the realm of nature.

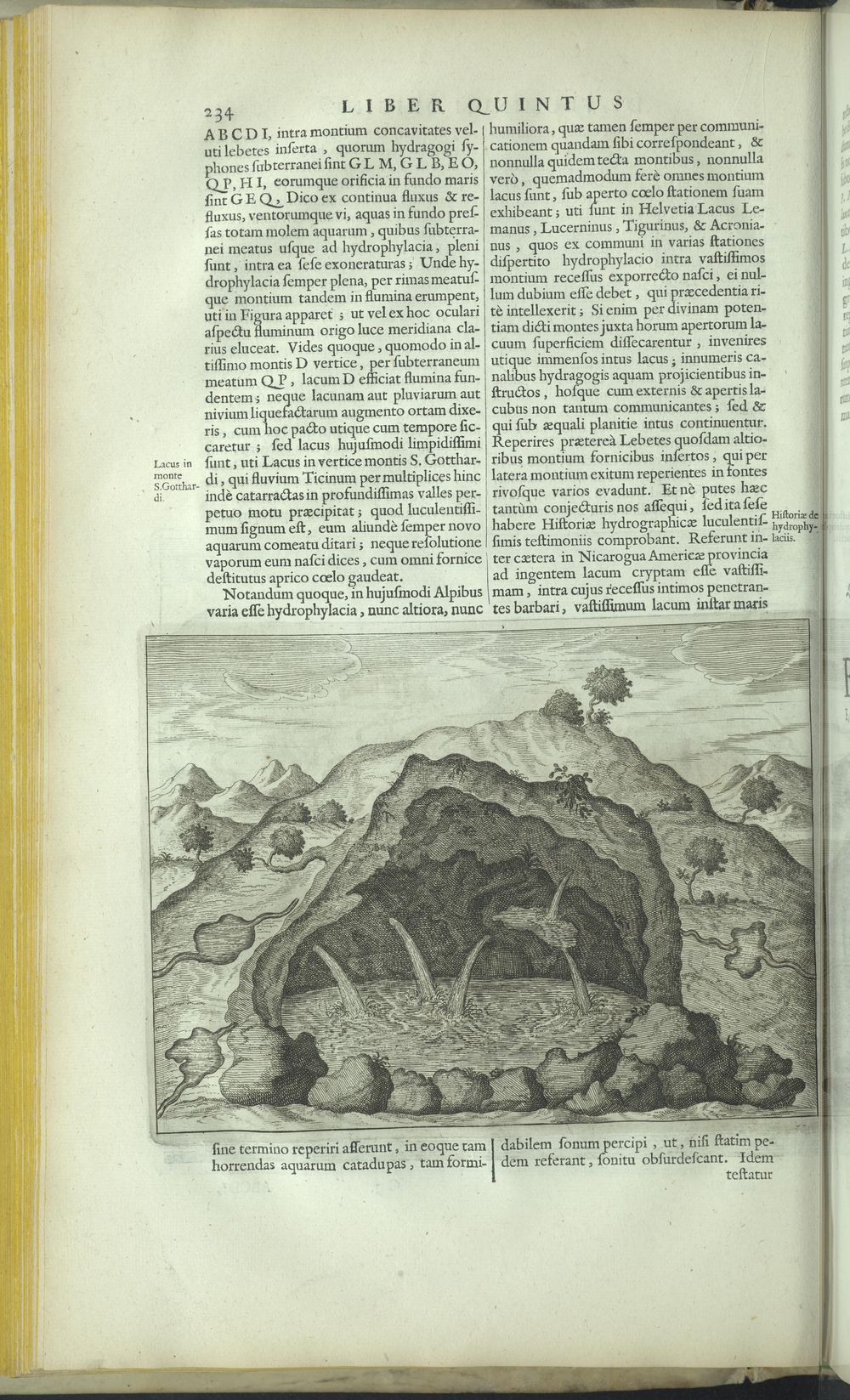

Kochet, The Underworld, 1655 (Amsterdam)

In 1638, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher gazed at the crater of Mount Vesuvius. Years later, in Underworld, he envisioned a network of fiery subterranean reservoirs that fueled volcanic eruptions. Based on medieval theories, he proposed that volcanic heat formed "sulfur" and "mercury," which, through a process similar to fractionation, formed different metals and minerals.

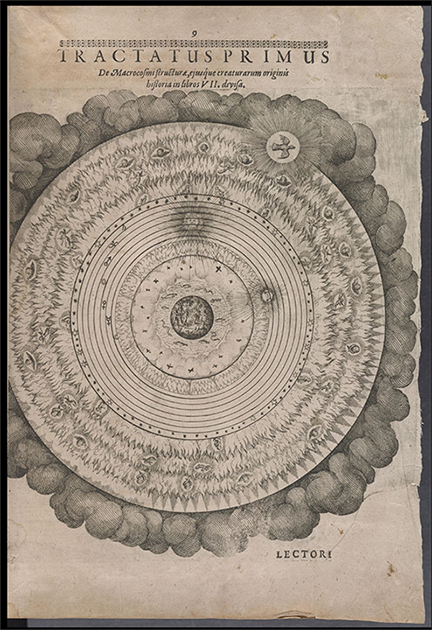

Robert Freud (1574-1637), History of the Microscopic World, Volume 1, 1617 (Oppenheim, Germany)

Throughout the two volumes of "History of the Big World" and "History of the Micro World", doctor Robert Freud used exquisite geometric diagrams to explore the correspondence between the big world (the universe) and the small world (human beings). His cosmology draws on the philosophy of Neoplatonism and the writings of Paracelsus and envisions it as a chemical separation on a cosmic scale.

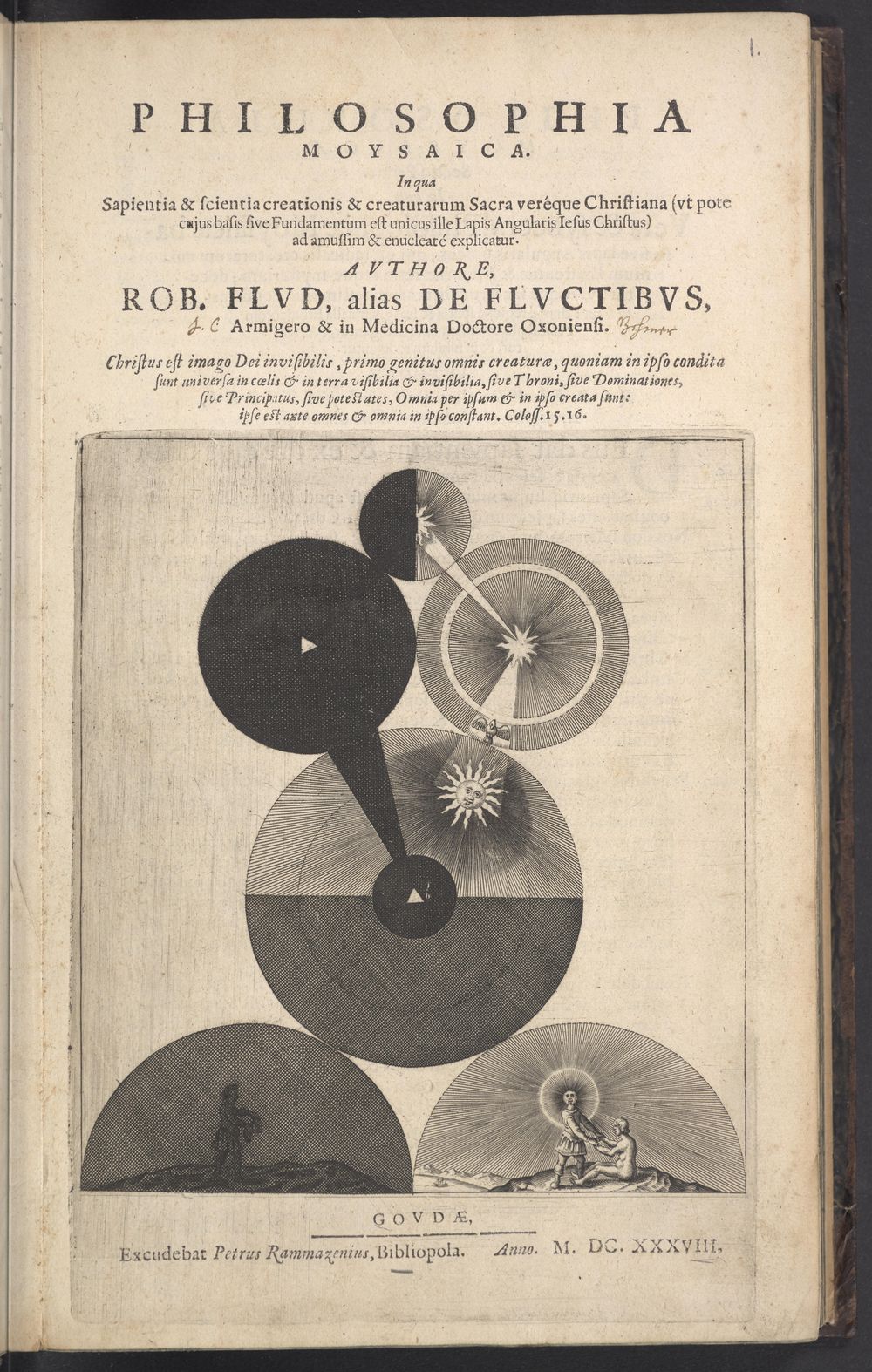

Robert Freud, The Convergence of Philosophy, 1638 (Netherlands)

Freud also used circles to express complex metaphysical relationships. Different circles represent different meanings of God, the world, etc., and now it seems to have the shadow of modern art.

exhibition site

Refining gold was the main goal of European alchemy, which modern science has proven impossible because gold is a metal element with atomic number 79, not a compound. However, since the 12th century, the Arabic and Greek alchemical texts translated by the Western world and the large number of experiments accompanying them have accumulated experience in chemical experiments, invented various experimental instruments, and learned many natural minerals. The images of alchemy also have artistic value.The exhibition will last until July 17. This article is compiled from the website of the Princeton University Library.